Another long, awkward elevator ride?

Perhaps, but man, dig that crazy sound.

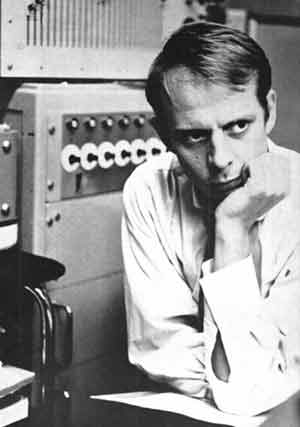

Karlheinz and Ike, two great 20th-century composers, rest in peace.

Crass commercialism

You’ve seen him write about movies, maybe you’ve even seen his movies, now you can own his movie memorabilia!

It’s occurred to this writer that his children are not, in fact, going to educate themselves, and all the toys he bought as a carefree, spendthrift, childless movie nut would now be better turned into cold hard cash. Starting with this handsome Godzilla toy from the ill-regarded 1998 release. Matthew Broderick not included.

If you are interested in obtaining this crucial piece of pop-culture history, or if you just want to read this author’s pithy description of same, here’s your chance.

And here‘s another!

Star Wars: Episode VII — the treatment, part 1

My son Sam (6), if I haven’t mentioned it before, loves Star Wars. He’s watched all six of the movies numerous times (Episode III is his favorite, followed by Episode II), owns over a hundred action figures (many of them hand-me-downs from Dad) draws pictures of the characters every chance he gets, and has recently completed a movie (which Dad is now editing — it has, I’m afraid, many longueurs). It was inevitable that he would turn to writing scenarios for imaginary Star Wars stories. I don’t have the heart to tell him that he could probably make good money at doing this work.

Tonight’s bedtime conversation:

SAM: Dad?

DAD: Yes?

SAM: You know what would be better?

DAD: What would be better?

SAM: If, at the end of Episode IV (A New Hope, or Star Wars, to peopleover 30 years old), if instead of Luke Skywalker shooting a photon torpedo into the Death Star? If instead he shot down a TIE Fighter and the TIE Fighter crashed into the exhaust port instead and set off the chain reaction.

DAD: Yes. You are correct, that would be better.

SAM: And in Episode VI (that is, Return of the Jedi)?

DAD: Yes?

SAM: Well, actually, Episode VI is good the way it is.

DAD: You think so?

SAM: Yeah. Except —

DAD: Except?

SAM: It would be cool if, instead of the rebels blowing up the reactor in the middle of the Second Death Star? If, like a million Star Destroyers and Super Star Destroyers crashed into the Second Death Star.

I cannot tell you how much these little conversations make my heart burst with pride.

As a service to my loyal readers, allow me to offer a version of this story with proper spelling, punctuation, and a few small textual notes:

1)”As the second Death Star explodes, the Dark Trooper arrives in a TIE Fighter at a Battleship, with lots of Troopers. There is a menace named Darth Black.”

NOTES:

The “Dark Trooper” is a reference to the bad guy of the unplayably outdated video game Star Wars: Dark Forces. Sam has never played this video game, but he does have an action figure of the Dark Trooper, who looks like this:

By “Battleship” he is referring to a Star Destroyer. “Darth Black” is not a typo but a new character, a heretofore uncelebrated Sith lord.

Sam completed the first page of this story after school one day and was hugely excited by it, as was I.

SAM, pen in hand: What should I write next?

DAD: Well, what happens next? It’s the end of Episode VI, the second Death Star has just exploded, that’s a great beginning. Now I see you’ve got a Dark Trooper who survived the explosion. That’s also a great idea — the Empire has just collapsed, the Emperor is dead, but there are all these millions of soldiers who worked for him — what are they going to do? What are their loyalties? Are they being hunted by rebels, do they form their own army, what do they do? And here I see you’ve got a new character, this Darth Black — what does he want? What makes him a menace? And who’s saying he’s a menace? A menace to whom?

SAM, visibly distressed: Just tell me what to write…

And then, moments later, he was off again, no help needed from me. And, as you will see, he utterly ignored every helpful suggestion I made, a decision that makes my heart sing. (I have since learned that, when he wrote the first page, he didn’t actually know the meaning of the word “menace.”)

2) “As, waiting, Darth Black calls the Imperial Spy. All troopers are in position, and as the Imperial Spy sets up his troopers, a figure arrives in the distance.”

As the proud father, I note that Sam has already mastered the technique of always pitching a story in the present tense. I also note, with some interest, that he begins two pages in a row with the word “as.”

The geography of these scenes, however, is confusing, and doesn’t get better. I think the Imperial Spy and Darth Black are on two different space ships, but I could be wrong.

The “Imperial Spy,” for those who don’t speak Star Wars, is this guy:

A minor character from Episode IV, without any proper dialogue, he has nonetheless captured Sam’s imagination. You never know what’s going to do it I guess.

3) “It was Qui-Gon Jin. The Imperial Spy saw his lightsaber was red. He went up to the Imperial Spy. He [stood] there. The Imperial Spy called Darth Black.”

Qui-Gon Jin, of course, died at the end of Episode I. His appearance here, therefore, counts as a major revelation. Close readers will note the color of his lightsaber — only Sith’s lightsabers are red.

At this point, I had to ask what Darth Black looked like. Sam replied that Darth Black was the brother of Darth Maul, had the same horns growing out of his head, and had black skin. I imagine him having the same kind of wild face-decoration as Darth Maul (that is, I think it’s a decoration) but in a kind of black-on-black pattern instead of red-on-black, which, I’ve got to admit, is a whole lot more cool.

4) “Suddenly Rebels [a]re surrounding the two figures [by which I think he means Qui-Gon and the Imperial Spy]. They [take] out their guns. Suddenly, Qui-Gon jump[s] up in the air and kill[s] all the rebels. He [is] a good fighter. He [Darth Black] [is] impressed.”

I have to say, for a six-year-old, having the red lightsaber pay off with a stunning plot twist of Qui-Gon turning out to be evil, is truly inspired.

5) “Darth Black heard about the Jedi [that is, had heard of Qui-Gon Jin, and, by extension, knows that he is supposed to be dead]. He calls him over [calls who, and from where, is unclear]. The Imperial Spy got in his ship. The Jedi [Qui-Gon] snuck in after him. He flew to the battleship [the same battleship as the Dark Trooper?]. He got out. The Jedi snuck out too. He [the Jedi, Qui-Gon] explored. Someone saw him. He [the someone? The Imperial Spy?] [brought] him to Darth Black.”

6)”Darth Black ask[s] where they found him [that is, Qui-Gon]. ‘He was walking around’ [replies someone]. ‘Maybe he [is] the bad Jedi I[‘ve] heard about’ [says Darth Black]. ‘What Jedi?’ [asks the someone]. The Imperial Spy walk[s] past. He [sees them talking] [that is, he saw Darth Black talking to the someone]. Suddenly a ship arrived in the distance.”

Again, I’m a little confused about who Darth Black is talking to and what role the Imperial Spy plays in all this, but this much is clear: Qui-Gon Jin is alive, and evil, and he’s looking to join the ranks of a Sith lord who has, somehow, survived the collapse of the Empire. If you’ve got a better idea for Episode VII, I want to hear it.

Movie Night With Urbaniak: Heaven’s Gate (part 1)

As

is an actor of delicate constitution who requires his beauty sleep, we were unable to watch all 219 minutes of Michael Cimino’s legendary cinematic disaster in one go — we left off at the intermission and will pick it up again soon (the promise of a DVD screener of There Will Be Blood is the carrot, watching Heaven’s Gate is the stick in this relationship).

I rushed right out to see Heaven’s Gate when it opened in 1980 in a shortened version. I had seen The Deer Hunter several times in the theater and enjoyed it quite a bit and I was anxious to see what Cimino would do with a western. I had heard all the stories about his extravagant profligacy on the set (the budget was, reportedly, over $40 million) and, being who I was, I was pulling for the director. I had heard about the disastrous screening of the long version, I had read all the terrible, terrible reviews, I knew no one was going to go see this movie, yet I was there, first screening, opening day, hoping against hope that, somehow, everyone was wrong and some kind of unique, misunderstood masterpiece awaited me.

Well, that didn’t happen, but I still couldn’t quite bring myself to hate the movie. Being a mere wisp of a 19-year-old, I did not possess the relative understanding of story structure I do now, so I couldn’t quite put my finger on why the movie didn’t work. But I could not deny that much of it was beautifully rendered, and there was something weird and mysterious about its insistence on having nothing happen for long, long stretches of movie. And that was the short version.

Now that I’m a big-deal Hollywood hotshot, it’s easy to identify the movie’s problems, although it might not have seemed that way in 1979. Basically, there is a HUGE amount of atmosphere

and very little plot.At the two-hour mark, I found I could count the total number of plot-points covered on the fingers of one hand. This is, alas, not an exaggeration.

PLOT POINT 1: Kris Kristofferson graduates from Harvard in 1870. The statement of this fact takes up an astounding 23 minutes of screen time.

PLOT POINT 2: Twenty years later, Kris is a sheriff (I think — it’s unclear and the sound mix on the DVD is perhaps the worst I’ve ever heard — ambient background thunders in the speakers while actors in the foreground murmur beyond audibility) in Wyoming, where Big Doings are going down: corporate ranchers are preparing to go to war with poor immigrant farmers. The establishment of this plot point takes us another twenty minutes.

PLOT POINT 3: Kris is in love with a French prostitute. Getting this idea across takes, I’m not kidding, 30 minutes of screen time.

PLOT POINT 4: The poor immigrants may be poor, but they sure know how to have fun. This accounts for another 30 minutes, as we watch cheerful immigrants pose for pictures, juggle, roller skate, dance, have sex, play music, sing, stage cockfights, fight and swear and grin. As Urbaniak noted, it’s like the party scene in steerage in Titanic, but expanded a half-hour.

PLOT POINT 5: Chris Walken, a hatchet-man for the corporate ranchers, is also in love with the French prostitute, and intends to sue for her hand. This accounts for the final 20 minutes of screen time before intermission.

And that’s it. Honestly.

Now compare this to, say, the plot of Raising Arizona: The protagonist robs convenience stores, goes to prison at least three times, meets and falls in love with the police officer in charge of booking him, rehabilitates himself, asks her to marry him, moves in with her, settles down, tries and fails to start a family all before the title sequence begins. If Michael Cimino had directed Raising Arizona he would have spent a half hour just examining the daily activities of the convenience-store clerk.

It’s hard to watch this movie and not feel for the studio executives in 1980 — faced with this extraordinarily slow, almost-plotless story, it’s impossible not to think “well, they could easily trim this down and have a taut little western.” And yet, if you cut out all the impressive atmosphere (and a good deal of the atmosphere is truly impressive) you would not have a “taut little western,” you would have a slack, underplotted little western. Now, there was, once upon a time, room for movies that place atmosphere over plot, but not to the ridiculous extremes taken by Heaven’s Gate. I mean, Jean-Luc Godard is Steven Spielberg compared to Michael Cimino in this regard.

And yet, for some strange reason, the movie is not “boring,” exactly. It sustains interest, partly through its dense atmosphere, partly through its peculiarity — it’s novel, and even pleasurable in a certain way, to see a big-budget movie utterly unconcerned with forward momentum. Urbaniak says that it’s interesting without being dramatic, a sentiment I echo, and add only that the scenario is dramatic it’s just very poorly structured dramatically. You’ve got a bunch of evil ranchers who are hiring an army of gunmen to wipe out a community of immigrants, that’s an excellent start for a drama. But that plot point is not announced until minute 43, and nothing is done about that struggle for another hour of screen time. Kris Kristofferson hears about the rancher’s nefarious plan and heads off to the immigrant community to, um, to do, um, well, we don’t know what exactly he plans to do, but we know he doesn’t like the ranchers so we assume he is on the side of the immigrants. So he goes pouncing off to the immigrant community and immediately spends thirty minutes horsing around with his girlfriend.

The cast is large and capable and includes many actors who went on to become big stars, so that’s always fun. Most of the acting is decent enough (there is one scene where Kris Kristofferson and John Hurt square off in a billiard room, having a “barely audible growl-off”)

and some is quite excellent. Urbaniak adores Chris Walken in this movie, an appreciation I can’t quite share — his presence seems too modern, too off-center and not of-the-time. But I bow to his superior judgment in this regard. Sam Waterston, on the other hand, is just dreadful as the main Evil Ranch Guy. He struts, preens, glares and flares his nostrils as his forces gather around him, all to remind us that this guy is Evil. It seems to me that once the screenplay identifies you as the Evil Guy, the best thing you can do is As Little As Possible.

The sound mix is, as I’ve noted, abysmal, and the transfer is substandard — probably because they had to cram a four-hour movie onto a single DVD. The production design is sumptuous and absurdly detailed, without ever clearly showing where the $40 million went. The score is an embarrassment, it sounds exactly like the first idea pitched at the initial post-production meeting.

Oh, and the haircuts — why can’t they ever get the haircuts right? All the supporting players look appropriately 19th century, but every time a lead actor strolls on, it’s 1979 again.

Coen Bros: The Big Lebowski

“Your revolution is over! The bums lost!” images swiped from the excellent Coen resource “You Know, For Kids!”.

NOTE: I have gone over (not to be confused with “micturated upon”) the deeper meanings of The Big Lebowski once before — you may read my previous analysis here.

THE LITTLE GUY: The Dude is unique in the Coen universe in being a protagonist who is perfectly happy with his social standing. He does not seek money, betterment, achievement, a child, a mate, clean clothes or, really, anything besides a state of blissful intoxication. Anything he does he does because someone else is forcing him to do it. As the Stranger describes him, “he’s the laziest man in Los Angeles County, which would place him high in the running for laziest worldwide.” He’s not particularly interested in saving the kidnapped girl, recovering the stolen fortune or even defending himself from hoodlums. Even his desire to reclaim his soiled rug is something that his bellicose friend Walter puts him up to — if it were up to The Dude, his peed-on rug would be worth it just for the story to tell his bowling buddies.

(It’s also worth noting that, for all the time The Dude spends hanging out in a bowling alley, listening to bowling games of the past and fantasizing about bowling scenarios, we never actually see him bowl.)

Many dismiss, or praise, The Big Lebowski as a “shaggy dog story.” These are people with not enough time on their hands. Lebowski is a movie positively overstuffed with meanings, far too many meanings to be gleaned from a single viewing.

WHERE’S THE MONEY, LEBOWSKI? Let’s start with Lebowski’s brilliance as a detective story. Lebowski presents us with a Big Sleep-style mystery: What Happened To The Kidnapped Heiress? But the kidnapping plot, we eventually find, is a gigantic red herring. The real mystery in The Big Lebowski is Where’s The Money? This is not anidle plot-point, it is a key subtext to understanding the importance of the movie. The kidnapped girl is a worthless idiot of importance to no one, but the money, ah, the money, as Mose in Hudsucker would say, “drives that ol’ global economy and keeps big Daddy Earth a-spinnin’ on ‘roun’.” The Big Lebowski is a social critique disguised as a mystery disguised as a stoner comedy.

The key to understanding the social dynamics of The Big Lebowski is to always follow the money. So where is “the money” in The Big Lebowski? (“Where’s the money, Lebowski?” is, in fact, the movie’s first line of dialogue.) The Dude doesn’t have it — he lives in a crappy Venice bungalow and is late on his rent. His friend Walter has his own business, but doesn’t have any appreciable amount of it. Jeffrey Lebowski, despite appearances, doesn’t have it, and his wife Bunny obviously doesn’t have it. The Nihilists don’t have it and neither does Larry Sellers, even though Walter is positive he has it.

The joke is, of course, that no one has it — “the money” belonged to the first Mrs. Lebowski, who is long dead. We don’t know how Mrs. Lebowski got her money — “Capital,” the source of “the money” in The Big Lebowski, is nebulous and taken for granted. “The Money” is like “The Gold” in Eric Von Stroheim’s Greed — it’s not something to be earned, it’s almost a natural resource, something that’s just sitting around waiting for someone to figure out how to get it.

Who has any money in The Big Lebowski? Maud Lebowski, Jeffrey’s daughter, the aggressively “feminist” artist, has some money, but even that is not hers, it’s her mother’s. She hasn’t earned it and seems to be frittering it away on ugly art and an inane lifestyle (the other artist presented in Lebowski is The Dude’s landlord, with his stupefying Greek Modern Dance routine — art doesn’t seem to count for much in the Lebowski universe). The only other wealthy personage in Lebowski is Jackie Treehorn, the pornographer. So: in the world of The Big Lebowski, “Money” is represented by an embezzler, an heir and a pornographer — as harsh a critique of American capitalism as I’ve ever heard.

Everyone else is barely scraping by or actively losing money hand over fist. The indignities heaped upon The Dude in this narrative are great: his house is repeatedly broken into (“Hey, Man, this is a private residence” he lazily chides a trio of armed thugs), his possessions are smashed until nothing is left of them, his car is shot at, crashed, stolen, crashed again, peed in, bashed and finally set fire to. He is punched unconscious, drugged and hit with a coffee mug. The Rich in Lebowski get richer by soaking the Poor, and every transaction between social unequals is a heartbeat away from physical violence. Even Maud, who only wants her rug back, can’t resist using force upon The Dude in order to get what she wants.

(The other thing Maud wants, of course, is to conceive a child. This is a succinct reversal of the argument of Raising Arizona. In the earlier movie, Ed reasoned that the Arizonas [The Rich] deserved to lose a child so that she [The Poor] could have one. In Lebowski, Maud [The Rich] assumes that it is her right to use The Dude [The Poor] as a method to get her own child — in both movies, children are merely another expression of capital [or, as the Dude complains about pornographer Jackie Treehorn, “he treats objects as people, man.”)

THIS AGGRESSION WILL NOT STAND: “Aggression” is a big word in Lebowski. The Dude is, of course, the least aggressive person in the story, yet he invites aggression at every turn, from his friends, his bowling rivals, his various contacts in the mystery. The parallel is drawn to the Gulf War, and if there is a coherent critique of the Gulf War to be found in Lebowski (and I’m not sure there is) it could be better applied to our present situation in Iraq: in Lebowski, aggression is met with violent retribution — but it always falls on the wrong person. Jackie Treehorn wants his money, but his goons beat up the wrong Lebowski. The Dude’s rug is peed on, so he demands retribution from a complete stranger. Jeffrey Lebowski sends The Dude to identify the kidnappers as Jackie Treehorn’s thugs (he won’t take responsibility for The Dude’s rug, but insists that The Dude take responsibility for his missing wife), but finds they are completely different people (and gets his car shot up for his trouble). The Nihilists demand a ransom for Bunny, but cut off the toes of one of their own to prove their seriousness. Walter exacts violent retribution on Little Larry Sellers, but ends up bashing the car of a complete stranger.

This, I think, is the meaning of poor Donny’s death. In times of war, wealthy, powerful men make up their minds to be aggressive (Saddam against Kuwait, Bush against Saddam), but the people affected are always the poor and powerless, people who die without ever understanding what the true cause of the aggression was. In the case of the Gulf War, it was the Iraqi soldiers and civilians who sided with the US, only to be abandoned, in the case of Lebowski it’s poor Donny, who’s salient quality is that he never knows what the hell is going on and who dies, absurdly, of a heart attack during an attack by the Nihilists.

(This is also, I think why Walter compares Donny’s death to the troops lost in Vietnam, although Walter, to be fair, tends to compare everything to Vietnam. He compares Bunny’s kidnapping to Vietnam, he finds service in diners lacking due to his experiences in Vietnam. The Dude chides Walter for this habit, but Walter, I think, is on to something. Bunny’s “kidnapping” can be compared to Vietnam, insofar as it’s a mysterious act of aggression perpetrated by a wealthy man scheming to steal a ton of money and make a poor man pay for it.)

CRIME AND PUNISHMENT: The Big Lebowski presents the widest view of law enforcement in the Coen canon. While not as warm or good as the police in Fargo, the police in Lebowski could at least be described as cheerfully unhelpful. They laugh at The Dude’s problems for the most part, but they don’t actively seek to harm him and they are not shown to be in direct employ of the forces of evil.

That’s LA’s cops, obviously. Malibu is a different story — the sheriff in Malibu is a reactionary hothead, the fascist boot protecting the rights of a pornographer.

Jeffrey Lebowski lives, of course, in Pasadena — but we manage to get in and out of his community without a run-in with the police.

THE MELTING POT: Race and national origin always plays a significant role in the Coens movies, and Lebowski emphasizes this more than ever. Oddly, all the main characters are Polish-American. Donny is Greek, Brandt I’m going to say is a WASP, Bunny is Swedish, the Nihilists are German (as is the administrator for The Dude’s bowling league), Jesus Quintana is Hispanic (and a pedarast), the cops are racially mixed (as are Jackie Treehorn’s goons, and the casts of his porn movies), Maud’s friends are European (one might say “Eurotrash”), the poor owner of the Ferrari is Hispanic, the detective shadowing The Dude is Italian (as is Maud’s chauffeur, although Jeffrey Lebowski’s chauffeur is French). Maud’s doctor is Iranian, and The Dude gets thrown out of a cab driven by an African-American man who likes the Eagles. The only Jew visible is, of course, Walter, who isn’t really Jewish. I wonder if it means anything that the only character identified as Jewish (that is, Walter’s ex-wife) is out of town for the duration of the narrative?

What is the point of this rainbow coalition of characters? Is it merely a comment on the diversity of LA, or is the city in Lebowski meant to symbolize something bigger, the whole of the US, or even the whole of the world? Is Jesus’s florid aggression toward our heroes meant to be an analogue to Saddam’s aggression against Kuwait?

PANCAKES: Nihilist Uli Kunkel favors pancakes for a meal, just as Gaere did in Fargo. I can see no significance here except that “pancake” is a funny word. In The Ladykillers the protagonist favors waffles, which I think explains that movie’s miserable death at the box office.

Hulk To-Do List

Found this post-it note, as is, stuck to my refrigerator door one morning. Needless to say, between the color of the paper and the items listed, I could only come to one conclusion — The Incredible Hulk had left his to-do list in my kitchen for some reason.

(Turns out SMASH is an acronym for a Santa Monica school organization my wife needed to call — but I like my version better.)

UPDATE:

Coen Bros: Fargo

Fargo is a remake of Blood Simple, insofar as they are both crime dramas without protagonists. Oh, one remembers Fargo ashaving a protagonist, but it doesn’t really. What it has is a likable main character, which is a different thing from a protagonist, and is something that Blood Simple doesn’t really have. Marge, the pregnant sheriff, is but one-third of the three-pronged narrative of Fargo, and does not show up until the beginning of Act II. Up until that point, it appears that the protagonist of Fargo is Jerry Lundergaard, the hapless, bitterly frustrated car salesman who plots to have his wife kidnapped. That would, in fact, make Marge the antagonist, the Javert to Jerry’s Jean Valjean. But, as the narrative develops, we find that Fargo is balanced between Jerry, Marge and Carl Showalter, the fuming, delusional, small-time crook whom Jerry hires to kidnap his wife.

Good Riddance

This is the kind of man who makes me ashamed of being born in Illinois. During the Clinton impeachment his smug, overweening hypocrisy made me sick to my stomach on a daily basis.

The world is now a slightly better place.

Coen Bros: The Hudsucker Proxy

THE LITTLE GUY: No Coen Bros movie illustrates their interest in social mobility more graphically than The Hudsucker Proxy. Norville Barnes is a hick from Muncie, Indiana who rises up, up, up in the sophisticated New York corporate world, then falls down, down, down and then, miraculously (the word is not too strong) rises back up to the top.

“Up” and “Down” are not mere words in The Hudsucker Proxy — they are story elements,almost characters. The action takes place in New York City, certainly the most vertical place in America, and largely within the Hudsucker headquarters, a 45-story skyscraper (44, not counting the mezzanine). Great emphasis is placed on the verticality of the building and what it means to its inhabitants. Norville begins his work at Hudsucker in the basement mailroom, a seething, windowless dungeon filled with oppressed humanity, and ends his work at the top, where the offices are huge, unpopulated rooms with vast floor space and high windows. Waring Hudsucker (the outgoing president) starts out at the top, both metaphorically and physically, but finds the top wanting, and so jumps out the 44th-floor window (45th, not counting the mezzanine) and plunges to his death. But we see by the end of the movie that Waring Hudsucker has risen again, this time into Heaven, before descending, yet again, to help Norville out of his problem.

So “up” is good and “down” is bad. Everyone wants to be “up,” no one wants to be “down.” Except for the beatniks, of course, who live “downtown” and whose oddball coffee bar is located in a basement. That’s just like those beatniks, turning the status quo on its head and drinking carrot juice on New Year’s Eve. Buzz the Elevator Gnat gets a great thrill from taking people up to the top or sending them down to the bottom. Norville Barnes must take a dozen different rides in that elevator in his journey from the bottom to the top to the bottom and back up to the top.

“Up and down,” it seems, in the world of The Hudsucker Proxy, are heavily loaded terms, full of danger and stress and sorrow. Fortunately, there is a solution: a thing that goes round and round, specifically the hula hoop, the blockbuster idea that Norville carries around in his head and The Hudsucker Proxy‘s narrative secret weapon. His blueprint for the hoop, a simple circle drawn on a piece of scrap paper, baffles and confounds all the Hudsucker employees who behold it. No wonder: they live in New York City (the most grid-like major city on Earth), and work in a building that’s all about rising up and falling down. There’s nothing “round and round” about their lives, and Norville seems either quite stupid or stunningly insane to them for thinking of a circle (the hoop prototype is even made crimson red, to better set it off from all the squares and rectangles in the board room).

The hula hoop, like the baby in Raising Arizona, is nothing less than a holy ideal, one the “squares” (another beatnik term!) in Hudsucker Industries aren’t quite ready for. In a world of up and down, Norville thinks in terms of round and round, and that makes him inscrutable, unpredictable and dangerous. And so much of the dialog around Hudsucker Industries concerns things going up and down and round and round. The business stock falls, then rises, then falls again, then rises again, four different characters are compelled to jump out the 44th floor (45th, not counting the mezzanine), while divine, ineffable notions are expressed in terms like “the great wheel of life” or “what goes around comes around” or “the music plays and the wheel turns.”

What besides divinity could explain the actions of the lone hula hoop, the one that escapes its death in the alley of the toy store to roll purposefully out into the street, through the grid of the small town streets, to circle a child and land at his feet (upon the firmly-stated grid of the sidewalk)?

(A scientist shows up in a newsreel to tell us that the hula hoop operates on “the same principles that keep the earth spinning around and around,” and keep you from flying off into space — an instance of science vainly trying to explain the divine, as though there were a quantifiable “reason” why the Earth spins.)

(We know that the hula hoop is a divinely inspired creation because Waring Hudsucker’s halo, at the end of the movie, is also a hula hoop. He even makes a comment about how halos on angels won’t last, are simply “a fad.”)

(The hula hoop is not the only “holy spinning thing” that shows up in Coen Bros movies. There is also the hubcap/lampshade/flying-saucer in The Man Who Knew Too Much and the bowling balls in The Big Lebowski.)

In between the square and the round, quite literally, is the big clock at the top of the Hudsucker building. The clock symbolizes Time, which, it has been noted, moves on (“Tempus Fugit” is the slogan of the newsreel shown halfway through, Tidbits of Time). Yes, time does move on, as we are reminded whenever we see the enormous clock hand sweep through the office of Sidney J. Mussberger. The narrator (another Coen mainstay), Mose the Clockkeeper, does not identify himself as God but that’s the role he plays in Hudsucker. Time is money, says Mose, and money is what makes the world go around, and that, I suppose, is why the round clock is fixed in its square hole on the side of the rectangular Hudsucker building. Because Time may be round, and so is the world (at least the globe in Mussberger’s office is) but Money is square in both shape and temperament, and I guess that means Mose’s job is to square the circle and keep everything in balance, which I suppose is why the clock in The Hudsucker Proxy is so influential. When the Hudsucker clock stops, everything stops (except the snow, oddly).

(That clock wasn’t chosen at random — it bears a startling resemblance to the clock in Metropolis — another movie where down is bad and crowded, up is good and roomy, and a clock rules the world.)

(Waring Hudsucker, when he appears as an angel at the end of the movie, sings “She’ll Be Comin’ ‘Round the Mountain” as he descends from the heavens — a small point perhaps, but he’s not singing about going up a mountain or coming down a mountain, which one would think would be the natural order of things in songs about mountains.)

(Mussberger, it should be said, has his own influence over time — he makes his clacking pendulum balls [five round objects in a rectangular framework] stop on command, something Mose also accomplishes when he stops the world in Act III.)

Mose explains in the opening narration that everyone on New Year’s Eve wants to be able to grab hold of a moment and keep it, but only Norville manages to actually do such a thing, because he is, alone among characters in Hudsucker, divinely inspired. (Well, except for Buzz, who turns out, incongruously, to have his own round idea.)

IS NORVILLE A MORON? This is the question that haunts The Hudsucker Proxy and which, I submit, accounts for its lack of popularity. For the plot of Hudsucker to have maximum impact, the audience must believe, as Mussberger and streetwise reporter Amy Archer do, that Norville is a blithering idiot. Then, when it turns out he is divinely inspired, we are to look at Norville in a new light. The trouble is, the Coens have cast Tim Robbins, an actor who oozes intelligence, to play Norville. To compensate for his innate intelligence, Robbins plays the part as though wearing a neon “DOOFUS” sign on his head. When I read the script, the story of Norville amazed me and made me weep. I could see what the Coens (and Sam Raimi) were after — a comedy along the lines of Mr. Deeds Goes To Town or It’s a Wonderful Life, with a helping of His Girl Friday thrown in for good measure. Trouble is, Gary Cooper and James Stewart and Cary Grant are all long dead, and Tim Robbins, although an excellent actor, is not a Gary Cooper or a James Stewart or a Cary Grant. When I read the script I imagined Tom Hanks in the part of Norville (Hanks would, of course, catch up with the Coens in The Ladykillers) — I’m convinced the star of Big would have knocked Norville out of the park. The result of Robbins’s casting is that Norville’s actions are all in big quotation marks — we don’t see a simple guy trying to front, we see an intelligent actor trying to convince us he’s a country-born rube. The actor holds the character at arm’s length, showing him to us, commenting on him, not quite able to inhabit him.

(I should note that Robbins’s performance is a symptom of a larger problem in The Hudsucker Proxy — the Coens have lured a huge raft of talented actors and instructed them to act in the style of 30s screwball comedies — a task they all pull off with great skill [I am particularly astonished of Jennifer Jason Leigh’s jaw-dropping rendition of Rosalind Russell]. The trouble is that that style of acting was a natural outgrowth of its time, not an homage to an earlier style of acting. Watch The Lady Eve [which Hudsucker explicitly quotes a couple of times] back to back with The Hudsucker Proxy and you’ll see exactly what I mean.)

(And while I’m here, I should note that the Coens, in their script for Hudsucker, have crafted an incredible simulation of a Preston Sturges 30s screwball comedy, but then, oddly, have set the story in a Billy Wilder sort of world of 1950s business comedies. That right there, I think, accounts for people not quite being able to get a handle on Hudsucker, despite its towering achievements. And I do mean towering — this movie, with one of the greatest scripts I’ve ever read, is a bursting cornucopia of invention, wit and bravura moviemaking.)

(And while I’m at it, I should not that I am not immune from this temptation. I once wrote a romantic comedy with roles for Cary Grant and Katherine Hepburn. Imagine my chagrin when I learned they were, in a big way, not available.)

A SECOND CHANCE: Norville fails, and falls, but rises again. Waring Hudsucker falls and rises, then descends and rises again. Waring Hudsucker could not give himself a second chance, but he posthumously grants one to Norville. It seems everything in The Hudsucker Proxy happens more than once — Norville comes into Mussberger’s office to show him his idea, only to get fired and collapse on the floor. Later, Buzz comes into Norville’s office to show him his idea, only to get fired and collapse on the floor. The music plays and the wheel goes round, humanity keeps repeating the same scenes over and over. And this might be coincidence, if not for Norville discussing reincarnation with Amy — in a way, Norville is both a reincarnation of Waring Hudsucker and his second chance. He arrives at the building the instant Waring hits the street in front of it, is instantly made president, and is ultimately granted all of Hudsucker’s stock — precisely so that he need not make the same mistakes that Hudsucker did. Norville believes in reincarnation and roundness, while Mussberger can only think of up and down, squares and “when you’re dead, you stay dead.”

Failure, Waring Hudsucker notes, whether in business or in love, looks only to the past, and the future, as it says on his big clock, is now. This is The Hudsucker Proxy‘s notion of Zen — there is no future, it insists, there is only the moment, grabbing it, holding it, and living in it. Ironically, it was the Coen’s first real commercial disaster, showing them how the real world reacts to the real Norvilles who come along with their divinely inspired inventions.

(Full disclosure: this writer has a tiny role in The Hudsucker Proxy — I would call it a one-line role, but since they messed with my voice, I’m not even sure if I have the one line any more. It was a lot of fun shooting it and maybe I’ll write a piece about that some day. But not today.)

Coen Bros: Barton Fink

Barton and Charlie compare their soles.

THE LITTLE GUY: I don’t like to dwell on the symbolism of Opening Shots, but the first thing we see in Barton Fink is a lead weight descending on a rope, backstage in a Broadway theater. The weight comes down as the protagonist’s career goes up.

Barton Fink finds its protagonist at a moment of transition, socially speaking. He’s just become a success on Broadway and is quite pleased with himself, but is tempted by the opportunity to go to Hollywood and write for the movies. When he gets to Hollywood, he finds that no one knows who he is, no one has seen his play, no one cares about his ideas and he’s back at the bottom of the social order again.

(It was fantasies like Barton Fink that led me to believe that life could be good as a playwright in New York. Damn you, Barton Fink!)

Barton is solipsistic, egocentric, self-important, conceited, delusional, inward, dense and utterly humorless. He has a success on Broadway, a kitchen-sink drama about “real people,” cheered by swanky society types in white ties and ball gowns while Barton thinks he’s struck a blow for the “common man.” Meanwhile, he looks down on movies, is completely unfamiliar with the form in fact, as worthless garbage (this at the height of the studio system, the first “golden age” of Hollywood and the year of Citizen Kane). So he loves the “common man” and wants to create a “real theater” for them, while writing plays for the wealthy to coo over and disdaining popular culture.

(How self-involved is Barton? He’s so self-involved that the actor we hear reciting Barton’s lines onstage in the Broadway theater is the same actor who plays Barton, John Turturro. This play, this production, this theater, this success, it seems, is all in Barton’s head. The theater is all in Barton’s head, just as the Hotel Earle, we will find, is all in Charlie Meadows’s head.)

WHO IS BARTON FINK? Maybe Barton Fink is really just a movie about a delusional playwright who leaves New York, goes to Hollywood and gets into a mess of trouble. But I don’t think so. Symbols and indicators keep piling up and the narrative takes a sharp left turn at the end of Act II, turning Barton Fink from an off-center Hollywood comedy to something darker, creepier, harder to “get” and more cosmic. This is, in fact, the movie that, for me, moved the Coens from the “interesting filmmakers to watch” list to the “all-time great, long-term artist” list.

Barton isn’t just a playwright moving to Hollywood. He’s a “serious” playwright moving to Hollywood, a town that has a phobia of “serious,” a town which, since time immemorial, is where writers go to lose their souls. Moreover, he’s a serious playwright moving to Hollywood in late 1941, as World War II raged in Europe and American involvement was just about to begin. The signs of this are everywhere in Barton Fink, but Fink himself remains absolutely oblivious throughout. Even when he goes out to celebrate at a USO show, in a dance floor filled with uniforms, he utterly refuses to acknowledge who these soldiers and sailors are and what they’re about to go do (in Barton’s defense, the all-goyim army at the USO show recognize Barton as a bespectacled Jewish freak — and proceed to attack him).

So: Barton is a delusional, self-involved playwright lost in Hollywood, utterly oblivious to the world situation as he struggles to write a B-movie. And the movie hangs together as far as that goes, but then there is the question of Barton’s Jewishness. People bring it up all the time, and never in a favorable light. The Jews who run the studio call each other “kike” and constantly cut each other down, while the (German and Italian) detectives who come around in Act III are decidedly more ominous in their dealings with Fink. So, Barton, it seems, is a self-involved Jewish playwright who gets lost in Hollywood as World War II rages in The Old Country. (“Minsk, if you want to go all the way back,” offers studio-boss Lipnick, underlining the connection from Hollywood to New York to Eastern Europe.) He’s a Jew ignoring the Holocaust, writing self-important nonsense while his people are slaughtered by the millions. Even when Lipnick himself turns up in a colonel’s uniform and starts spouting patriotic rhetoric (“Don’t you know there’s a war on?!”), Barton remains firmly in his own head. He even stuffs his ears with cotton to drown out the sounds of the hotel as he writes his meaningless, pretentious, self-important screenplay, as blood dries on his bed’s mattress not three feet away.

If Barton is a self-involved Jew, the mosquito that keeps him up all night is that thing that would keep any Jew up all night in 1941, that niggling, inescapable sensation that something is coming for you, something that wants your blood. Perhaps it’s my imagination, but the mosquito’s buzzing seems to echo the tinny sound of a faraway air-raid siren.

Who gets Barton into this mess? His decidedly non-Jewish agent in New York, Garland Jeffries. And who does Barton aspire to be, who does he look up to? William P. Mayhew, respected Southern Novelist. And, it turns out, a complete fraud.

(Later, Barton will find himself, ironically, becoming more and more like Mayhew — a failed has-been who can’t get his scripts made, a fraud who gets his ideas from Mayhew’s muse, and an early-morning drinker.)

WHAT IS THIS HOTEL? Barton moves into this run-down hotel, the Earle. What is the Earle? There are strong indications that it’s not a “real” place. First of all, we never see anyone there besides Barton, the desk clerk and Charlie, Barton’s next-door neighbor. Secondly, Barton’s room hasn’t been touched in years — almost as though this room has been waiting here for him all his life, that he is the first and last guest ever to stay here.

Then there’s the wallpaper, which keeps falling off the walls, with icky, sticky gunk dripping from it. The same icky, sticky gunk is seen later dripping from the ears of Charlie, making a solid connection between the hotel and Charlie. Charlie mentions at one point that he can hear the couple on the other side of Barton making love, suggesting that he can, in fact, hear everything in the hotel. Later on, Charlie suggests that the hotel is, in fact, his home. All these things suggest that the hotel is a part of Charlie, that Barton, essentially, lives inside Charlie’s head.

(As the wallpaper peels off, the veneer of the mask of the hotel peels away too. It’s not for nothing that the wallpaper catches on fire as Charlie/Karl charges down the hall at the end of the movie.)

THEN WHO IS CHARLIE? Well, first off, we know by the end of the movie that Charlie isn’t Charlie, he’s Karl Mundt, a crazed killer who chops up bodies and keeps their heads. If the Earle is his home, his “head office” (a term Charlie uses in Act III: “I know what it’s like when things get balled up at the head office”), I’m going to go out on a symbolist limb here and say that Charlie is Satan and the Hotel Earle is Hell.

(“You come into my home and complain about about too much noise?” cries Charlie in disbelief, just before setting Barton free from the holocaust he’s created.)

(I might mention here that, just as Charlie is not really Charlie, Chet [the bellman] may not really be named Chet — we only have his word for that, and his business card is a blank rectangle with the word “Chet!” scrawled on it [rather like a movie screen, that blank white rectangle — another blank for projecting a fantasy].)

(The devil Charlie does not challenge his doomed to a chess match — no, he’s a regular-guy, blue-collar kind of devil — he invites Bart to a wrestling match. And soundly trounces him. To make the connection clearer for the audience, the Coens have Barton watch the dailies of a picture called Devil on the Canvas, featuring an enormous man repeatedly shouting “I will destroy him!”)

(It’s ironic that Barton first meets Charlie after he complains about Charlie making too much noise while sobbing next door — for a man who doesn’t listen, refusing to pay attention to suffering [while making it the subject of his writing, of course], he’s got a mighty sensitive ear.)

In Act III, a couple of detectives, Deutsch and Mastronetti, come looking for Mundt, and act extremely threateningly toward Barton. It cannot be a coincidence that the men looking for Satan in the Hotel Earle in 1941 are German and Italian, hate Jews, and end up being destroyed by the entity they seek, any more than it could be a coincidence that Charlie/Karl/Satan mockingly chirps “Heil Hitler” before blowing off the German’s head.

NOW THEN: If Miller’s Crossing is about hats, Barton Fink is about shoes. (And, conversely, heads.) I was watching Barton Fink a few times ago and thought “Barton is concerned about his soul, and there are all these prominent shots of shoes in the movie. Could the Coens be making a glib “soul-sole” connection? And yet, once I had made the connection myself, the whole movie fell into place. Barton moves into the Earle, which is Hell. The bellman, Chet, emerges up from a trap door in the floor, clutching a shoe, the sole toward the camera. Chet, it seems, is a demon in Charlie’s Hell whose job it is to collect souls. Later in the movie we see him moving his shoe cart down the empty hall, that empty hall of the hotel with no one in it, and yet there is a pair of shoes outside every door. The people are gone, the souls remain. At another point, Barton and Charlie get each other’s shoes (Barton finds Charlie’s too big for him). Still later, when studio-boss Lipnick wants to show his devotion to Barton’s purity, he kisses the sole of his shoe.

(Barton first discovers Charlie because he hears Charlie weeping next door, but by the end of the movie it is Barton we can hear weeping alone in his room from the empty, shoe-filled hallway.)

AND THEN THERE’S THE HEADS: The Broadway theater is all in Barton’s head, the hotel is all in Charlie/Karl’s head, Mayhew’s career is all in his head, his muse’s head is (supposedly) in a box on Barton’s nightstand, Charlie/Karl complains about things getting “balled up at the head office,” which is his code phrase for “I’m getting the overwhelming urge to kill again,” but when Mayhew’s muse’s body is discovered he insists “We have to keep our heads.” Lipnick tells Barton twice that his studio owns “Whatever rattles around that fat kike head of yours,” Charlie complains that his head is killing him, just after charging down the hallway screaming “I will show you the life of the mind!” and earlier comforts Barton by saying the extremely uncomforting homily “Where there’s a head, there’s hope.”

SO WHO’S THE GIRL? As Barton writes, a photo of a girl on a beach hangs over his desk. He often contemplates this picture, and then, magically, meets the same girl on the same beach at the end of the movie. Is the girl a siren, an unattainable mirage, there to tempt Barton ever onward onto the dangerous rocks of Hollywood? Why does he place Charlie/Karl’s picture next to hers for inspiration? Is it because, when he first heard Charlie laughing/crying in the next room, his voice seemed to come from the picture? Is the girl just another incarnation of the devil, tempting Barton toward his fate? When Barton meets her, she says “It’s a beautiful day” and Barton, typically, cannot hear her. When he asks if she’s in pictures, she says “Don’t be silly.” Barton, of course, is asking “Are you the same girl who’s in the picture over my desk?” but the girl responds as though he’s asking “Are you an actress?” By replying “Don’t be silly” is she saying that she’s not the girl in the picture, or is she saying that movies are, as Barton has suspected all along, silly? And what does it mean when Barton, while watching the dailies for Devil on the Canvas, hears the pounding sea on the soundtrack? And what does it mean when the shots from Devil on the Canvas are echoedin the USO fight? And why do the grunts and yells from Devil on the Canvas are echoed in the drainpipe the camera disappears down at the end of Act II? Do we hear the shouts from Devil on the Canvas because the pipes are within Charlie/Karl’s head, or because the pipes lead to the sea (classic symbol of chaos), where the girl sits on the beach?

ANOTHER VIEW ON BARTON’S DILEMMA: When Charlie/Karl pulls his shotgun out of his policy case, I am reminded of a lecture I once saw by David Mamet. He told the audience that the purpose of art is “not to instruct, but to delight.” An audience member raised their hand and said, in a very Barton Fink sort of way, “Yes, but doesn’t the artist have a duty to try to change the way people think?” To which Mamet said “If you want to change the way people think, art is not a very good tool for that. There is, however, an excellent tool for changing the way people think — it’s called a gun.”

ECHOES: Barton Fink, like many Coen movies, is about a non-talker lost in a sea of blabbermouths. Barton only talks when he’s feeling confident enough to do so (and then he’s a gibbering moron), but Charlie and Lipnick and Geisler are all motor-mouthed yappers.

Tony Shaloub plays Geisler, and the Coens, apparently, liked the scene in the studio commissary where Geisler counsels Barton while stuffing his face so much that they had him do the exact same scene again in The Man Who Wasn’t There.