“She Loves You:” a closer look

Above: the young McCartney, pale and drawn, haunted by his recent encounter, and the ensuing recording. Is the awkward pose a kind of code? And why are the other Beatles obviously distancing themselves from McCartney? Are they worried about possible sniper fire?

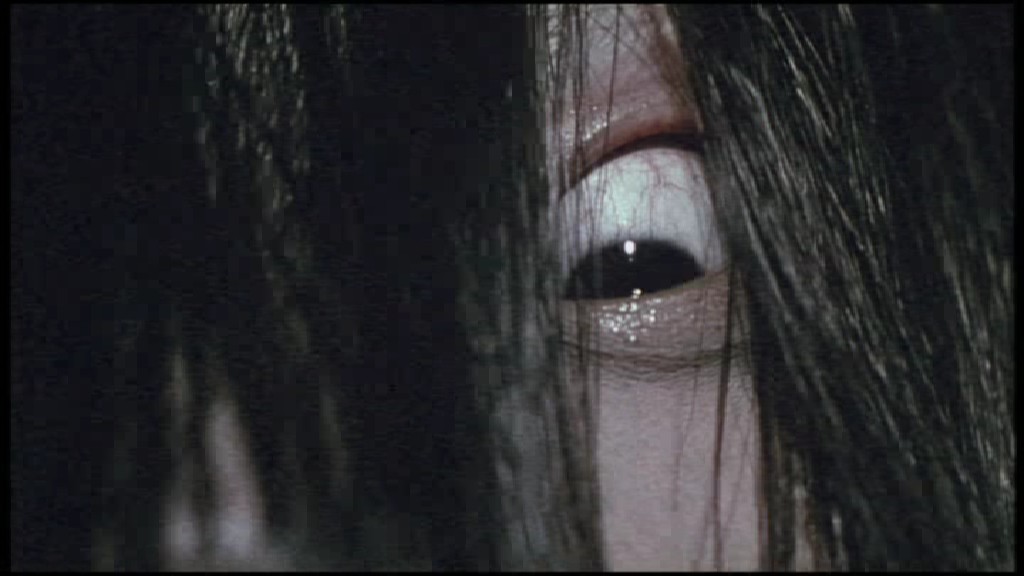

Below: the young woman in question.

______________________________________________________________

Your ex-girlfriend has a message for you. The message is, “She loves you.”

And you know that can’t be bad.

Can’t it?

Let us consider.

It is 1963. You are, presumably, a teenage boy, although the song does not specify age or sex. The point is, you have an ex-girlfriend and she says she loves you.

The question becomes: Who is your ex-girlfriend?

Your ex-girlfriend is, apparently, a person of considerable power and influence. How do we know this? We know this because Paul McCartney is her messenger boy.

McCartney, one of the most celebrated young men in the United Kingdom at this point, has recently been in contact with your ex-girlfriend and she has impressed upon him the overwhelming, urgent nature of her message, which is that she loves you. Not only is McCartney impressed, but he is sufficiently terrified of the repercussions of his failure to deliver this message that he has enlisted the aid of his band The Beatles, overwhelmingly the most popular and influential musical act in the UK, to assist him with this message delivery. McCartney, you see, apparently does not know you personally, nor does he know where to find you. All he knows is that your ex-girlfriend has a message for you and it is his urgent need to deliver this message.

And so McCartney has used every ounce of his compositional talent to craft a bombastic, hysterical football-chant of a song, immediate in its impact and devastating in its catchiness, and has enlisted The Beatles to play it, and on top of that has enlisted the aid of Parlophone records to distribute the recording to every record store in the nation, and Swan records in the United States (and, when their distribution capabilities prove inadequate, Capitol). Every radio station in the English-speaking world will be pressed into service to play it, and The Beatles will even sing a version in German on the off-chance that the message might reach you in Deutschland as well. On top of that, The Beatles, leaving no stone unturned, will eventually visit every civilized nation in the world (and Indonesia), playing this song in concerts before millions of listeners, and will continue to do so for three years, in a marathon attempt to deliver this message to you.

That’s some ex-girlfriend.

Who is she? How did she come to wield such power and influence? Why didn’t McCartney simply say to her “I’m sorry luv, I’m a rather busy pop star and this, frankly, seems to be a private matter?” What methods did she use to impress upon him the overwhelming importance of her love, so that he would spend the next three years of his life delivering the message, through recordings and live performance, to every possible recipient in the hope of reaching you? Your ex-girlfriend, it seems, has an iron grip on the attention of Mr. McCartney.

I think we have to allow the possibility that your ex-girlfriend is unstable and possibly dangerous.

What suggests this? Let’s examine the primary evidence, the message itself.

“You think you’ve lost your love, well I saw her yesterday, it’s you she’s thinking of, and she told me what to say.”

Seems simple enough. Let’s move on.

“She says you hurt her so, she almost lost her mind.”

Okay, let’s stop right there.

Your ex-girlfriend has instructed Mr. McCartney to write in his message to you that she has “almost lost her mind.” What kind of declaration of love is that? “Please come back to me, I’M NOT CRAZY.” This passage speaks volumes.

Now let’s go back to that first line. “You think you’ve lost your love.” Why were you trying to lose your love? What makes you think you’ve succeeded in losing your love? How intense were your efforts, and how diligent has she been in following you? And consider the subtext of McCartney’s desperation: “You think you’ve lost your love, well I saw her yesterday.” What he’s telling you is “You think you’ve lost your love, well, she she was able to get to me, Paul McCartney, the biggest celebrity in the UK, a man of considerable power and influence. What chance do you think you stand of avoiding her? Give it up, for the love of God, talk to her, PLEASE, TALK TO HER.”

And “I saw her yesterday.” Apparently she can get to him any time she wants. Note how in every performance of this song, and McCartney must’ve racked up thousands by now, he still sings “Well I saw her yesterday.” She is, for years, in near constant contact with one of the most heavily guarded personalities of his time. This ex-girlfriend, obviously, has her ways of getting to people, and does not give up easily.

(“Yesterday.” There’s that word, a word that would haunt McCartney for the rest of his life. He saw your ex-girlfriend yesterday; is it only coincidence that yesterday is the same day that so shattered him, that saw him reduced to “not half the man [he] used to be?” There’s “a shadow hanging over me” — a troubling image we will examine the implications of later.)

“But now she says she knows your not the hurting kind.” This line could be read a number of ways. Either your ex-girlfriend is confident in her abilities to overpower you physically (Why not? She’s got Paul McCartney wrapped around her little finger) or else she’s whistling in the dark. You have disappeared, fled this dangerous, unstable young woman, in fear for your life, and in her desperation she has crafted a fiction about the nature of your personality. “Come back, I know you didn’t mean to hurt me, I understand completely and I love you, and I won’t let Paul McCartney out of my clutches until you respond in kind, in order to prove my point.” What could this possibly be except the actions of a crazy person?

(In German! They recorded a version in German! Why? Has your ex-girlfriend expressed a concern that you perhaps have amnesia, and are living in Germany? Does she think, perhaps, that some German-speaking friends or relatives might relay the message to you? What evidence does she have of this? Does she think that, in your desperate avoidance, you have fled the country, changed your name and taken up speaking a foreign language? What the hell did this young woman do to you?)

“Although it’s up to you, I think it’s only fair.” Yes, that’s right, it’s totally up to you. Please don’t let me, Paul McCartney, biggest pop star in the UK, influence your decision in any way, it’s absolutely your decision to make. HOWEVER: “Pride can hurt you too.” Ah, there’s the rub. It’s utterly your decision to make, but YOU WILL FEEL THE PAIN OF THAT DECISION.”

“Apologize to her.” Oh, now wait, what the hell? I thought the message is that she loves you, now she’s demanding an apology? Not herself, of course, no, that’s not her style. No, it’s McCartney, McCartney is pleading with you, please, for the love of God, apologize to her, or you will find yourself in a world of pain. This is no tender declaration of love, this is a plain-spoken threat.

“And with a love like that, you know you should be glad.” Yes, you should be. But McCartney, at this point, is fooling no one. Look at the way certain phrases are repeated, chantlike, over and over — “She loves you, yeah yeah yeah,” “and you know that can’t be bad,” “and you know you should be glad.” This is what Shakespeare referred to as “protesting too much.”

An image forms in my mind. The Beatles return from a world tour, exhausted and terrified from their international mission of message delivery. A pale, drawn, shaken McCartney returns home to London, thinking he’s fulfilled his duty, but is greeted at his door by your ex-girlfriend.

The rain pours down, wetting the young composer’s hair as he stands, crestfallen at the sight of the trembling, enraged young woman. “Did you deliver the message?” She asks. “What was the reply?”

McCartney has no answer. Distractedly, he fumbles with a cigarette. He can’t get a match to strike, not in this sodden English weather. “I didn’t hear back,” he stammers, “I did my best. Please, you have to understand –“

“You didn’t even locate the recipient, did you?” she cuts him off. McCartney goes pale. The cigarette, soaked and lifeless, trembles in his lips. He knows that he will have to go back to the other Beatles and insist that they tour the world once again, enduring constant threat to their lives, in the service of this young woman. It’s going to be another long year.

(Did McCartney, perhaps, actually die in 1966, as was widely rumored? Was it at the hands of your ex-girlfriend?)

More important, perhaps: who are you? What did you do to this young woman, who must be a middle-aged woman by now, if she’s still alive? Are you still alive, or did you pay for your relationship with this young woman with your life? When will it be safe for you to come out of hiding? Are you waiting for another message from McCartney, a song whose chorus goes “It’s all right, she’s dead, you’re in the clear?” What will it take to heal this wound? Can your ex-girlfriend ever be satisfied?

Let’s face it, in the end there is only one possibility: your ex-girlfriend is a supernatural being of terrible power. Your ex-girlfriend may be, in fact, not your ex-girlfriend at all. The song does not, after all, identify her as an ex-girlfriend, merely that she is female, that you “hurt her so,” and that she loves you. She could be your daughter, your sister or even your mother. You may not even be aware of her existence, but she loves you and her love is powerful, constant and unstoppable. She could, in fact, be a ghost and, like Sadako in Hideo Nakata’s Ringu films, she will never rest until her message has been disseminated to every living person on the planet. Which begs the question: what did you do to her? You “hurt her so.” As per Sadako, did you push her down a well because of her awesome powers of destruction?

Whoever she is and whatever her powers, her mark on McCartney was permanent and irreversible. In three short years, she turned him and the other Beatles from cheeky, entertaining moptops to sallow bickering, paranoid drug addicts. What else explains the Beatles’ withdrawl from public life, their investigations into psychedelia and escape into hallucinations, John Lennon’s relationship with the Sadako-like Yoko Ono, George Harrison’s obsession with spiritual life?

What will free the world from the curse of her “love?”

8 1/2 off!

As part of my “movies about crazy directors making movies” research, I just watched Fellini’s landmark classic 8 1/2. I have nothing pertinent to add to the avalanche of praise that this dense, multi-layered, hallucinatory, infinitely graceful masterpiece has garnered, except to note that it seems to have inspired a number of imitators over the years.

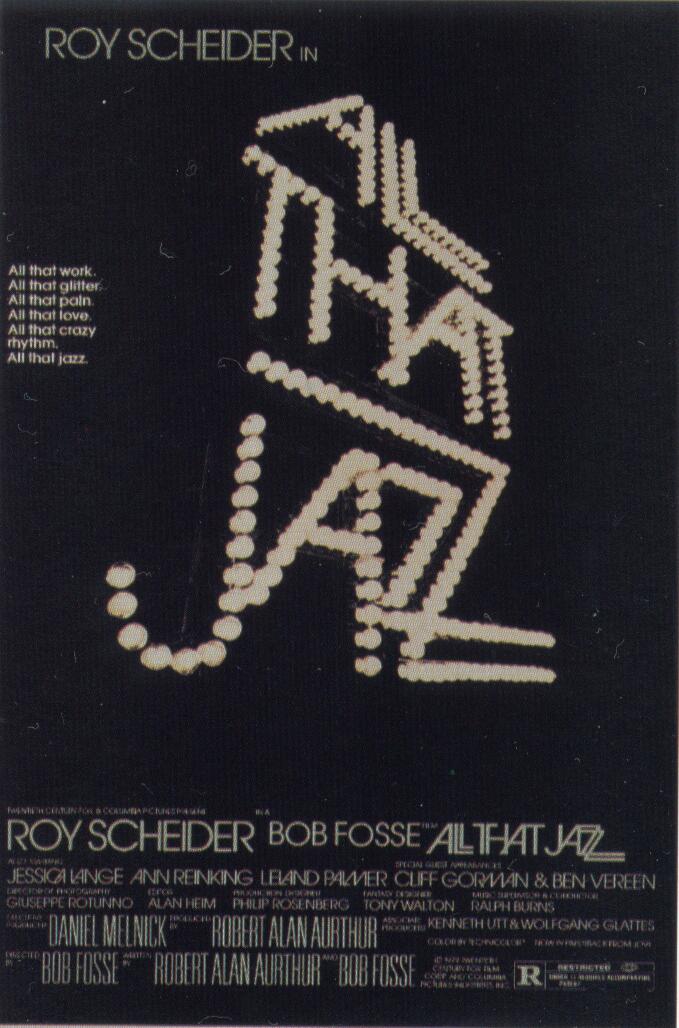

Because I was born into a provincial, parochial Chicago suburb with limited access to classics of European cinema of the 1960s, I probably saw both All That Jazz and Stardust Memories a dozen times each before I ever saw 8 1/2 but both of them strike me as not just “inspired by” the original, but practically direct remakes, at least as much as A Fistful of Dollars is a remake of Yojimbo and A Bug’s Life is a remake of Seven Samurai. (And The Lion King is a remake of Kimba. Or Hamlet, I forget which.)

Both Fosse and Allen lift Fellini’s structure, have their protagonists drift back and forth in time and from fantasy to reality, from the art their working on to the mental processes that create that art. Allen also lifts the black-and-white photography, the “extras as gargoyles” tone, and quotes pretty directly from the dream sequences as well. Fosse does all those things too, but filters it more through his own sensibility.

It’s a tribute to the quality of Fellini’s work that both of his imitators were inspired enough to turn in movies that are, let’s face it, both pretty freakin’ amazing in their own rights.

Who else is there? Are there other movies drifting around out there that we could say are remakes of 8 1/2? Tom DiCillo’s Living in Oblivion comes close, similarly weaving fantasy and reality, dreams and reality, “filmed reality” and reality (it also has more of a nuts-and-bolts attitude to production life — more problems with shooting, less conceptual agony). It has a much more programmatic structure and is more anecdotal in its approach, but serves as a kind of pocket-sized 8 1/2 — call it 4 1/4.

UPDATE: And now that I think of it, Adaptation, in its own way, is a valid entry in the 8 1/2 genre.

Sven Nykvist update

The New York Times reported the other day that Sven Nykvist’s “last film” was the thudding, club-footed rom-com Curtain Call, causing me no end of distress.

I am pleased to report that, while technically true, Curtain Call was not the last feature Mr. Nykvist shot. That honor belongs to Woody Allen’s thorny, scabrous, underrated, impeccably staged, luminously shot Celebrity. Celebrity was shot, cut and released into theaters while Curtain Call was still failing to find a distributor.

I can’t tell you how much better this makes me feel.

Munich

Narratively speaking, Munich is, literally, the oldest story in the book. A handsome young man is called upon to protect his homeland from a monster. He ventures out into the world to slay the monster, thus saving his homeland, but once he returns home he find that the experience he’s gathered in the world leaves him incapable of remaining there.

Thematically, complex questions of nationalism, tribalism, religion and ideology ping-pong and ricochet all over the place. But they all keep circling back to the prime Spielbergian themes of “Family” and “Home.”

And then there’s the question of “Home.” The Jews want a home, but so do the Palestinians. The espionage family has a wonderful, warm home in the French countryside. Everywhere Eric turns, people are falling in love, having children, setting up housekeeping, making plans. The terrorists targeted for assassination are shown bickering with their wives and doting on their children, going on dates and having parties. There isn’t an inhuman one in the bunch and they all seem to have nice homes and good families.

In terms of genre, something of a head-scratcher. It’s structured like an espionage thriller, like Three Days of the Condor, and certainly is as suspensful and gripping as that movie, but tonally it feels closer a historical drama like Schindler’s List.

Spielberg works very hard to keep things real and cliche-free and mostly succeeds (some cliches do slip through, such as the cold-blooded assassin cooly walking up a darkened staircase while slipping on his black leather gloves, or the espionage guys talking about assassinations and terror plots while slicing vegetables or tinkering with toys). The assassination sequences don’t look or feel like anything ever shown before. The assassins are human and prone to mistakes and improvisation. Nothing feels planned or flawless (unlikethe assassinations in Three Days of the Condor). For every cute Spielbergism that slips through, there are a dozen scenes of stunning originality, like the assassination of the woman in Holland. Not a pleasant film by any means, I had to take a break in the middle of watching it — not because of its unpleasantness, but to catch my breath, which I had been holding rather too much without realizing it.

Venture Bros: I Know Why the Caged Bird Kills

In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Shakespeare wrote “the course of true love never did run smooth,” and while this episode of The Venture Bros shares much with that play, including star-crossed lovers and magical spirits, I doubt Shakespeare could have ever come up with a path to true love involving Catherine the Great, Henry Kissinger, a haunted car and a refugee from American Gladiators.

As with any love story, “I Know Why the Caged Bird Kills” has two protagonists, The Monarch and Dr. Venture. Both protagonists have love problems (to say the least), but for the moment, neither protagonist can pay attention to them. (Typically for this show, the Monarch’s plot is active, with him trying to solve his administrative problems, while Dr. Venture’s plot is passive, with him merely trying to get rid of his immediate problem so that he can go back to his life of steadily increasing failure.)

The Monarch’s attention is taken up by an immediate problem, that his plans to attack Dr. Venture are failing. His henchmen (at least 21 and 24) believe that the problem is one of armament (which is absurd, as the attack shown at the top of the episode is the most well-armed and effective in The Monarch’s history). Meanwhile, Dr. Venture is being harrassed by a vengeful Oni.

Meanwhile, The Monarch is visited by a mysterious stranger, Dr. Henry Killinger and his magic murder bag. The Monarch, impressed with Killinger’s organizational skills, allows him free access to his staff and secrets. In no time at all, Killinger has an elite staff of Blackguards in cool suits and has completely re-organized the Monarchs’ operation (Literally, in no time at all. Killinger does all this in the time it takes for Drs. Venture and Orpheus to walk from the library to the parking lot).

Henchman 24, suspicious of Killinger’s intentions, refers to him as a “sheep in wolf’s clothing,” and while that sounds like a mere malapropism, it’s actually a key line in the episode. Because we see that, in each plot here, love comes disguised as hate, tenderness disguised as threat. Myra shows her love for Hank and Dean by kidnapping them, 21 shows his love for the Monarch by bringing in Dr. Girlfriend to infiltrate and assault the cocoon (and ends up falling in love with her, but that’s another story). I will also argue that the Monarch’s obsession with and attempts to destroy Dr. Venture also constitute a kind of love, one paralleled by Myra’s obsession with and attempts to destroy Dr. Venture’s family. (It also occurs to me that Henry Kissinger was the inspiration for Dr., ahem, Strangelove.)

And then of course there is Dr. Killinger, who turns out to be not a malevolent figure of doom but a magical spirit of love and reconciliation (would that his real-life counterpart turn out similarly), and the Oni turns out to be working for him. Killinger is shown to be a fat, male version of Mary Poppins, which, again, seems completely lunatic on the face of it, but underneath has a deep thematic resonance with the rest of the show.

The protagonist of Mary Poppins, lest we forget, is not Mary Poppins but rather the father. What does the father in Mary Poppins want? The same thing as Dr. Venture — to have someone, anyone besides himself take responsibility for raising his children. A key difference between Dr. Venture and Dr. Benton Quest is that Race Bannon is assigned to be a bodyguard for Dr. Quest’s son Jonny, Dr. Venture has hired Brock to be a bodyguard for himself; the boys’ safety is never anywhere on Dr. Venture’s list of priorities. Brock, the much better parent of the two, seems to take on the boys’ safety himself, but only to the extent that it’s usually too much trouble to clone them again. If the boys die, well, there’s always more where that came from. The father of Mary Poppins at least hires a nanny; Dr. Venture is content to leave that job to an inadequate robot and the “lie machines” that talk to them in their sleep. The father in Mary Poppins, of course, learns his lesson and re-centers his life around his children; Dr. Venture, I fear, will never learn that lesson.

The theme of this episode is the course of true love, but there is a sub-theme of misguided rescue. Hank and Dean, out practicing their driving skills, happen upon a stricken woman, who turns out to be a deranged ex-girlfriend of Dr. Venture. They set about rescuing her, but end up being taken captive by her. Later we will find that she feels that she is “rescuing” them from Dr. Venture. The henchmen misguidedly try to rescue the Monarch, and even take turns rescuing each other at different points of the episode.

Of the episode’s short-circuited love affairs, the most elliptical is the one between Drs. Venture and Orpheus, which seemingly ends with Dr. Venture hysterically accusing Dr. Orpheus of coming on to him, then mysteriously seems to begin again when he, minutes later, casually suggests that they watch pornography together. This rocky, contentious relationship is presented as a contrast to the other “true loves” of the episode.

In an episode rife with parallel scenes, Brock and Helper are given a nice pair where, in one scene, Brock attempts to educate Helper on the subject of Led Zeppelin, and in the next, Helper is educating Brock on the poetry of Maya Angelou.

The advice Dr. Orpheus gets from Catherine the Great’s horse is never revealed — but given the circumstances, that might be for the best.

(Strangely enough, although Myra’s story is explained away by Brock, her own version of events makes more sense. In her version, she rescues Dr. Venture’s life during the unveiling of the new Venture Industries car, and later the two of them have sex in that same car, and it is that car that the Oni chooses to haunt in order to bring Dr. Venture to Myra. So perhaps Brock’s story is the inaccurate one after all.)

Contempt

If Harold Pinter wrote a version of The Big Knife, it might come out something like this.

I’d be kidding you if I said that the movie struck me immediately as a masterpiece. Because it’s Godard and for me, Godard always comes off as willfully opaque and even boring on first viewing. It takes some time, in this case 18 hours and a good night’s sleep, for his narrative strategies to reveal themselves.

A french writer (A novelist? A playwright? We’re not sure; he describes himself as a playwright but his wife says he’s a “crime novelist”) living in Rome is hired by a boorish (that is, American) producer to “fix” a new film by director Fritz Lang (played by, well, director Fritz Lang). The film in question is an adaptation of “The Odyssey.” The director wants to put myth on screen, gods and goddesses and mermaids, heroism and simplicity. The producer wants to make Ulysses a “modern man,” ie neurotic and perverse, so that the audience will have a way into the story. The writer is caught between these two impulses.

None of this is immediately apparent.

The writer is married to Birgitte Bardot, the ne plus ultra of “desirable women” in 1963. He has, in other words, everything a man could want. He is offered the job by the producer and goes to the studio to watch what there is of the movie the director has made.

(The film, as shown, appears to be even more opaque and than the one we’re watching. Only a few of the shots are of actors doing things, the rest are shots of Greek statues posed in fields. When actors appear, they have no dialogue, only a few poses and motions. If the director was trying to resurrect the gods, he’s crashed on the shores of film’s limitations — a static shot of a painted statue does not evokes godhood, it evokes tackiness and pretension.)

After the screening, the writer, completely baffled, is invited by the producer to come back to his villa to talk. The producer offers the writer’s wife a ride in his Alfa Romeo and the writer encourages her to go. This action, for reasons that remain mysterious to the end of the movie, ends his marriage, although it will take him the rest of the movie to figure that out.

The producer asks the writer and his wife to come to the set in Capris that weekend and they part. The writer and his wife go home to their flat somewhere in Rome. We’re all set for an involving drama about the making of a motion picture, but Godard, as Godard will, dashes our expectations and instead gives us a half-hour scene in the couple’s apartment where the writer asks his wife, over and over, in a dozen different ways, if he should go ahead and take this job, and what happened that afternoon that has made her start acting so strange. Did the producer do something to her in the car? Did the writer say something to offend her? What the hell is going on? Birgitte Bardot is pissed, and one tends to want to know what Birgitte Bardot is pissed about. The couple putter around the flat, take baths and set the table, start twenty different halting, incomplete conversations, take off and put on clothes, hats and wigs, fight and make up and fight again and make up again. This scene takes up the entire second act of the picture and, like many things in a Godard picture, the purpose of it remains hidden for a while.

The writer and his wife, in any case, go to Capris. The writer takes walks through the wilderness with the director where they discuss what writers and directors have always discussed: What does the protagonist want? That is, Why does Ulysses go off to the war to begin with, and why does it take him ten years to get home? The director believes that that’s just the story, it is what it is, but the writer believes (or is being paid to believe) that Ulysses went to the war to get away from his wife and is taking his sweet time getting home because he’s not sure if he ever wants to see her again.

Aha, so that’s what the 30-minute Pinteresque flat scene was about. The writer whines and grumbles about how he wants the job and worries about whether his wife still loves him, when secretly he wants to both reject the job and get rid of his wife altogether. The man who has everything is intent on throwing it all away.

And so in the end (spoiler alert) the protagonist of this movie gets exactly what he wants, although not in the way he expected. Instead, the gods that the director wanted to put in his movie enter, as gods often do, offscreen, in the form of , literally, a deus ex machina. When I was a youngster, a high-school comp teacher warned that the weakest ending imaginable is “And then they were all hit by a truck.” Godard, surely, must have had that rule in mind when he devised the ending for Contempt, a fitting end for a movie about modern perversity.

Renaissance

Go.

See it on the biggest screen you can.

You have never seen anything like it. This I promise.

Required viewing for anyone with an interest in the art of animation.

The story is a sci-fi noir not unlike Blade Runner or Minority Report (but without the Dickian moral complexities); the look recalls Sin City but more styized (ironically, it looks more like a Frank Miller graphic novel come to life than that movie did) and the visuals are absolutely mind-blowingly staggering. Without exaggeration, I would say that there are more fresh ideas and innovations in any given three minutes of this film than there are in most other entire animated features.

Made me believe that there is still something new to say in the art form of film, that we haven’t quite reached the boundaries of this medium.

The Jonny Quest title sequence: an appreciation

What’s happening on this DVD cover?

Someone has stolen the jet! And we need it, because either

it’s a beautiful sunset, or else an atomic bomb has gone off!

Quick, let’s run to see if we can, I don’t know, outrun the atomic

blast! Maybe Skeet Ulrich will be able to help! Bring the

binoculars, Dr. Quest! Lead the way, 10-year-old boy! Let’s

bring the dog, we might need him to eat later!

My interest in The Venture Bros has led me to Jonny Quest. Any fans of VB out there, I urge you to try to watch some of this show. There will be much you recognize, and the show is also a valuable viewing experience on its own terms.

Jonny Quest was one of those shows that I watched the title sequence of every week but never stuck around for the whole show. I could name dozens of others, including Baretta, Mannix, Perry Mason, Ironsides and Barnaby Jones.

But now that I’m actually watching the show, the title sequence has a bizarre, compelling logic all its own. Quite apart from the bizarre, compelling logic of the show.

First of all, there is no title card telling us the name of the show, which has to be a first. Apparently the title of the show must have been announced elsewhere, because each show starts cold with:

Jonny? Dr. Quest? Race? Hadji? Bandit? No!

INDIANS! Indians run through some jungle undergrowth. Why are they running?

CUT TO: Some Guy in torn clothing, also running through the jungle, looking rather upset. The Indians are chasing him! No wonder he’s upset! Who is this man? Is this who the show’s about?

No time for questions! Here comes a LARGE PURPLE PTERODACTYL, diving out of the sky, its mouth agape, a savage screech emanating from the depths of its prehistoric lungs. Is the pterodactyl going to swoop down and get the worried man before the Indians catch him?

No! The pterodactyl is apparently after A PANTHER, who looks up from a patch of jungle as though hearing something, maybe a pterodactyl screeching and diving out of the sky.

MEANWHILE, on the other side of the jungle, aCROCODILE slithers silently into some swampy water.

BUT HERE COMES THE PTERODACTYL again! He can’t seem to make up his mind who he’s going to swoop down upon!

Luckily, THE ARMY is here! And they’ve got machine guns! And they’re shooting them! Are they shooting at the pterodactyl? Is that the best way to deal with the appearance of a prehistoric creature?

But wait! No, they’re not shooting at the pterodactyl at all, they’re shooting at A LARGE, ROBOTIC WALKING EYE! A LAVENDER walking eye, no less! Why? What threat does the walking eye pose to the army men with the machine guns? It must be a pretty big threat, because HERE COMES A TANK for backup! The tank FIRES at the Walking Eye, blowing it to Kingdom Come! The world is safe from the menace of Walking Eyes!

Meanwhile, a MUMMY staggers down a well-decorated hallway. It SMASHES through a wall with all the strength and unstoppable power of a 5,000 year-old dried-out corpse.

It must be a very threatening mummy, as TWO GUYS in colorful hazard suits fire rifles at it!

With no affect! The mummy PICKS UP an EGYPTIAN GUY in a fez!

While RACE BANNON (the first appearance of an actual character from the show) shoots at the mummy with a rifle, causing a CAVE IN that clouds the screen in an explosion of dust.

LATER, or MEANWHILE, or APROPOS OF NOTHING, four guys in bright red Cyclops uniforms glide over the eerie, desolate surface of the moon in special tin-can-shaped hover-pod-craft.

Back on Earth, a VULTURE swoops down out of the sky. So many winged creatures in this show, so much swooping. And here’s poor BANDIT, a small, adorable bulldog, running for his life! Look out Bandit! Too late, the vulture has scooped him up from the ground!

Is the vulture going to eat Bandit? Or is he just rescuing him from the TRIO OF DEADLY POISONOUS ADDERS slithering across the ground? Or maybe from the pair of LEASHED KOMODO DRAGONS skulking through the bush?

Don’t worry Bandit, here comes Race Brannon, swinging off the deck of a moss-covered shipwreck! He’s — he’s — he’s kicking over a guy in a lizard outfit, that’s what he’s doing! That’ll fix those adders and komodo dragons! But he’s too late! Another Lizard Guy fires off a LASER CANNON from the deck of the moss-covered shipwreck!

The laser blast annoys DR. BENTON QUEST, who, as luck would have it, is seated at the controls of AN EVEN BIGGER LASER CANNON, which he fires in defense tout suite! It’s facing the wrong direction, but Dr. Quest is, apparently, prepared to overcome this problem, as his laser blast somehow magically CHANGES DIRECTION and BLASTS the moss-covered shipwreck, killing all the lizard-guys! Hooray!

Later, a jet plane glides through the stratosphere, and THE TITLES BEGIN. Still no main title, but at least we get to know who the characters are.

And look! One of them is a little blond boy named JONNY QUEST, who apparently is the star of this show, even though this is the first (and only) time we will see him in the title sequence. Apparently he was too expensive to book for the earlier shots. He sits looking out his airplane window, looking for all the world like he’s bored and distracted by having to be in a TV show at all.

When his name appears onscreen, a very strange thing happens. Jonny does a take to camera, but it’s not a smile or a thumbs up or a wink; he gives us a sly, condescending nod, as if we’re old friends of his and share a deep personal secret with him. I can’t tell you how much this shot unnerves me. I don’t wantto share a deep, personal secret with a ten-year-old boy I’ve never met before. How did the animators achieve that look? Why did they? Why isn’t Jonny just happy to be on a TV show? Why can’t he smile and wink, why does he have to give us this sleepy, indolent nod and weary, sexy grin? How am I ever going to un-see this shot?

Dr. Quest, Race (or “Race” as they spell it) and Hadji, for their part, do not even deign to look at the camera as their names come up; they’ve got other things on their minds. Dr. Quest, at least, isn’t wearing the perpetually pissed-off scowl that he wears in every other shot in the show; here he almost looks as though he might actually be enjoying himself on this silent, conversationless jet trip. Race is busy piloting the jet of course, he doesn’t have time to participate in title-sequence shenanigans, and Hadji is too interested in the antics of Bandit, who looks out the window and barks. At what, we don’t know. Maybe he’s just trying to break the deadly still mood of this silent jet where no one speaks and no one can even look at each other.

Dr. Quest has a problem with his son, which will be explored in posts to come, but all the dynamics are right there in the final shot: the two adults sit in front, staring dispassionately out at the world crawling slowly below them, and the two ten-year-old boys sit in back, not speaking to each other, smiling wanly as though remember some fond memory of lost love as the jet hurtles through the sky.

Sven Nykvist

Sven Nykvist, sadly, is no longer the world’s greatest living cinematographer.

I am both extremely proud and terribly ashamed to be the author of Curtain Call, Mr. Nykvist’s last film. He was very kind to me, a young, unproven whippersnapper, and everyone else on our crew. He told me a funny story about working with Tarkovsky and expressed, with total good humor, his frustration with working with Woody Allen. My pathetic excuse for a romantic comedy was far below the typical material he worked with and I feel blessed to not only have had him shoot my script, but to actually have lit me for a cameo scene.

I knew that he was a great cinematographer when I was working with him, but like the philistine I am I did not see his work with Bergman until long after we parted ways. Had I seen, for instance, Through a Glass Darkly before I met him I doubt I would have been able to look him in the eye, I would have been too ashamed to work with so great an artist.

Seven Samurai

First of all, there is a new edition of Kurosawa’s masterpiece out now from, of course, Criterion. It’s rather staggering in its quality. If you’ve never seen the movie, you’ll never have a better chance to experience it than now. Even if you own the previous edition, just go out and buy the new one, I’m serious, it’s just rather staggering.

Plenty of words have been spent talking about this movie so I’ll keep this brief.

Kambei (a career-best performance that made me fall deeply in love with Takashi Shimura) seems to have decided that a samurai is something like a warrior monk. When we meet him, he’s actually disguising himself as a monk in order to root out and kill a desperate, kidnapping thief. Later, when a group of penniless farmers ask him to assemble a team to aid their village in battling an army of vicious bandits (also ex-samurai), Kambei accepts the job even though there is no money and no glory involved.

The farmers constantly complain about how poor they are, but in a land where no one has any money, they are the ones under attack because they have the only thing worth anything: food and land. The samurai, once a wealthy, influential class, are now in the same boat as everyone else, and Kambei has apparently decided that when no one has any money, what is valuable is one’s actions, one’s code, one’s behavior. In his case (he is in the minority among samurai) he seems to think that being a samurai involves helping desperate people in need for free. His altruism inspires four other samurai of various background and experience to join the team. One is an old friend, one is a genial goof, one is a remote, opaque killing machine, all represent, again, greatly differing ideas of what a samurai “acts like.”

Then there is Katsushiro, a teenage samurai who attaches himself to Kambei out of fawning idealism, and Kikuchiyo (Toshiro Mifune, in a brave, off-the-rails Depp-like performance) as a drunken fraud who’s only pretending to be a samurai.

Kikuchiyo, we learn, was once a farmer himself, and has promoted himself to samurai out of shame for his background and the supposed glamour and class elevation of samurai. But once we get to the village, we learn that the samurai are despised and reviled by the farmers, who don’t trust the very people they’ve hired (for nothing) to guard their village with their lives. In fact, we learn that the farmers have actually killed other samurai who have passed through, out of fear and supposition of how a samurai acts.

And so Kambei and his team of samurai, wanting nothing but to be helpful and good, encounter nothing but dishonesty, greed, trickery, fear, suspicion, small-mindedness, theft, short-sightedness and stupidity. Given all that, Kambei has every reason to a) say “The hell with this” and leave the village, or b) join the bandits and destroy the place. But he does not; with each affront, he merely gives a discouraged look, rubs his shaven head and gets on with his work. It’s all he knows how to do, and something inside of him tells him that it will all somehow be worth it.

In the end, whether it has, indeed, been worth it, is the movie’s lingering question.

And so the samurai train the farmers to become samurai too, further blurring the distinction between samurai and non-samurai. And soon, everyone in the movie starts questioning their roles, wondering what it means to be a farmer, a father, a man, a woman, a wife, a patriarch. In one key scene, the teenager Katsushiro is romping in a sylvan glen with his farmer girlfriend, and she literally throws herself in front of him in sexual frustration, demanding “Damn you, why can’t you act like a samurai?!” and poor Katsushiro can only stand and stare in trembling fear. And who can blame him? He hasn’t got the first clue how to “act like a samurai.”

(Later on, when Kikuchiyo sits mourning the death of one of the farmers, Kambei chides him by saying “What are you doing? This isn’t like you.” Kikuchiyo has let Kambei down by dropping his facade, by not pretending to be a loud, cockeyed brazen fool for once. I’m reminded by Vonnegut’s quote, “We are what we pretend to be, so we have to be very careful about what we pretend to be.” I’m also reminded that having courage and pretending to have courage are actually the exact same thing.)

One of the samurai paints a satirical banner intended to make fun of Kikuchiyo, but in the end it is Kikuchiyo, the one who admittedly isn’t even a samurai at all, who pulls the team together and turns them into a fighting force. When one of the samurai is killed in a raid, he grabs the banner , climbs to the top of a house and plants it. It whips in the wind and suddenly everyone sees “Yes, this is what we are, the hell with all the suspicion and misunderstanding, we are samurai, no matter what the hell our doubts are, and we’ve got a job to do, so we’d better get our minds together and do it.”

When the bandits finally show up on their murderous rampage, Kambei does not seem fearful or tense; rather, his sense of relief is palpable: finally, a battle, something he actually knows how to do.

When Katsushiro finally gives in to the girl’s demands and “acts like a samurai” on eve of the final battle, the results are devastating. The girl is thrashed by her father for being a slut and Katsushiro is mortified by his actions, even though he was motivated by tender love instead of brutal lust. When the battle against the bandits is won and the farmers go back to their simple, happy lives, Katsushiro is caught in a double bind: his girl no longer needs him, his destiny as a samurai will lead him elsewhere and he still has no idea what he is supposed to do.