Some thoughts on The Boys

It’s a tough time for satire. The Trump Circus is so insane, so flamboyantly, egregiously stupid, that it’s impossible to address it head on. Saturday Night Live gave up a long time ago, it merely sums up the week’s events in a slightly more cartoonish delivery.

In order to satirize the unthinkable, you have to approach it from a different angle. Horror has always been good at this, allowing people to experience the terrors of everyday life through the lens of metaphor. The hellscape of 1968 was perfectly encapsulated in the movie that sprang from it, Night of the Living Dead, and They Live was, if anything, too blunt a metaphor for the Reagan era.

Amazon’s The Boys, based on a comic of the same name, has emerged as the most relevant show of the day, taking all the ugliness, greed, desperation and horror of our present moment and adding just one pop-culture ingredient to make it palatable: superheroes.

The premise, at first, sounds merely waggish: what if the Justice League were assholes? But, like, really, really, unredeemable assholes? But then it goes deeper, much deeper, as it presents a world where there are superheroes, but the superheroes are controlled by a REAL superpower, a gigantic multi-national corporation. This corporation promotes its superheroes as media stars, putting them into movies and TV shows, promoting their Instagram accounts, organizing Twitter armies to sway public opinion about them, creating their personas and origin stories, and, above all, keeping the public constantly entertained by their antics in order to cover up the many, many horrendous crimes they commit.

Does this sound familiar?

The show is not for everyone — it’s not just caustic in its satire, it’s positively scabrous, presenting a harsh, scorched-earth vision of a world where there is no real good, only different aspects of evil. There is nothing pure in its world, nothing is left untouched by its brackish, curdled moral sense. It’s pungently profane, and baroquely gory. People are routinely dismembered and beheaded, when they’re not exploding outright, but, for my money, that profanity and violence is the best mirror we currently have in a world where there really are people above the law, backed by moneyed interests with power beyond our imagining, who blithely circumnavigate the globe crushing the weak beneath their heels.

Batman on the Big Screen

Batman on the Big Screen, a volume collecting everything I’ve written about the Caped Crusader, is now for sale at Amazon. It’s the first in what will be a long line of volumes under the What Does The Protagonist Want? banner. Having just finished editing it, I can tell you, it’s still highly addictive reading!

Superman: Superman: The Movie part 6

Superman reaches its crisis point as Lex Luthor explains his scheme to Superman and Superman stands there and looks shocked. Keep in mind, Superman knows that the army and navy are testing two nuclear missiles that day, and he also knows that Lois is “out west checking into a big land sale,” and yet, as Luthor patiently explains his plan to him, he still puts nothing together on his own and does not act even after Luthor is done with his presentation. Luthor was banking on Superman’s goodness, but he needn’t have bothered – he could have banked on Superman’s total lack of deductive reasoning.

Superman: Superman: The Movie part 5

Ninety minutes or so into Superman, Lex Luthor, in his luxurious basement, puts together a chain of logic that leads to a chance to murder Superman.

Here is his chain: Superman is from Krypton, which exploded. Exploding planets create debris. Debris, drifting through space, becomes meteorites. Meteorites from the exploded Krypton would have specific radioactive signatures. Ergo (his word), a meteorite from Krypton will kill Superman.

Let’s examine this a little more closely. Lex Luthor, by his own admission the most brilliant man in the world, has a plan to kill Superman that involves exposing him to a rock from his home planet. Let’s set aside, for the moment, the fact that no aspect of his chain of logic makes any sense whatsoever. The first question is, why does Lex Luthor need a plan to kill Superman? We know at this point that he has some kind of diabolical scheme in play, but why does that create a pressing need to kill Superman, indeed, a need that supersedes all planning for his nefarious plot? For that matter, why, if Lex Luthor has a diabolical scheme, do we never see him actually executing any aspect of that scheme? Ninety minutes into the movie, all we have seen Lex do is lounge, swim, proclaim his greatness, insult his underlings and bitch about stuff. Whatever his evil plot is, its implementation takes up not one second of his time.

Superman: Superman: The Movie part 4

What does Superman want? It seems like an odd question to ask at this point, but the movie Superman spends its first seventy minutes setting up a conflict between impulses for its title character, and now that he’s emerged, it’s a question worth asking. Once Superman shows up to save Lois Lane, the genie is out of the bottle, so to speak, and the movie, once again, does something odd – it stops for a few minutes for Superman to buzz around town doing Superman stuff. It’s a no-brainer for him to save Lois from a plummeting helicopter (he’s in love with her after all), but then we see him 1) stop a jewel-thief in the midst of a building-climb, 2) foil a robbery getaway, 3) rescue a cat from a tree, and 4) save Air Force One when it is struck by lightning in mid-flight. Saving people (and a cat) is an easy choice, but why does Superman necessarily foil criminals? And, once he’s made the decision to foil criminals, why does he foil only these criminals? Was there really no other crime happening in Metropolis that night? Was the city otherwise a peaceful idyll for the time he spent saving the cat? For that matter, to save Lois Lane is one thing, he’s in love with her (although the narrative has shown no good reason why), but when he makes the decision to save the president over other people (or a cat), he’s making a specific choice. Superman decides who is worth catching and who is worth letting go, and he decides who is worth saving and who is not.

How does this sequence funcion narratively? I’ll tell you, as teenager watching the movie in 1978 (he said, contemplatively stroking his long white beard) the feeling was “Finally, the movie is starting.” This sequence, beginning over an hour into the narrative, is like a title sequence for the rest of the movie. No plot emerges from Superman’s randomly-selected salvations and punishments, but tonally the sequence is a miracle, literally. It presents a world-changing night when suddenly there is a god on earth, nabbing the bad and protecting the endangered. As the first-ever sequence presented in a wide-screen, big-budget superhero movie, it’s a complete game-changer. It’s what we came to see, and the notion that there would be a god out there deciding who was worth imprisoning and who was worth rescuing was a brand-new, very powerful thing in the movies. Not even a Biblical epic could give an audience a secret god, Moses and Jesus and Noah (I can’t think of any others who got their own movies) could never disguise themselves to mete out punishments and rewards. In 1978, America very much needed a way to feel good about itself and Superman suggested that somewhere there was a man, a man with heavenly origins but Midwestern upbringing, who knew what made America great and could show us the way with politeness and good humor. And let it be said that Christopher Reeve rose to the challenge magnificently and became the image of Superman to my generation. When the authors of Kingdom Come dedicated their book “to Christopher Reeve, who made us believe a man could fly,” they spoke for everyone who saw Superman in the theater.

Superman: Superman: The Movie part 3

Superman is 49 minutes old and its protagonist has arrived at his fourth home: Metropolis, for which the movie doesn’t bother disguising Manhattan. Keep in mind, this is not the Manhattan of today, with the theme-park Times Square. This is the Manhattan of 1978, the Manhattan of Taxi Driver and Death Wish, the Manhattan of the 1977 blackout and the looting that followed, the broke Manhattan, the Manhattan Gerald Ford had told to drop dead. In the Manhattan of 1978, it was considered suicide to enter Central Park after sunset. As far away from Krypton as Kansas was, Metropolis is as far away from Kansas. The shift in production design is immediate and impactful: there are no vistas or lone figures in windswept fields, the streets of Metropolis are skyscraper canyons and the offices of the Daily Planet crowded and buzz with life. Lois Lane’s first line is “How many ‘t’s in ‘bloodletting?'”

Superman: Superman: The Movie part 2

So Jor-El sends his son Kal-El to Earth because his planet, Krypton, is destroyed. Yesterday I was talking about how Krypton doesn’t seem to be that great a place, and it occurs to me that, if Superman is an immigrant allegory and a krypto-Jew, then Krypton is Poland and Jor-El’s clan are Jews among Poles: outcasts even among their own people. Or, rather, they are what David Mamet calls “our Jews,” part of the Kryptonian establishment but not really considered true Kryptonians and mistrusted when the going gets rough.

In any case, Jor-El sends his son away from the icy sterility of Krypton and into Kansas, the breadbasket of America and the place Dorothy was so sick of. So the people who find Kal-El’s set-adrift basket in the rushes are not high-level Egyptians in the capital of the state, but precisely no one from nowhere, Ma and Pa Kent from Smallville, “the people” mentioned at the top of the US constitution and the least Jewish people in America’s least-Jewish state.

At the end of Tarantino’s superlative Kill Bill, we finally meet the titular Bill, and the first thing he does is regale us with his opinion of Superman. Superman, he says, is the only superhero who puts on a disguise when he’s not saving the world. Superman is his real identity, says Bill, Clark Kent is his opinion of what an Earth-man is: clumsy, oafish, meek, skittish, terrified of girls. Tarantino is one of our greatest living directors, but in this he is dead wrong: Superman is Clark Kent, and that’s his defining characteristic. Born a god, he is raised as a human, a Kansan no less, which makes him more human than most people. The answer to “Why doesn’t Superman just take over the world?” is: because his parents raised him to be polite. The brilliant graphic novel Red Son asks “What if Superman had landed in the Soviet Union instead of Kansas?” because yes, Superman may be from Krypton, but he is not a Kryptonian, he is a nice young man from Smallville. Yes, his homeland was destroyed, but his homeland wasn’t even a homeland to his own family – Kansas is the only home he’s ever known.

Superman: Superman: The Movie part 1

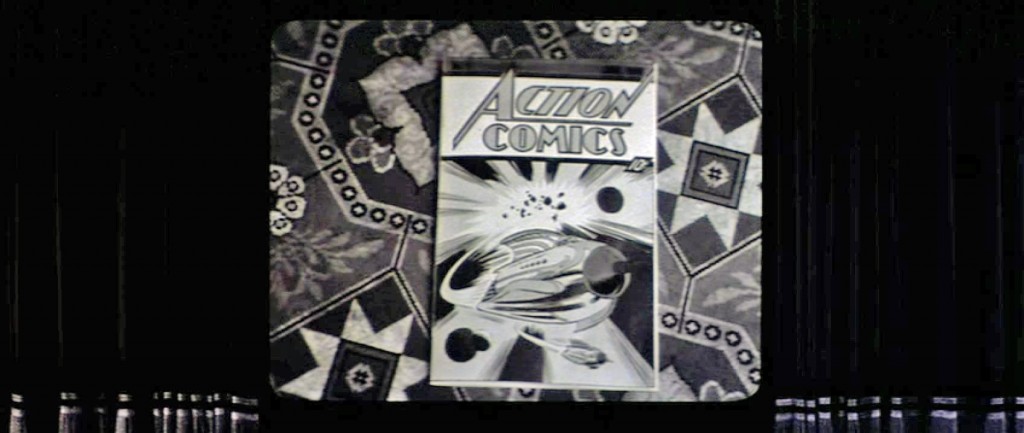

The thing to remember about Superman: The Movie is that it was the first of its kind. Made in 1978 by middle-aged men, it was poised between nostalgia and hipness, gravity and camp, cutting-edge verisimilitude and old-fashioned Hollywood spectacle. It wants to take its subject matter seriously, but can’t quite commit to it fully.

I was 17 when it came out, and theoretically its target audience. The advertising, John Williams score and space-bound title sequence made it clear that it was going after the Star Wars audience, which included children who didn’t know about Buck Rogers serials and nostalgic grownups who did. Having never read the comics, my concept of Superman in 1978 was limited to the syndicated reruns of the George Reeves show from the 1950s (which had borrowed heavily from the radio shows of the 1940s). The stunning Fleischer Superman shorts were a long-gone artifact at that point, not yet available at the counters of every drugstore in America. Only one, “Superman and the Mechanical Monsters,” had been shown to American audiences in recent decades, in the 1977 Fantastic Animation Festival, which was, in and of itself, a cultural touchstone in the pre-cable days of American geekdom.

The George Reeves show never went to Krypton or dwelled on Superman’s tragic backstory (much as the 1966 Batman show never once mentioned why Bruce Wayne dresses up as a bat to fight crime), so the idea of a movie presenting, with grandeur, “serious” actors, a large budget and state-of-the-art special effects (that look laughably terrible today) was breaking new ground for a viewer like me. And the first couple of acts really hammered home the weighty mythology and came to form the idea of Superman in the minds of my generation.

So the movie opens with a shot of curtains opening to reveal a 1930s movie screen, with standard 1:33 aspect ratio. The curtains, in an of themselves, were significant in 1978 because that was the moment that multiplexes were exploding, and curtains in movie theaters were becoming a thing of the past. The curtains in the movie palace were there to remind the audience of the ritual of the theater, of the glamour that awaited the audience on the other side of those curtains – the multiplex did away with glamour and ritual. They turned moviegoing into a transaction, not a passport to adventure. By opening with a shot of curtains, black-and-white curtains at that, the movie seeks to frame its presentation in a sense of tradition, of promises made and kept.

(The theater where I saw Superman was, in fact, a converted vaudeville house from the 1920s, complete with stage, dressing rooms, orchestra pit and fake “Spanish Piazza” decor. When the curtains opened to reveal a movie that begins with curtains opening, it made the moment doubly somber.)

Batman: The Dark Knight Rises part 15

So, in eleven minutes, Gotham City is going to blow up. A lot can happen in eleven minutes, in a movie, when a nuclear explosion is imminent.

First, we have Blake leading the orphans (and some other citizens) on an exodus out of the city. Depending on where they are in relationship to the bomb, they’ll all die in the explosion regardless of whether they get across the bridge or not, but let’s say that somehow crossing the bridge will magically get them out of harm’s way. Blake gets them halfway across the bridge and runs into another police force (Newark?), whose job it is to keep people from trying to escape (for the public good). As at the top of the sequence, it’s a confrontation between civilians and police, but the positions are reversed. No civilians were in the fight against Bane’s army, because they’re all here with Blake confronting another police force. (The police, don’t forget, are the “thin blue line” separating civilians from criminals — it’s their job to confront thugs, they’re urban warriors. It’s appropriate that the police don’t enlist civilian aide in their attack on Bane’s HQ, just as it seem garishly inappropriate for a police force to threaten to fire upon civilians whose only crime is to wish to escape a nuclear blast.)

Batman: The Dark Knight Rises part 14

As The Dark Knight Rises heads into its final long, sustained suspense-action sequence, it pauses to give a moment of truth to Foley, its most lily-livered character. Foley, who, just yesterday, was seen scurrying into the darkness of his home to avoid confrontation, is now leading an army of cops (freed by Blake and Batman) into an all-out assault on Bane’s headquarters. It seems that, after all, Gordon and Blake have finally inspired Foley, even Foley, to action, to take back his city. For, the question rises, to whom does a city belong? It belongs to its citizens. The Bruce Waynes of the world may think it belongs to themselves, and the politicians may think it belongs to themselves, but a city without citizens is nothing — society is the responsibility of everyone.

Bane’s forces, bless their hearts, give the cops warning before firing. How odd, that they have rules of engagement at this point, against men they entombed months earlier! The beat is meant, of course, to show the complete inversion of roles: the police are now the brave dissidents heading into confrontation with the now de facto criminal police state, ensconced in the corridors of power, complete with Attic Revival Greek temple style white-stone columned buildings. Whatever his pretensions, Bane is the new boss, same as the old boss, but with sharper fangs.