Pop Quiz

What do Samuel Beckett, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Paul Michael Glaser, Rock Hudson, Angie Dickinson, Al Pacino, OJ Simpson, James Garner, Steven Spielberg, Michael Landon, John Houseman, Robert Redford, Oliver Stone, David Lynch, Will Smith and Bryan Singer all have in common?

THE ANSWER:

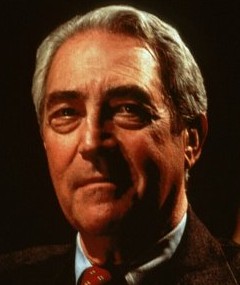

All of them did projects with one of my favorite character actors, James Karen.

With 164 credits to his name, James Karen was a Hey! It’s That Guy! when JT Walsh was still in short pants.

One of his first credits (after episodes of Car 54, Where Are You? and The Defenders) was to appear in Samuel Beckett’s 1965 Film, a baffling whatsit from the soon-to-be Nobel Prize-winning author. Film starred Buster Keaton, and apparently the two of them were good friends, so much so that Karen would go on to impersonate Keaton from time to time. In Film, Karen wears extensive aging makeup that makes him look as old as he is now.

What’s an actor to do after he works with Samuel Beckett and Buster Keaton? Why go on to Frankenstein Meets the Space Monster, of course. Then, after working with a young Arnold Schwarzenegger in Hercules in New York, he got into a groove of television appearances, including Starsky and Hutch, Police Woman, McMillan and Wife and The Rockford Files.

Then came what may have been a breakthrough role in All the President’s Men, where he plays Stephen Collins’ lawyer on a television Redford is watching, and also provides (uncredited) the voice of a slippery politician, the one who protests that he’s got “a wife and a kid and a dog and a cat.” He worked with OJ Simpson in 1978’s Capricorn One, and also in 1979’s The China Syndrome. But the first time I noticed him was in Steven Spielberg’s Poltergeist, where he played Craig T. Nelson’s unscrupulous boss. After appearances on Little House on the Prarie and The Paper Chase, he gave what I consider the greatest of his performances in Return of the Living Dead, where he gets to go completely nuts while battling brain-eating zombies in a mortuary. (One of the amusing things about this performance, for me, was that it was in theaters while Karen was also appearing on television as the Pathmark Drugstores spokesman in New York. I couldn’t watch the commercials, where he is paternal, friendly and blithely reassuring, without thinking of him sweating, turning yellow and trying to eat the brains of some teenagers.) He appears in no fewer than three Oliver Stone movies (Wall Street, Nixon and Any Given Sunday) and also in David Lynch’s Mulholland Dr. Bryan Singer directed him in Superman Returns but then cut his scenes. He remains in the titles but does not appear in the movie, bitterly disappointing at least one filmgoer. Finally, he is featured in Will Smith’s upcoming The Pursuit of Happyness.

I don’t know about you, but that’s what I call a career. And it’s not over yet.

The Squid and the Whale

This is a movie about the dissolution of an American family.

I saw it in the theater when it came out. After it was over, I raced home and started writing a script about the dissolution of my own American family, which dissolved when I was roughly the same age as the older son in this movie.

Watched it again tonight. Now I’m thinking, “Nope, I’m not going to finish that script. Because I can’t write as well as this guy.”

This is simply one of the best written, best directed, best acted American films I think I’ve ever seen. It could not be more straightforward, unfussy, unpretentious. It could not be more naturalistic, better observed, unpredictable.

As a director, Noah Baumbach, like Ozu, has one shot. With Ozu it’s the “camera sitting on the floor” shot, with Baumbach its the “handheld camera” shot. A completely stock effect that you would have thought had run out of steam years ago, but it completely disappears here. In Woody Allen’s Husbands and Wives, you’re constantly thinking “Aha, he’s using a jittery, handheld camera to good effect here,” in The Squid and the Whale you don’t even realize that it’s there.

Why don’t you realize it? Probably because the script is so freaking good. Just really extraordinary. Tiny little scenes of completely normal human behavior, tiny little gestures saying volumes about the characters without ever saying “Hey, did you get what that scene was about?” Beginning toward the end of the scene, so that we have to do a little catchup to figure out what’s going on, having the dialogue be things that people are not saying as well as things they are.

Or maybe it’s because the direction and editing are so good. Unselfconscious jump-cuts remove anything that isn’t important, whip-pans look accidental but then turn out to have a narrative or thematic link to the next scene, the camera stays close to faces but never in a way that says “Hey, this is a movie about faces.” Scenes that would have been milked for their “dramatic import” here are presented as they would have been in real life, meaning, one rarely understands when an “important moment” is happening in one’s life. It happens, and many years later one realizes what the important, life-changing, crossroads moment was. No, scene after scene goes by of crushing importance, but it’s all moving too fast and with too much fidelity to life for something as clumsy as “drama” to enter into the picture. That is, it doesn’t feel like you’re watching a scripted drama at all; it feels like a camera crew followed these four characters around for a few months, shot thousands of hours of film, and then edited it down to this.

Or maybe it’s the acting, which is simply some of the best I’ve ever seen. I’ve always liked Jeff Daniels (who would dislike Jeff Daniels?) but his performance here as a faded, past-his-prime novelist and recently-divorced father is just one of the most astonishing I’ve ever seen. And again, not calling attention to itself. Incredibly detailed, thoughtful, lived-in. I can’t remember a movie where I saw people thinking on screen so much. Laura Linney, who’s always good, is equally mesmerizing as the mother. And then there’s the two teenage boys, Jesse Eisenberg and Owen Kline, who give two of the most detailed adolescent performances I’ve ever seen.

For a movie with no “plot” per se, it crackles with intensity and flies by in a breathless (pun intended, you’ll see what I mean) 81 minutes.

This movie is a miracle.

J.S. Bach: The Early Years of Struggle

“Hey, ‘Mr. Counterpoint’ in there, you want to knock it

off already? You’re giving your mother a headache!”

La Bete Humaine

I pop this DVD in the machine, expecting to see a warm, humanist Renoir comedy/drama like Boudu Saved From Drowning, The Rules of the Game or Grand Illusion. Turns out it’s practically a freakin’ Hitchcock movie.

This is a good thing.

A noir before it had a name (1938), La Bete Humaine is a dark tale of lust and murder set amid the railyards of 1930s Paris. Noir, hell: the plot is practically a chapter from Sin City: there’s a good-looking working-class lug who worries that he might actually be a psychotic killer, a mild-mannered middle-management type who is driven to murder by jealousy and a femme fatale who lures men into murdering each other for her, all the while playing the weak, innocent victim.

Because it’s Renoir, of course, things are more complicated than that. As the guy says in Rules of the Game, “Everyone has their reasons.” You never look at the psycho as anything remotely like a monster, the jealous husband is never belittled or scorned and the femme is both plainly manipulative and sadly victimized.

It’s a real pleasure to watch an artist so effortlessly and confidently in command of his tools. The movie is endlessly suspenseful and surprising while never becoming sensational or italicized. It’s Hitchcock without the devices and the remote coldness.

I’m not overly familiar with Zola, but I’m surprised at how pulpy his sense of plot is. I worked on an adaptation of Therese Raquin a while back, and that book not only has lust and murder and intrigue, but also ghosts and hallucinations and an operatic level of dread. I have no idea what the novel of Bete is like but it sounds like it’s just a notch more highbrow than, say, Jim Thompson.

The notes refer to the plot as a “triangle” (between the lug, the femme and the husband), but I detect a fourth player: Lison, the locomotive that the lug (Jean Gabin) works on. Renoir gives the train a full 7-minute wordless introduction as Gabin guides it thundering down the track, through tunnels and into the station. We see that Gabin has an intimate relationship with the engine, which he underscores later on when someone asks him why he doesn’t have a girlfriend. “Oh, I do have a girlfriend,” he says, “Lison.” (Just the fact that he’s given his locomotive a name, much less a woman’s name, says plenty right there.) Later, when he, without preamble, almost strangles a girlfriend to death on an embankment, the only thing that stops him is a train going by: it’s almost as though he’s in a carnal embrace and interrupted by his “wife” entering the room. He breaks off the strangulation and stomps off, guilty and disgusted with himself. Not that he almost killed a woman but because he feels weak and out of control. (Strangest of all, the woman sympathises with him and they walk off together, finishing their date as though nothing had happened [apparently they’d come to that impasse before].) We get the sense that Lison is a stabilizing force in Gabin’s life, that he lavishes all his affection and labor over this locomotive because if he ever stops working, he’ll have no choice but to murder someone. And indeed, once he does finally murder someone, he turns himself in not to the police but to Lison, as though the locomotive is the only one who can judge him.

Screenwriting 101 — The Bad Guy Plot

I’ve worked on a fair number of superhero/fantasy/espionage/sci-fi/what-have-you projects, and the problem is always The Bad Guy Plot. For some reason it’s always the toughest thing in the script to work out.

To work, to be satisfying, to move with grace and wit and a sufficient amount of danger and threat, The Bad Guy Plot must do ALL the following things:

1. The Bad Guy’s story should be explicitly intertwined with that of the protagonist. Ideally, the inciting incident should influence both. The perfect example would be if, say, the chemical explosion that gives a man superpowers also gives The Bad Guy superpowers but also a severe deformity, making it so that he cannot lead a normal life and thus turns Bad.

2. The Bad Guy’s desire cannot be simply the destruction of the protagonist. The Bad Guy has to have some other goal that has nothing to do with the protagonist (except in the broadest societal sense, ie the hero’s obligation to right wrongs) but which the protagonist must stop. Like, say, most of the James Bond films.

3. The Bad Guy and the protagonist must interact often and throughout the narrative. This is a whole lot harder than it sounds. If the Bad Guy is involved in something Bad and it’s the protagonist’s job to stop him, what usually happens is that the Bad Guy does the Bad Thing in private while the protagonist looks for the Bad Guy, and then there’s a confrontation in Act III.

4. Hardest of all, the Bad Guy’s plan must make sense and follow a logical progression, not only through the narrative but beyond. That is to say, the writer must stop and think "Okay, let’s say Lex Luthor succeeds in growing his new continent and drowning half the world’s population: then what?" This is what I call the "Monday Morning" question. In Mission:Impossible 2, terrorists plan to take over a pharmaceutical company, release a plague, then sell the world the cure. And I’m sitting in the theater thinking "And on Monday Morning, when the pharmaceutical company’s stockholders find out that 51 percent of the corporation is now owned by a terrorist organization, thenwhat?" When Dr. Octopus succeeds in building a working model of his fusion whatsit on the abandoned pier in the East River, after robbing a bank, wrecking a train destroying a number of buildings and endangering the lives of thousands of people, then what?

Keeping all of this in mind, what are your favorite Bad Guy Plots? Which ones have a plot that intertwines with the protagonist’s plot, has a goal that the protagonist, and only the protagonist, can stop, keeps the Bad Guy and the protagonist interacting throughout, and — gasp — makes sense?

I’ll start: Superman II.

Venture Bros: a closer look

![]() mcbrennan posted this lengthy, well-considered analysis of The Venture Bros in response to my entry on last week’s “Victor-Echo-November” episode. I thought it was worth bumping up to a new entry. She starts with quoting a paragraph of mine, then heads straight into the core of the show, which becomes more interesting the more you examine it.

mcbrennan posted this lengthy, well-considered analysis of The Venture Bros in response to my entry on last week’s “Victor-Echo-November” episode. I thought it was worth bumping up to a new entry. She starts with quoting a paragraph of mine, then heads straight into the core of the show, which becomes more interesting the more you examine it.

Take it away, Cait:

“In a way the whole show is about arrested adolescence, with each character presenting their own take on the concept, and that includes Mr. Brisby. Hank and Dean are the most clinical and literal of Team Venture, being seemingly unable to make it out of adolescence alive. Dr. Venture’s more mature self literally made its break from his body to go live on Spider-Skull Island (or is Jonas his less mature self, living his playboy lifestyle?). Phantom Limb may be a sophisticate, dealing in bureaucracy and insurance and masterpieces of Western art, but in a way there’s more than a touch of Felix Unger in him, a fuss-budget who uses his sophistication to hold the world at arm’s length so that he doesn’t have to deal with the messier aspects of adult life, like maintaining a stable relationship or taking responsibility for his actions.”

There’s so much truth to this. I’m not sure if it’s arrested adolescence or just pervasive failure–failure to live up to impossible standards or to fulfil early promise, especially. Whether it’s Rusty’s boy-adventurer pedigree, Billy’s boy-genius, Brock’s football career, or the Monarch’s blueblooded trust fund origins, so many of these characters were destined for greatness and got stuck. Another specific theme I connect with is how the…the knowledge and expertise and talents of all these characters are essentially useless outside their insular little world of adventuring and “cosplay” (or costume business, in deference to the Monarch); the 60s/70s backgrounds and social “rules” are no accident. The world they learned how to live in has passed them by; The idealism of the original Team Venture is as obsolete as Rusty’s speed suits. Brock’s cold war is over; even his mentor has left it all behind, including his gender. The Guild is in league with the police. Faced with the prospect of trying to make normal human connections and fit in with the contemporary world we know (if such a thing even exists for them), Dr. Venture, the Monarch and company instead spend their time riding the carcasses of the dead past, reenacting costume dramas to keep them from going insane with boredom or despair. The scale of their “adventures” is telling: There are no world-changing inventions and no world-domination schemes. And for all the Marvel-inspired costumed supervillains, there arealmost no heroes left, certainly none in costume (outside of that ethically dubious blowhard Richard Impossible, whose entire empire sits on the rubble of Ventures past). I think that’s one of the reasons that Brock in particular can be so emotionally engaging–he’s the heart of the show, trying to hold the universe together as it spins off its axis, protecting the family he loves and trying to safeguard the next generation so that someday, things will be different. He lives by a code of honor, something maybe only the Guild still recognizes. Orpheus plays much the same role for Triana, though she and Kim are more a product of our world, and more able to see the Venture family and their nemesis as anachronisms. Triana feels for the boys, but she won’t end up like them. We hope.

Interesting also that in this world where family is so key, all the mothers are missing (Hank and Dean’s? Rusty and Jonas Jr’s? Triana’s? The Monarch’s? Just for starters…) Interesting also that the strongest female character on the show may or may not have arrived at womanhood through unconventional means, and we certainly know that the man who was like a father to Brock is now more of a mother-figure (of course, the transgender thing may be just a red herring where Dr. Girlfriend is concerned, but leave me my illusions.)

As a more or less failed child prodigy myself, I feel for these characters even as I fear I’m probably going to share their fate. I suppose sitting up at 3am writing a 5000 word essay on a cartoon is not going to change that. 🙂 But the Venture Bros. is of course much more than a cartoon, and I’m not kidding when I say it’s the best show on television. It’s a privilege to live in a time where you get to experience firsthand something that is both great art and great fun in pop culture. There’s so much going on here, so much to think about, that it’s just a delight to watch every week.

Venture Bros: Love Bheits

Random thoughts while tripping through the fragrant copse of tonight’s episode:

*The guy at the beginning of the show, standing on the volcanic landscape, turns to the camera and, for the aide of the illiterate, announces “Underland,” with a gesture as though he were ushering us into a swank restaurant. More establishing shots should be like this. I’d love to see a shot of Central Park, with the Empire State Building in the background, and a title that says “New York City,” and THEN have a guy, a cab driver or homeless guy, come on screen and say “New York City,” with the same kind of maitre-d gesture.

* Just yesterday I was thinking to myself, “I wonder where you would go to get a Slave Leia costume?” (The answer, for those interested, is here.)

*Oh hey, Luke and Leia are twins, just like Hank and Dean! And I have a feeling that Hank and Dean may not have yet met their “real father” yet either.

*So, wait. I don’t get it. You can say “Chewbacca” in an episode, but you can’t say “Batman?”

*Little miniature timberwolves. Are they bred that way, or do they naturally come in that size in Underland, perhaps because of the lack of food available? Or are they, shudder, timberwolf puppies?

*I was delighted to see Catclops, Manic 8-Ball and Girl Hitler again. I wish we had seen that Manic 8-Ball got a position in the new government at the end. Don’t tell me he died in confinement! The “tiger bomb” couldn’t kill him!

*The “cat hair in the glass of drinking water” beat took two viewings to land for me. The first time I just went “Huh?” when the Baron drinks the water and gets a weird look on his face. And sometimes the dialogue goes by so fast it takes me two or even three viewings just to catch all the lines.

*Brock’s tender mentoring of Hank makes me think, again, that Brock and Hank have a relationship that perhaps even Dr. Venture doesn’t know about.

REFERENCES I CAUGHT:

Return of the Jedi (obviously), my favorite shot being the one where Girl Hitler adjusts her mask so that her moustache can see, an exact parallel to where Lando does the same thing.

Die Another Day for the shots of the X2 being forced down by super-magnet, with pieces breaking off and flying away.

Empire Strikes Back with the thing Underbheit lives in, and the shot of the toupee being lowered down on a thoroughly unnecessary apparatus to attach itself to his head.

Fantastic Four and Underbheit’s taste in the hooded robes of dictators of fictional Eastern Bloc nations.

Simpsons Comic Book Guy for “Lamest. Villain. Ever.”

Dr. Stranglove for ![]() urbaniak‘s “German Guy” accent on the henchman who can stop tonguing the slit (boy does that sound dirtier than it is).

urbaniak‘s “German Guy” accent on the henchman who can stop tonguing the slit (boy does that sound dirtier than it is).

Sin City for the row of women’s heads mounted to the wall.

Silence of the Lambs for the shot of the fingernails imbedded in the chair arm.

All this, and a sly comment on gay marriage too. Bravo!

Found this.

Devil’s Advocate

One of my favorite underrated scripts, by Jonathan Lemkin and Tony Gilroy (who later went on to write two more of my favorite scripts, The Bourne Identity and The Bourne Supremacy), my favorite Taylor Hackford film and, probably, my favorite Keanu Reeves performance (it’s been a while since I’ve seen Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, but I remember last time it made me cry). Plus it’s got Charlize Theron so young she’s still got baby fat.

It seems, plainly, to be a cross between The Firm and Rosemary’s Baby, and while it doesn’t quite reach the heights of the latter, it pretty easily clears the bar (sorry) of the former. It is flatly ridiculous but also well-observed dramatically and morally complex.

It’s not an unusually long movie, but because it’s structurally a little odd it can sometimes feel that way. There’s a fourteen-minute prologue set in Florida, the second act kicks in at 57 minutes, third at 1:38 or so, the movie winding up at 2:16 or so. Because the plot is complex and multi-leveled, it seems like it has too many climaxes, but by the end you can see how all of those things were part of the whole picture (and there was, apparently, more that got cut).

The strength of the script is that it shows, in mostly credible and behavioral terms, the way souls become corrupted. It shows that in real life, there is no midnight meeting at the crossroads with the devil, there is only a series of tiny decisions to be made, day after day after day, that take you further away from “good” and closer to “bad.” Thing is, it doesn’t even really say “bad:” in Pacino’s big monologue at the climax, he explains that all Satan wants is for humans to be happy. And to be happy, humanity only has to give up its guilt. “Guilt is a sack of bricks,” says Satan. “All you have to do is set it down.” Or, as Charlize puts it at one point after a traumatic day of shopping, “Everything is a goddamned test!”

For Charlize, temptation comes in the form of sophistication. In some of the best scenes in the movie, the other wives at the law firm gently pressure her into being hipper, more jaded, more “cool.” The unease that small-town gal Charlize feels thrust into the world of New York highlife is palpable. Just small little choices like getting a new haircut or going against your instincts on decorating ideas become weighted with unexpected morality.

For Keanu, the tempation comes in the form of advancement. If he just gets this job, if he just wins this case, if he just spends this one night away from his wife, then he’ll have what he wants and can be the person he needs to be. There’s one scene toward the end of Act II where he explains all this to Pacino, who suddenly gets a wistful, faraway look in his eye, probably thinking about his performance of these exact same ideas in (the admittedly superior) Godfather Part II.

Then there’s Pacino, drawing the curtain on his “volcanic” phase. He’s mostly delicious in this movie, only really pulling out the stops for the big speech at the end. The scene where he goes through the roof and into the stratosphere, however, requires him to a) tell Keanu that he’s The Devil, b) “explain” a whole bunch of stuff about God, Free Will and Man’s Place in the Universe, and c) convince him to have sex with Connie Nielsen, right there, on a table, in the room, right now. You can see where Pacino might have figured that soft-pedalling the delivery might not have properly sold the scene.

And I have to say, I’m a red-blooded man like anyone else, but I don’t think I could perform sexually, with Connie Nielsen or anyone else, while Al Pacino was standing next to me ranting about God at the top of his lungs. Or anywhere in the room, honestly, doing anything.

I’m a big fan of Charlize Theron in this movie. She’s quite believable and poignant, although she is also saddled with a scene that requires her to tearfully blurt out “They took my ovaries!”

The special effects, like those of many movies made in 1997, have not aged well. Saddest of all is the sculpture over Pacino’s desk that “comes to life” during the climax. The failure of this effect must be at least, in part, due to what I consider a painfully stupid foulup in the clearances dept at WB. They built a whole scene around this sculpture, which they copied from a church in Washington, DC, then found out that the sculpture was a copyrighted work and the sculptor (and the church) didn’t particularly appreciate having it hang over Satan’s desk and didn’t particularly want to be “compensated” for the infringement. The statue had to be airbrushed over in early scenes and significantly altered in later scenes for the video release. Copyright infringement fans can read about the case here.

Late Spring

A young woman takes care of her widowed father. Everyone thinks that the daughter should get married. But the daughter is happy just taking care of her father. That is, until the father announces that he intends to remarry and the daughter is forced to make a decision.

And that’s it, that’s the plot of Yasujiro Ozu’s Late Spring. Oh, there’s a third-act “surprise,” but plot isn’t really the point of Ozu’s films.

The polar opposite of Kurosawa’s operatic dramas and the popular samurai epics of the time, Ozu’s domestic dramas are minimalist, realist, quiet and reserved. In fact, they are in many ways about being reserved. Observational and behavioral in the extreme, they don’t feel like any other Japanese movies I know of. Instead they remind me of Austen and Chekhov, Raymond Carver and Jim Jarmusch.

Like Jarmusch, Ozu’s dramatic strategy sometimes takes a little getting used to. His films may appear to be “boring” for the first half-hour or so as you watch people in mid-20th-century Japan go about their daily lives, cooking and working and eating and gossiping. You’re waiting for the movie to start. Then, as the first act edges into the second and patterns start to repeat themselves, you begin to realize that you weren’t just watching random behavior, you were watching very specific, emblematic behavior, tiny little actions as simple as folding a napkin or raising a drinking glass that, if you had been paying attention, would have told you all you need to know about the characters you’ve been watching. Ozu’s dramas are, in fact, about the way tiny little actions become habit, habit becomes identity, and identity is threatened by change. And as you start to become aware of the “plot,” these tiny little actions start to take on more and more significance. So suddenly, the way someone walks or talks or eats a piece of cake becomes terribly important, as it may contain a vital clue to the character’s inner life, and by the middle half-hour you’re on tenterhooks trying to figure out if people are really saying what they mean, if they’re hiding some terrible secret, if they’re ever going to give their domineering parents what for, if they’re ever going to be happy. Then, by the third act, the accumulated drama, during which no one ever speaks above a conversational tone, invariably becomes almost unbearably moving. Then, typically, a character must face some sort of universal human truth, like, say, everyone has to grow up, or everyone has to pursue their own happiness, or everyone has to die. “That’s just the way human life is,” a character will often sigh near the end of an Ozu picture. And those ideas aren’t new or revelatory, but in the context of Ozu’s pictures they take on the weight of heartbreaking profundity.

Ozu, in addition to being a hugely skilled dramatist, has an utterly unique shooting style as well. He has, essentially, one setup: the camera at the eye-level of a person sitting cross-legged on the floor. This setup remains essentially unchanged whether it’s an interior, exterior, dialogue scene, action scene (well, “action” having a very tiny definition here — a stack of magazines sliding off a chair constitutes an “action” beat in Late Spring), even establishing shots will be shot from the same angle. He also rarely moves the camera at all. I can’t remember a single tilt, pan or dolly in one of his movies, or even a zoom. There are a total of four tracking shots in Late Spring, all of which are used for “walk and talk” scenes, and all keeping the “Ozu angle” intact, as though we are watching the shots from the POV of a man sitting in a Radio Flyer wagon being pulled by a slowly moving car. In addition, he will sometimes have entire dialogue scenes covered in POV shots, with characters delivering their lines directly to camera. It creates an almost unnerving intensity; as actors zero in on you, you want to look away from their gaze in embarrassment. Jonathan Demme used the same technique for an important scene in Silence of the Lambs.

Ozu also used the same actors throughout his entire career. The two leads here, Chisu Ryu and Setsuko Hara are in most of the Ozu pictures I’ve seen, and they never fail to astound. They use an acting vocabulary so different from what I’m used to as an American that I can’t even think of American equivalents to compare them to. Ryu’s permanent little twisted smile and Hara’s ever-heartbreaking hope and despair get under your skin in ways that even great stars like Toshiro Mifune and Tatsuya Nakadai do not. Those guys are movie stars, but Ryu and Hara seem like real people.

My love affair with Ozu began with Tokyo Story, which is him at his heaviest for him. For lighter fare, there is the comedy Good Morning. But my personal favorite is Floating Weeds, which is about a traveling actor who swing by a seaside town for the first time in fifteen years and finds that he long ago fathered a child by a woman he had slept with for a night.

One more thing I should say is that the Criterion Collection has changed my life. I have something in my brain that does not allow me to pay proper attention to bad prints of old movies with corrupted soundtracks. Classics like Dracula and His Girl Friday and It Happened One Night went unwatched by me because I couldn’t watch the terrible murky prints they showed on television. But give me a restored print and a fine, crackling soundtrack and I can watch just about anything, I don’t know why but it really makes a difference to me. So I owe my interest in Ozu, Kurosawa, Bergman, Renoir and countless other great directors to the work done by Criterion.

Oh, and the projector is fixed, obviously. Hurray!