It doesn’t matter how many times I see this poster, every single time I see it I think “What the hell is Elvis Costello doing in a movie with Tom Hanks and Julia Roberts? And why is he wearing that mustache?!”

Movie Night With Urbaniak: Heaven’s Gate (part 2)

“So. Now I can say I’ve seen Heaven’s Gate,” quoth

as the credits roll.

Which is about all there is to say. I have no profound insights to add to viewing the second half of Michael Cimino’s legendary disaster. (You may read my comments on Part I here.)

The second half moves a good deal more quickly than the first, largely because its narrative is substantially more compressed, but it is no more dramatically coherent. There’s very little sense of “this happened, then this happened, and because of that, this happened” — it’s more like a series of discrete events presented in pageant form with very little to connect them dramatically. Some of the staging of these events is thoughtful and impressive, and some is not. But more importantly, not enough of it has any dramatic weight.

Kris Kristofferson is the sheriff (or not — it’s unclear). He’s in love with a prostitute, who’s in love with an assassin, whose job it is to kill her. Good setup. A little melodramatic, but eminently workable. What happens in this fraught tangle of misspent love? Well, the prostitute gets raped by some cattlemen, which makes the assassin switch sides, which makes the cattlemen put their invasion on hold to go after the renegade assassin. That’s right, three hours into the movie, the cattlemen put their invasion on hold to go after a renegade assassin. The leader of the cattlemen has set the narrative into motion by forming this army of gunmen, and now, three hours later, now that the time has come for him to put his army of gunmen into action, he says “Well, wait a minute, hold your horses, what about that renegade assassin?

Has the assassin vowed to lead the immigrants in an armed resistance? No. Has he personally sworn to kill the leader of the cattlemen? No. With history and three hours of squandered narrative bearing down on him, the leader of the cattlemen decides to take a little detour on his way to destiny. The assassin and some other guys who happen to be in the cabin at the time are killed by the cattlemen. So, faced with an interesting dramatic problem regarding an unsolvable lover’s knot, the writer/director chooses to ignore his romantic plot altogether and have the characters go do something else. (For the record, the prostitute says good-bye to the sheriff and rides to be with the assassin, happens upon the shooting, barely escapes with her life, then races to town with the news of the imminent invasion — oh wait, no, that’s not what happens, no, she races to town and finds that the town already knows about the imminent invasion. Which means she didn’t have to race to town after all, because the shouting immigrants already have a plan. Let’s face it, three and a half hours into the movie, the main characters all kind of kick back and relax while a bunch of people we’ve never met before get on with blowing the shit out of each other.

Kristofferson is given the classic Western moment of the gunman who, brokenhearted, turns his back on the problem at hand and fixes to light out for the territories. Except he doesn’t. He says he’s fixin’ to, but instead he hangs around town. Then, later, unannounced and without preamble, he wanders back into the narrative and is suddenly seen acting as the leader of the immigrant forces, giving them ace military tips that, er, that get lots of immigrants massacred (okay, maybe those tips weren’t so ace after all). As I say, each of these events is presented as an individual event seemingly unconnected to anything that has happened before or since.

John Hurt, bless his heart, fares worst. He doesn’t even seem to know what he’s doing there. He drinks, he looks guilty, he barks out this or that exhortation, then dies unceremoniously in a shootout. He dominated the first 23 minutes of the movie (the scenes at Harvard) and he’s supposed to be the protagonist’s best friend, but his character and death are rendered meaningless.

As with the first half, much of the photography is stunningly beautiful, or would be if the transfer were any good, which it is, alas, not.

Kids these days

(The TV room, afternoon. Kit (4) is watching The Fairly Oddparents. A commercial is playing.)

KIT: Stupid remote! Stupid! Dad! Da–ad!

(Dad enters.)

DAD: What’s up?

KIT: I can’t get the remote to work!

DAD: Let me see it.

(He takes the remote. It works fine.)

DAD: It works fine.

KIT: I mean it won’t work on this TV show! I can’t get it to start over, or skip the commercials, or pause when I need the bathroom!

DAD: Oh, well that’s because this is live TV. Here, see, when you press the “pause” button, the little box comes on in the corner that says “LIVE TV?” That’s what that means, it means that this is being broadcast right now, it’s not a recording, you can’t pause it or make it go back.

KIT: Grrrrrrrrrrrrrrr! I HATE LIVE TV!

I am pleased to announce…

…that for the first time in my experience, I was forced to cut down my votes for Best Screenplay to ten. In the past, I’ve always had to strain to find five original screenplays and five adapted screenplays worthy of nomination, often voting for the works of friends or writers I admire, even when I thought the actual script wasn’t very good. But this year I actually had to go through the list twice and painfully un-check three or four scripts from each category I would have gladly voted for in order to limit my votes to five apiece.

Naturally, I was limited to movies I have already seen. Sorry, Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem. Next time send a screener.

Republicans have been getting a lot of stick lately for their so-called crimes. I mean, sure, they steal elections, gut the constitution they were sworn to uphold, start costly, unnecessary wars that throw nations into tumult, squander our nation’s reputation and kill hundreds of thousands of people in order to enrich themselves, loot the treasury, place bonehead incompetents in high positions of power and influence, shoot men in the face then demand they apologize, cackle at the destruction of American cities, flout the Geneva Convention, politicize religion, children and anything else they think will benefit them, hypocritically pass anti-gay legislation while acting as closet gays, disregard the Bill of Rights in order to erode whatever civil liberties they think will gain them more power, but at least no one can say that a Republican would torture a stray dog, hang it by its neck over a tree limb, slit its throat and then stone it to death.

What’s that you say?

Shocker headline: Garfield made funny!

Some people have discovered a method for doing what has been thought to be impossible fordecades: making Garfield funny. It involves an ingenious, apparently foolproof method of simply removing all of Garfield’s thought balloons.

It’s kind of amazing how well this works. It takes a strip that has always been flat, tasteless and embarrassing and fills it with tension, sadness and mordant humor. It’s easy, fun and much less time-consuming than placing the panels in a random order.

Okay, God, let’s have it out. You and me.

I gotta say, you’ve done some pretty weird shit in your life, but there are limits, okay? Katrina, I can’t figure that one out — what was the point of that? And then the Southern California wildfires. And the tsunami. And the droughts.

I get it, I get it — you work in mysterious ways. I’ve been paying attention, I get it.

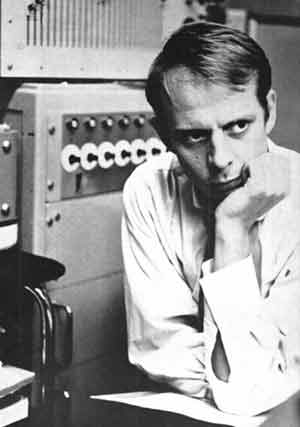

But, please, give me a clue. Help me understand. Why on Earth, in the course of five billion years of our planet’s existence, would you possibly need to take Karlheinz Stockhausen, Ike Turner and — gasp — Dan Fogelberg all in the same week?

Let me try to parse this latest act of bizarreness. You’re up in Heaven, and you say “Hey, you know what we need up here? Some dense, impenetrable German avant-garde music!” So you call Karlheinz and he shows up and you hear the kind of stuff he does and you say “Okay, okay, it’s good, but you know what it needs? It needs a beat, you can’t dance to this stuff, who really knows how to turn a beat down there?” And so you grab Ike Turner and you put these two sounds together. It sounds like it would be super-ugly to me, but what do I know, maybe the clash of high German weirdness and deep American grooves sounded great, but the only thing I can think is that it sounded a little, you know, heavy, what with the postwar anomie and the wife-beating and all that.

That’s the only justification I can see for adding wimpy folk-rocker Dan Freaking Fogelberg to the mix. Have you even heard this guy before? Can you even begin to imagine the world of pain your ears are in for, trying to weld together Stockhausen, Turner and Fogelberg?

And who’s going to be next? Christ, who’s going to have to show up to this jam session to meld together all these sounds? Bassist from Ratt? Yma Sumac? Ornette Coleman?

Star Wars Episode VII

Produced, written and directed by Sam Alcott (6). Edited by Todd Alcott. Performers: Sam Alcott and Todd Alcott.

This movie was created under the strict supervision of Sam. The shot list, scene order and camera placement were all his (with occasional input from me). When you hear me say a line of dialog, I am saying only and exactly what Sam has directed me to say. (In certain cases we had to do several takes of a scene because my voice was not right or I improvised too much with Sam’s dialog.) It was shot entirely on a Sony Cybershot, a digital camera designed to take still photos and short movies.

Sam has picked up the lingo of moviemakingvery quickly. He will ask if we’re rolling and understands the commands “Action,” “Cut” and “Pull back,” and soon I’m sure will be saying things like “Okay, now I want a steady tracking shot along this way, then push in close to here, then we’ll cut to a close-up of the girl’s face reacting.” He has an innate, if incomplete, understanding of cutting techniques and carries the whole movie inside his head. On occasions when I left out a scene I thought was confusing or dragged the narrative, he would see the gap immediately and instruct me to put it back in. As a result, I felt it would be best to insert some titles to help explain the action, which might not be immediately apparent to non-aficionados.

PLOT SYNOPSIS: General Grievous is planning some kind of attack on Kashyyyk. The Clone Army arrive and foil his plans. Grievous sends his troops to fight the clones but they fail (these scenes were not shot). Grievous then attacks the Jedi himself, killing several of them. The Clones then receive “Order 66” from Darth Sidious, which causes them to attack the Jedi. Yoda and Obi-Wan fight the Clones, and Obi-Wan kills General Grievous and wipes out the remainder of his forces. Then, for reasons that elude me, the ending of Episode III is recapitulated.

(I am being disingenuous — I know why the ending of Episode III is recapitulated — it’s Sam’s favorite part of the whole Star Wars saga, specifically the fight between Obi-Wan and Anakin on Mustafar. The mining apparatus and volcanic surface of Mustafar are here represented by a credenza, a chair and a Disney Princess scooter (belonging to Sam’s little sister).

Sam was disappointed with the final cut only because he hadn’t thought his hands would be so visible in the shot. In his mind, the characters moved and acted the way they do in the movies. He instructed me to digitally remove his hands and body from the shots. When I explained that that is possible but cost-prohibitive, he said “But we could scan the movie into Photoshop and erase all the parts we don’t want.” When I told him that that would involve working on literally thousands of individual still frames, he relented. But I think the boy has a future.

Coen Bros: O Brother, Where Art Thou?

I clearly remember seeing this movie for the first time. I was in Paris with

and our wives and we were all very excited to see the new Coen Bros movie before it opened in the US. Before the title sequence even began, I knew that I was watching a singular work of genius.

And there in my seat in the small, boxy Paris theater (it was, literally, the last day of the movie’s run in France) I thought “You know what would be a good idea for a movie? A movie that shows the evolution of American music, beginning with its roots in slavery, showing how it springs from both broad sociological movements, yes, but also ties it to the specific rhythms of the everyday activities of the people performing it.” And then the movie began and I realized I am watching that movie right now.

(If you’ve never done it, it’s a real treat to watch an American movie, especially a comedy, with a foreign audience. They laugh at the jokes a few seconds before you do because they read the subtitles faster than the actors can speak.)

O Brother, Where Art Thou stands as the Coen Bros warmest, most expansive, most generous, most delightful, most optimistic movie. That it does all those things without having a proper plot is something of a miracle.

THE LITTLE MAN: Ulysses Everett McGill and his compadres (seemingly the only three white people in prison in Mississippi, who all happen to be chained together), like many Coen protagonists, seek a treasure, the suitcase full of money that will transform their lives and make them worth living. As with most Coen movies, the search for, control over and lack of money is the driving force of the narrative.

Now look at where that money comes from. According to Ulysses, the treasure was stolen in an armored car heist. That would make the money the possession of “the bank,” an institution that lost favor in Depression America for foreclosing on mortgages (which gave a bank robber like Baby-face Nelson heroic status, despite being a certifiable pyschopath). So Ulysses is a criminal, uniting with two other criminals to pursue money gotten in a crime, which was in turn gotten by banks in the act of what was widely perceived as another crime. Ulysses and his pals don’t find their treasure (because, of course, there is no treasure) but they do find success as recording artists, getting paid $60 to sing a song, which the record company then turns into unnamed profits, in yet another kind of criminal scheme. This all ends up benefiting Capital, in O Brother symbolized by biscuit magnate and corrupt governor Pappy O’Daniel, who hands out patronage and represents Politics As Usual.

So there is plenty of money flowing through the narrative of O Brother, and all of it is achieved through ill-gotten gain. Money flutters through the air around George Nelson’s car, gotten as easily as walking into a bank and taking it, lost as easily as running into a crooked Bible salesman. Everything is a con, Ulysses is a fake (as opposed to his “bona fide” romantic rival), everyone is trying to make a dishonest buck. God is a racket, music is a racket, even sex is used as a trick to turn a man in for the bounty on his head. The “real people” of O Brother, the farmers and clerks and store customers, the churchgoers and voters, are seen by all the main characters as rubes, sheep and marks.

(Money is not the only thing that flutters through the frame in O Brother. A number of butterflies also happen by, usually in scenes associated with Delmar. I take this to mean that money, as it is in Lebowski, is an abstract commodity that happens by by sheer chance, or else that Delmar is like a butterfly.)

(And then there are the cows. The Coens go to a lot of trouble and expense to mistreat cows in one scene [“I hate cows!” shouts George Nelson, apropos of nothing], and then place a cow on top of a building at the climax as proof of the Magic Negro’s prophecy. I’m not sure what the cows are all about.)

There’s a moment in Act I when Ulysses and his pals go into the recording studio to sing “Man of Constant Sorrow,” a stunning piece of music direction all by itself, but George Clooney’s doing something interesting in the scene. As Tommy plays his guitar and Delmar and Pete sincerely belt out their harmonies, Ulysses looks, of all things, worried. This always puzzled me until I realized that he’s worried about getting caught in yet another criminal activity — it doesn’t seem possible that “singing into a can” could be seen as a legitimate way to make a living.

(The notion of “artist as outlaw” is one that the Coens share with their fellow Minnesotan Bob Dylan [who provides The Dude’s theme song in Lebowski], a connection I will explore more in my thoughts on The Man Who Wasn’t There.)

(But while I’m here, of course there is a more explicit Dylan reference in O Brother with the Coens’ use of “old-timey music,” which was enjoying its first revival in the Depression-era South, and then had a second revival in the late fifties in the North. Bob Dylan recorded the song that Ulysses sings, “Man of Constant Sorrow,” on his first LP.)

(Wash Hogwallop refers to the O Brother‘s economy by saying “They got this Depression on,” a line which has always sounded telling to me. Wash doesn’t see the Depression as the result of any confluence of economic events, he sees it as a a deliberate choice made by powerful people in faraway places, as though one would throw a Depression the way one would throw a garden party, as though it was a deliberate trick played on the poor, uneducated people of the South. Which I’m sure is how it felt.)

MUSIC: Music, we find, transcends the criminal world in O Brother, and is the thing that lifts the narrative from the commercial to the spiritual. As in most Coen movies, there are two major strands of music at war with each other — in this case, “black” music (blues and spirituals) and “white” music (folk and gospel). Instead of symbolizing the conflicts of the main characters as it does in most Coen movies, music here becomes subject matter itself. O Brother, in the course of its Three-Stooges narrative, chronicles a moment in American musical history where black music and white music fused, through the secular miracle of mass communications. Radio in the ’30s was like MTV in the ’80s — it brought all kinds of music into all kinds of worlds that had never heard it before, and musical cross-pollination in O Brother almost single-handedly transforms The Old South into The New South.

(Sam Phillips said in the ’50s that if he could find a white singer with the negro sound and the negro feel, he could revolutionize music. O Brother turns this formulation on its head, having its trio of white singers [who actually are seen in blackface for one sequence] be confused for black singers singing white music — a notion that shocks and enrages the racists of The Old South but delights the enlightened souls of The New South.)

CRIME AND PUNISHMENT: Surprisingly, O Brother presents the Coens’ darkest view yet of law enforcement. Police are absent in Blood Simple, comic bunglers in Raising Arizona, corrupt in Miller’s Crossing and menacing in Barton Fink, but O Brother goes so far as to paint them as literally evil, and the sheriff in charge of tracking Ulysses is no less than the Devil himself.

Thismakes tracking the spiritual signifiers of O Brother easy as pie. If Sheriff Cooley is the Devil and damnation, and is symbolized by fire, then God and salvation must be symbolized by water, and water symbols flow through O Brother like, well, I’d have to say like water I guess. The churchgoers in the forest walk down to the river, where their sins are washed away, the sirens pretend salvation while washing their clothes, Pappy O’Daniel, selling his biscuits on the radio, reminds his pious listeners to use “cool, clear water” in their recipes, a flood comes to save Ulysses and his pals, and even Pete’s cousin, who frees them from their chains, is named “Wash.”

(Then there is the moment where Sheriff Cooley almost lynches Pete by torchlight during a thunderstorm, and even makes a reference to the “sweet summer rain,” the Devil, we might say, quoting scripture to suit his purpose.)

The flood at the end of O Brother is caused by the building of a hydroelectric dam, the dam that’s going to bring enlightenment to the South. Which would make Franklin Roosevelt God, I guess, but it’s worth noting that George Nelson, in his final appearance, rejoices that it is electricity generated by this dam that’s going to shoot through his body and make him “go off like a Roman candle.”

(Radio is a force explicitly linked to God in O Brother — the soul-saving music goes out on it, Pappy O’Daniel depends on it for his campaign, and, at the climax, when Ulysses tells Cooley that the governor himself has pardoned him, on the radio, Cooley’s icy reply is “Well we ain’t got a radio.”)

MAGIC: There is a higher percentage of supernatural occurrences in O Brother than usual, or so it seems. Pete gets turned into a toad, but then it turns out not, the Devil buys Tommy’s soul, or maybe not, God saves Ulysses, or maybe that’s just the federal government. There is a balancing act going on all through the movie, every time something mysterious happens another explanation soon comes along to render it mundane. Magic is mostly cleansed from the narrative, but doubts still linger — in the final shot, the Magic Negro who advises Ulysses in Act I is seen still pushing his handcar across the railroad tracks of the New South.

“Everybody’s lookin’ for answers” in O Brother — some turn to racism, some turn to crime, some turn to sex, some turn to old-time religion, some turn to political reform. Penny’s daughters turn to her. The only answer that seems to be “right” is music, which seems to be able to heal all wounds and knit together a sundered society.

THE MELTING POT: Ulysses and his wife, Dan Teague and Pappy O’Daniel are all Irish-American. I don’t know where Delmar is from, and as for the Hogwallops, well, your guess is as good as mine. (Dan Teague, I’m guessing, is a reference to “McTeague,” the protagonist of Eric von Stroheim’s Greed. Other characters seem to be French-American, such as the Radio Station Man, and then there are the Afrian-Americans, largely unnamed (except for Tommy Johnson, the Robert Johnson stand-in) who make up a kind of Greek chorus.

The movie starts with the image of the chain gang singing a spiritual and ends with the image of a photograph of a rebel soldier being washed away in a technologically-induced flood. There are centuries of history in those two images, tracing the history of the south from slavery, the Civil War, through Reconstruction (which gave birth to the KKK), widespread poverty, the Depression and the Tennessee Valley Authority, which, as Ulysses notes, created a New South, literally washing away centuries of backward living, superstition and corruption (I remember visiting relatives in the South in the 1960s, and there were still plenty of people who were the first in their families histories to own telephones). Which is all very interesting, but one must note, what does that have to do with us?

I think O Brother, in a way, is about the internet. In the same way that radio (and then television) changed the way America saw itself, the internet is doing the same thing to the world. The language that Ulysses uses to describe the New South (“They’re going to run everyone a wire, hook ’em up to a grid”) could be applied with greater accuracy to our global situation today. And, without a doubt, we find ourselves in the middle of another cultural cross-pollination, which, according to the philosophy of O Brother, will save us from ourselves.

Following this metaphor would mean, of course, that America in AD 2000 was a nation of racist, intolerant, superstitious, backward-thinking yahoos. Oh, wait.

One nice thing about the generosity of O Brother is that it is not absolute. Pappy O’Daniel is, without a doubt, a corrupt, cynical politician, and is still very much in charge at the end of the movie. We like him better than we like Horace Stokes because Stokes is a blatant racist and O’Daniel endorses mixed-race music, but even in Ulysses’s moment of redemption there is still a threat behind O’Daniel’s endorsement — O’Daniel will pardon Ulysses only if he promises to go straight, which Ulysses promptly does. But, given the moral universe presented in the movie up to that point, it’s hard to imagine Ulysses being very happy working a straight job.

ECHOES: O Brother features the second of (to date) three scenes in Coen Bros movies where escaped fugitives have peculiar conversations with clerks in roadside establishments.

Another long, awkward elevator ride?

Perhaps, but man, dig that crazy sound.

Karlheinz and Ike, two great 20th-century composers, rest in peace.