Two New York stories

One of the baffling contradictions of New York is that so much of its economy is service-based and yet service there is so desperately bad. You go to the drug store to get a candy bar and when you finish the transaction the cashier does not thank you, you thank the cashier. You thank the cashier because the cashier refrained from killing you. There will be three bodegas in a two-block stretch, which under normal circumstances would create an environment of healthy competition for customers, but the service in all of them will vary from casually listless to downright hostile.

Read more

Notes from a visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC, part 2

The Met has a ginormous selection of Greek and Roman artifacts. What I don’t know about Greek and Roman artifacts would fill a museum, one even larger than this. But the stuff on display is intriguing so I wade in. Funeral urns, columns, lots of statues of soldiers and boys and ladies, all naked. Glass cases full of cups and bowls and signet rings and necklaces and stick-pins and cutlery and weapons and plates and all manner of stuff, going on forever. It’s a morass.

Read more

My list of over-seen masterpieces

Thanks to everyone who has answered the call of my earlier query. Many excellent ideas have been put forth and I encourage further thought on this.

Here is a list I compiled while leafing through Sister Wendy Beckett’s history of painting. It is all “usual suspects” and is intended to weed out the over-seen.

Van Gogh: Self-Portrait, Starry Night (above), Sunflowers, The Artist’s Bedroom

Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (see previous entry)

Rembrandt Self-portrait

Picasso: Guernica, Old Guitarist, Three Musicians, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon

Munch’s Scream

Dali: Persistence of Memory

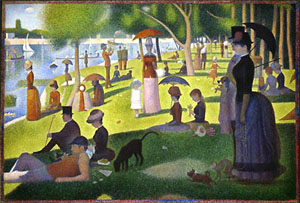

Seurat’s La Grande Jatte

Head of Nefertiti

Greek discus thrower

Rodin: The Kiss, The Thinker

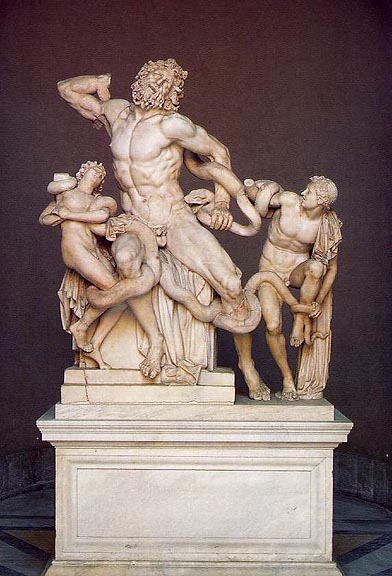

Lacoon and His Two Sons

Gutenberg Bible

First Folio

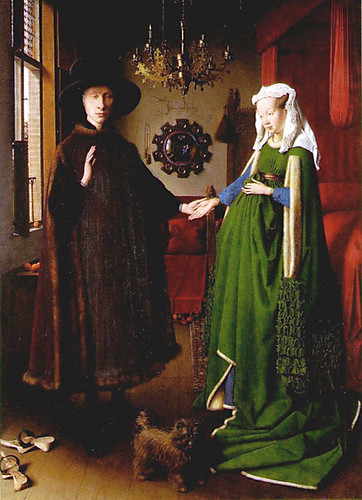

Eyck’s Arnolfini Marriage

Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights

Davinci’s Universal Man

Breugal’s Tower of Babel

David’s Death of Marat

Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring

Gainsborough’s The Blue Boy

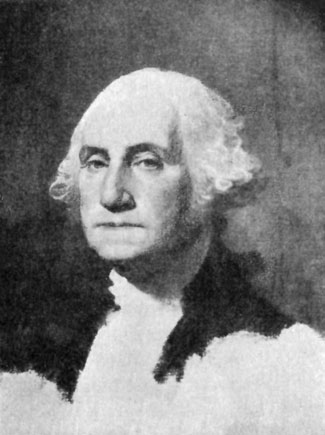

Gilbert Stuart’s Unfinished Portrait of George Washington

Ingres’s Grande Odalisque

Goya’s May 3, 1808

Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa

Whistler’s Arrangement in Black and Gray: the Artist’s Mother

Wood’s American Gothic

Manet: Le Dejeuner sur Herbe, Bar at Folies-Bergere

Monet: Waterlily Pond

Klimt: The Kiss

Brancusi: The Kiss, Bird in Flight

Rousseau’s Sleeping Gypsy

Warhol’s Gold Marylin

Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie

Matisse’s Dance

Magritte’s Apple-face guy (already taken by Thomas Crown, I’m afraid)

Giocometti’s Walking Man

Reinhardt’s Abstract Painting #5

Rauschenberg: Monogram, Canyon

Lichtenstein: Whaam!

Degas: Prima Ballerina

Renoir: Le Moulin de le Galette (God I hate Renoir)

Cezanne’s Fruit Bowl, Glass and Apples

Robert Indiana’s Love

Jasper John’s Three Flags

Then there are a handful of 20th-century guys who don’t really have one standout work (at least not in popular consciousness) but who’s stuff would be recognized as a type: Rothko, Pollock, Calder, De Kooning, and to some extent Warhol.

Query

For instance.

For a television show I’m developing, I request your favorite instantly identifiable cultural artifacts. “American Gothic,” “The Mona Lisa,” “Guernica,” “Starry Night,” that level of media saturation.

The point of this exercise is to find works of art that anyone at all would recognize and understand to be valuable cultural landmarks. I have a running list of my own but I’m curious to see what others come up with.

Oh, and one other thing: the artifact must be portable, which leaves out DaVinci’s “Last Supper,” the cathedral of Notre Dame and the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Points awarded for not being blindingly obvious.

The artifacts selected will be made into maguffins in order to drive a mystery narrative.

Let me hasten to add that the artifact need not necessarily be an artwork. It could be a cultural artifact of another sort. Just as everyday Greek tableware items from ancient times are now considered precious antiquities and put on display in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (more on that later), what other museum-quality items could one present as a maguffin in a mystery narrative? Say, the Liberty Bell, or the Wright Bros airplane.

Notes from a visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC, part 1

Greeks: excellent

Romans: excellent

Etruscans: meh

Cypriots: ugh

Persians: I don’t get it

Egyptians (pre-Rome): A plus

Egyptians (post-Rome): B minus

Rembrandt: good

Vermeer: good

Ingres: good

Goya: okay

Van Gogh: good

Gauguin: okay

Sargent: good

Degas: good

Renoir: sucks

Homer: meh

Eakins: okay

Remington: beneath contempt

Another long, awkward elevator ride

INT. ELEVATOR — NIGHT

Ingmar Bergman and Michaelangelo Antonioni ride in (what else) silence.

IB. Mm.

MA. You with the whole “is there a God” thing, me with the whole “existential angst” thing —

IB. Mm.

MA. And here we are.

IB. Here we are.

Silence.

MA. What was it finally did it to you?

IB. Mm?

MA. ‘Cos we both got up there, man, you know? 80s, 90s, I mean, that’s a load of years for a couple of guys who made such a big deal out of how miserable life is.

IB. Mm.

MA. Me? That Chuck and Larry movie. I saw that, I just said “forget it, I’ve had enough, I’m out of here.” Billy Madison was cute, but I drew the line on Sandler with The Waterboy. What about you?

IB. Me, oh, you know me. The weight of a Godless world, the the suffocating oppression of memory, the haunting terrors of family.

MA. I gotcha, sure.

IB. And Transformers.

MA. Ooh, yeah, that one hurt.

IB. I’m like, “what, I expanded the vocabulary of cinema to explore the most important, penetrating questions of the human condition so that monster robots could fight each other?” Give me a break.

MA. I totally get you.

Silence.

IB. By the way, I’ve always wanted to tell you —

MA. Yes?

IB. I hated Zabriskie Point.

MA. Oh yeah? Well I hated The Serpent’s Egg.

IB. You —

Silence.

IB. Ah, the hell with it.

Silence.

MA. Jesus, this is one long elevator ride, isn’t it?

IB. You ain’t kidding.

MA. Did you, when you got on, did you happen to notice which way it was heading?

IB. Well, I assumed —

Pause. They look at each other.

The elevator dings. The doors slide open. Bergman and Antonioni go to step out, but TOM SNYDER steps in.

TS. Hey, Ingmar Bergman! Michaelangelo Antonioni! Good to see you!

He slaps them on the back. They look distinctly uncomfortable.

TS. Boy, this death thing, this is wild, isn’t it? I tell you, I wasn’t ready for this one. Reminds me of the time I was taking a train to Bridgeport once, I was in the station, and you know how they’ve got those newsstands, right? Where they sell all the newspapers and candy and whatnot. And there’s a shoe-shine guy next to the newsstand, right? And I’ve always wondered about the shoe-shine guy. You know? Who is this guy? Is this what he wanted to do with his life? “Shoe-shine guy?” Has he reached the pinnacle of his career? “I am a shoe-shine guy?” And he’s got this hat, it’s kind of like a conductor’s cap, almost like maybe a conductor gave it to him, like you know, maybe this guy’s a little “simple,” you know, and one of the train conductors took pity on him and gave him a hat, you know, to cheer him up, make him feel like he’s part of the team. Anyway, so I’m there in the train station and this skycap goes by, huge stack of luggage on one of those rolling things, what are those things called, dollies? Not dollies, but like a dolly, with the handle, you know? And I’ve always wondered, who decides whether the cart gets a handle or not? And —

Bergman and Antonioni wither as Snyder chats on and on. Fade out.

Close Encounters pop quiz

Q: Farrah Fawcett has a cameo in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. In which scene does she appear, and where?

Movie Night With Urbaniak: Close Encounters of the Third Kind

There are movies and there are movies.

I’m a Spielberg fan. I’ve been a Spielberg fan for a long time.

How long have I been a Spielberg fan? I’ll tell you how long I’ve been a Spielberg fan, smart guy. When Duel came on the television machine in 1971 and I was ten years old, I remember I wanted to watch it because it was directed by the guy who had made a Columbo episode I really enjoyed (which IMDb tells me was broadcast a mere two weeks earlier.)

I loved Jaws, it changed my life, no doubt about it, but my confidence in Spielberg as the leading director of his generation was already well in place in my mind by the time Close Encounters opened in theaters, Christmas 1977.

I was, at that point, a 16-year-old usher who had just gotten a job working at what had once been a vaudeville house in the suburbs of Chicago. The first movie during my tenure there was Close Encounters, so I was blessed to see this movie thirty or more times in its initial run, with a crowd every night, and it never got old, never wore out its welcome, never seemed like anything less than an event. A symphony.

The truck on the lonesome highway, the police-car chase, the perfectly-observed scenes of casual suburban squalor, the attack on the country house, these are scenes I would race to the theater to watch over and over, marveling at them anew each time. I’ll tell you: I knew from the first that Close Encounters was great cinema, but somehow it’s never felt to me like Close Encounters was “show business.” I always felt, from the very beginning, and this goes for a lot of Spielberg’s movies, that I was watching something that transcended “show business,” that I was in the hands of a true believer. It hit me relatively early on that Close Encounters was a deeply religious movie, and the notion of godlike, benign extraterrestrials showing up and extending an innocent, questioning hand of greeting to our horribly wrong-headed world was one I found hugely seductive and almost unbearably moving.

God calls, and Roy Neary answers. God calls many people, but only Roy Neary has what it takes to push through all the bullshit in the world, the trappings of his stupid bullshit suburban family life, the chains of work, reputation and normality. Only Roy Neary has what it takes to answer the call, leave his life, make it through all the barriers that this awful world puts in his way (the government, who has also heard God’s call, desperately desires to exclusively control the discourse between humanity and the deity) and step up to the altar to be received into heaven. It’s a profound statement of faith, fortitude and perseverance.

I have no idea how it plays now. I’ve watched it so many times it barely feels like a narrative tome any more, it flows so naturally and so effortlessly. I can see the craft and care put into it, but I also still get utterly lost in its most powerful scenes. One day, when I show it to my children, will they see the same movie I saw at 16? Or will they look at the clunky 70s special effects, the gritty 70s-realism acting and production design, the low-key, humanistic story line and be all like “o-kay, Dad, whatever you say, is it okay if we go upstairs and watch Transformers III again?” Will they have to wait until they learn a little something about film history before they will be affected by its rhythms, its layers of references, the purity of its soul?

Anyway,

and I watched it tonight over a bottle of pretty good wine and it was a blast. The air-traffic-controller scene toward the beginning of the movie, a scene that would be cut from any other movie today, stuck out for us immediately. I’ve always loved the scene and found it terrifically exciting, especially for a scene involving none of the principle characters, no special effects, and no on-screen confrontations. It’s a scene about a bunch of professionals talking on radios and yet somehow the tension is palpable. The acting in it is not only some of the best in the movie but some of the best in Spielberg’s canon. In a lot of ways, as Urbaniak mentioned, it’s hard to imagine Spielberg today directing that scene. It’s like a scene from All the President’s Men or something, all subtlety and nuance, the performances deriving their power from what the characters are not saying, not what they are saying. And the voice work of the radio voices could not be better.

Someone, I can’t remember who, once asked, regarding the opening scene, “Why doesn’t the UFO investigation team wait for the sandstorm to end before they go out into the field?” And it’s a good example of the pure cinema of this movie. The UFO investigators go out into the Mexican desert in the middle of a sandstorm because it makes a better scene — it creates pressure and urgency. These guys aren’t just investigating UFOs, they’re investigating UFOs in the middle of a sandstorm, which means they have to shout and cough and gaze in wonderment at things that appear mysteriously out of the sandstorm.

Compare this scene with the “Mongolia” scene shot for the otherwise-useless “Special Edition” from 1980. The Mexico scene in the original is weird, mysterious and deeply unsettling, the Mongolia scene is jokey, obvious, shot and cut in a completely different style, closer to an Indiana Jones movie in tone than Close Encounters. I like the idea of the scene but, basically, I can find no shot in the “Special Edition” that improves my understanding of Close Encounters and it gave me great heart to realize that Spielberg had expunged most of it for the current edition on the racks.

Now that I am sufficiently removed from Midwestern suburban life of the 1970s, I gaze upon the production design of Close Encounters with something approaching awe. The hell with the UFOs, I want to know who was responsible for the astonishing set-dressing of Roy Neary’s house. You can tell that Roy has gotten his “one room” to decorate, it’s the one with the milk crates stacked against the wall for shelving and the hobby crap piled up everywhere. But what about the rest of the house? All the tschotchkes and bric-a-brac, the Walter Keene painting over the piano, the ceramic chicken on the “good china” shelves, who picked all that out? Ronnie? She’s 30 years old, she picked out all that crap? How did she ever have the time? The house is full of crap, the stupid prints hanging in the bedroom, the ungodly wallpaper, the Snoopy poster in the boy’s bedroom, the mismatched glassware, the milk carton on the table at dinnertime, the casual blurring of personal boundaries, everything is absolutely godawful, everything is absolutely accurate, and everything is mounted with such great love and understanding of those characters and their world, and, best of all, it’s never pointed at by Spielberg. Spielberg never holds up these suburbanites as ridiculous, he loves these people and wants to capture their world with all the detail he can muster.