Brice Marden

Brice Marden, America’s greatest living painter, has what I believe is his first full retrospective of his work showing at MoMA right now through mid-January.

If you care anything about abstract art or American painting, or if you have a soul, I encourage you to see this show.

Yes, that’s right, when I’m not dissecting TV shows, writing movies about talking bugs or watching movies about futuristic utopias, I can often be found strolling about the world’s institutions of modern art, searching for dramatic collusions of lines and colors.

I was not always like this. I used to think abstraction was a fraud. I didn’t “get” it, I thought the artists were either delusional, working under an exaggerated or even fabricated sense of their own importance, or else laughing at us as we gazed in confusion at their messageless works.

Brice Marden changed all that.

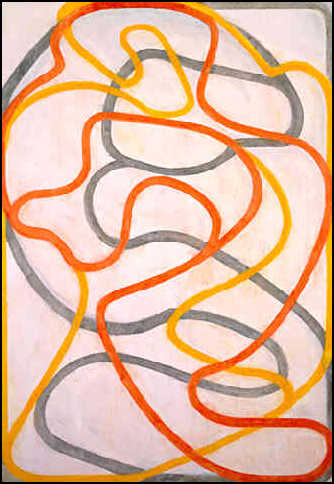

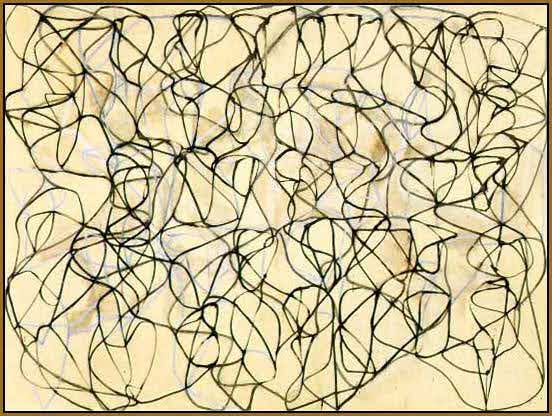

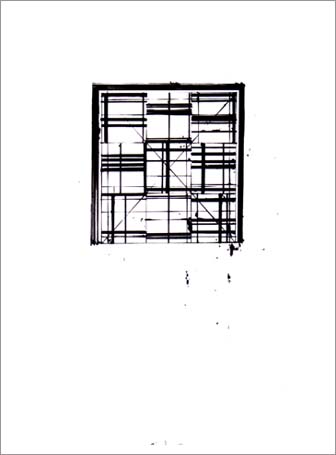

I still remember quite clearly when it happened. About 10 years ago I was in Cambridge with my bride-to-be and I stopped in at the local art joint to see a couple of Sargents they had on display. I never got as far as the Sargents because there was a show of Brice Marden drawings on the first floor. They were opaque and confounding, yet lyrical and intriguing at the same time. They were, I found out, drawn with anything but a pen — Marden will use twigs or shells, dipped in ink and held at a distance, to keep his line naive and undisciplined — and utterly bewitching. They looked like trees or vines or hedges or something, but they were both that and not that; they were both representative of things and also just marks on paper. And suddenly I “got” abstraction. In fact, I suddenly understood what the word “abstraction” means.

And the floodgates were opened. Suddenly I “got” Pollock and DeKooning, Sigmar Polke and Gerhard Richter, Barnett Newman and Cy Twombly (O! Cy Twombly — for added value, there are also a half-dozen crucil, essential Cy Twomblys hanging in the Big Gallery space at MoMA). And I went from being a guy who thought abstraction was a fraud to being a guy who now can barely tolerate representation — I keep thinking a representational artist is trying to sell me something. And now I’m the kind of guy who drags reluctant friends and family to places like the Dia Center in Beacon NY to see Richard Serra’s Torqued Ellipses (I’m still cursing myself for not getting to Houston for the Twombly show a few years ago). Now I’m the kind of guy who stops to look at a crack in the sidewalk or a badly-painted wall or a carelessly-whitewashed window. For me, a painted surface is now filled with light, a line brings in drama and a whole bunch of lines, artfully arranged, can produce an almost unbearable tension.

You may hate the Marden show. When I was there today there were plenty who did. Galleries were dotted with confused middle-aged women and disgusted middle-aged men, wavering between not being sure if they were being conned and utterly sure they were being conned. The men were particularly angry about it, sniggering to each other, voicing their moral superiority, muttering threats to the artist and, in one case, even wishing him a violent death. I’m not sure what provokes a reaction like that, I don’t know what one is expecting when one comes to the Museum of Modern Art. It seems to me that someone who sees a show as positive, life-affirming and glorious as this and reacts with a wish of violence upon the artist probably shouldn’t bother walking into an art museum in the first place.

UPDATE: Thanks everyone for writing in. For the folks who hate this stuff, let me reiterate, I used to hate it too. Now I don’t and this guy is the reason. I’m not an art historian, I’m not a theoretician and I’m sure as shootin’ ain’t no elitist. He opened up a whole new artistic world for me and I’ll never forget it.

And for those who like this stuff, here’s a few more. Thanks again!

Gattaca

WHAT DOES BIG BROTHER WANT? Well, there is no “Big Brother” per se, but society wants perfection, and it knows how to get it.

WHAT DOES THE REBEL WANT? Same as anybody, to go into space. I think “space” here represents “heaven.” The protagonist has been damned by unfortunate birth to hell; he’s going to fool the gatekeepers of heaven into letting him slip by.

WHAT DOES THE REBEL GET? With the aid of an unfortunate perfect-guy (who condemns himself to flames of perdition just as the protagonist is lifted into heaven), plus the love of a beautiful woman (nothing, NOTHING is accomplished in a Futuristic Dystopia without the love of a beautiful woman), plus the last-minute good will of a company doctor, he gets his wish.

DOES SOCIETY CHANGE AS A RESULT OF THE REBEL’S ACTIONS? Revolution isn’t really the protagonist’s goal here, and not even escape really. He wants to belong; he wants to know he’s good enough to go to heaven. The screenwriter chose the term “Valid” for a reason.

NOTES: The theme of the movie, it seems to me, is Will. Does the protagonist have sufficient will to achieve his goal? Does he have what it takes to overcome his genetic predisposition, switch identities with another guy, keep up the ruse for years, endure loneliness, constant, obsessive vigilance in cleanliness, break his own legs, live with Jude Law?

The fimmakers face a problem, of course: genetic science and astrophysics are dull, cerebral subjects. How to juice up the narrative and compel audience interest? MURDER! MURDER MOST FOUL, that’s how. And so, on his way to the stars, our protagonist gets caught up in a murder investigation that seems important only to the police. Indeed, no one seems interested in or excited by anything in this sterile, unpopulated future; to be excited, I suppose, would be to be less than perfect, which everyone is, or pretends to be.

Our protagonist is totally obsessed, to a ridiculous degree, with getting to the stars, and yet, with days to go before launch and a murder investigation breathing down his neck, he decides to take a chance in romancing Uma Thurman. This in spite of the risk of exposure, the unhygenic quality of sexual contact, the possibility of getting “girl germs” and the fact that Uma doesn’t seem to have much of a pulse. Perhaps he feels that if he can’t reach the stars in heaven he can at least have one in his bed on Earth.

Then, cleared from his murder investigation, given a clean bill of health from his corporation, and ready for launch, the protagonist must still face down his brother/detective for one last suicidal swim. Boys, as the saying goes, will be boys.

One of my posters pointed out in the previous entry that the society of Gattaca is filled with genetic flaws despite science’s best efforts, but I’m not sure that’s what the movie is trying to say. There is the usual assortment of Valids and In-Valids in society it seems, and they all seem to get along okay, although the Valids seem to lord it over the mutts a little bit. There is the six-fingered pianist, but it’s unclear from the script whether the pianist is a genetic freak or a planned accident — that is, is he another kind of outsider, like the protagonist, an In-Valid who has overcome his genetic deformity to find a place in Valid society, or did his parents actually give him six fingers on purpose so that he could become a great pianist? “That piece can only be played with six fingers,” says Uma, indicating that the piece in question was composed specifically for someone genetically modified.