Screenwriting 101: Le Trou, and The True

I’m very angry that I’ve gone this long and nobody ever bothered to tell me about Le Trou, Jacques Becker’s exemplary 1960 prison-break movie. What am I paying you people for?

Diary of a Country Priest

So I’m watching Robert Bresson’s 1951 classic Diary of a Country Priest, which is a wonderful movie, but I can’t get over the fact that the protagonist, a soft-spoken, painfully sensitive young man, bears an uncanny resemblance to the young Johnny Cash.

And while it doesn’t exactly interfere with my enjoyment of the movie (both men have health problems, struggle with issues of faith, and wear black all the time) I have to admit that every once in a while I find myself imagining the young priest, while struggling to counsel some troubled parishioner, picking up a guitar and launching into “Get Rhythm.” Which is probably not the effect the filmmaker intends.

Movie Night With Urbaniak: Army of Shadows

I’m in the middle of writing a script, so my movie-renting rate has plummeted in the past few months. Several times I’ve thought about canceling my membership at Cinefile and the other day I walked into the store intending to do so (after returning my copy of Heaven’s Gate, which I’d had for a month). But they had a copy of Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1969 French Resistance thriller Army of Shadows available, so I thought “Well, let’s hold off on canceling the membership for the moment.”

(What you have to understand about Cinefile is that, as the only decent video store on the west side, all the good stuff is always out. Their copy of Vanishing Point was checked out last Easter and has never returned.)

I’ve seen a couple of Melville’s movies before, Bob le Flambeur and Le Cercle Rouge, both of which I watched in my research on heist movies. There is something of Melville in Tarantino I find, with his emphasis on emotional intensity and subverting genre expectations, and his de-emphasis on plot mechanics. Although Melville’s characters don’t sit around yakking about pop-culture phenomena of the 70s.

Which is entirely apt. We’ve got a bunch of guys in a situation. The director just drops us right in, tells us nothing about what’s going on, tells us nothing about who is who, where they are going, what are the stakes, who’s against who, just drops us into the situation and lets the emotional stakes of the scene carry the drama. And the American screenwriter in the audience is racking his brain trying to figure out who is who and where are they going and who is trying to kill who and who can the protagonist trust, and it takes him a little while before he figures out that he’s working against the intent of the filmmaker. The whole point of Army of Shadows is, it turns out, putting the viewer into the same situation as the protagonist (who is a high-level Resistance member). The protagonist doesn’t know who he can trust, so neither does the viewer. The protagonist doesn’t know what’s going to be waiting for him in the next room and neither does the viewer. The protagonist doesn’t know if he can trust the guy sitting next to him, the barber shaving his neck, the man driving the car, and neither does the viewer. The result is electrifying cinema, a movie that dares you to breathe as its characters move through a shadowy twilit world of betrayals and heroism, toward an ill-defined goal and with no reward in sight.

So it turns out, not only do you not have to know much about the French Resistance to watch Army of Shadows, it’s actually a benefit. The movie has very little plot, it’s more of a series of long set pieces describing a chain of physical experiences. This is what it’s like to make friends in a concentration camp, this is what it’s like to have to kill an informer for the first time, this is what it’s like to escape from a Gestapo interrogation, this is what it’s like to bust a guy out of prison, this is what it’s like to be shoved out of a British airplane, with no preparation, in the middle of the night, over what landscape who knows. Every scene, every gesture, every noise on the soundtrack is filled with possibilities. Is there going to be a bomb in this box, or just a shirt? Is the antique dealer going to turn out to be a spy? Is it enough to get through the Gestapo at the train station, or will there be Vichy gendarmes at the Metro station as well?

Melville creates and sustains an absurd level of suspense and intrigue for a movie lasting over 2 hours, which is astonishing when you consider that the movie has very little plot and absolutely no overselling. The shooting style is as declarative and understated as possible; as Urbaniak kept noting, it’s just: “This is what it was like.” The movie doesn’t grab you by the lapels, it doesn’t show off its brilliant technique, it doesn’t dazzle you with clever writing or breathtaking visuals — it doesn’t need to. The situations are so intensely dramatic all by themselves, any more emphasis would be gilding the lily.

Another sterling transfer of a wonderful new print by the ever-reliable folks at Criterion. And for a wonderful essay on the history and background of the movie, look no further.

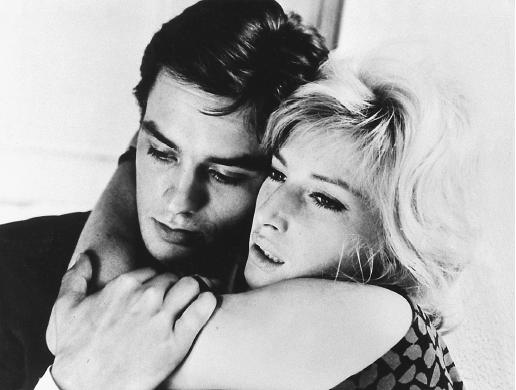

Movie Night With Urbaniak: L’Eclisse

YOUR ATTENTION, PLEASE: This post was originally at least twice as long. Somewhere in the posting of it, half of it got mysteriously eaten by some livejournal program glitch. This makes me angry, but I currently don’t have the time or energy to re-write it. Suffice to say, I liked this movie and so did

.

[beginning of original post]

You know how I mentioned last time around how L’Avventura has no plot, yet is still tremendously exciting? Well, L’Eclisse has even less plot than L’Avventura, and is even more exciting. It’s almost like Antonioni is daring himself to stretch this method of designing narratives as far as it will go.

[significant portion of post mysteriously eaten here.]

[description of first 50 minutes of the movie — Vittoria’s difficulty with relationships, her restlessness, her discomfort, her flight to Verona]

[we join the post half-way through — I am describing a rather amazing 10-minute scene set in the buzz and flurry of a bad day at the stock exchange]

Urbaniak says, “the best extra work of all time.” I mean, it’s really quite stunning, it’s a hugely complicated scene, certainly as complicated as, say, any Hitchcock suspense scene, and as exciting, but like I say, it’s even more of an impressive stunt because we have no idea what it has to do with anything.

Anyway, Vittoria’s mother is there at the stock market, as usual, but today she’s really upset because she’s losing all her money. The market takes a downturn and stays there and everyone is quite upset by the end of the day. And Vittoria shows up toward the end of the day, wondering what all the excitement’s about. She knows nothing about the market and less about crashes (“But if someone lost the money, then surely someone else had to get that money — right?” she asks, hopefully).

10. Piero points out to her a man who has lost 50 million lira in the day’s trading, a sad, overweight, bespectacled man who wanders silently out of the marketplace, and I say “it would be great if the movie now just suddenly dropped everything and followed that guy around,” which, much to my amazement, it then proceeds to do, for about five minutes. Vittoria follows him as wanders, a little shell-shocked, around Rome, much like we’ve watched Vittoria wander shell-shocked, only we know the reason for this guy’s discomfort. But it seems Vittoria sees a kindred spirit in this man who’s lost everything and doesn’t quite know how that happened. She tails him to a little cafe, where he sits down and busies himself with a pencil and paper. We think maybe he’s writing a suicide note or a letter of resignation, but when Vittoria (and we) finally see the paper, it’s covered with childish, even girlish, drawings of little flowers.

11. Vittoria takes Piero to her mother’s apartment for some reason, I don’t know why. She barely knows him, only that he’s her mother’s stockbroker (and her mother now owes him quite a lot of money). We see the room where Vittoria grew up and learn that her father died in the war and her mother is terrified of poverty. As is everyone, quips Piero, but Vittoria says that she never thinks about it. Or being rich either. And we realize that Vittoria doesn’t seem to have given much thought to anything in her future at all — she just kind of blindly gropes forward, hoping the next thing that comes along won’t be quite as much of a dead end as the last thing. She flirts with Piero, then shies away, then flirts with him again. Mom comes home, worrying about where she’s going to get the money to pay Piero — she’s already hocked all her jewelry.

12. At Piero’s office, Piero’s boss tries to explain to the workers how they’re going to get through the crisis of the next stock cycle, how it’s vital to get the money lost from the deadbeats who’ve lost it. Piero needs no coaching on this — he’s regular monster when it comes to making investors feel like losers and idiots for trusting him with their money. And like I say, suddenly we’re seeing everything from Piero’s point of view instead of Vittoria’s. And while Vittoria is vaguely unhappy and fidgety and uncomfortable with everything, Piero is a callous heel who doesn’t seem to have a thought in his head beyond eating and drinking and screwing and doing business — which is to say he’s a stockbroker.

13. After work, Piero, at a loose end, drives over to Vittoria’s place and woos her beneath her balcony (aha! So the Romeo and Juliet reference was intentional!). Why is he attracted to her? Does it have something to do with her mother owing him a great deal of money? More to the point, what does she see in him? Anything? Or is this just how she is with men, just kind of wandering in and out of relationships, not really knowing what she’s doing there, not really having the will to break away? While Piero’s chatting her up, a friendly drunk steals Piero’s pricey sports car and drives it away. This bothers Piero, but not enough to stop him from trying to get a leg over with Vittoria.

14. Next thing we know, the drunk (I think) has crashed Piero’s car and it’s getting fished out of the river. Vittoria is a little horrified by this, but Piero is only concerned about whether or not it will greatly affect the car’s resale value. Everything in the audience’s will screams for Vittoria to go far away from this cad, but she spends the afternoon wandering around the suburbs with him anyway, strolling past a number of rapidly piling up symbols — baby carriages, priests, a recurring horse-drawn cart, and most important, a half-finished new building and the stacks of construction materials surrounding it, which get treated to many disconcerting, lingering closeups.

Vittoria grabs a balloon off a baby carriage, then sends it aloft to her not-very-good friend Marta’s balcony. Marta, the daughter of the big-game hunter, obliges her by getting her father’s elephant gun and blowing the balloon into atoms.

As Vittoria tries to decide to let Piero have his way with her, she rather strangely plunges a chunk of wood into a rain barrel on the new building’s construction site. It’s an odd moment, but it gets odder still, as we will see.

15. Later that night, Vittoria calls up Piero but then doesn’t say anything when he answers.

16. Several times before the end of the movie, we cut back to that chunk of wood in the rain barrel. I don’t know why, but apparently the chunk of wood means something. Is it Vittoria’s soul? Are we checking to see that her soul is remaining afloat? Or is it hope that floats? In any case, the chunk of wood starts to take on significant emotional significance. We want to shout out “go chunk of wood! float! float! float!”

17. Vittoria allows Piero to take her up to his place. Piero is just as big a heel in his own apartment as he is in public. Even though he grew up in this apartment, he has no connection to anything there and seems to have no inner life. He’s decorated the place in cheap bachelor-pad decor and keeps his supply of nudie novelty pens in the study. To underline the metaphor succinctly, he offers Vittoria a chocolate from a box, but when he opens it he finds that the box is, in fact, empty.

Vittoria and Piero fidget around in this apartment, trying to figure out how to start this love affair the two of them apparently want to have, not knowing quite how to do it. The sequence is almost as long as, and serves as a bookend to, the first scene with Riccardo — there, Vittoria was stumblingly trying to figure out how to leave a guy, here she’s trying to stumblingly figure out how to get together with one. “Around you I feel like I’m in a foreign country,” she says, and we know exactly what she means. To make his point succinctly, Antonioni has their first kiss happen through a pane of glass.

The tag line for Annie Hall was “A nervous love story,” but that fits L’Eclisse even better. Both of these beautiful young people are absurdly nervous about something — love or “the world” or something, I don’t think they know. I think Antonioni knows, but I don’t think he wants to tell us — that would somehow ruin everything.

They apparently finally get it on, and Vittoria, for a moment or so, seems happy. Why, we don’t know.

18. Then — crisis! The rain barrel leaks, spilling its water into the street and down the gutter. The camera lingers on this for a long time, the water gushing out of the rusted barrel, Vittoria’s special chunk of wood, her stick of hope, swirling around helplessly as water level drops.

19. Then, as a denouement, some buildings, some faceless people wandering around the cold, modernist, characterless suburb, and a curtain call of symbols. The baby carriage again, the priest, the horse and carriage. A sprinkler is shut off. A modernist streetlamp comes on. There’s that building again, with its heaps of unused construction materials. A man gets off a bus carrying a newspaper — the headline is something like “ARMS RACE SHOWDOWN” and “A NUCLEAR SHADOW,” which almost ruins the whole movie. It’s like Da Vinci writing at the bottom of the Mona Lisa, “She’s smiling because Italy has justemerged from a thousand years of church-dominated ignorance.” Does the H-bomb account for Vittoria’s discomfort, for Piero’s callousness, for the stock-market crash? Is that what the movie is finally “about?” Or is the nuclear threat only a symptom of something else, something harder to put one’s finger on? Because these answers are harder to come to, ultimately I think L’Eclisse is a more daring and accomplished movie than L’Avventura — Antonioni here really seems to be on the verge of something profound. This is tough, unsentimental, rigorous, hugely disciplined filmmaking, with the highest of artistic aspirations — no wonder the purists are so upset by Blow-Up, which is stylish, superficial and glib in comparison.

In the closing moments of the movie, a jet plane flies overhead. The sound-effect geek in me cannot help but note that the “jet plane” sound used is the exact same recording heard a few years later at the beginning of The Beatles’ recording “Back in the USSR.” Coincidence or incredibly-obscure homage? You be the judge.

Movie Night With Urbaniak: L’Avventura

The first thing you need to know about L’Avventura is that it has no plot. The second thing you need to know about L’Avventura is that, in spite of having no plot, it is still tremendously exciting.

I don’t know how it manages to do that.

This was a rare instance of

actually requesting a movie to watch, rather than the two of us just kind of pawing through my DVD collection until we find something we both want to watch. He showed up with the movie clutched in his slender, spidery, indie-stalwart hands, still it its shrinkwrap, still with the price tag from Amoeba on it.

The movie is loaded with symbolism, but the characters aren’t symbolic — they’re real people. At least I think they are. Every time I tried to read the movie as purely symbolist it would answer with a scene that said that it was actually a character study.

Come to think of it, the story structure kind of reminds me of Raymond Carver. It’s not about big moments, or about a coherent dramatic arc. It’s about these people caught in a situation and it kind of sits there and studies how the people behave. And all the incidents that make up the narrative are all really small and not necessarily significant in and of themselves, but are so specific, and so ineffably cliche-free, they retain our interest. We keep watching partly because we want to know why the people are doing the things they’re doing and partly because we want to know why the filmmakers chose to shoot the scene. What do all these little moments of behavior add up to? Will the trashy celebrity who shows up in Act III show up again in Act IV? Why this town, why this church, why this shirt, why this room, why this hour of the day? Resonances and echoes show up all over the place (just like they show up in that scene with the church bells) and every time you think a scene isn’t going anywhere the scene goes somewhere, but never where you thought it was going.

In other ways, the story structure reminds me of Kubrick, in that there are long slabs of narrative dedicated to illustrating one plot point and we don’t know what the plot point is until we arrive at it at the end of the slab. Those slabs are, roughly:

1. Let’s go on a cruise! (30 min)

2. Looking for Anna (30 min)

3. Will Sandro get a leg over? Will Claudia give in? (30 min)

4. Claudia commits (30 min)

5. Crisis (17 min)

1. So there’s this woman, Anna. She’s young and Italian in 1960. She was probably a child during the war. Her father is a builder of some sort. We first see her have a halting conversation with dad in front of one of his building projects. He’s tearing down some old buildings to put a new one there.

says that’s a major theme of the movie: destroying down the old to make way for, what, exactly? The anxiety of that question hangs over the entire narrative.

Anna’s in love with Sandro. Or maybe she isn’t. Claudia is in love with Anna. Or maybe she’s in love with Sandro. In any case, there’s a lot of unspoken tension between the three of them. Maybe Anna isn’t really happy with Sandro and would rather go with Claudia. Maybe the opposite is the case.

This bunch of funsters go on a cruise in the Mediterranean with some friends. Their friends’ relationships are, to put it mildly, dysfunctional at best and doomed at worst.

Theyarrive at an island. Folks go swimming, folks climb on rocks, folks bicker.

2. Somebody notices Anna isn’t around any more. The group searches the island. They call the police. The police and whatever authorities do things like this search the island. For 30 minutes we watch people climb over rocks and gaze into the water and wonder what the hell happened to Anna. Because either she’s hiding, which is unlikely, or she’s unconscious somewhere we haven’t looked yet, or she’s dead somewhere we haven’t looked yet, or she got on a boat we didn’t see and rode off somewhere. If she’s dead, she could be dead by suicide or by murder or by accident.

3. Apparently Anna is not on the island and nowhere near the island. The other couples go on with their vacation while Claudia worries about Anna and Sandro half-heartedly searches a nearby town. I say half-heartedly because, well, for some reason Sandro, now that Anna is gone, doesn’t want to waste the opportunity to make a move on Claudia. Claudia is horrified by Sandro’s advances — her friend-girlfriend -Sandro’s-girlfriend is missing and she feels guilty and terrible about it — this is no time to be messing around the ancient, tumble-down towns of rural Italy.

The narrative starts to splinter here as Sandro gets distracted and Claudia gets anxious. Sandro runs into that trashy celebrity mentioned above, Claudia gets caught at a society gathering refereeing for her non-friend Giulia’s (or is it Patrizia’s?) makeout-session with a Bob Denver-lookalike teenage artist, whose paintings are an affront not just to the beauty of the villa where he’s staying but an affront to their subjects and to the act of painting itself.

4. Claudia suddenly, and without preamble, gives in to Sandro’s advances and declares herself desperately in love with him. Maybe she’s been in love with him from the beginning, maybe she’s just recently decided she is, maybe she’s fooling herself. We know Sandro is a lout who has no idea what love is, that seems clear enough, but Claudia seems to be cut from different cloth. First, she’s the only one on Team Ennui who wasn’t born wealthy, second she’s the only one who carried any sense of guilt about Anna’s disappearance all the way through Act III. This is where I started to think L’Avventura is about postwar Italy, how a new generation chose to move ahead into some ill-defined bright tomorrow while others couldn’t help but feel a sense of guilt and loss for what had been destroyed in the war. In any case, loss, the careless destruction of the old and beautiful, the replacement of the old and beautiful with the new and ugly (and profitable) is one of the movie’s ongoing concerns.

griped toward the beginning of the movie that he didn’t like the actor playing Sandro, that he was uninteresting and shallow, giving a kind of generic “60s leading man” performance. By the end of the movie he had changed his tune, realizing that the actor was not giving a shallow performance, he was performing the action of being shallow, which is a completely different thing. That is, it’s not the actor who is giving a generic “60s leading man” performance, it is Sandro who is giving it. As Act IV goes on and Sandro starts to reveal his true ugliness, shallowness and restlessness he becomes infinitely more interesting. Conversely, Claudia, once she gives up on honoring Anna and gives in to Sandro’s indelicate advances, becomes slightly less interesting as she pines and swoons and tries on different outfits.

Why does Claudia fall for Sandro? We don’t want her to. If she always had a thingfor him, she’s an idiot, and she doesn’t seem to be an idiot. I prefer to think that both Sandro and Claudia had a thing for Anna and when Anna vanished she created a kind of relationship black hole that sucked Claudia and Sandro toward each other. Claudia becomes attracted to Sandro because they now have something in common — missing Anna.

Let’s say for the moment that Anna is a symbol for something really pretentious like “the soul of Italy.” The soul of Italy has vanished and only Claudia seems to really care about any of that. Sandro doesn’t care — he made his peace a long time ago that he wasn’t going to create anything beautiful. He had his chance — he coulda been a contender architect, we learn at one point, but gave it up for the short-end money. Then we see him knock a bottle of ink over onto a drawing someone’s making of a gorgeous church window. Sandro cares about the soul of Italy insofar as he wishes to destroy it as quickly as possible. To replace it with what? Well, that’s where Sandro’s anxiety comes in. He doesn’t have any idea what he’s going to replace it with. Maybe that’s why he makes such a fast move for Claudia — he’s just reaching out for the nearest available object to replace the hole in his soul that opened up when Anna disappeared.

5. Sandro and Claudia, having declared their undying love for each other, check into a hotel where their friends are staying. There’s a big party going on. Claudia is tired and wants to stay in the room, but Sandro gets duded up in his tuxedo to check out the action. Claudia can’t sleep and mopes around the room while Sandro wanders, bored and restless, among the empty suits and fashionable gowns. He sits down to watch a TV show in the hotel TV room. We don’t see what’s on TV, but it seems to be a show primarily about things that go “WHOOOSH!” He watches this scintillating program for a few seconds before wincing at it and moving on.

Claudia suddenly has a vision that Anna has returned, which she feels would be really bad at this point because it means that her love with Sandro would be doomed. She rushes downstairs to the empty ruined ballroom and finds Sandro making out with the trashy celebrity from Act III.

Claudia dashes out of the hotel, as one does in situations like this, and Sandro chases after her. (The trashy celebrity begs Sandro for a “souvenier” and he disgustedly throws a wad of money at her. She lazily gathers it up with her bare feet like an octopus capturing its prey.)

Sandro collapses on a bench and cries. Does he feel something? Is he worried about losing Claudia? Is he mourning Anna? Is he mourning his own soullessness?

Claudia approaches. A satisfying ending would be: she hits him with a big rock and screams “I KILLED ANNA AND ATE THE BODY, YOU FOOL!” But that’s not what happens. She should, at the very least, be very angry at him — he went pouncing off after Paris Hilton mere moments after declaring his unending love for Claudia — and did so while Claudi was right upstairs! But we watch as she balances that anger for a moment, as she literally balances her own self, gripping the back of the bench to keep herself upright. Then she places a hand on Sandro’s shoulder, as though to forgive him, then, incredibly, she moves her hand up to his head, to pull him to her, to comfort him. We have no idea what happened to Anna, all we know is she’s gone and, as far as the movie is concerned, isn’t coming back.

(Idea for sequel: L’Avventura II: Anna’s Return!)

And then the last shot, reproduced above. Half mountain, half ruined building, the wounded, conflicted, embattled couple facing their uncertain future. “The ‘adventure,'” says

, is the couple’s adventure into adulthood.” “And Italy’s adventure into the future,” I add, half-heartedly, because I’m really not sure.

Movie Night With Urbaniak: Yukoku, Z

Two political thrillers of extremely different stripes this evening. The first, Yukio Mishima’s short 1966 film Yukoku and then Costa-Gavras’s 1969 political thriller Z. The two movies could not be more unalike: Yukoku is brief, stark, weird, highly stylized and almost freakishly intense, Z is naturalistic, frenetically shot and edited, alarming and intensely furious. The fact that they were made around the same time and come from polar opposites of the political spectrum make the evening that much more fun.

Yukoku is based on a short story published in the US as “Patriotism,” which is essentially a dry, clear-eyed, blow-by-blow account of an army officer committing seppuku. The movie is much more stylized, artsy even, with its abstract sets, lack of dialog and dramatic lighting. The officer comes home, greets his wife, explains the situation with her, she agrees to also kill herself, they have serious, intense, dramatically-lit sex, he gets dressed and kills himself, she goes and puts on fresh makeup, then comes back and kills herself too. A lot of Mishima’s key themes are distilled into this 25-minute movie — the changing nature of Japanese culture (which Mishima despised, being politically conservative in the extreme), the importance of dying while still beautiful, the tying together of sex and death and the compulsion to make one’s death a work of art. (Of course, most people these days watch Yukoku, if they watch it at all, because Mishima later killed himself in a manner startlingly similar to what he does in this movie.)

Mishima, surely one of the most egotistical men of his day, strangely declines to give himself a single close-up in this most personal of stories. Instead, he hides his face behind the bill of his army hat through the whole movie, giving all the close-up time to the actress playing his wife. She becomes, essentially, the protagonist of the movie — the army officer remains opaque and unknowable, while his wife (and by extension, we) are meant to fall desperately in love with his noble honor and tragic beauty. After her husband dies, the wife goes to freshen up and there is a terrific shot of her silk robe dragging through the pool of her husband’s blood on the floor. On the one hand, one says “ick,” but on the other hand, the shot drips (sorry) with symbolism and beauty, which kind of sums up my feelings about Mishima in general. On the whole, I’d rather he go on making experimental films instead of killing himself in a meaningless political gesture, but then I probably wouldn’t be sitting here thinking about him.

Z is a whole different kettle of fish.

Here in the US, we’re completely comfortable watching movies about Russia or Italy or Spain and seeing American actors speak English with cheesy accents — we don’t think a thing about it. But when watching Z, it’s disorienting for a while because it’s a movie set in Greece about Greek people but is shot, um, somewhere that’s not Greece (I think French Morocco), starring an all-French cast speaking French. On top of that, the filmmakers have made the decision to not try too hard to make their locations look authentic, which means that it feels like all you need to know is that it’s a political thriller that takes place in some sunny country. (At the time of course, the story was not only fresh but still going on, so none of this had to be explained to anyone.)

For the first half, it’s a political thriller par excellence, shot with such verisimilitude as to be startling and confusing. Nothing is explained, nothing is slowed down for the newcomers or Americans. There’s some kind of country, and it’s run by some kind of quasi-fascist regime, and an opposition leader is coming to town for a rally. We see the rally organizers trying to nail down the specifics of their upcoming event, we hear that there is a threat of assassination in the air, we see the general political unrest in the streets. We (at least we in 2007) don’t know which side anyone is on, who to root for, or even who the protagonist is. We’re just kind of plunked down in the middle of this situation and left to fend for ourselves. The shooting is all documentary style, handheld cameras and whipcrack pans, with a few artsy little flourishes, and then just when we’re getting oriented to who’s who and what’s at stake, the opposition leader gets assassinated and the movie changes gears.

53 minutes into the narrative, the protagonist shows up, the special prosecutor hired toinvestigate the assassination, and the movie becomes a detective thriller as we watch the prosecutor gather evidence, track down leads, and piece together the chain of events that led to the assassination. It’s almost unbearably thrilling, because we are in the exact same situation as the prosecutor — we just got here, we saw everything happen but we have little idea what any of it means. So as the scope of the conspiracy becomes clear and the stakes rise, our anger towards the people responsible gets greater and greater.

I first saw this movie in 1981 or so and thought “Wow, fascinating, what interesting places these horrible little tinpot dictatorships are,” and last night, of course, James and I could not help but be reminded of what our country is going through right now. We watch as government officials edit intelligence reports to fit a pre-decided outcome, twist and distort language to serve ideological ends, smear, intimidate and destroy their political opposition and finally kill anyone who disagrees with them, banning the use of language itself when it contradicts the official viewpoint, and it’s like being granted a backstage view at the White House. Halfway through the movie, I had a vision of the 28-year-old Dick Cheney watching this movie in 1969, watching how the fascists operate and whipping out a notebook, nodding along, saying “uh huh, got it, good, oh that’s a good one, yes, ah yes, indeed.”

Late in the movie the prosecutor is delivering his findings to his government superior, who grows increasingly upset as the story is accurately assembled before his eyes. The prosecutor, who has no agenda other than finding out who done it, turns up his palms, almost apologetically, and says “these are simply facts,” which is, of course, why his boss is so upset, and which is why the scene resonates with us so strongly today. We live in a country where the simple stating of facts is considered a dangerous left-wing attack on the government.

The fascists of Z despise modernism, long hair, rock music, liberalism and lack of respect for the government. One wonders whose side Mishima would have been on while watching the movie.

Code 46, Dark City, Metropolis

Texture is important.

These three movies have very little to do with each other, except that they are set in imaginary societies where people’s freedoms are curtailed in ways we would find objectionable, and they were all at the video store at the same time as I was looking for Futuristic Dystopias to study. And I suppose you could say that all three have male leads who are very good actors but stop short of being movie stars.

(Incidentally, if there’s one thing all nightmare futures have in common, its that they all predict less freedom for their citizens. Why won’t anyone make a movie about a nightmare future where everyone has too much freedom? Well, I suppose that’s Idiocracy, actually.)

For my purposes here, they also all point to the importance of texture in this kind of movie. I know this from Blade Runner, but Ridley Scott knew it from Metropolis. If you get it wrong, your dark, futurist nightmare dates quickly, feels constrained and silly. If you get it right, the texture makes the movie worth watching all by itself.

The Man Who Fell to Earth, for instance, is an example of a movie with a lot on its mind, but very little effort is spent on making us believe we are seeing the future. The Island, meanwhile, has expended tons of effort in bringing us a vision of the future, but has very little on its mind.

SPOILER ALERT

The future of Code 46 seems completely plausible, almost here already. The cars are the same cars we drive now and the buildings are the same ones we work in. Apartments are smaller and have computer screens built into glass walls, and some quirky new words have worked their way into the language (like “papelle” and “cover” and “outside”), but there have been no radical leaps forward in fashion or architecture. Tim Robbins and Samantha Morton meet and fall in love and that creates problems for them, but none of the weird things they have in their lives feel any more novel to them as computers and cell phones seem to us. Designer “viruses” are just a part of their everyday life, along with “new fingers” and “memory albums” and the remote possibility of having sex with the clone of one’s mother. Director Michael Winterbottom even has the actors pitch their dialogue in a rushed murmur so that we have to lean forward to catch what they’re saying. It doesn’t feel like a movie about the future, it feels like a movie from the future, in the same way that Barry Lyndon feels like a movie about the 18th century made in the 18th century.

Dark City is a, well, it’s a weird movie. A bunch of aliens have abducted a bunch of Earthlings and built a pretend city for them in the middle of space so they can study them and learn about the human soul. For some reason, they’ve decided to make the city a Fake New York circa 1940s. At the end of every day, the aliens stop time and rearrange the city, along with everyone’s lives, then start up time again to see how people react. Rufus Sewell is an Earthling who, for whatever reason, cottons to the aliens’ plan and finds himself able to rearrange physical matter his own self. (The movie is so weird that telling you all this doesn’t really even give anything away — all this is revealed within Act I.) The texture here is overstuffed, overheated, delirious. Cityscapes are obviously, unapologetically miniatures or computer-generated, doorways melt or appear out of nowhere, leading to streets, outer space or plunges. Furniture stretches, walls expand, dishes and tchotchkes appear out of nowhere. Streets are too narrow and lead to nowhere, everything feels like a movie set, which is partly the point. It all works toward creating a sense that anything might happen. Sort of funhouse version of The Matrix.

Metropolis is still the gold standard for this kind of movie. The sets and effects, mind-blowing for their time, are still mind-blowing 80 years later. The plot makes as much sense as Dark City, with the same kind of delirium present as well, but also carries with it a Serious Message about class warfare. The son of an industrialist falls in love with a mysterious crusader and learns about the sorry life of the workers who make Metropolis run. The industrialist father, wishing to put the woman’s crusade to an end, asks a scientist friend to give his newly-created robot the face of the crusader, then train the robot to go and tell the workers to give up. The scientist has his own personal vendetta against the industrialist and gives the robot-woman instructions to get the workers to revolt against the city thus provoking an apocolypse that threatens to kill the workers’ children, start a revolution and kill the industrialist’s son. With a plot like that, the visuals better be pretty fantastic, and Metropolis does not disappoint; it’s stuffed full of gigantic, complex sets with swelling tides of humanity coursing through them. And the special-effects aren’t impressive “for their time,” they’re impressive for, say, 1977. The effect is incalcuable. The mighty cityscapes with their elevated walkways, spotless streets and canyon-like vantages give an impression of overwhelming inhumanity while still maintaining their beauty and power.

(The theme of Metropolis, stated many times throughout, is “The Head and Hands must have a Mediator, which must be the Heart.” Lang doesn’t seem to be arguing that the upper class is bad, just that they need to keep in touch with the lower class who make their machines run and maybe don’t be so cruel to them. Otherwise they seem to be perfectly nice people.)

The current Kino Video release is also the most complete assemblage of film elements of this movie and a near-complete restoration, and the results are jaw-dropping. The print looks brand-new, scratchless, spotless, bright and lustrous. As an added bonus, the score of the original run has been re-recorded, the goal being to present the movie as close as possible to its original premiere. I’ve seen Metropolis before, but this felt like a completely different movie.

Jules et Jim

This is my idea of a holiday. I have no meetings for a week, I don’t have to think about Futuristic Dystopias or Moby-Dick or The End of the World for a few days, so I can indulge myself and watch a movie like Jules et Jim. It is especially gratifying to see this after watching the stiff, leaden Fahrenheit 451, made a scant three years later. It couldn’t possibly be more different and could have used one-tenth of the energy or powers of observation that Jules et Jim has.

I was reading an interview with Woody Allen where he talks about Bullets Over Broadway and how he loved shooting Husbands and Wives with the hand-held shaky-cam jump-cut style but that you couldn’t do that with a period piece because people have a certain mindset about how the past should look on film. But that’s exactly how Truffaut shoots the same time period in Jules et Jim, tossing in freeze-frames and wild pans and rushed zooms and a dozen other techniques that remind you that you’re watching a brand-new movie about events fifty years in the past. The first act of the picture, where Jules and Jim meet Catherine and World War I hasn’t happened yet, is so breathlessly (pun not intended — at least I don’t think so) shot and edited and with such quicksilver energy that it takes a moment to realize that everyone is wearing funny clothes and driving vintage automobiles. Truffaut cuts as often as Michael Bay; scenes and images fly by with the speedof fleeting memories. How it was all shot I have no idea, all those shots of adventures glimpsed but not explained. Did Truffaut board all those scenes (did he board anything)? Were they scenes that once had dialogue but got cut out, except for those brief shots? It seems like there are dozens of them.

For those unfamiliar with the movie, Jules and Jim are best friends living la vie Boheme in belle epoque Paris. Jules meets Catherine and they fall in love. Catherine is a capricious, complicated woman who also falls in love with Jim, but events conspire to put her together with Jules. They get married and have a child, but Catherine is restless and inconstant and still wants Jim (among other men). Instead of leaving Jules with the child, they invite Jim to live with them in the Rhine valley. Everyone has the best intentions and is full of love, but they cannot keep from causing each other suffering as their complicated love story unfolds.

Catherine sounds like a handful, doesn’t she? And yet, I once knew a woman a lot like her. She was very beautiful and charismatic, loved whoever she wanted to whenever she wanted to for as long as she wanted to, and never gave a thought to how she might be living tomorrow; there would always, it seemed, be someone there to take care of her, give her whatever she needed, indulge whatever whim she might have. I have no trouble buying that such an arrangement might arise between a woman and a pair of of men in Europe between the wars. And such a story could be really pulpy and soapy (if something can be both pulpy and soapy) but Truffaut handles it all with a wonderful dry-eyed realism, with a sympathetic camera and journalistic editing style, letting the story speak for itself.

Imagine my surprise when I learned, elsewhere on the Criterion edition (where else?) that the movie is based on the true story of a clutch of real bohemians in the real Europe of 1914-34 (or so). After watching the thrilling, lyrical movie it’s great to watch the documentary included and hear the stories of the children of all these bohemians, who not only don’t have particularly bad memories of their parents’ unconventional lifestyles but actually mostly idolize them. If they critcise them, it’s for their innocence, not their morality.

Because morality is at the center of the story. In the movie, Jules and Jim and Catherine make up their own rules for living from day to day. Life, of course, imposes its own rules, as life will, and the conflict between the characters and the immutable laws of the universe forces a tragic end to their story. It’s sort of a metaphor for the whole belle epoch lifestyle, legislating its own morality until the Nazis come along with their own vision of morality, one enforced at gunpoint.

In real life however, Jules’s and Jim’s and Catherine’s lives don’t end in 1934. They all go on with their lives, raise children in various places around Europe, make livings in the margins of the literary world, have innumerable other affairs and complicated arrangements (Jim, for instance, after leaving Catherine and Jules, lived with three other women at once, promising to marry “whoever survived”), and live to ripe old ages (Catherine lived to be 96!). Truffaut says that these arrangements must have caused great turmoil and suffering, but his movie is full of joy and life (the tone of which is apparently taken from the novel). He didn’t make a cautionary tale, he made a love story.

Sven Nykvist

Sven Nykvist, sadly, is no longer the world’s greatest living cinematographer.

I am both extremely proud and terribly ashamed to be the author of Curtain Call, Mr. Nykvist’s last film. He was very kind to me, a young, unproven whippersnapper, and everyone else on our crew. He told me a funny story about working with Tarkovsky and expressed, with total good humor, his frustration with working with Woody Allen. My pathetic excuse for a romantic comedy was far below the typical material he worked with and I feel blessed to not only have had him shoot my script, but to actually have lit me for a cameo scene.

I knew that he was a great cinematographer when I was working with him, but like the philistine I am I did not see his work with Bergman until long after we parted ways. Had I seen, for instance, Through a Glass Darkly before I met him I doubt I would have been able to look him in the eye, I would have been too ashamed to work with so great an artist.

Seven Samurai

First of all, there is a new edition of Kurosawa’s masterpiece out now from, of course, Criterion. It’s rather staggering in its quality. If you’ve never seen the movie, you’ll never have a better chance to experience it than now. Even if you own the previous edition, just go out and buy the new one, I’m serious, it’s just rather staggering.

Plenty of words have been spent talking about this movie so I’ll keep this brief.

Kambei (a career-best performance that made me fall deeply in love with Takashi Shimura) seems to have decided that a samurai is something like a warrior monk. When we meet him, he’s actually disguising himself as a monk in order to root out and kill a desperate, kidnapping thief. Later, when a group of penniless farmers ask him to assemble a team to aid their village in battling an army of vicious bandits (also ex-samurai), Kambei accepts the job even though there is no money and no glory involved.

The farmers constantly complain about how poor they are, but in a land where no one has any money, they are the ones under attack because they have the only thing worth anything: food and land. The samurai, once a wealthy, influential class, are now in the same boat as everyone else, and Kambei has apparently decided that when no one has any money, what is valuable is one’s actions, one’s code, one’s behavior. In his case (he is in the minority among samurai) he seems to think that being a samurai involves helping desperate people in need for free. His altruism inspires four other samurai of various background and experience to join the team. One is an old friend, one is a genial goof, one is a remote, opaque killing machine, all represent, again, greatly differing ideas of what a samurai “acts like.”

Then there is Katsushiro, a teenage samurai who attaches himself to Kambei out of fawning idealism, and Kikuchiyo (Toshiro Mifune, in a brave, off-the-rails Depp-like performance) as a drunken fraud who’s only pretending to be a samurai.

Kikuchiyo, we learn, was once a farmer himself, and has promoted himself to samurai out of shame for his background and the supposed glamour and class elevation of samurai. But once we get to the village, we learn that the samurai are despised and reviled by the farmers, who don’t trust the very people they’ve hired (for nothing) to guard their village with their lives. In fact, we learn that the farmers have actually killed other samurai who have passed through, out of fear and supposition of how a samurai acts.

And so Kambei and his team of samurai, wanting nothing but to be helpful and good, encounter nothing but dishonesty, greed, trickery, fear, suspicion, small-mindedness, theft, short-sightedness and stupidity. Given all that, Kambei has every reason to a) say “The hell with this” and leave the village, or b) join the bandits and destroy the place. But he does not; with each affront, he merely gives a discouraged look, rubs his shaven head and gets on with his work. It’s all he knows how to do, and something inside of him tells him that it will all somehow be worth it.

In the end, whether it has, indeed, been worth it, is the movie’s lingering question.

And so the samurai train the farmers to become samurai too, further blurring the distinction between samurai and non-samurai. And soon, everyone in the movie starts questioning their roles, wondering what it means to be a farmer, a father, a man, a woman, a wife, a patriarch. In one key scene, the teenager Katsushiro is romping in a sylvan glen with his farmer girlfriend, and she literally throws herself in front of him in sexual frustration, demanding “Damn you, why can’t you act like a samurai?!” and poor Katsushiro can only stand and stare in trembling fear. And who can blame him? He hasn’t got the first clue how to “act like a samurai.”

(Later on, when Kikuchiyo sits mourning the death of one of the farmers, Kambei chides him by saying “What are you doing? This isn’t like you.” Kikuchiyo has let Kambei down by dropping his facade, by not pretending to be a loud, cockeyed brazen fool for once. I’m reminded by Vonnegut’s quote, “We are what we pretend to be, so we have to be very careful about what we pretend to be.” I’m also reminded that having courage and pretending to have courage are actually the exact same thing.)

One of the samurai paints a satirical banner intended to make fun of Kikuchiyo, but in the end it is Kikuchiyo, the one who admittedly isn’t even a samurai at all, who pulls the team together and turns them into a fighting force. When one of the samurai is killed in a raid, he grabs the banner , climbs to the top of a house and plants it. It whips in the wind and suddenly everyone sees “Yes, this is what we are, the hell with all the suspicion and misunderstanding, we are samurai, no matter what the hell our doubts are, and we’ve got a job to do, so we’d better get our minds together and do it.”

When the bandits finally show up on their murderous rampage, Kambei does not seem fearful or tense; rather, his sense of relief is palpable: finally, a battle, something he actually knows how to do.

When Katsushiro finally gives in to the girl’s demands and “acts like a samurai” on eve of the final battle, the results are devastating. The girl is thrashed by her father for being a slut and Katsushiro is mortified by his actions, even though he was motivated by tender love instead of brutal lust. When the battle against the bandits is won and the farmers go back to their simple, happy lives, Katsushiro is caught in a double bind: his girl no longer needs him, his destiny as a samurai will lead him elsewhere and he still has no idea what he is supposed to do.