Day For Night

A French film crew shoots a romantic melodrama at a studio in Nice. Would make a nice double feature with CQ.

Words that I jotted down while watching:

crackling

deft

joyous

fascinating

multilayered

Altmanesque

It’s shaming to see Truffaut so utterly in command of his tools while playing a director who constantly feels like he’s a failure and a fraud. The ensemble work here is wonderful. The narrative steps in and out of realism, scenes go from strict behavioralism to coy, affectionate commentary in the blink of an eye, the pace never drops a beat and Truffaut makes it all seem easy.

Late in the movie, Truffaut laments that movies like the one he’s shooting are a thing of the past, that there will never be big, fake studio pictures any more, that movies will from 1973 on will be shot in the street with non-actors. I don’t know what he was thinking, but one of the sweet, sad things about watching this movie now is realizing that, to a large extent, the techniques being employed here, seen from the age of digital sets, digital backgrounds and digital actors, are as quaint today as a movie set during the time of silent film would have seemed to Truffaut.

CQ

A charming, intricate, compulsively watchable, rather brilliant comedy by Roman Coppola, his first and, to date, only feature.

A young, experimental filmmaker in 1969 Paris is suddenly handed the reins of an unfinished sci-fi sex comedy. As he grapples with his daunting new assignment, he also deals with his fractured love life, his stunted artistic ambitions and his decaying family.

It perfectly captures a moment in film history when the possibilities of film as a language seemed unlimited. As the young man tussles with the problems of his film and life, the mysteries, pleasures, seductions and promises of the art form open to him and allow him to lose and find himself. That the movie pulls all this off while remaining funny, fast, original, unpretentious and fizzy is something like a minor miracle.

Jeremy Davies, it-boy of the modern independent film movement, plays the young filmmaker, and Gerard Depardieu and Giancarlo Giannini are on hand to remind us of the moment that the film encapsulates.

If the movie finally falls short of its revolutionary promises (“Astonish me!” is the producer’s note to the untested director, while an older director insists that film has the power to change the world), well, then it reflects well the time it’s describing. But it also shows the joys and sadness of the art of film, and how the most malleable, most complex, most powerful of artistic tools is consistently put in the service of silliness.

RKO 281

Orson Welles incurs the wrath of William Randolph Hearst when he makes Citizen Kane. An important story about the collision of art and commerce, told in a brisk, enjoyable, coherent, straight-ahead fashion.

In the manner of most TV movies, it is overlit, overacted, oversimplfied and over-explained. In the manner of most biographical dramas, compression renders complex relationships into two-line exchanges, scenes where Famous People trade Statements instead of human beings conversing. The characters almost wear name tags and plot points are telegraphed far in advance. John Logan, who wrote the screenplay, went on to write many very good scripts, including the similar The Aviator, which gets the Famous Person Biography genre with much more panache, grace and detail.

The presence of Brenda Blethyn reminds me of Topsy-Turvy, Mike Leigh’s film about Gilbert and Sullivan, which is my personal high-water mark for biographical drama of this sort. In that film, a premium is placed on observation and behavioralism; one picks up the plot as the film goes along. Here (and, honestly, in most biographical drama) the viewer is constantly reminded who everyone is and what their relationships are. Or as David Mamet puts it, people are always saying “Come in, because I am the King of France.” The drama is presented instead of inferred; the audience does little work, there are no dots to connect.

The cast is an extraordinary collection of very good actors, but sadly, whenever a group like this is assembled to play Famous, Charismatic People from the Past, all they can really do is demonstrate how we don’t have titans like that in our culture any more.

Liev Schreiber, one of my favorite actors working today, can only hint at the towering presence and commanding force that Welles possessed. I can hardly blame him; the last time I saw Welles depicted on film, it took both Vincent D’onofrio and Maurice LaMarche working together to pull it off. (It’s funny how, in yesterday’s query for films about filmmakers, Welles comes up so often, and always in such tragic terms.)

One thing that RKO 281 does that I wasn’t expecting was to make a human being out of William Randolph Hearst, and it brings up an idea that fascinates me: how does it feel to be the subject of a brilliant artist’s scathing portrait? How does it feel to be portrayed as a soulless monster by an artist with full command of his tools, to know that, no matter what else you accomplished, you will always be remembered as “that guy from Citizen Kane?” How does it feel to be the guy in Alanis Morrissette’s “You Oughta Know?” How does it feel (sorry) to be the subject of “Like a Rolling Stone?” It doesn’t matter what “your side” of the story is, the other side has already been told too well, no one would ever believe you, or care to listen. The subject is defenseless.

Ironcially enough, it’s largely through the craft and brilliance of Citizen Kane that anyone bothers to think about William Randolph Hearst at all these days. Also ironic is that, as much as Hearst must have hated the film, that Welles, in fact, endowed him with more pathos and sympathy than he probably deserved.

Contest!*

Favorite movies about people making movies. Preferably, though not necessarily, comedies.

For example: 8 1/2, Living in Oblivion, Day For Night.

Hulk

A number of extremely talented people worked to try to make this the best movie possible. It’s hugely ambitious and has a complex, elaborate editing scheme. I liked it a lot better than I did when I saw it in the theater.

I wish I had a better understanding of exactly what the hell is going on in it.

This paragraph from A.O. Scott’s review in the New York Times sums up my feelings regarding the plot:

“I’m far from an expert in such matters, but I would have thought that a combination of nanomeds and gamma radiation would be sufficient to make a nerdy researcher burst out of his clothes, turn green and start smashing things. I have now learned that this will occur only if there is a pre-existing genetic anomaly compounded by a history of parental abuse and repressed memories. This would be a fascinating paper in The New England Journal of Medicine, but it makes a supremely irritating — and borderline nonsensical — premise for a movie.”

And I also agree with this paragraph:

“All of this takes a very long time to explain, usually in choked-up, half-whispered dialogue or by means of flashbacks inside flashbacks. Themes and emotions that should stand out in relief are muddied and cancel one another out, so that no central crisis or relationship emerges.”

The tone sways wildly from ponderous to outrageously campy, sometimes in the same scene. At one moment a father and daughter discuss the unpredictability of the human heart, at the next moment the daughter is attacked by a giant mutated poodle. At one moment the Hulk is smashing tanks and swatting down helicopters, the next moment he’s lounging on a hillside contemplating lichens with a misty, faraway look in his eyes. At one moment a father and son have a colloquy on matters of identity and social order, the next moment Nick Nolte is gnawing on an electrical cable.

There are three bad guys, and none of their plots seem to make any sense. The biggest of them, which gets a very late start at an hour and eighteen minutes into the movie, involves Nick Nolte turning on some kind of machine and huffing on some sort of hose, then turning into some kind of super-being with some kind of super-powers which are visually impressive but which also seem tacked on, forced and incoherent.

There seems to be some kind of battle going on between the creative team and the genre they’re working in. They’ve chosen to make a movie about an enraged green smashing guy, but they also want the movie to be about “deep” themes and ideas. They’ve given their protagonist an inward journey (“Who am I?”) instead of an outward problem (“I’ve got to stop the bad guys”) and so the narrative seems choked, static and listless at just the points where it should be fleet, extravagant and larger-than-life.

Then there’s some problems with the plot. I’ve seen the movie twice now and there’s things I just don’t follow. I think I know why Hulk’s dad tries to kill him but I don’t know why he set off whatever green bomb thing he set off, or what the consequences of the blast were. I know in the comic book, it’s the “gamma blast” that created the Hulk, but here the script takes great pains to explain that the blast had nothing to do with it. Then why is it in the movie?

Then there’s the matter of the General’s daughter. This is a movie about, among other things, intergenerational conflicts, and so in addition to a scientist who has problems with his scientist father, there is a daughter who has problems with her general father. And the plot has to bend itself into a pretzel in order to keep those conflicts afloat, which is too bad because there isn’t much interesting going on in them.

But for the record, here goes: A Long Time Ago, there was this army base, see? And there was this general. And the general had a daughter. And the general was tussling with this scientist, who blew up the base with the Gamma bomb and then ran home to try to murder his son. And then many years later, the son grew up, forgot all about his murderous father, and then became a scientist, where he, by sheer coincidence, began studying in the exact same field as his murderous father, alongside the general’s now-grown-up daughter! This is a plot to make The Comedy of Errors seem like the acme of observational behavioralism.

Then there’s whatever Nick Nolte turns into. It’s pitched as the big battle that the narrative has been leading up to all this time, but it comes off as a late attempt to kick the movie into gear. Nick Nolte argues with his son, bites into an electrical cable, becomes a Big Weird Thing, then flies off, somehow, with The Hulk, to Some Place Far Away where the two of them fight as Nick turns into rocks and water and lightning and ice. Then a jet comes by and drops some kind of Large Bomb on them and somehow that takes care of Nick but also leaves Hulk alive. If anyone has any idea what any of that is supposed to mean, please let me know.

Then there are the special effects, which never quite take off. There are moments of great visual flair and compelling action, although the titular Hulk never really seems to be part of the scene he’s in. That’s okay, I don’t quite buy the special effects in the Spider-Man movies either. The difference, I think, is that the Spider-Man movies are pulp, understand they are pulp and function well as pulp, carrying their cliched truths lightly and with grace, while this movie slows down so often to think about “serious ideas” that it gives you too much time to realize how silly all of it is.

Here’s Looking at You

The first two are from my copy of Time Magazine. The third is the cover of the new Office DVD set.

Why does Steve Carell hate America?

Meanwhile:

I know nothing about this show and I’m sure it’s wonderful, but I crack up every time I see this ad. All I can think is, “There’s something behind Skeet Ulrich, and we don’t know what it is, but it’s apparently more interesting than an atomic blast.”

Venture Bros: Guess Who’s Coming to State Dinner?

“Guess Who’s Coming to State Dinner,” like The Big Lebowski, is about people living in a world where things once meant something but don’t any more. That’s a major theme for Rusty Venture in any given episode of course, but it’s stated pretty boldly across the board here. Just as the burnouts and washups of Lebowski try in vain to scare up some of the glamour and intrigue of the 40s Los Angeles of The Big Sleep, the heroes of “Dinner” all live in the shadow of some greater, more genuine heroism.

Bud Manstrong, who’s been in space for years with a (supposedly) irresistable woman (whose face we never see), feels that his mission and his lack of sexual experience somehow combine to make him a hero. He lives in the shadow of the genuine heroism of the Space Age astronauts and is cursed with a name that recalls both Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong. He has a domineering mother with the hair and pearls of Barbara Bush (but the mouth and drinking habits of Martha Mitchell). His haircut, his “manly man” physique and attitudes, his imagined virtue and rectitude, his humiliation at the hands of Brock, have all collided to make him into quite a quivering sexual ruin.

Rusty complains from the start that Bud is no hero (and who are the “terrorists” responsible for crashing the space station? Could it be that the Guild has actually committed a crime, caused — gasp — an actual death?), and he’s correct, but also wrong at the same time, as he believes the title of “hero” belongs to himself for owning the space station. Of course, he owns it only by default, since he inherited it from his father, just as we have inherited the space program from a previous generation, and have turned it from a stunning, still-incredible symbol of adventure and the American Spirit into a depressing series of milk-runs for the Pentagon.

Vietnam, itself a ruinous war for men who sought to become heroes, is mentioned in passing. Vietnam, of course, has acquired its own heroic myth, that of the brave soldier who has made it through hell. Brock mentions it to Rusty, who, of course, brings up that Brock was too young to have fought in the war. Brock says that he never mentioned fighting in the war, thus reducing Vietnam’s shadow of World War II heroism to a sadder, even more pale charade.

“Phonies!” says Bud’s mother, dismissing all the guests at the table while slipping a hand onto Brock’s thigh. Brock, as usual,is the simplest, least complicated, most comfortable man at the table. Brock is a hero every week, a “real man,” but doesn’t brag or make a big deal of it. Indeed, he often tries to reason with the man he’s about to kill or dismember, stating flatly what’s about to happen and how the other man can avoid a grisly fate. A real hero knows that heroism is often something to be avoided and that discretion is the better part of valor.

But yes, the President is a phony and the head of the Secret Service is a phony (with his masking-tape perimeter and his priceless halting line-reading regarding same). The old cleaning woman seems genuine, and of course “saves the day” in the end, proving that heroism can often be found in simple wisdom and household common sense.

“Dinner” borrows the plot of The Manchurian Candidate, and just bringing it up shows how far we have fallen from the Space Age. The original was, and still is, a subversive, mind-blowing, utterly original movie. Its remake, while not without merit, can’t hope to hold a candle to the brilliant, unnerving Cold War masterpiece.

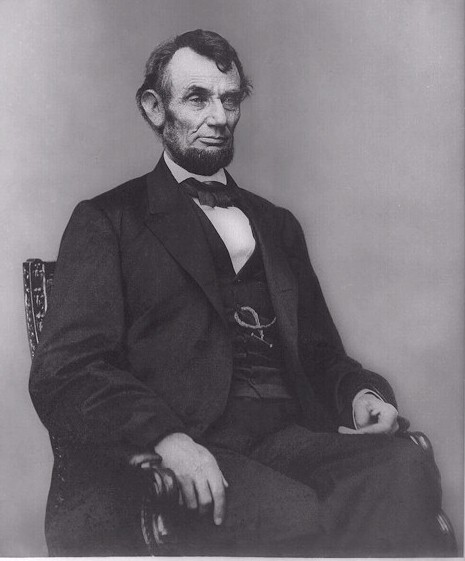

Who else is a true hero in this episode? Well, Dean as usual tries, although he’s beset with Hank’s taunting and his own almost total lack of education. It’s one thing for a pair of teenage boys to be unfamiliar with The Manchurian Candidate, but to be unfamiliar with the career of Abraham Lincoln is something else.

Lincoln, one of the greatest presidents who ever lived (another, Roosevelt, gets Lincoln’s approval), also steps forward as a true hero, although he is saddled with the dimwitted boys, allegations of homosexuality and his own limited ghostly powers. Even in the face of crisis and failure (he, after all, saves the wrong man and for the wrong reason and is shot in the head for the second time in his existence), he retains his good humor, elegance and panache. Maybe it’s impossible to be a true hero in these times, but it’s at least possible to attain grace and keep your sense of perspective.

(Lincoln’s plan for saving the president, by the way, represents the most imaginative and yet prosaic method of “throwing money at the problem” I’ve ever seen dramatized.)

As Manstrong is unmasked as an unheroic, twitching masturbator he exclaims “My God, it’s full of stars!” Which is, of course is a reference to 2001: A Space Oddessey, the ultimate Space Age cultural triumph, and another shameful reminder of how far our culture has fallen.

The chip in the back of Manstrong’s head turns out to be a massive red herring. Given the episode’s theme it could hardly be otherwise. The question remains, however, why? Why is the chip in the back of his head? Did he put it there? Did the doctors? Or was it part of the accident, too close to the nerve to remove, just another random occurence in a rudderless world?

Idiocracy

This movie hit me with a force I was quite unprepared for. I have little intelligent to say about it at the moment (ironically enough), but I’d like to do my part to get people to see it.

Once in a great while, a movie has a vision so thorough and detailed that it alters the way the world outside the theater looks. The last time it happened to me was Batman in 1989; after two hours steeped in Tim Burton’s vision of Gotham City, with its corruption and decay and facsist architecture, I couldn’t walk the streets of New York that summer without half-expecting to see the Batwing fly overhead.

It happened again tonight with this movie. The basic concept (people are loud and stupid) couldn’t be more simple, and yet this movie takes it to such a relentlessly high degree that it becomes difficult to shake off. Idiocracy is a vision of America so specific, so obvious and yet so unique and so detailed, it was impossible for me to walk out of the theater without hearing people talking in its language, moving to its rhythms and acting according to its principles.

I’m not even sure what to compare it to. Structurally it reminds me of Sleeper; both movies put a self-described “average guy” into a dystopian future, and neither movie has a well-engineered plot. But after that I start to run out of points of comparison. If Clockwork Orange had been conceived of as a comedy, I suppose it might have turned out something like this, but that’s about it. Suffice to say, it’s not like Beavis and Butt-head and it’s not like King of the Hill and it’s not like Office Space. In fact I would say it’s like nothing you’ve ever seen before, and how many movies can you say that about these days?

Venture Bros: Fallen Arches

Often I will watch an episode of Venture Bros more than once to catch the asides and subtexts; this is the first time I had to watch it twice just to sort out all the plot strands.

In your typical well-written 22-minute TV episode, there will be an “A” story and a “B” story, ie: Homer quits his job while Lisa works on a science project. Often the two stories will link up towards the end of the episode, but not always.

In “Fallen Arches” I found an “A” story, a “B” story (with its own sub-plot), a “C” story, a “D” story, an “E” story and, incredibly, an “F” story.

The “A” story is: Dr. Orpheus has, for some reason, vaulted from the backwaters of “down-on-his-luck necromancer with no job renting Rusty’s garage” to “leader of superhero team with his own private island.” Apparently he, like Rusty, was once quite the thing, but, like many men, found himself burdened and diminished by marriage, fatherhood and responsibility. Wife gone (why is unclear, although at this point of the show literally anything is possible) and daughter of age, he suddenly “qualifies” for an arch-villain, to be supplied by the Guild of Calamitous Intent. (Why the Guild exists, how it operates, and why Dr. Orpheus suddenly qualifies is unclear, but I’m sure time will tell.) He gathers up the members of his old team, The Order of the Triad, and auditions arch-villains.

The “B” story, I would say, is Rusty and his Walking Eye (glimpsed in the season 1 titles, it now has its own plot-line). He’s built a useless machine and is bitterly frustrated when no one recognizes its brilliance. Rusty also takes time out (because the episode is, apparently, not plot-heavy enough) to chat with Dean about the birds and the bees, a chat that leaves neither one any more enlightened than before.

The “C” story involves the Monarch’s Henchmen and their attempts to, on what apparently is a slow day in Monarch-land, branch out into supervillainy themselves. Comedy ensues.

The “D” story involves a homely prostitute and her sad misadventure at the hands of The Monarch, who, after receiving his pleasure (whatever that is), turns into some kind of Thomas Harris villain on her and forces her to undergo a series of life-threatening tests in order to leave his cocoon. An Edgar Allan Poe quote is thrown in for good measure.

The “E” story involves Hank and Dean solving the Mystery of the Bad Smell in the Bathroom (and the disappearance of Triana).

The “F” story involves Torrid, who looks like a cross between Deadman and Ghost Rider, his misadventure in the bathroom and his attempts to impress Dr. Orpheus and Co., bringing the plot full-circle.

The title is “Fallen Arches” but it could have just as accurately been “False Impressions,” as each character in the episode is trying to impress someone, and often failing. Rusty wants to impress his family with the Walking Eye but fails, so instead tries to impress the Guild creeps auditioning for Dr. Orpheus instead. This works to some degree, but not without Rusty debasing himself with his Whitesnake-music-video/Tawny Kitaen “washing the car” vamp. And finally Rusty must face the fact that he has impressed no one in his house, that his inventions, his career and his life is a failure, even while Dr. Orpheus is in re-ascendency. The auditioners are desperately trying to impress Dr. Orpheus and company, and mostly desperately failing. The Henchmen want to impress some ideal, invisible female and get nowhere near even failing. The Monarch wants to impress the prostitute and does, in a way, but probably not in the way he’d like to. Dean wants to impress Triana but fails to even get her attention, although he does succeed in impressing Hank, later in the show, with his ability to actually solve a mystery. Finally, Torrid succeeds in impressing Dr. Orpheus by kidnapping his daughter, although how exactly he accomplished that, and how she ended up on Dr. Orpheus’s private island, is left unclear. I’m unfamiliar with Lady Windermere’s Fan but I’m willing to bet its plot revolves around someone trying to impress someone else too.

Who is not trying to impress anyone in this episode? Well, Brock is perfectly comfortable in his skin and doesn’t care about impressing Dean with his abilities to deliver Wilde. He’s just as happy to kill Guild villains in a tux as he was to kill them while naked a few weeks ago. The prostitute doesn’t seem too concerned about impressing the Monarch although she gives it the college try. Dr. Orpheus’s team seems quite self-effacing and comfortable with themselves, and Dr. Orpheus, with his newfound status as superhero, himself seems more confident and relaxed in this episode than ever before. Triana, of course, is a goth chick and so is genetically incapable of trying to impress anyone. Sadly, Dr. Girlfriend is briefly reduced to trying to impress Dr. Orpheus as the hastily-considered Lady Au Pair. It doesn’t take much for her to regain her self-esteem however, Jefferson Twilight’s mention of her deep voice is all it takes.

Any one of these plot lines would have been enough for most shows. This episode had the breathless pace of the Christmas special but was twice as long. It makes me wonder, aloud, what a Venture Bros feature might be like. Could this kind of pace be sustained over 90 minutes? Would there be 18 different plot lines? Would it be like It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, but funny, and short?

The Guild exists, apparently, because all superheroes require an arch-villain. Otherwise how would we know they’re heroes? It wouldn’t surprise me to learn that the Guild is financed by superheroes themselves. My son Sam understands the concept and he can’t even read; he knows that Dr. Octopus fights Spider-Man, Mirror Master fights The Flash and Sinestro fights Green Lantern. When he sees a character he doesn’t know, before he asks “What does he do?” he’ll ask “Who does he fight?”

Reagan understood that every superhero needs an arch-villain, and so does George W. Bush, although Bush made the poor decision to go for the “better Bad-Guy Plot” instead of going after the real villain. The American people have begun to understand that if you’re Superman, you fight Lex Luthor, not the Mad Hatter.