Mindhunter vs One Neck

Watching the new Netflix show Mindhunter, I am reminded how the concept of “serial murder” was brand spanking new when I was a teenager, that killers like Ted Bundy, John Wayne Gacy, Jeffrey Dahmer and the rest were a terrifying new phenomenon to law-enforcement agencies, who had no vocabulary or protocol to deal with them. A novel like The Silence of the Lambs was capturing events that were still in the headlines, the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit being a weird experimental new idea in an FBI where Dillinger-hunter J. Edgar Hoover’s death was still a fresh memory. Suddenly the FBI went from gangbusting to psychology, which required men like the protagonists of Mindhunter to travel around interviewing serial killers, to try to understand how their crimes were possible.

When I sat down to write the play One Neck, I read a whole stack of books on serial murder, and none — not one — came close to a clear explanation for their subject matter. For a researcher, the quest to understand involves trying to get inside the mind of a sociopath, which puts one in a very strange, very dangerous mental place (which the show Mindhunter explores to an extent). I can still remember trying to capture the voice of “my” killer, Lucian, writing for months in my room in Brooklyn, and how, in order to achieve his voice, I had to abandon every scrap of what I knew about morality. I would spend nights writing, hunched over my Royal portable typewriter, and then venture out in the morning to go to work and the world would seem like a very strange place.

That was just from reading those books and struggling to write that character, I can’t imagine what it was like for the FBI agents and psychologists who were actually in the room with those murderers.

There has been exactly one good movie about serial murder, one that captures what it’s like to struggle with a mind like that, and that’s David Fincher’s Zodiac (Fincher is a producer on Mindhunter, and directed the first two episodes). There is one great play about it, and that’s Lee Blessing’s Down the Road, which is about a “true-crime” writing couple who decide to take on the job of interviewing a serial killer for a book and how those interviews destroy their marriage. When I saw a reading of Down the Road in the early 90s, I said “That’s it. That’s what it’s like.”

My play One Neck isn’t about about that obsession or the (thankfully temporary) damage it did to my psyche. Rather it’s about what happens when a piece of chaos crashes a dinner party in Long Island, a party starring the peak of western civilization: a scientist, a stock broker, a TV news producer, a painter and a lawyer. While it’s almost been a movie a number of times, the play is deliberately anti-dramatic. The first act is a comedy of manners, the second act is pure existential horror. (As I liked to say in rehearsals, the first act is The Man Who Came to Dinner, the second act is Endgame). The narrative invites the audience in the same way the killer does, by being funny, weird, honest and discomforting. Then, when it’s got your interest piqued, it goes in for the kill.

The Venture Bros “Maybe No Go” part 2

As part 2 of “Maybe No Go” begins, The Monarch and 21 fight with, and turn the tables on, Redusa, who, we learn, isn’t even a member-in-good-standing with the Guild. She’s an outlier and an obvious has-been, but she’s still in line before the Monarch to arch Rusty. As 21 points out, the Monarch could “legally” kill her, but instead they let her off with a shrunken head, and, as mentioned before, a collectable free pen just for signing the waiver. As one of the few beats of actual supervillain action in the episode (the big set piece is still to come), it’s notable that the Monarch does very little in the scene but grouse and intimidate; 21 does all the heavy lifting of thwarting and threatening.

The Venture Bros “Maybe No Go” part 1

One of the most potent themes of The Venture Bros involves the question of the value of popular culture. Is it worthless garbage manufactured by corporations to distract people from the horrors those same corporations inflict daily upon the world, or is it a kind of magic, or both, or neither? The show might be a kind of a family saga, but it is also very much about the entertainment that reaches us when we are children. That entertainment, the shows and comics and commercials that hook us when we’re young, for better or worse, informs who we are as adults. It contains lessons about life, but also trains us to be consumers. I don’t think any episode of Venture Bros addresses that aspect of the theme better than “Maybe No Go.”

Out in the desert, the A-story of the episode begins with Billy Quizboy and Pete White experimenting with putting mouthwash in cookie dough (presumably for a cookie recipe). This experiment is taking place in their ancient trailer, under the broken neon sign advertising their company Conjectural Technologies. Obviously, business has been slow since the Ventures moved to New York, and no worthwhile inventions are coming down the pike.

Into this threadbare idyll comes a Truckasaurus operated by Augustus St. Cloud, the creepy collector of classic pop-culture memorabilia who has taken it upon himself to arch Billy Quizboy. “To the Quiz-Cave!” exclaims Billy, and we next see the opening titles to what I take to be an imaginary kids’ show starring Billy and Pete “The Pink Pilgrim,” done in the Hanna-Barbera style of the 1960s. The question is, if the show is imaginary, who is imagining it? My guess is Billy, who has lived too long in the shadow of Rusty Venture, who, even though he’s miserable because of it, once had his own TV show when he was a child. In taking on St. Cloud as an arch, Billy is, in his own way, getting out from under Rusty’s shadow and “getting his own show.” The entertainment of Billy’s childhood got into his system so completely, he’s willing to risk everything for a chance to join the party, as it were, and become his own super-science crime-fighter.

His fantasy is involved enough that, the next time we see him, he and Pete and their robot assistant are in the aforementioned Quiz-Cave, in their super-hero costumes, struggling to defeat the Truckasaurus attacking their trailer. The interesting thing about the scene, and the “Quiz-Cave,” is that, unlike, say, Batman and Robin going to the Batcave, where they analyze clues and hop in the Batmobile, the Quiz-Cave is entirely defensive in its effect. Even in his fantasies as an adventurer, Billy’s tendencies are inward.

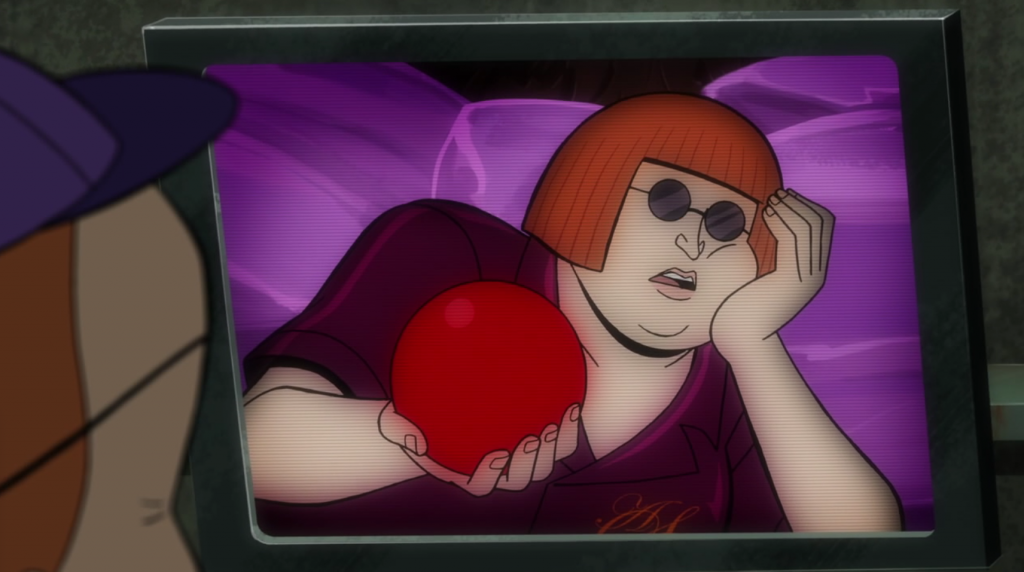

The Truckasaurus, it turns out, is a mere distraction. Under this noisy cover, St. Cloud has stolen from Billy and Pete what appears to be a red rubber ball. Only a red rubber ball, but to Billy and Pete it’s “the holiest of holies” and “the source of all our powers.” The question of what exactly this ball is and what is its worth becomes the linchpin of the A-story.

The Venture Bros: “Hostile Makeover” part 2

Brock’s reappearance as the Ventures’ bodyguard very much indicates a fresh start for the series. And yet no fresh start in the Venture-verse is without casualties. In this case, Brock’s reinstatement means reassignment for Sgt. Hatred. A nobler character would take the change in stride, but Sgt. Hatred is not a nobler character, and the sight gag alone of the cut between Brock, above, and Hatred, below, is indicative enough of the two men’s characters: Brock is cocksure, respectful and upright, and Hatred is hunched, defeated and whining. He not only doesn’t take the setback easily, he refuses to take it at all, and stays on as the Venture’s unassigned stalker-bodyguard, sneaking around the Venture building and spying on the other security forces, looking for errors, echoing the more comic tension between HELPeR and the J-bots.

(On a more meta level, how cruel is this world, where Hunter S. Thompson is still alive in a cartoon, but David Bowie is not?)

The Venture Bros: “Hostile Makeover” part 1

It is a new season of The Venture Bros, and so it is time to once again ask “What does Rusty want?” “Hostile Makeover” answers the question before the titles even begin. Rusty wants his dead brother’s money, and receives it. Having outlived both his distant father and his parasitic twin, Rusty, who has lived in the past for so long, now has a new fortune to squander, and a new place to squander it in. Having been trapped since childhood in the dark, backward 1970s-Hanna-Barbera-netherworld of the Venture Compound, Rusty now has his own high-rise building smack on Columbus Circle in up-to-the-minute New York City. Now, perhaps, we can see him age in a 2010s-era Manhattan penthouse as his shiny new surroundings gradually get old and then burnish into nostalgia.

“Too Many Cooks:” an analysis

If you have access to the internet, and I think it’s safe to assume you do, chances are you’re already familiar with “Too Many Cooks,” Caspar Kelly’s surreal, head-spinning take on the tropes of television. This 11-minute short, produced for Adult Swim, goes so far beyond simple labels like “parody” and “satire” that it warrants some special consideration. Once you’ve seen a form-shattering piece like this, you start to ask “Why aren’t more things like this?” All the year’s best movies — The Grand Budapest Hotel, Guardians of the Galaxy and Birdman, for starters — bend the shapes of their forms, but “Too Many Cooks” rips its form to shreds, then crams it into a Cuisinart. Hit the jump to begin your journey into madness.

Breaking Bad and the importance of plot

As Breaking Bad draws to its close, internet folk have deployed millions of pixels to dissect its meanings. All of which attention the show richly deserves. However, I haven’t yet seen an article describing what the show has meant to me, and to writing for television, so I’m going to write it now.

The Venture Bros: “The Devil’s Grip” part 2

The Monarch finally has his prey, Dr. Venture, where he wants him. After much deliberation over a long list of choices, he decides to use “the bell.” Unfortunately, Rusty is, apparently, partly deaf due to years spent on his father’s jet. Meant to be used as a marital aid, he instead becomes a cockblock.

The Venture Bros: “The Devil’s Grip” part 1

“The Devil’s Grip” has four major protagonists: Sgt Hatred, Col Gentleman, the Action Man, and The Monarch. Two of these characters are decidedly minor in the Venture universe, another is an arch turned guardian and the last is a straight-up villain, the villain of the series. Their stories are intertwined in this episode around the theme of “regret.” Hatred regrets giving up his job as guardian, but is then moved to rescue Dr. Venture by his default-setting of “soldier.” The Action Man regrets not living a more square life and is moved to action by the presence of Hank in his life, Col Gentleman just plain regrets, and The Monarch starts at a place of ultimate power (for him) and slowly slides toward regret. Regret, in this episode, leads to nostalgia, a form of homesickness, and leads in all cases to comings home. “The Return Home,” in all cases, is not presented as a retreat but as a gesture of healing, a symptom of wisdom, a reassessment of each characters’ place in the universe.

The Venture Bros: “Bot Seeks Bot” part 2

Brock’s mission is now “to save Ghost Robot,” which seems big of him, considering that he doesn’t seem that attached to Ghost Robot, considering that no one seems that attached to Ghost Robot, really. Brock’s passion here is for his work, his job, the job for which he has forsaken his family, the Venture clan, for SPHINX, which has been destroyed by his foster father figure, Hunter Gathers. Brock’s job is his family, and it’s the only thing he’s good at. He can’t win at love, he’s backed away from being a father, he’s distant with his work brothers (he even steals one’s wife), but his job is everything to him, an all-or-nothing proposition, even when “the job” is nothing more than invading a nightclub to rescue a robot from an awkward date.