Oscar Dead Pool

Oscar prediction has become far too easy — at least around my house anyway. I just ask Mrs. James

, who hardly ever sees any of the movies and is always 100% accurate in her predictions. (Her technique: “I just pick the one that seems most obvious.”)

(My prediction for this year: Alvin and the Chipmunks in a walk.)

So the only real excitement in the Oscar-cast comes from guessing who will be the last celebrity mentioned on the Celebrity Death Roll three-quarters of the way through the show.

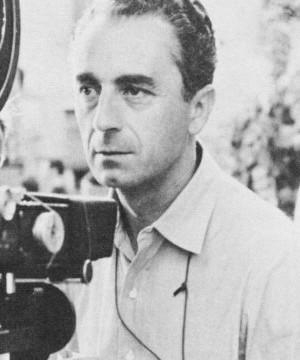

Here, we have three top-rank, obvious choices. Ingmar Bergman is the greatest director of all time, but Deborah Kerr is a genuine old-time movie star, and an American to boot. Will Antonioni take away some of Bergman’s heat by being another world-class foreign-film director, who died on the same day as Bergman?

Will Jane Wyman prove a spoiler to Kerr, since she was, after all, once married to Ronald Reagan? If so, what if they cancel each other out, allowing Anna Nicole Smith to squeak past?

Or will Jack Valenti wield his extraordinary influence, even from beyond the grave, and take all?

Will Kurt Vonnegut and Norman Mailer be mentioned? Plenty of movies (mostly bad) were made from their novels. If so, which will be mentioned first? If they’re mentioned, does thatmean they have to include Ira Levin, or for that matter Sidney Sheldon?

Will Merv Griffin make the list, and what about Toms Snyder and Poston? Or will they lump Tom Poston together with Charles Nelson Reilly and Kitty Carlisle Hart in a kind of “game show trifecta” moment?

I assume that Brad Delp (singer for Boston) and Eric von Schmidt (folk singer) won’t be mentioned, but what about Luciano Pavorotti? He made a movie once.

Or will the Academy, in a bow to the younger set, include the lolrus?

As for me, my money is on Dick Wilson, who, through his indelible portrayal of a haunted grocery-store manager with a unique fetish, taught a generation of Americans about the importance of squeezable toilet paper.

Cute kids update

SAM (6): I was wearing my Fancy-Schmancy Ultra Limited Edition Secret Stash In-house Promo Venture Bros shirt today, which attracted Sam’s interest.

SAM: Who’s that?

DAD: This? This is — [dramatic voice] — The Monarch!

(no response)

DAD: He’s a bad guy.

SAM: I can see that!

Meanwhile, KIT (4), has taken it upon herself to put together a new lineup of The Beatles:

To those who believe that Ringo is irreplaceable, here is your answer: Ringo is replaceable, if he is replaced with BATMAN FROM THE FUTURE and A SHARK ON A POSTAL DELIVERY TRUCK.

Bush on the Plame affair:

“And if there is a leak out of my administration, I want to know who it is. And if the person has violated law, the person will be taken care of. … I don’t know of anybody in my administration who leaked classified information. If somebody did leak classified information, I’d like to know it, and we’ll take the appropriate action.”

And yet, gosh, it turns out: Bush Authorized Plamegate Leak

Bush on the assassination of Benazir Bhutto:

“The United States strongly condemns this cowardly act by murderous extremists who are trying to undermine Pakistan’s democracy. Those who committed this crime must be brought to justice.”

And we have learned by now that the only possible way to discern truth from the mouth of Bush is to take what he says and state it in the exact opposite.

(So the above quote could be translated as: “I strongly applaud this brave act by life-loving centrists who are trying to sustain Pakistan’s brutal dictatorship. Those who committed this great deed must be made exempt from the rule of law.”)

Only possible conclusion: Bush ordered the assassination of Bhutto.

(Well, at least he got the “murderous extremists” part right — that’s the most succinct description of his administration I’ve read yet.)

In a Lonely Place

Bogart with a beautiful woman, Barton with a mosquito — sounds about right.

What says Christmas better than a dark, sweaty noir about a has-been Hollywood screenwriter who may or may not be a vicious killer?

I don’t know what forces prevented me from watching Nicholas Ray’s 1950 masterpiece of paranoia, heartache and broken dreams, but I’m glad I finally got around to it. And about two-thirds of the way through, it struck me that In a Lonely Place would make a smashing double feature with the Coen Bros’ Barton Fink.

The parallels between the two movies are too many to be mere coincidence. In some cases, the Coens have kept elements of Ray’s movie intact, in other cases they’ve ingeniously inverted them.

Both Dix and Barton consider themselves superior beings in the Dostoyevskian sense, and their sense of superiority gets each of them into drunken brawls. Dix fights with six or seven different guys over the course of Lonely, while Barton confines his brawling to one USO dance. Both Dix and Barton have drunken has-been friends: Dix has his “thespian” pal Charlie Waterman, the kind of actor who goes around intoning Shakespeare in plummy tones while wearing a top coat and carrying a cane, Barton has the Faulkneresque W.P. Mayhew.

And both land in trouble with the police. In Lonely, Dix is too depressed to read the novel he’s supposed to adapt, so he asks a hat-check girl who’s read it to come over to his house and tell him the story. Similarly, Barton Fink, desperate for inspiration, calls Mayhew’s secretary, lover and de facto ghostwriter Audrey Taylor to come over to his place to help him prepare for his pitch meeting. In each case, the poor woman winds up dead, the victim of a brutal murder — Lonely makes its killing the inciting incident while Barton, in true Coen form, makes its murder the end-of-second-act twist. And, in each case, it’s not necessarily clear that the screenwriter is entirely innocent of the murder.

In each movie, the murder of the woman is, largely, beside the point of the story. In Lonely it’s a jumping-off point for the filmmakers to examine the precepts, dreams and flaws of Hollywood; Barton does all that and then goes someplace much stranger. It both expands upon the themes of Lonely, pulling in World War II and the Holocaust, but also makes the story more intimate, burrowing inside Barton’s head, so to speak. In each case, the screenwriters’ struggles with their unworkable screenplays are given much more weight than any murder investigation.

In a final inversion, the producers in the two movies have wildly different reactions to the screenwriters’ final efforts. I’d say more but it would be telling.

Lonely is also, of course, a love story, which, I’dhave to say, Barton is not. It’s a very unhappy love story, which I suppose any movie about a screenwriter in Hollywood would have to be. Dix meets and falls in love with Laurel, the woman who lives across the courtyard from him, partly because she provides an alibi for his whereabouts during the murder. Later, we find that she provided the alibi as an excuse to get to know Dix. This, for me, immediately threw suspicion on Laurel as the killer: no intelligent actress in Hollywood would think she could advance her career by making a pass at a screenwriter.

For more on Barton Fink, I direct you to this analysis. (I can’t believe I didn’t get the fire/water symbolism — it’s not like it’s not referenced in practically every scene.)

A Cricpmist Story

My son Sam (6) has a gesture that’s difficult to describe. It’s a head-shake, a guffaw and an eye-roll that indicate “okay Dad, whatever you say.” He uses it when I’ve spoken something that sounds completely outlandish to him, but he can’t figure out why I’ve told him such a fish story. For the sake of moving forward, I’m going to call this gesture The Sheesh.

For instance, this gem from the other day:

DAD: Today is the Winter Solstice, it’s the shortest day of the year, and the longest night. Did you notice how early the sun went down today? It’s because it’s the Winter Solstice. Today the sun went down earlier than yesterday, by just a couple of minutes, and tomorrow it will go down a little later, by just a couple of minutes. And those minutes will build up and up until we get to the Summer Solstice, which is the day that has the most daytime and the least night-time.

SAM: Is there a Spring Solstice?

DAD: No, but there’s a Vernal Equinox and an Autumn Equinox, and those are the two days in the year when the daytime and the nighttime are exactly the same length.

SAM: (The Sheesh)

(Sam brings home a document he’s written at school. Dad reads it. It contains the word “CRICPMIST.”)

DAD: What’s this word?

SAM: Christmas!

DAD: Ah. And the second “c,” that’s like a French “c,” I get it.

SAM: Right, and there’s a “p” in it. Like a “crisp mist.”

DAD: Right. Right. I like it. Like a crisp mist, that’s great.

SAM: Isn’t that how you spell it?

DAD: Er, well let’s work through this for a second. (pause) Has anyone ever told you about the story of Jesus?

(Sam looks confused)

DAD: Okay, that’s fine. Here’s the deal: about 2000 years ago, this baby was born, named Jesus. And the idea was that this Jesus kid was the Only Son of God. And this Only Son of God thing, people called it “The Christ.”

(Dad writes down the word “Christ” on the back of an envelope)

DAD: And later, churches, you know when people go to church and they pray and sing songs and stuff, that’s called a “mass.”

(Dad writes down the word “mass” next to the word “Christ.”)

DAD: So people who thought that this Jesus kid was the Only Son of God, they would have a special celebration on this day called “Christ Mass,” and eventually that just got shortened to “Christmas.” I’ll tell you though, I would feel a whole heck of a lot better celebrating a crisp mist than I would celebrating the birth of the Only Son of God. That sounds like my idea of a real holiday.

SAM: So, seriously, what does God look like?

DAD: What does God look like? Well dude, I’ve heard a lot of different ideas about what God looks like, and I honestly haven’t heard any better ideas than “God looks like Mace Windu.”

SAM: Yeah, but really, what does he really look like.

DAD: Well dude, nobody knows what God looks like. The important thing you have to know is that no matter what anybody says, nobody anywhere has any idea what God looks like. If someone says they know, they’re lying to you. Now then, since the idea is that God created the entire universe, one could say that God looks like everything, and maybe looks like nothing.

SAM: But what does that mean “God looks like everything?” You mean God looks like a plug, and a pen, and a radiator?

DAD: That’s exactly what it means,dude, it means that God looks like a plug and a pen and a radiator. But don’t forget, you’re leaving out a lot of stuff, like trees and the sky and the ocean and fish and stuff. In fact, there’s a story in the Bible where God shows himself to a guy, and you know what he looks like?

SAM: What.

DAD: A bush.

SAM: (laughing out loud) “A bush!”

DAD: It’s true!

SAM: So, like, I could tell a story about God talking to me and God could look like a lamp.

DAD: You could absolutely tell a story about God talking to you and God could look like a lamp.

SAM: (does The Sheesh.)

_____

In any case, Merry Cricpmist from What Does The Protagonist Want.

Coen Bros: The Man Who Wasn’t There

UPDATE: You know, I almost forgot — The Man Who Wasn’t There was shot on color stock which was then desaturated to achieve some of the most lustrous black-and-white photography in cinema history. However, because of the demands of the marketplace, in some markets the movie was released in color. For those who wonder what The Man Who Wasn’t There looks like in color, the answer can be found here.

_____

So I’m reading the new biography of Charles Schulz. Schulz, like Bob Dylan and the Coen Bros, was from Minnesota. Like Dylan and the Coen Bros, Schulz consistently, throughout his life, downplayed the cultural significance of his work. Bob Dylan says “I’m just a song and dance man,” the Coens say “O Brother is a simple hick comedy,” and Charles Schulz, to the end of his days, rued the smallness of his ambition, bemoaning the fact that he spent fifty years doing nothing more than drawing a simple comic strip.

Just as Dylan and the Coens have, occasionally, seen fit to acknowledge that yeah, they’re pretty proud of some of their work, Schulz, when pressed, would reveal that he thought of himself as a serious artist doing better work than any of his contemporaries in his field (which, in fact, he was).

Dylan, it is well known, is obsessed with identity and masks, and the Coens have proven to be impenetrable in their interviews. Schulz, as well, said that he wore his unassuming looks as a kind of mask — he always knew he was better than anyone around him, but craved invisibility, anonymity, lest anyone take too much notice of him.

(And then there’s Prince, another Minnesota oddball, who seems to not have gotten the memo about Minnesotans being reserved and self-effacing.)

Schulz’s father, and Charlie Brown’s, as every schoolchild knows, was a barber.

Schulz haunts The Man Who Wasn’t There. The movie is set in Santa Rosa, CA, where Schulz eventually made his permanent home, and set in the late 1940s, when Schulz was developing his comic strip, and was made in 2000, right after Schulz’s death. It takes place in a context of postwar anomie and uncertainty, a mine-ridden landscape of paranoia, depression and sublimated, frustrated desire, just as Peanuts does. Schulz, like Ed Crane (the movie’s protagonist), harbors a bleak, pessimistic grudge against the bulk of humanity, one he keeps well hidden. Like Peanuts, the movie occasionally bursts the bounds of its form and becomes weird, philosophical and unapologetically poetic. It also features, of all things, a young pianist who plays Beethoven. Maybe this is all coincidence, maybe not, maybe it’s, as I say, something in the water of Minnesota, but if there were a character in The Man Who Wasn’t There who owns a beagle I would probably jump out of my skin.

If Ed Crane, “the barber,” is Charles Schulz’s father, that would make his wife’s unborn child Schulz himself, a child never given a chance to live in a world too filled with sadness to give him love. Thing is, Schulz would probably recognize that judgment as a sober assessment of his life.

(It might also make the unborn child “the man who wasn’t there,” since he was not allowed to live.)

In any case, enough of that.

THE LITTLE MAN: In this, the least-ironic of all Coen movies (until recently, that is), Ed Crane is a barber who wants to become a dry cleaner. He’s not a three-time loser after a bag of money, or a brilliant young man with a vision, or a desperate man one step ahead of the law. He’s an ordinary man with a perfectly drab ambition. Yet even this tiny little hope for a better life ends up destroying his world, ruining the lives of everyone he knows.

Why does Ed Crane want to become a dry cleaner? As in most Coen movies, it is shown that the ordinary working man is little more than a sheep whose life is spent being prepared for slaughter by the greater forces of capital. “I’m the barber,” says Ed, in a tone of voice that implies that “the barber” is synonymous with “nobody” (Freddie Riedenschneider echoes this sentiment at another point in the movie).

In the Coen world, there simply is no such thing as an honest living. Anyone with money is a fraud, a criminal or insane. Big Dave Brewster seems to be rich, but he’s not, he’s living on his wife’s money. Freddie Riedenschneider has money, but he’s a lawyer, and a fraud on top of it. And they all bow down the The Bank, the institution that patiently stands by, a pillar of the community, waiting for misfortune to strike its citizens so it can accept the assets handed over to it in times of crisis.

So Ed wants to become a dry cleaner because, in his mind, it’s a way to get his head above the rat race. The man he’s investing with, Creighton Tolliver, even assures him that he won’t have to do any work to make money off the business — the perfect American dream, having just enough capital to start a business that someone else will run, while you sit idly by, collecting money from the suckers. He wants to get his head up above the rat race, but, as we see, those who stick their heads up, the tallest poppies, get their heads blown off. That’s how harsh the worldview of The Man Who Wasn’t There is: even a barber who wishes only to become a dry-cleaner is guilty of hubris, and must be destroyed by the powers-that-be.

Where is there hope in The Man Who Wasn’t There? Ed seeks value in Art, the intangible something that seems to suggest that beauty and balance and the sublime are possible — and he is told, forcefully, to seek value elsewhere. Walter Abundas, Ed’s lawyer friend, seeks solace in the study of genealogy — he finds comfort in roots, in people long dead. And that’s about all Man offers in terms of hope. Big Dave eats and smokes and brags and embezzles, Doris drinks and smokes and reads magazines, her brother Frank doesn’t seem to have brain in his head, Freddie Riedenschneider lies and eats, and Creighton Tolliver wants only to start a business. (It turns out, against all odds, that Tolliver is not a fraud — he’s just one more guy who stuck his head up and got it shot off.)

(It’s also worth noting that classical music, which symbolizes “Art” for this movie, is also used as a force of crass capitalism, as Freddie Riedenschneider is seen preparing for his court appearance in the “Turandot Suite” of his hotel and stuffing his face at a restaurant called Da Vinci’s — so much for art supplying life with beauty and meaning.)

There is also a tender, convincing love story at the center of The Man Who Wasn’t There. Ed is married to Doris, although he can’t really think of a good reason why, and decides to exploit his marriage for capital gain. The results of his attempt are disastrous, but as the movie goes on, we see Ed, in his own quiet way, finally fall in love with his wife. There is no love scene more sweet and honestly felt in the Coen cannon than the one where Ed confesses the murder of Big Dave to Freddie Riedenschneider and the two of them trade sad, loving glances across the table, as though Doris is finally seeing Ed for the first time and liking what she sees. If Doris could speak in that scene, I think she would say something like “Ed, I never knew — if you had told me you were capable of blackmail and murder, I think I could have loved you.”

Because the one thing that Ed and Doris share is their contempt for humanity. Doris is capable of expressing hers, Ed is not. Doris can get drunk and curse out her family, or tell a pesky salesman to fuck off, or laugh in the face of a murder accusation. Ed is capable of little besides a tiny nod of his head, but his dread and hatred of people is palpable.

CRIME AND PUNISHMENT: The police in The Man Who Wasn’t There are interesting. They are not thugs, brutes or clowns, as they are in other Coen movies. What they are are, to a man, self-loathing. They gripe about pulling shit detail, they get depressed about having to break bad news, they mope and drink and sigh and curse.

If the noirs of Chandler and Cain took place against the backdrop of World War II, with the detectives representing stand-ins for American soldiers, the noir of Man has a specifically postwar bent, with those same soldiers feeling guilty and ashamed of the actions they were required to take against the enemy. The Japanese theater of the war is explicitly invoked several times in Man, as well as Nagasaki. To a large extent, the euphoria of America’s victory in WWII gave way quickly to a sense of guilt and dishonor, since we knew that, on some level, we had cheated to win and, in the process, had ushered into the world a horror a thousand times worse than a sneak attack on a military base in Hawaii.

(Strangely, Barton Fink takes place at the time of Pearl Harbor, in Los Angeles no less, but alludes only to the Germans and Italians — conversely, Man talks only about the war against Japan and does not mention Germany or Italy at all [unless you count the Italians Doris is related to].)

(And, for the record, Charles Schulz fought in WWII, but in Europe, not the Pacific.)

The anxiety the US felt about the atom age became expressed in tales of UFO sightings, a fact Man expresses with great comic skill and no small amount of poetry. In a way, you could say that Man is about 1949 — it’s almost as though the Coens decided on a date, then looked at an almanac of “things prevalent in 1949,” then wrote a plot based on that list. Postwar anxiety — check, dry-cleaning — check, UFO fever — check, the rise of men’s magazines — check, the postwar boom in classical music — check.

HAIR: Ed worries a lot about hair. What is it, where does it come from, why does it grow, how does it relate to the possibility of a soul? In a brilliant move of philosophical jiu-jitsu, Ed reasons that, if hair keeps growing after the body dies, “the soul” is the thing that keeps it growing, and when the soul dies, then the hair stops. Otherwise, why would it keep growing? Of course, he answers his own question, in another scene, while thinking about dry-cleaning: “chemicals,” he intones, and the single word wraps up the totality of mid-20th-century discomfort — where are we going, what have we done, what does anything mean any more?

(As a side note, let me mention that Ed shaves Doris’s leg as he plans the scheme that will end in her death — likewise, his leg is shaved by a prison employee as he goes to the electric chair.)

THE MELTING POT: Race is always important in a Coen movie, yet in Man the issue becomes cloudy. Ed seems pretty WASPy, that seems clear enough, but he’s married to Doris, who is played by Frances McDormand, who is not Italian, yet she is the sister of Frank, who is played by Michael Badalucco, who very much is Italian, and Doris even goes out of her way to insult her family as “wops.” Is she supposed to be Italian, or adopted, or what? Likewise, Big Dave is played by the manifestly Italian James Gandofini, yet his name is Dave Brewster, which indicates that perhaps he has changed it, as many Italians did in the US, the better to improve their circumstances, to get their heads out of the rat race. In contrast, “Guzzi,” the long-dead originator of the barber shop where Ed and Frank work, is an example of the Italian immigrant who didn’t change his name, and thus was “the barber,” relegated to a lifetime of anonymous irrelevance. Likewise, Creighton Tolliver is played by the unabashedly Italian Jon Polito, another example of an immigrant seeking a higher station in life through a change of names. Likewise, the “Frenchman” who teaches piano in San Francisco is played by Adam Alexi-Malle, who is Spanish, Italian and Sienese — but not French. Freddie Riedenschneider, for his part, is a typical Coenesque Jew, and is played by Lebanese actor (and fellow Midwesterner) Tony Shaloub.

FAVORITE MOMENT: Freddie Riedenschneider cannot be sure of the name of the man who devised the Uncertainty Principle. He also totally misrepresents it — which is fine, since his interpretation matches most laypersons understanding of the concept.

_____

The Man Who Wasn’t There is one of the Coens’ most straightforward, honest and heartfelt movies — no wonder it bombed. They stuck their heads up and got them blown off.

What they’ve done, in a way, is expose the subtext of noir — if noir was about wartime stress and postwar anxiety dressed up in the language of lies and betrayals, then Man states those themes explicitly. Freddie Riedenschneider points to Ed and calls him “Modern Man,” and I honestly think the Coens, with that speech, indulge in a rare moment of hand-tipping. I think they really mean for Ed to be a symbol of Modern Man, and they are very serious about his quiet search for beauty and meaning in a hollow world of talkers.