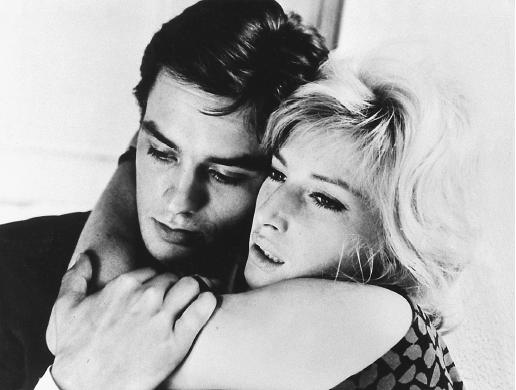

Movie Night With Urbaniak: L’Eclisse

YOUR ATTENTION, PLEASE: This post was originally at least twice as long. Somewhere in the posting of it, half of it got mysteriously eaten by some livejournal program glitch. This makes me angry, but I currently don’t have the time or energy to re-write it. Suffice to say, I liked this movie and so did

.

[beginning of original post]

You know how I mentioned last time around how L’Avventura has no plot, yet is still tremendously exciting? Well, L’Eclisse has even less plot than L’Avventura, and is even more exciting. It’s almost like Antonioni is daring himself to stretch this method of designing narratives as far as it will go.

[significant portion of post mysteriously eaten here.]

[description of first 50 minutes of the movie — Vittoria’s difficulty with relationships, her restlessness, her discomfort, her flight to Verona]

[we join the post half-way through — I am describing a rather amazing 10-minute scene set in the buzz and flurry of a bad day at the stock exchange]

Urbaniak says, “the best extra work of all time.” I mean, it’s really quite stunning, it’s a hugely complicated scene, certainly as complicated as, say, any Hitchcock suspense scene, and as exciting, but like I say, it’s even more of an impressive stunt because we have no idea what it has to do with anything.

Anyway, Vittoria’s mother is there at the stock market, as usual, but today she’s really upset because she’s losing all her money. The market takes a downturn and stays there and everyone is quite upset by the end of the day. And Vittoria shows up toward the end of the day, wondering what all the excitement’s about. She knows nothing about the market and less about crashes (“But if someone lost the money, then surely someone else had to get that money — right?” she asks, hopefully).

10. Piero points out to her a man who has lost 50 million lira in the day’s trading, a sad, overweight, bespectacled man who wanders silently out of the marketplace, and I say “it would be great if the movie now just suddenly dropped everything and followed that guy around,” which, much to my amazement, it then proceeds to do, for about five minutes. Vittoria follows him as wanders, a little shell-shocked, around Rome, much like we’ve watched Vittoria wander shell-shocked, only we know the reason for this guy’s discomfort. But it seems Vittoria sees a kindred spirit in this man who’s lost everything and doesn’t quite know how that happened. She tails him to a little cafe, where he sits down and busies himself with a pencil and paper. We think maybe he’s writing a suicide note or a letter of resignation, but when Vittoria (and we) finally see the paper, it’s covered with childish, even girlish, drawings of little flowers.

11. Vittoria takes Piero to her mother’s apartment for some reason, I don’t know why. She barely knows him, only that he’s her mother’s stockbroker (and her mother now owes him quite a lot of money). We see the room where Vittoria grew up and learn that her father died in the war and her mother is terrified of poverty. As is everyone, quips Piero, but Vittoria says that she never thinks about it. Or being rich either. And we realize that Vittoria doesn’t seem to have given much thought to anything in her future at all — she just kind of blindly gropes forward, hoping the next thing that comes along won’t be quite as much of a dead end as the last thing. She flirts with Piero, then shies away, then flirts with him again. Mom comes home, worrying about where she’s going to get the money to pay Piero — she’s already hocked all her jewelry.

12. At Piero’s office, Piero’s boss tries to explain to the workers how they’re going to get through the crisis of the next stock cycle, how it’s vital to get the money lost from the deadbeats who’ve lost it. Piero needs no coaching on this — he’s regular monster when it comes to making investors feel like losers and idiots for trusting him with their money. And like I say, suddenly we’re seeing everything from Piero’s point of view instead of Vittoria’s. And while Vittoria is vaguely unhappy and fidgety and uncomfortable with everything, Piero is a callous heel who doesn’t seem to have a thought in his head beyond eating and drinking and screwing and doing business — which is to say he’s a stockbroker.

13. After work, Piero, at a loose end, drives over to Vittoria’s place and woos her beneath her balcony (aha! So the Romeo and Juliet reference was intentional!). Why is he attracted to her? Does it have something to do with her mother owing him a great deal of money? More to the point, what does she see in him? Anything? Or is this just how she is with men, just kind of wandering in and out of relationships, not really knowing what she’s doing there, not really having the will to break away? While Piero’s chatting her up, a friendly drunk steals Piero’s pricey sports car and drives it away. This bothers Piero, but not enough to stop him from trying to get a leg over with Vittoria.

14. Next thing we know, the drunk (I think) has crashed Piero’s car and it’s getting fished out of the river. Vittoria is a little horrified by this, but Piero is only concerned about whether or not it will greatly affect the car’s resale value. Everything in the audience’s will screams for Vittoria to go far away from this cad, but she spends the afternoon wandering around the suburbs with him anyway, strolling past a number of rapidly piling up symbols — baby carriages, priests, a recurring horse-drawn cart, and most important, a half-finished new building and the stacks of construction materials surrounding it, which get treated to many disconcerting, lingering closeups.

Vittoria grabs a balloon off a baby carriage, then sends it aloft to her not-very-good friend Marta’s balcony. Marta, the daughter of the big-game hunter, obliges her by getting her father’s elephant gun and blowing the balloon into atoms.

As Vittoria tries to decide to let Piero have his way with her, she rather strangely plunges a chunk of wood into a rain barrel on the new building’s construction site. It’s an odd moment, but it gets odder still, as we will see.

15. Later that night, Vittoria calls up Piero but then doesn’t say anything when he answers.

16. Several times before the end of the movie, we cut back to that chunk of wood in the rain barrel. I don’t know why, but apparently the chunk of wood means something. Is it Vittoria’s soul? Are we checking to see that her soul is remaining afloat? Or is it hope that floats? In any case, the chunk of wood starts to take on significant emotional significance. We want to shout out “go chunk of wood! float! float! float!”

17. Vittoria allows Piero to take her up to his place. Piero is just as big a heel in his own apartment as he is in public. Even though he grew up in this apartment, he has no connection to anything there and seems to have no inner life. He’s decorated the place in cheap bachelor-pad decor and keeps his supply of nudie novelty pens in the study. To underline the metaphor succinctly, he offers Vittoria a chocolate from a box, but when he opens it he finds that the box is, in fact, empty.

Vittoria and Piero fidget around in this apartment, trying to figure out how to start this love affair the two of them apparently want to have, not knowing quite how to do it. The sequence is almost as long as, and serves as a bookend to, the first scene with Riccardo — there, Vittoria was stumblingly trying to figure out how to leave a guy, here she’s trying to stumblingly figure out how to get together with one. “Around you I feel like I’m in a foreign country,” she says, and we know exactly what she means. To make his point succinctly, Antonioni has their first kiss happen through a pane of glass.

The tag line for Annie Hall was “A nervous love story,” but that fits L’Eclisse even better. Both of these beautiful young people are absurdly nervous about something — love or “the world” or something, I don’t think they know. I think Antonioni knows, but I don’t think he wants to tell us — that would somehow ruin everything.

They apparently finally get it on, and Vittoria, for a moment or so, seems happy. Why, we don’t know.

18. Then — crisis! The rain barrel leaks, spilling its water into the street and down the gutter. The camera lingers on this for a long time, the water gushing out of the rusted barrel, Vittoria’s special chunk of wood, her stick of hope, swirling around helplessly as water level drops.

19. Then, as a denouement, some buildings, some faceless people wandering around the cold, modernist, characterless suburb, and a curtain call of symbols. The baby carriage again, the priest, the horse and carriage. A sprinkler is shut off. A modernist streetlamp comes on. There’s that building again, with its heaps of unused construction materials. A man gets off a bus carrying a newspaper — the headline is something like “ARMS RACE SHOWDOWN” and “A NUCLEAR SHADOW,” which almost ruins the whole movie. It’s like Da Vinci writing at the bottom of the Mona Lisa, “She’s smiling because Italy has justemerged from a thousand years of church-dominated ignorance.” Does the H-bomb account for Vittoria’s discomfort, for Piero’s callousness, for the stock-market crash? Is that what the movie is finally “about?” Or is the nuclear threat only a symptom of something else, something harder to put one’s finger on? Because these answers are harder to come to, ultimately I think L’Eclisse is a more daring and accomplished movie than L’Avventura — Antonioni here really seems to be on the verge of something profound. This is tough, unsentimental, rigorous, hugely disciplined filmmaking, with the highest of artistic aspirations — no wonder the purists are so upset by Blow-Up, which is stylish, superficial and glib in comparison.

In the closing moments of the movie, a jet plane flies overhead. The sound-effect geek in me cannot help but note that the “jet plane” sound used is the exact same recording heard a few years later at the beginning of The Beatles’ recording “Back in the USSR.” Coincidence or incredibly-obscure homage? You be the judge.

Movie Night With Urbaniak: L’Avventura

The first thing you need to know about L’Avventura is that it has no plot. The second thing you need to know about L’Avventura is that, in spite of having no plot, it is still tremendously exciting.

I don’t know how it manages to do that.

This was a rare instance of

actually requesting a movie to watch, rather than the two of us just kind of pawing through my DVD collection until we find something we both want to watch. He showed up with the movie clutched in his slender, spidery, indie-stalwart hands, still it its shrinkwrap, still with the price tag from Amoeba on it.

The movie is loaded with symbolism, but the characters aren’t symbolic — they’re real people. At least I think they are. Every time I tried to read the movie as purely symbolist it would answer with a scene that said that it was actually a character study.

Come to think of it, the story structure kind of reminds me of Raymond Carver. It’s not about big moments, or about a coherent dramatic arc. It’s about these people caught in a situation and it kind of sits there and studies how the people behave. And all the incidents that make up the narrative are all really small and not necessarily significant in and of themselves, but are so specific, and so ineffably cliche-free, they retain our interest. We keep watching partly because we want to know why the people are doing the things they’re doing and partly because we want to know why the filmmakers chose to shoot the scene. What do all these little moments of behavior add up to? Will the trashy celebrity who shows up in Act III show up again in Act IV? Why this town, why this church, why this shirt, why this room, why this hour of the day? Resonances and echoes show up all over the place (just like they show up in that scene with the church bells) and every time you think a scene isn’t going anywhere the scene goes somewhere, but never where you thought it was going.

In other ways, the story structure reminds me of Kubrick, in that there are long slabs of narrative dedicated to illustrating one plot point and we don’t know what the plot point is until we arrive at it at the end of the slab. Those slabs are, roughly:

1. Let’s go on a cruise! (30 min)

2. Looking for Anna (30 min)

3. Will Sandro get a leg over? Will Claudia give in? (30 min)

4. Claudia commits (30 min)

5. Crisis (17 min)

1. So there’s this woman, Anna. She’s young and Italian in 1960. She was probably a child during the war. Her father is a builder of some sort. We first see her have a halting conversation with dad in front of one of his building projects. He’s tearing down some old buildings to put a new one there.

says that’s a major theme of the movie: destroying down the old to make way for, what, exactly? The anxiety of that question hangs over the entire narrative.

Anna’s in love with Sandro. Or maybe she isn’t. Claudia is in love with Anna. Or maybe she’s in love with Sandro. In any case, there’s a lot of unspoken tension between the three of them. Maybe Anna isn’t really happy with Sandro and would rather go with Claudia. Maybe the opposite is the case.

This bunch of funsters go on a cruise in the Mediterranean with some friends. Their friends’ relationships are, to put it mildly, dysfunctional at best and doomed at worst.

Theyarrive at an island. Folks go swimming, folks climb on rocks, folks bicker.

2. Somebody notices Anna isn’t around any more. The group searches the island. They call the police. The police and whatever authorities do things like this search the island. For 30 minutes we watch people climb over rocks and gaze into the water and wonder what the hell happened to Anna. Because either she’s hiding, which is unlikely, or she’s unconscious somewhere we haven’t looked yet, or she’s dead somewhere we haven’t looked yet, or she got on a boat we didn’t see and rode off somewhere. If she’s dead, she could be dead by suicide or by murder or by accident.

3. Apparently Anna is not on the island and nowhere near the island. The other couples go on with their vacation while Claudia worries about Anna and Sandro half-heartedly searches a nearby town. I say half-heartedly because, well, for some reason Sandro, now that Anna is gone, doesn’t want to waste the opportunity to make a move on Claudia. Claudia is horrified by Sandro’s advances — her friend-girlfriend -Sandro’s-girlfriend is missing and she feels guilty and terrible about it — this is no time to be messing around the ancient, tumble-down towns of rural Italy.

The narrative starts to splinter here as Sandro gets distracted and Claudia gets anxious. Sandro runs into that trashy celebrity mentioned above, Claudia gets caught at a society gathering refereeing for her non-friend Giulia’s (or is it Patrizia’s?) makeout-session with a Bob Denver-lookalike teenage artist, whose paintings are an affront not just to the beauty of the villa where he’s staying but an affront to their subjects and to the act of painting itself.

4. Claudia suddenly, and without preamble, gives in to Sandro’s advances and declares herself desperately in love with him. Maybe she’s been in love with him from the beginning, maybe she’s just recently decided she is, maybe she’s fooling herself. We know Sandro is a lout who has no idea what love is, that seems clear enough, but Claudia seems to be cut from different cloth. First, she’s the only one on Team Ennui who wasn’t born wealthy, second she’s the only one who carried any sense of guilt about Anna’s disappearance all the way through Act III. This is where I started to think L’Avventura is about postwar Italy, how a new generation chose to move ahead into some ill-defined bright tomorrow while others couldn’t help but feel a sense of guilt and loss for what had been destroyed in the war. In any case, loss, the careless destruction of the old and beautiful, the replacement of the old and beautiful with the new and ugly (and profitable) is one of the movie’s ongoing concerns.

griped toward the beginning of the movie that he didn’t like the actor playing Sandro, that he was uninteresting and shallow, giving a kind of generic “60s leading man” performance. By the end of the movie he had changed his tune, realizing that the actor was not giving a shallow performance, he was performing the action of being shallow, which is a completely different thing. That is, it’s not the actor who is giving a generic “60s leading man” performance, it is Sandro who is giving it. As Act IV goes on and Sandro starts to reveal his true ugliness, shallowness and restlessness he becomes infinitely more interesting. Conversely, Claudia, once she gives up on honoring Anna and gives in to Sandro’s indelicate advances, becomes slightly less interesting as she pines and swoons and tries on different outfits.

Why does Claudia fall for Sandro? We don’t want her to. If she always had a thingfor him, she’s an idiot, and she doesn’t seem to be an idiot. I prefer to think that both Sandro and Claudia had a thing for Anna and when Anna vanished she created a kind of relationship black hole that sucked Claudia and Sandro toward each other. Claudia becomes attracted to Sandro because they now have something in common — missing Anna.

Let’s say for the moment that Anna is a symbol for something really pretentious like “the soul of Italy.” The soul of Italy has vanished and only Claudia seems to really care about any of that. Sandro doesn’t care — he made his peace a long time ago that he wasn’t going to create anything beautiful. He had his chance — he coulda been a contender architect, we learn at one point, but gave it up for the short-end money. Then we see him knock a bottle of ink over onto a drawing someone’s making of a gorgeous church window. Sandro cares about the soul of Italy insofar as he wishes to destroy it as quickly as possible. To replace it with what? Well, that’s where Sandro’s anxiety comes in. He doesn’t have any idea what he’s going to replace it with. Maybe that’s why he makes such a fast move for Claudia — he’s just reaching out for the nearest available object to replace the hole in his soul that opened up when Anna disappeared.

5. Sandro and Claudia, having declared their undying love for each other, check into a hotel where their friends are staying. There’s a big party going on. Claudia is tired and wants to stay in the room, but Sandro gets duded up in his tuxedo to check out the action. Claudia can’t sleep and mopes around the room while Sandro wanders, bored and restless, among the empty suits and fashionable gowns. He sits down to watch a TV show in the hotel TV room. We don’t see what’s on TV, but it seems to be a show primarily about things that go “WHOOOSH!” He watches this scintillating program for a few seconds before wincing at it and moving on.

Claudia suddenly has a vision that Anna has returned, which she feels would be really bad at this point because it means that her love with Sandro would be doomed. She rushes downstairs to the empty ruined ballroom and finds Sandro making out with the trashy celebrity from Act III.

Claudia dashes out of the hotel, as one does in situations like this, and Sandro chases after her. (The trashy celebrity begs Sandro for a “souvenier” and he disgustedly throws a wad of money at her. She lazily gathers it up with her bare feet like an octopus capturing its prey.)

Sandro collapses on a bench and cries. Does he feel something? Is he worried about losing Claudia? Is he mourning Anna? Is he mourning his own soullessness?

Claudia approaches. A satisfying ending would be: she hits him with a big rock and screams “I KILLED ANNA AND ATE THE BODY, YOU FOOL!” But that’s not what happens. She should, at the very least, be very angry at him — he went pouncing off after Paris Hilton mere moments after declaring his unending love for Claudia — and did so while Claudi was right upstairs! But we watch as she balances that anger for a moment, as she literally balances her own self, gripping the back of the bench to keep herself upright. Then she places a hand on Sandro’s shoulder, as though to forgive him, then, incredibly, she moves her hand up to his head, to pull him to her, to comfort him. We have no idea what happened to Anna, all we know is she’s gone and, as far as the movie is concerned, isn’t coming back.

(Idea for sequel: L’Avventura II: Anna’s Return!)

And then the last shot, reproduced above. Half mountain, half ruined building, the wounded, conflicted, embattled couple facing their uncertain future. “The ‘adventure,'” says

, is the couple’s adventure into adulthood.” “And Italy’s adventure into the future,” I add, half-heartedly, because I’m really not sure.

Another long, awkward elevator ride

INT. ELEVATOR — NIGHT

Ingmar Bergman and Michaelangelo Antonioni ride in (what else) silence.

IB. Mm.

MA. You with the whole “is there a God” thing, me with the whole “existential angst” thing —

IB. Mm.

MA. And here we are.

IB. Here we are.

Silence.

MA. What was it finally did it to you?

IB. Mm?

MA. ‘Cos we both got up there, man, you know? 80s, 90s, I mean, that’s a load of years for a couple of guys who made such a big deal out of how miserable life is.

IB. Mm.

MA. Me? That Chuck and Larry movie. I saw that, I just said “forget it, I’ve had enough, I’m out of here.” Billy Madison was cute, but I drew the line on Sandler with The Waterboy. What about you?

IB. Me, oh, you know me. The weight of a Godless world, the the suffocating oppression of memory, the haunting terrors of family.

MA. I gotcha, sure.

IB. And Transformers.

MA. Ooh, yeah, that one hurt.

IB. I’m like, “what, I expanded the vocabulary of cinema to explore the most important, penetrating questions of the human condition so that monster robots could fight each other?” Give me a break.

MA. I totally get you.

Silence.

IB. By the way, I’ve always wanted to tell you —

MA. Yes?

IB. I hated Zabriskie Point.

MA. Oh yeah? Well I hated The Serpent’s Egg.

IB. You —

Silence.

IB. Ah, the hell with it.

Silence.

MA. Jesus, this is one long elevator ride, isn’t it?

IB. You ain’t kidding.

MA. Did you, when you got on, did you happen to notice which way it was heading?

IB. Well, I assumed —

Pause. They look at each other.

The elevator dings. The doors slide open. Bergman and Antonioni go to step out, but TOM SNYDER steps in.

TS. Hey, Ingmar Bergman! Michaelangelo Antonioni! Good to see you!

He slaps them on the back. They look distinctly uncomfortable.

TS. Boy, this death thing, this is wild, isn’t it? I tell you, I wasn’t ready for this one. Reminds me of the time I was taking a train to Bridgeport once, I was in the station, and you know how they’ve got those newsstands, right? Where they sell all the newspapers and candy and whatnot. And there’s a shoe-shine guy next to the newsstand, right? And I’ve always wondered about the shoe-shine guy. You know? Who is this guy? Is this what he wanted to do with his life? “Shoe-shine guy?” Has he reached the pinnacle of his career? “I am a shoe-shine guy?” And he’s got this hat, it’s kind of like a conductor’s cap, almost like maybe a conductor gave it to him, like you know, maybe this guy’s a little “simple,” you know, and one of the train conductors took pity on him and gave him a hat, you know, to cheer him up, make him feel like he’s part of the team. Anyway, so I’m there in the train station and this skycap goes by, huge stack of luggage on one of those rolling things, what are those things called, dollies? Not dollies, but like a dolly, with the handle, you know? And I’ve always wondered, who decides whether the cart gets a handle or not? And —

Bergman and Antonioni wither as Snyder chats on and on. Fade out.