Soylent Green

WHAT DOES BIG BROTHER WANT? Big Brother wants only to feed the world. Who doesn’t want to feed the world? Go Big Brother!

WHAT DOES THE REBEL WANT? The rebel wants only to solve the murder of Joseph Cotten. Who wouldn’t want to solve the murder of Joseph Cotten? Go rebel!

WHAT DOES THE REBEL GET? The rebel does, indeed solve the murder of Joseph Cotten. And a whole lot more.

IS THERE AN UPPER CLASS, AND DO THEY HAVE ANY FUN? There is and they do. They have clean apartments, soap, hot water, towels, alcohol, you name it. Fun ahoy!

DOES SOCIETY CHANGE AS A RESULT OF THE REBEL’S ACTIONS? Well, he sticks a defiant, bloody hand in the air and says “Somehow we’ve got to stop them!” before he’s carted off to Waste Disposal, so I guess that counts for something.

NOTES: By far the best-constructed, most entertaining of the Charlton Heston sci-fi world-gone-wrong trilogy. Like Blade Runner and Minority Report, it tells us its skewed worldview through the guise of a detective story. It’s not a very complicated detective story, but the sheer level of detail brought to the worldview is convincing and pervasive. It’s not so much the physical details — the design world, in 2022, has ground to a dead halt in 1973 — but the characters’ attitudes, the sheer level of acceptance everyone has of “well, this is how the world is.” This is introduced most vividly in the opening assassination scene — the assassin isn’t a bad guy and neither is the victim; one’s been hired to kill the other and they both just kind of sigh and get on with it. That stunning scene sets the tone for the whole movie: people just kind of accept living in cars, or having to pedal a bicycle for their own electricity, or having dozens of homeless people living in their stairwell. Women just kind of accept being treated as chattel and having police detectives ransack their house, stealing everything that isn’t nailed down. The poor just kind of accept that there will be shortages, and when they riot, they just kind of accept that the police will respond with bulldozers. It’s not pleasant, but what are you gonna do? Everyone, rich and poor alike, just kind of accepts that everything is rotten and there isn’t anything you can do about it. It’s the apathy in the movie that gets to you, not the production design, and it shows how a single idea and a mastery of tone can go a long way toward carrying a movie. Because, let’s face it, the detective story in this movie is practically nonexistent. The protagonist barely does any detective work at all; he punches people and asks them what’s going on while his elderly pal reads books and then goes asks somebody what’s going on and then they tell him. There is no puzzle or layers of intrigue, rather it’s riddled with cliches (the detective gets involved with the doomed dame, pursues the hot case too far and catches heat from his superiors, blah de blah de blah). The triumph is all tone and the looks on people’s faces. When Chuck Connors shoots a priest in the head in a confessional, neither party seems surprised or even particularly uspet by the encounter.

It’s a shock to hear phrases like “Greenhouse effect” tossed around in a movie made in 1973, especially when the result of that effect is the world described here. The whole thing seems creepily plausible, a world where an assassin has to go to a special contact to acquire a meathook but has no trouble getting a handgun.

Edward G. Robinson’s performance is as good as everyone remembers it and in a way, Soylent Green is a love story between Heston and Robinson, just as Double Indemnity is a love story between Fred MacMurray and Robinson. I guess he was just that lovable.

Special bonus points for this movie for having Dick Van Patten realize his potential as an actor by appearing as a suicide assistant.

Brice Marden

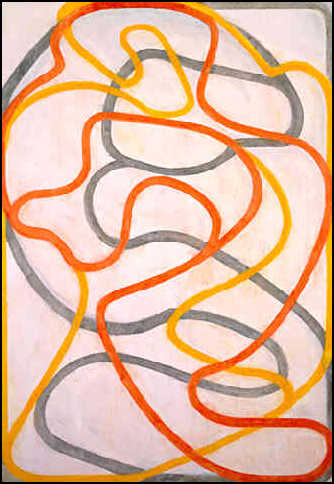

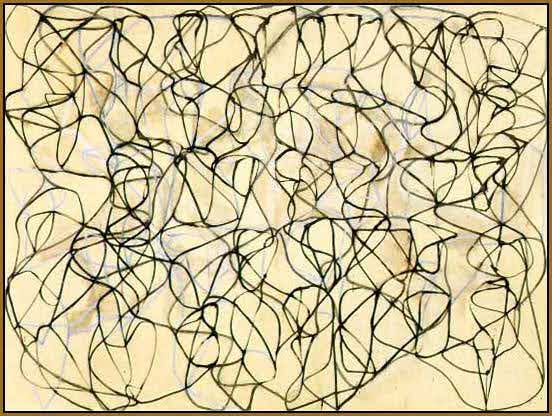

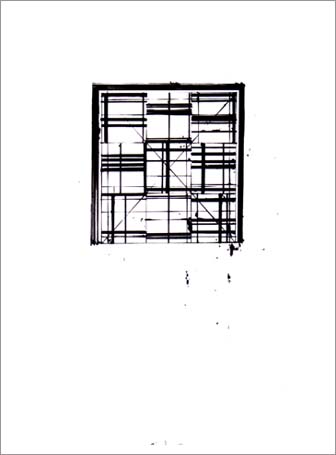

Brice Marden, America’s greatest living painter, has what I believe is his first full retrospective of his work showing at MoMA right now through mid-January.

If you care anything about abstract art or American painting, or if you have a soul, I encourage you to see this show.

Yes, that’s right, when I’m not dissecting TV shows, writing movies about talking bugs or watching movies about futuristic utopias, I can often be found strolling about the world’s institutions of modern art, searching for dramatic collusions of lines and colors.

I was not always like this. I used to think abstraction was a fraud. I didn’t “get” it, I thought the artists were either delusional, working under an exaggerated or even fabricated sense of their own importance, or else laughing at us as we gazed in confusion at their messageless works.

Brice Marden changed all that.

I still remember quite clearly when it happened. About 10 years ago I was in Cambridge with my bride-to-be and I stopped in at the local art joint to see a couple of Sargents they had on display. I never got as far as the Sargents because there was a show of Brice Marden drawings on the first floor. They were opaque and confounding, yet lyrical and intriguing at the same time. They were, I found out, drawn with anything but a pen — Marden will use twigs or shells, dipped in ink and held at a distance, to keep his line naive and undisciplined — and utterly bewitching. They looked like trees or vines or hedges or something, but they were both that and not that; they were both representative of things and also just marks on paper. And suddenly I “got” abstraction. In fact, I suddenly understood what the word “abstraction” means.

And the floodgates were opened. Suddenly I “got” Pollock and DeKooning, Sigmar Polke and Gerhard Richter, Barnett Newman and Cy Twombly (O! Cy Twombly — for added value, there are also a half-dozen crucil, essential Cy Twomblys hanging in the Big Gallery space at MoMA). And I went from being a guy who thought abstraction was a fraud to being a guy who now can barely tolerate representation — I keep thinking a representational artist is trying to sell me something. And now I’m the kind of guy who drags reluctant friends and family to places like the Dia Center in Beacon NY to see Richard Serra’s Torqued Ellipses (I’m still cursing myself for not getting to Houston for the Twombly show a few years ago). Now I’m the kind of guy who stops to look at a crack in the sidewalk or a badly-painted wall or a carelessly-whitewashed window. For me, a painted surface is now filled with light, a line brings in drama and a whole bunch of lines, artfully arranged, can produce an almost unbearable tension.

You may hate the Marden show. When I was there today there were plenty who did. Galleries were dotted with confused middle-aged women and disgusted middle-aged men, wavering between not being sure if they were being conned and utterly sure they were being conned. The men were particularly angry about it, sniggering to each other, voicing their moral superiority, muttering threats to the artist and, in one case, even wishing him a violent death. I’m not sure what provokes a reaction like that, I don’t know what one is expecting when one comes to the Museum of Modern Art. It seems to me that someone who sees a show as positive, life-affirming and glorious as this and reacts with a wish of violence upon the artist probably shouldn’t bother walking into an art museum in the first place.

UPDATE: Thanks everyone for writing in. For the folks who hate this stuff, let me reiterate, I used to hate it too. Now I don’t and this guy is the reason. I’m not an art historian, I’m not a theoretician and I’m sure as shootin’ ain’t no elitist. He opened up a whole new artistic world for me and I’ll never forget it.

And for those who like this stuff, here’s a few more. Thanks again!

Gattaca

WHAT DOES BIG BROTHER WANT? Well, there is no “Big Brother” per se, but society wants perfection, and it knows how to get it.

WHAT DOES THE REBEL WANT? Same as anybody, to go into space. I think “space” here represents “heaven.” The protagonist has been damned by unfortunate birth to hell; he’s going to fool the gatekeepers of heaven into letting him slip by.

WHAT DOES THE REBEL GET? With the aid of an unfortunate perfect-guy (who condemns himself to flames of perdition just as the protagonist is lifted into heaven), plus the love of a beautiful woman (nothing, NOTHING is accomplished in a Futuristic Dystopia without the love of a beautiful woman), plus the last-minute good will of a company doctor, he gets his wish.

DOES SOCIETY CHANGE AS A RESULT OF THE REBEL’S ACTIONS? Revolution isn’t really the protagonist’s goal here, and not even escape really. He wants to belong; he wants to know he’s good enough to go to heaven. The screenwriter chose the term “Valid” for a reason.

NOTES: The theme of the movie, it seems to me, is Will. Does the protagonist have sufficient will to achieve his goal? Does he have what it takes to overcome his genetic predisposition, switch identities with another guy, keep up the ruse for years, endure loneliness, constant, obsessive vigilance in cleanliness, break his own legs, live with Jude Law?

The fimmakers face a problem, of course: genetic science and astrophysics are dull, cerebral subjects. How to juice up the narrative and compel audience interest? MURDER! MURDER MOST FOUL, that’s how. And so, on his way to the stars, our protagonist gets caught up in a murder investigation that seems important only to the police. Indeed, no one seems interested in or excited by anything in this sterile, unpopulated future; to be excited, I suppose, would be to be less than perfect, which everyone is, or pretends to be.

Our protagonist is totally obsessed, to a ridiculous degree, with getting to the stars, and yet, with days to go before launch and a murder investigation breathing down his neck, he decides to take a chance in romancing Uma Thurman. This in spite of the risk of exposure, the unhygenic quality of sexual contact, the possibility of getting “girl germs” and the fact that Uma doesn’t seem to have much of a pulse. Perhaps he feels that if he can’t reach the stars in heaven he can at least have one in his bed on Earth.

Then, cleared from his murder investigation, given a clean bill of health from his corporation, and ready for launch, the protagonist must still face down his brother/detective for one last suicidal swim. Boys, as the saying goes, will be boys.

One of my posters pointed out in the previous entry that the society of Gattaca is filled with genetic flaws despite science’s best efforts, but I’m not sure that’s what the movie is trying to say. There is the usual assortment of Valids and In-Valids in society it seems, and they all seem to get along okay, although the Valids seem to lord it over the mutts a little bit. There is the six-fingered pianist, but it’s unclear from the script whether the pianist is a genetic freak or a planned accident — that is, is he another kind of outsider, like the protagonist, an In-Valid who has overcome his genetic deformity to find a place in Valid society, or did his parents actually give him six fingers on purpose so that he could become a great pianist? “That piece can only be played with six fingers,” says Uma, indicating that the piece in question was composed specifically for someone genetically modified.

Futuristic Dystopias, Part II

It is time to separate the wheat from the chaff.

Here is a list of movies:

Metropolis

Fahrenheit 451

Zardoz

A Clockwork Orange

Soylent Green

THX 1138

Sleeper

Logan’s Run

Rollerball

Blade Runner

1984

Brazil

Gattaca

The Matrix

Minority Report

Code 46

The Island

V For Vendetta

A Scanner Darkly

If you, like me, are a Hollywood screenwriter, you will see not one but two lists here. There is a short list of movies that were very successful and a longer list of movies that were not successful. We’re not talking about artistic success here, just boxoffice. A few of them were smash hits, some were middling disappointments, some were high-profile disasters and others escaped the notice of almost everyone.

My job is to figure out why. Why did audiences connect with some of these movies and not others?

They all share the Futuristic Dystopia element, which puts them in the realm of sci-fi, but some of them mix in other genre elements as well. Blade Runner and Minority Report are detective stories, The Island and The Matrix feature action-film elements.

Each has a single protagonist in opposition to his or her society. That society is either (a) forthrightly awful or (b) awful with a sweet candy-coating that must be peeled away before the awfulness can be tasted.

The key, it seems to me, is in the journey of the protagonist. Specifically, the protagonist must be active, and must represent something unique and important.

Let’s compare The Matrix and V For Vendetta. Same filmmakers, similar storyline. In Act I of The Matrix, Neo is chosen, as The One, to undergo a test. He is pulled from his world and shown “reality.” In Act II he undergoes rigorous training, all the while doubting that he is, in fact, The One. In Act III, a crisis emerges and he must face his destiny, face his oppressors, prove his worth and emerge, triumphant, as The One. In V For Vendetta, Evey is not The One, she is Some Woman who gets into trouble one night. She does not undergo rigorous training, she gets brainwashed by a mysterious stranger who won’t take off his mask. And in Act III, a popular movement forms, but how much does that have to do with Evey’s actions?

The protagonist’s journey need not be heroic. Alex in A Clockwork Orange is an equal-opportunity thug, victimizing rich and poor alike, seeking nothing out of life but the opportunity to beat, maim, kill and rape. He’s motivated by the basest of human desires, but we like Alex because he’s pure; he’s smart and resourceful and he has a whale of a time. He enjoys his life. Society wants to take from Alex not only his opportunity to rape and kill but his desire to do so. As bad as Alex is, a society that would take away free will is seen as worse.

In Brazil, Sam has a clear goal, but has no idea how to achieve it. He gets jerked around a lot, cringeingly accepting indignity after indignity for a very long time. When he does finally rebel he is immediately punished so severely that he must retreat into a very long fantasy sequence. It’s also worth noting that Sam is not The One, but rather gains his role of protagonist quite by accident, when a fly falls into a telex machine, starting the narrative in motion.

Rollerball, interestingly, is a sports movie. The plot is the same as every boxing noir: the athlete just wants to play a good game but the powers-that-be want him to take a dive for the short-end money. It takes a very simple old story and puts it in a dazzling new context.

In Fahrenheit 451, Montag wants something clear and understandable, but thuddingly uncinematic — he wants to read. The enormity of that still hasn’t quite sunk in for me yet — a movie about a guy who’s only desire is to curl up with a good book. Rod Serling in The Twilight Zone knew that that’s no protagonist, that’s an antihero.

I’m off to have dinner with Mr. James Urbaniak, so I’ll leave this for now, but there is much more to be discussed here. Any information regarding the protagonists’ journeys of, say, Zardoz (which I haven’t seen) or Gattaca (which I haven’t seen in a long time) or any other movie not yet discussed is greatly appreciated.

The Prestige

Taking time off from my Futuristic Dystopia project to see a current release, and what could be more current than —

BATMAN VS. WOLVERINE IN 19th CENTURY MAGICIAN SMACKDOWN!

(read in complete safety! no spoilers revealed!)

Who will win in this titanic battle of magical superheroes? Batman’s got the skill, the ability to misdirect and the mastery of his dual nature, but Wolverine has mutant powers! He doesn’t have to put on a mask to do magic — he is magic!

Point for Batman — his character has thirty years on Wolverine, he’s acquired a lot of wisdom. Plus — he is the night.

Point for Wolverine — he’s got three blockbusters under his belt! Not to mention extra-super healing powers, an adamantium skeleton and retractable claws! Snikt!

But wait! What’s this, a femme fatale? Lovely Rebecca from Ghost World, twisting a spritz of highbrow, independent comics into the mix! Where do her loyalties lie? Only one thing is for sure in a movie about a superhero magician smackdown — nothing is as it appears to be.

Actually, one thing is for sure — 19th-century magicians are total dicks.

But watch out, there’s a ringer! Yes, that’s right, a plant in the audience! But who? Maybe it’s Batman’s butler, Alfred, or maybe it’s the guy from Labyrinth! He’s magic for sure! Hell, he might even be a space alien!

Exquisite in its production and complex in its construction, a thoroughly good time at the movies.

Truth be told, Michael Caine is probably here less to remind us of Batman and more to remind us of Sleuth, the premise of which could fit into any given five minutes of this movie.

Special mention goes to Rebecca Hall, as the Other Woman, who’s quite good and has not been in any big-hit movies. Go Rebecca Hall!

And the lovely and talented David Bowie is also quite good here. Bowie has most often been used as an effect in most movies, stunt-casting, but he gives an honest-to-goodness performance here, unflashy, controlled, subtle and sad. He also does for The Prestige exactly as he did for The Venture Bros — create an environment where it seems that anything could happen.

The screenplay, which is devilishly constructed, cheats, twice. There is one highly unlikely coincidence and one big fat made-up lie. But unlike, say, Vanilla Sky, this movie uses its big fat made-up lie to say something interesting and worthwhile about its time. Saying more than this would give away the game.

If folks would like to discuss the many spoilable things in the movie, perhaps we could do so below the fold. But that may be too immodest.

Fahrenheit 451

WHAT DOES BIG BROTHER WANT? Big Brother wants people to be happy, and books don’t make people happy. They are filled with lies, made-up stories, silliness, sophistry and fake drama. Why do so many people insist on being unhappy?

WHAT DOES THE REBEL WANT? Montag (Oskar Werner) burns books for a living. He’s comfortable and respected, but he is also is bored and mopey. He craves intellectual stimulus. His wife, Julie Christie, is a babbling idiot and the TV is filled with political fiction, propaganda and nonsensical gibberish. He finds his desired stimulus in the form of sexy neighbor Julie Christie (again with the sexy neighbor — if there were not attractive women in futuristic dystopias, there would never be any rebellion at all!) and, less cinematically, in the pages of Charles Dickens. When that turns out to be asking too much, he wants to get out of town and keep the literary flame alive.

WHAT DOES THE REBEL GET? A whole heap of trouble.

DOES THE SOCIETY CHANGE THROUGH THE ACTIONS OF THE REBEL? Not to any measurable degree. But the protagonist does find a way to rebel that has some positive effect and yet adheres to the letter of the law. Wait — the rebels want to adhere to the letter of the law — and that’s their brilliant idea? What the hell kind of movie is this?

NOTES: Handsomely produced and well-intentioned, it’s hard to get excited about this movie. There is no drama or conflict to its argument, there is no “other side” to it — who would make a movie promoting the burning of books? This is not to say that there should be an “other side” to a movie about totalitarianism, but even The Matrix allowed that there would be some people who would be happier living in pink goo with an electrode in their brain.

Wait a minute — why are some of the day’s leading cinematic lights making a movie that encourages people to spend their time reading books? Obviously the position of film in the minds of the world’s teenagers was in a much more secure position at the time.

Truffaut (wait — this lumbering, earnest, dour, leaden, humorless, stilted movie is directed by Francois Truffaut? [author shakes head vigorously, Bugs-Bunny style]) itseems, made this movie about reading books in order to indict what he saw as a greater evil — not book-burning or totalitarian government but television. One day, mark my words, there will be a video game about a society intent on destroying films.

The occasional sparks of cinematic interest, like subtle use of backwards-motion and the dead-end double-casting of Julie Christie as Idiot Harpy/Sparkling Intellectual don’t do much to raise the pulse of this movie. Its heart is in the right place, it’s just not beating very strongly.

By the end of the movie (spoiler alert!) Montag’s wife has left him, he’s burned his supervisor alive and he’s on the run from the law. He finds a commune in the woods (commune in the woods!) where the people memorize books in order to keep them alive until the dark ages lift. I always liked that idea, a little community where each person’s job would be to memorize a book. I always felt that if it came down to it, I would pick Samuel Beckett’s Endgame.

Brazil

WHAT DOES BIG BROTHER WANT? I’ve seen this movie a number of times and you know? I’m not sure. They seem to want to maintain the status quo, through a gigantic, inefficient bueraucracy. Citizenry is not controlled per se, but they certainly are kept in their places through this massively inefficient system that makes it impossible to get anywhere or do anything.

WHAT DOES THE REBEL WANT? Like Winston Smith and THX-1138, Sam wants the embrace of a good woman, in this case Jill, literally the woman of Sam’s dreams. Beyond that, Sam, spectacularly, has no plan; once he gets his mitts on Jill he is completely at a loss and must think fast to improvise a plan. And Sam’s just not that good an improvisor.

WHAT DOES THE REBEL GET? Oh, it doesn’t end well for the rebel.

IS THERE AN UPPER CLASS, AND DO THEY HAVE ANY FUN? There is and they do, although their fun is occasionally interrupted by “terrorist attacks” (which are never explained) and botched plastic surgeries. But even the upper class gets bossed around by waitstaff and bueraucrats and, this being England, everyone is terribly afraid of what others think of them.

DOES THE SOCIETY CHANGE AS A RESULT OF THE REBEL’S ACTIONS? In his dreams.

NOTES: Strangely, Jesus Christ is a major character in both this movie and in THX-1138. I’m not sure why. It doesn’t make sense for an oppressive dictatorship to choose Christianity as a state religion, as it does in THX, and whatever metaphorical connection there is to the narrative of either film eludes me. Neither THX nor Sam are particularly Christ-like; they confront no authority and are not sacrificed for the sake of publicity. They stand for nothing outside of themselves. I think the Christmas motif running through Brazil is there to emphasize the hypocrisy of the society’s priorities, but again I’m not sure. Strangely, in Sam’s dreams (however much of the movie those constitute) one of the symbols tossed on the rubbish heap by the robot samurai is a neon cross. So it seems like the movie is saying that the evil bueraucracy that Sam fights against is trying to destroy, among other things, Christianity. Is Gilliam pro-Christianity or anti? After Life of Brian I would have guessed anti (Christianity, not Christ), but here he seems to want to make some distinction between Christ and society’s perversion of the Christ message.

I love the idea that everything in the movie happens because there’s a guy running around out there fixing people’s heating problems without the proper paperwork.

One question that haunts me is, are there terrorists at all, after all? If not, who’s blowing stuff up?

Another question is, where does Sam’s dream begin? Does it begin at the start of his torture session, or much earlier?

Terry Gilliam’s movies are generally filled with Gilliamisms, but they are here this time in full force: the fish-eye lenses, the overstuffed production design, the imaginative, extensive use of miniatures, the sets a little too small to contain the action.

The acting is generally strong in this movie with Katherine Helmond a particular standout, but I gotta say, Michael Palin is freaking amazing. I’ve always been a fan, but his performance here as a polite, efficient, paternal torturer is just astonishing. Plus, for my personal delight, there are no fewer than than three strongly Steven-Rattazzi-like actors in this movie: Jonathan Pryce, Ian Holm and Bob Hoskins, all of whom Rattazzi has been compared to in his career (strangely, with usually the word “Pakistani” appended, as in “Steven Rattazzi resembles a Pakistani Ian Holm in his role in Cymbeline,” this about a man named Rattazzi). Terry Gilliam should just have Rattazzi play all the male roles in his movies and be done with it.

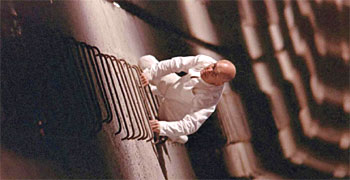

THX-1138

WHAT DOES BIG BROTHER WANT? Not much — total control of all human behavior, including thought, emotions and sexual response.

WHAT DOES THE REBEL WANT? The rebellion starts, as rebellions will, with sex. That was Winston Smith’s problem and it’s THX’s problem too. He’s willing to risk it all — the steady job at the police-robot factory, the mood-enhancing meds, the beige, block-like food, the holographic porn, the masturbation machine, for the embrace of a good woman.

WHAT DOES THE REBEL GET? He gets thrown in prison. At least I think it’s prison. It doesn’t act much like a prison. Things are kind of left open-ended in this movie, even prison. In any case, with the help of a hologram come-to-life (shades of Agent Smith) he escapes.

IS THERE AN UPPER CLASS, AND DO THEY HAVE ANY FUN? It doesn’t seem like there’s anyone in charge at all, just a series of interlocking bureaucracies that just kind of muddle through each crisis as it comes along.

DOES THE SOCIETY CHANGE AS A RESULT OF THE REBELS ACTIONS? No. In fact, as it develops, it is this society’s inability to bend its rules even a little bit that allows THX to finally escape.

NOTES: This is the Futuristic Dystopia boiled down to its barest bones. The narrative is kept at ground level — well, the sub-basement level, actually. Observational/behavioral in the extreme. There is no explanation of why this society is the way it is, or why THX’s mate is unhappy, or how a hologram comes to life, or how THX escapes from prison. The rebel doesn’t want to change things or seize control of the state or bring down Big Brother, he just wants to get the hell out of there (and even then it takes him more than half the movie to come to that decision).

It’s almost as though this is a prison-break movie made for the entertainment of the citizens in the city in the movie. In fact, it would have been a cool ending to have the last image, then have that flicker off and see that, all along, we were watching a movie being watched by a beige-block-munching pair of folks in their white suits, and the male turns to the female and says “That was nice” and the female says “Yes, a good fantasy” and they turn off the light and go to sleep.

Another cool ending would have THX climbing up to the surface,opening a hatch and finding himself on the surface of the Death Star. Or in the middle of the street in Modesto in 1962 as Paul LeMat races with Harrison Ford.

Or in the middle of a 19th-century village that turns out to actually be a 21st-century village — where everyone who lives there is actually a ghost.

The Futuristic Dystopia

Everything is perfect in the future. Everyone is happy, everything works. The authorities have everything all figured out. Nothing can possibly go wrong.

Or can it?

Half-brother to the End Of The World movie, the Futuristic Dystopia movie tends to follow certain perameters.

It’s hard to be a leader in a Futuristic Dystopia. There are always Rebels who suddenly see the society for what it is. Once these malcontents have had their realization, they must either fight or flee, or both.

Things aren’t so good for the rebels, of course. Everyone’s after them, and chases tend to ensue. Often they must have their heads put in uncomfortable apparatuses.

As one can see from the above examples, the Nixon era was a good time for Futuristic Dystopias (Brazil and the unpictured Blade Runner dating from the close-cousin Reagan era). Sensors indicate that the genre is due for a revival (Minority Report being a good example of this).

The Omega Man

THIS IS THE WAY THE WORLD ENDS: Germ warfare gets out of control, kills everyone.

SYMPTOMS: Charlton Heston is the Last Man on Earth. Except, of course, for everybody else.

WHAT ARE WE GOING TO DO ABOUT IT? Heston is content to live out his remaining days driving fast cars, shooting creeps with a high-powered weapons, playing chess by himself and watching the movie Woodstock every day. Others would prefer he die. Still others see in him some measure of hope for the future. It’s tough gig, being Last Man on Earth, everybody wants something from you.

WHO ARE THE BAD GUYS? The pale-faced, black-robed, light-sensitive, technology-hating, medieval-thinking goons who want to kill Heston and end all human life on Earth are led by, of course, a broadcast journalist. Then as now, they only wish to destroy.

NOTES: The movie is directed by Boris Sagal, veteran TV director and father to Katey. The only other film of his that I’ve seen is the similarly apocalyptic Elvis Presley vehicle Girl Happy.

Big problem: the bad guys here aren’t very scary. Or very interesting. Metaphorically they make “sense” (creatures who can’t tolerate light dress like the Spanish Inquisition, talk in fake medieval-speak and want to destroy all of humanity’s accomplishments), but they’re weak, disorganized and laughably inadequate to the task of being frightening or threatening.

The irony of Heston defending civilization’s greatest accomplishments against backward-thinking zealots (at the barrel of a high-powered assault weapon) while watching Woodstock every day and making whoopee with a hip, sassy black chick is not lost on me.