DC vs DCU

Tonight’s bedtime conversation with Sam (5).

SAM. Is tomorrow a school day?

DAD. No. It’s Presidents’ Day. Do you know who the Presidents are?

SAM. Yes.

DAD. Yeah? Can you name one? Who was a President?

SAM. (patiently, as though to a dull toddler) George Washington.

DAD. Do you know what the President does?

This Sam is less clear on. Which is just as well at this embarrassing point in our nation’s history.

I start to say that if the United States is the DC Universe, you could look at George Washington as Superman, but then I realize that if I say that, the next question will be “Then who is Batman?” and I don’t have a clear answer for that.

Clearly, George Washington is Superman. He was the first, arguably the most important, debatably the best, and most importantly the “original.” But then, indeed, who is Batman? Is it Adams, contemporary of Washington and close second in defining the young nation’s ethos? Or is it, say, Lincoln, the most beloved of the presidents, the tall, dark, brooding loner president, the tortured insomniac, haunted by the deaths of his loved ones, the one who broke the rules for the sake of the greater good?

Does that make Wonder Woman Thomas Jefferson, the warrior for peace, architect of our most precious freedoms? Or is she more like Franklin Roosevelt in that regard, giving our enemies a bitter fight while generously giving our poorest and weakest a fighting chance of their own? That would make Truman Green Lantern, saving the world with his magical do-anything world-saving device.

And who would be an analog for colorless chair-warmers like Millard Fillmore and Chester Arthur? Are these men Booster Gold and Blue Beetle? Clearly Rorshach is Richard Nixon, Alan Moore practically begs us to see the parallels, but what of Kennedy, Nixon’s shining twin? Is that Ozymandius, or is he a simpler man, a purer spirit, someone like Captain Marvel? Or is he Superboy and his “best and brightest” cabinet the Legion of Superheroes in the 31st century?

And how to categorize corrupt, incompetent disasters like Grant, Harding, Hoover and Bush II? Is Reagan Plastic Man, effortlessly escaping ceaseless attack with a smile and a quip? And what about Johnson, weak on foreign policy but a genius in the domestic realm, who is that? Or William Henry Harrison, who caught pneumonia during his inaugural parade and died a month later? Or Grover Cleveland, who served, left office, then came back and served again?

Or perhaps the metaphor is imprecise, perhaps the US presidency is unlike the DCU after all — perhaps it’s more like the X-Men, where weak individuals are granted extraordinary powers and yet are still hampered by their combative attitudes toward each other and their under-developed social skills. In the X-Men you have heroes who might not turn out to be heroes after all. And vice versa.

Or maybe we’re looking in the wrong direction, perhaps the US presidents aren’t the “good guys” at all. While Bush II has so far shunned the metal mask and hooded cloak of Dr. Doom, he has certainly succeeded in turning the US into his own private Latveria. And any given Republican of the 20th century can lay claim to being the Lex Luthor of the bunch, brimming with brilliant, short-sighted schemes to make himself rich while destroying other people’s lives and property.

And, if they were given the choice, is there any serious doubt as to whether Americans would elect a comic-book character over a living, breathing human being?

My Supergirl

As a comics fan and the father of a young Supergirl-loving daughter, I have been following the recent controversy surrounding the recent appearance of Supergirl.

Recently, a meme has sprung up in response, wherein various artists have contributed their concepts toward a new vision of Kara, the last cousin of Krypton. Above is my effort.

I do not claim supremacy in the sequential arts.

You may click to see it larger.

UPDATE: Unable to leave poor enough alone, I have fiddled with the shading to make her a tad more realistically lit.

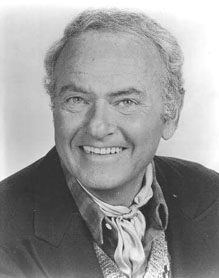

Oh, those paranoid delusions: Harvey, They Might Be Giants, Man of La Mancha

Three movies about men with delusions. In Harvey, James Stewart believes he’s followed around by a tall white rabbit, in They Might Be Giants George C. Scott believes he is Sherlock Holmes, in Man of La Mancha Peter O’Toole believes he’s a good actor Don Quixote.

In each of these movies, the families of the men seek to have them committed. In each of these movies, the filmmakers would like us to side with the crazy guy. Insanity is so cute in Hollywood. It’s not destructive or terrifying or heart-rending, it’s sweet and harmless and adorable, and if we look upon these men as anything other than inspirational, isn’t it really we who are the crazy ones?

Call me mean-spirited, but by the end of Harvey I wanted to strap James Stewart down to a table and give him electro-shock therapy. That would wipe that sweet, silly grin off his face. Stewart was nominated for an Oscar for this cloying, sentimental performance (big surprise) (and later repeated it for a 1972 TV version), but I’m glad I saw him first in Vertigo and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.

SPOILER ALERT: It turns out the rabbit is real.

They Might Be Giants is the most enjoyable, at least for the first half. George C. Scott actually makes a pretty good Holmes, acerbic, arrogant, full of himself, and the sight of him wandering around a gritty, 1970 New York is startling. The movie also gets points for inspiring the name of my favorite currently-working American band. It also gets points for featuring a fine New York cast, including Jack Gilford as a librarian, F. Murray Abraham as a theater usher, Eugene Roche as a policeman, M. Emmet Walsh as a garbageman and James Tolkan as some guy. Alas, the movie is about a crazy guy and the analyst trying to cure him, so by the mid-point of the movie the analyst starts believing in him, and so does everyone else he’s met, and the narrative quickly gets retarded real fast. By the final reel it spirals completely out of control; the analyst falls in love with her patient, the performances turn disastrously sentimental and the narrative even clumsily attempts to enter the cosmic.

Man of La Mancha is just awful, a stagebound chore of a movie. A film of a musical of a novel (that would be Don Quixote), it fails on all levels. Released in 1972, late in the Hollywood Musical run, it stages its numbers almost apologetically, as though embarrassed to include them at all. The actors shuffle around the soundstage, “talking” the lyrics and half-heartedly moving to the music without actually performing any choreography. Several conceptual devices, such as mixing locations with soundstages and filming fantasy with “gritty 70s realism” camera work gut whatever effect the stage musical was after. Peter O’Toole is okay in a stylized way as Don Quixote but his scenes as Cervantes are unwatchably, depressingly loud, hammy and emphatic in the “Great British Actor” mode (cf Richard Burton, Laurence Oliver).

What is it about clinical insanity that Hollywood feels such a need to defend? They want us to love these kooky misfits, they want us to hold them up for high regard, as they see the world more clearly than we do.

Can someone please direct me to a movie that portrays insanity as something other than a cute, harmless eccentricity? Certainly, somewhere in cinematic history, insanity has been portrayed somewhere between the two extremes of Arsenic and Old Lace and Psycho.

They Might Be Giants, in its own way, is also an adaptation of Don Quixote and takes it’s title from Quixote’s response to the windmills: yes, they look like windmills, but they might be giants. This makes it a perfect name for the band, and for a movie about a guy who thinks he’s Sherlock Holmes.

And how perfect is it that Pedro Almodovar (pictured above) is literally a Man of La Mancha?

All three of these movies were based on stage plays, and all of them show it to one degree or another. This is another good reason to abandon theater as an art form.

The Jaws of Love

(Another piece from my monologue days.)

I’m a man, I’m an idiot, it follows. I’m a man, I’m an idiot.

I’m human, that’s the problem. I’m human, I’m an idiot, it follows. I’m human, I’m an idiot. You can’t teach me anything, I won’t learn, I’ll never learn, I can’t learn, I’m an idiot, I’m trapped and you can’t teach me anything.

You ever look into someone’s eyes and been reduced to the size of a pin? A pin, a pinpoint of light, been reduced to a pinpoint of light? You ever see someone toss their hair back and it made you fall silent? You could be talking to someone — “Oh, yes, the third episode with the dwarf was the best” — and they do this –

[imitation of hair-flip]

— and you fall silent. Because, you know why? Because Something Important Has Happened. Or, or, you’re talking to this person, this person, this certain person who makes your heart want to get in your car and turn on some rockabilly and drive somewhere, and you’re hanging on every word this person says, and then this person says something like —

…”that would be nice”…

— and it dislodges this rock, somewhere in the deep stream of your subconscious this rock is dislodged, and you find yourself thinking about things you haven’t thought about in years. Am I ugly? Do I need some mints? How come I never read any Shelley? Jesus, do I weigh that much? This rock is dislodged, it sets off an avalanche in your head that wipes out everything else in your brain.

And you fall silent. It’s like you’re in church, it’s like you’re worshipping. Because you are in church. You are worshipping. You are having a religious experience.

Why? Why this person? Who is this person? What do you know about this person? Doesn’t this person have terrible taste in music? Doesn’t this person smoke? Isn’t this person ten years older than you? Isn’t this person not attracted to your sex? Doesn’t this person think you’re an insignificant blot on an otherwise charming landscape? Isn’t this person the rudest, clumsiest, most incorrigibly maddeningly frustratingly difficult person you’ve ever met in your life? Well? Then why? Why are you talking to this person? What is the point? Why are you bothering? Why do I find myself in this exact same position right now?!

Because —

[gesture to body]

— this, you see, this, you know what this is, this is flesh. It’s all I’ve got. It’s all they gave me. I didn’t get a book of rules. I didn’t get a wise old mind that could see into the future and tell me that these feelings would die, that lovemaking would become rote and tiresome, that I would lose interest, that we would get into fights over things like, like white-out!

I didn’t get that mind, my mind doesn’t say those things, my mind says things like YES! My mind says things like NOW! My mind says things like DANCE, like, like, KISS, like, like, GRAB THIS PERSON NOW! GRAB THIS PERSON NOW!

I don’t know what it is, of course I don’t know what it is. It’s not meant to be known, not by us, not by me, not in this life, not in this world. It’s a feeling, that’s all, it’s a feeling, you know it when you feel it, it’s like these jaws snapping shut on you, on me, like they’ve shut on me, and I’m trapped, because, because, I’m a man, I’m an idiot, it follows, like I said, these jaws are as big as the fucking universe, and they’ll chew me up and spit me out, and I’ll never learn, I’m trapped, I’m an idiot, and I’m trapped in the jaws of love.

Happy Almost Valentine’s Day

For your romantic inspiration, some tender moments from Justice League.

This is, of course, the real reason why I watch the shows of the DC Animated Universe — it’s all the hot, hot man/woman, woman/alien, man/mythological figure, man/scientific experiment, man/winged alien, woman/alien, psychopath/psychopath, woman/scientific experiment, alien/robot, martian/martian, man/psychopath, mythological figure/martian, alien/winged alien, woman/mythological figure love going on.

As my son Sam (5) exclaimed after one episode of Justice League: “Everybody on this show is in love! I thought this show was supposed to be serious!”

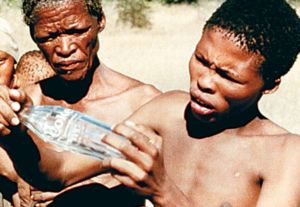

The Gods Must Be Crazy

It is not the goal of this journal to heap scorn, so I will keep this brief.

In the early 1980s, the movie The Gods Must Be Crazy was a surprise worldwide smash hit.

Why? Well, it has a delicious premise — a Coke bottle falls out of the sky (tossed from a passing airplane) and is found by a tribe of Bushmen in the Kalahari desert. The bottle, being unique and beautiful, leads to jealousy and conflicts in the tribe. So the leader of the tribe, Xi, decides to travel to “the end of the Earth” to return this gift to the Gods who, Xi believes, dropped it. As he travels to the end of the Earth, he encounters civilization, and civilization is shown to be ugly, cruel and insane compared to the simple, edenic life of Xi’s blessed, carefree people.

In addition to the premise, it showed, or claimed to show, the world something it had never seen or heard before — “real” Bushmen (that is, non-actors) and their click-consonant language.

People were amazed that, in the go-go 1980s, there were still “savages” living in total innocence, peaceful, child-like people whose world could be turned topsy-turvy by an object as innocuous as a Coke bottle. The movie’s fake National Geographic-documentary format helps reinforce this notion.

Wikipedia informs us:

“While a large Western white audience found the films funny, there was some considerable debate about its racial politics. The portrayal of Xi (particularly in the first film) as the naive innocent incapable of understanding the ways of the “gods” was viewed by some as patronising and insulting.”

Count me in!

Now, I’m a storyteller by trade, so I understand the comedic potential in viewing civilization through the eyes of a naif. It worked in Splash, it worked in Being There, it worked in Forrest Gump, it worked in Crocodile Dundee. But those movies weren’t pretending to show us “real” naifs; they employed professional actors to pretend to be innocent. The Gods Must Be Crazy got its international frisson by telling us that its protagonist was a real innocent, the comedic equivalent of a snuff film. “Watch as a genuine innocent gets humiliated and corrupted by the evil, evil West!”

What is “patronising and insulting” about the filmmaker’s treatment of the Bushmen in general and Xi in specific? The narrator tells us, many times, that conflict is unheard of in the Bushman world, that they don’t have words for “fight” or “punishment” or “war.” This may or may not be true; the writer (who is also the director, producer, cameraman and editor) presents it not for its factual basis but for its potential for comedic juxtaposition. The Bushmen were living in Eden and then this wicked, wicked Coke bottle fell out of the sky and brought conflict to them.

Now, I’m trying to think of something more insulting, more patronising one could say about a people than that they have no conflict, and no notion of conflict in their lives, and it’s not coming to me. To call such people “childlike” is an insult to children, whose lives positively boil over with conflict. To call such people more “natural” is an insult to Nature, which is defined as remorseless, brutal and ceaselessly ridden with conflict.

The DVD of this movie comes with a 2003 documentary, wherin a vidographer travels to Africa to find the tribe of N!xau (the actor, or non-actor, playing Xi) to find out for himself how much of The Gods Must Be Crazy‘s presentation of the Bushmen’s world is accurate. I could have saved him the time, because the falsehood of the movie’s premise is right there on the screen; the Bushmen of the movie are flabbergasted by the sight of a Coke bottle, but not of a film crew, recording their fictional actions. This is the height of insult in this loathsome movie — the filmmaker goes to the Kalahari, explains to the tribespeople who he is and what he’s trying to accomplish, puts the “genuine” tribespeople in costumes (or lack of them), constructs a fictional world they live in, asks them to perform comedic pantomimes illustrating a dramatic situation (“now, pretend you’ve never seen a Coke bottle before — it’ll be comedy gold!”), gets convincing, “authentic” performances from them, records it all on film, then assembles the finished movie to convince people that they are watching genuine innocents cavorting in an unspoiled Eden. And the white people of the Western world eat it up.

The insult to Xi and his people is compounded as Xi gains his education in civilization. He is put through hell in the form of the local justice system, with arrest, convicition and imprisonment for a crime he does not understand, and yet he remains, of course, thoroughly innocent, bewildered by what is happening to him. So apparently he is not only innocent, he is stupid and unconcerned for his own welfare. Not only that, he goes through his entire ordeal and apparently never sees another Coke bottle, or anything resembling such, never puts together that the magical, evil item that has beset his existence is, in fact, a common item of little consequence. That would make him a very stupid innocent indeed, but that is how the filmmaker presents him.

None of this would matter if the movie happened to also be a comedic gem, but it is not. It has a terrible script, wherin Xi’s quest to venture to the end of the earth is quickly shunted aside for unrelated storylines concerning a bumbling terrorist group and a bumbling researcher’s attempts to woo a pretty young schoolteacher. Sooner or later, all the storylines meet up, and wouldn’t you know it, Xi’s naivety and savage ways come in useful for the white people in the attainment their goals. In true western film tradition, and just so you know where the filmmaker’s heart truly lies, the white couple end up with most of the screen time and are given top billing.

The comedy is exceptionally broad and grating, and most of it operates at the level of an episode of Benny Hill, complete with copius undercranking and music-hall piano.

The technical aspects are abysmal; the image is washed-out, grainy and flat, and most of the sound seems to have been dubbed, badly, by amateurs.

The Evil Tub of Goo

The man who started it all.

In the spring of 1940, an unidentified criminal fell into a tub of goo. From this tub of goo emerged The Joker, and the world has never been the same. Clayface, Mr. Freeze, Two-Face, Solomon Grundy, Parasite, all fell victim, in one way or another, to tubs of goo. Christ, the Creeper fell into the same tub of goo as the Joker! You would have thought that having one person turn into a raving psycho would be enough for that company to stop manufacturing that particular brand of goo, but that’s corporate America for you.

(In the film Batman and Robin, even Poison Ivy falls into a tub of goo, although her comic-book counterpart did not seem to need to take it that far.)

Where would we be without tubs of goo? How many of our psychotics, mutants and monsters owe their existence to tubs of goo?

And not just villains, good guys too. Flash fell into a tub of goo too, and was struck by lightning to seal the deal. Metamorpho, Plastic Man, Swamp Thing — all goo-produced phenomena.

Over in the Marvel universe, in addition to having their own swamp thing called Man-Thing (who fell into the same tub of goo as Solomon Grundy but with vastly different effect) they actually have a tub of goo from outer space, one that will actively seek out people and jump on them, turning super-heroes bad and bad guys evil.

(It should be noted that the Marvel Universe seems to be plagued with radiation instead of tubs of goo, perhaps as a symptom of coming of age after the H-bomb testing began.)

Where is the anti tub-of-goo legislation? Or just lids, what about lids? Just put some goddamn lids on the tubs of goo, would that be so hard? Bruce Wayne needn’t have changed his life and become a fearsome creature of the night, he could have just sprung for some lids and his city would have been perfectly safe.

Road Warriors: It Happened One Night vs. The Sure Thing

Fifty years apart, two American movies, two sterling examples of the screenwriter’s craft, two young couples who hate each other, forced together on an adventure across the heartland, on their way to separate destinies, finding each other.

It Happened One Night was directed by Frank Capra, who had directed 24 other movies before this one, all of which have been forgotten, but who would go on to become one of the most beloved and iconic of American directors of all time.

The Sure Thing was directed by Rob Reiner, who had starred on a situation comedy and directed one previous feature, the classic This is Spinal Tap.

WHO IS THE GUY? In Night, it’s Clark Gable, cocky, charming newspaper reporter. In Thing, it’s John Cusack, cocky, witty college student.

WHO IS THE GIRL? In Night, it’s Claudette Colbert, spoiled heiress on the run from her stifling dad. In Thing, it’s Daphne Zuniga, stiff upper-class college girl with her life all planned out.

WHY ARE THEY FORCED TOGETHER? Night: Claudette is taking the low road to New York to see her husband, and Clark just lost his job and, for some reason, is on the same bus. Thing: Daphne is traveling to LA for Christmas break to see her law-student boyfriend, John is traveling to LA to get hooked up with the “sure thing” of the title.

WHAT DOES SHE WANT? Claudette wants to be free of her father’s yoke, Daphne wants order, calm and certainty — a commitment.

WHAT DOES HE WANT? Clark wants a story so good that it’ll show those bastards back in New York, John wants sex without responsibility.

MODES OF TRANSPORTATION: Clark and Claudette travel by bus, car, and hitchhiking. So do John and Daphne, although not in that order.

NOVELTY SONGS? You bet. Clark and Claudette bond over a busload of passengers singing “The Man on the Flying Trapeze,” while, conversely, John and Daphne silently pout during a torrent of showtunes belted out by their cute-as-buttons carmates (including a young Tim Robbins).

CRUMMY MOTELS? Yes and yes. And arguments over sleeping arrangements, a big deal in 1934, much more ambiguous and amorphous in 1985.

DANGEROUS MEN? In Night, Claudette is menaced by two guys, “Mr. Shapely,” a snide, chatty salesman, and Alan Hale, a jolly traveler who turns out to be a thief. In Thing, Daphne is menaced by a guy in a cowboy hat and pickup truck. In both movies, the guy rescues the girl by pretending to be a dangerous killer, scaring the guy off. For bonus points, in Night Clark Gable goes so far as to beat up Alan Hale, tie him to a tree and steal his car in order to protect Claudette’s honor (or at least her belongings).

BONDING OVER UNUSUAL FOOD? Yes and yes. Claudette has never eaten raw carrots, which Clark swipes from a farmer’s field, while John educates Daphne about cheese-balls, pork rinds and shotgunned cans of beer.

THE ELEMENTS: Clark and Claudette have to spend the night in a hayfield. John and Daphne temporarily get stuck in a rainstorm.

PRETENSE FOR ACCOMODATIONS? In Night, they pretend to be married to get a motel room. In Thing they pretend to be pregnant to get a ride.

T-SHIRT OR NO T-SHIRT? In Night, Clark Gable took off his shirt, revealing that he had no t-shirt on underneath, and all across the US t-shirt sales plummeted. In Thing, John Cusack wears a succession of nutty 80s novelty t-shirts to emphasize his quirky individuality. No report on the effect this had on nutty 80s t-shirts.

COSMIC MOMENT OF BONDING: Clark talks about an island he once visited in the Pacific and how he wants to marry a woman who would run in the surf with him on a night when “you, the stars and the water all become one,” while John talks about a camping trip he went on when he was a kid, where he looked up at the stars and wondered if there was an alien kid on one of those stars, also on a camping trip, looking up and wondering his own self.

A MAN HAS DREAMS: Clark dreams of telling off his editor while John dreams about a young lady in a white bikini. Plus ca change.

WHAT’S THAT STORY AGAIN? Both plots hinge to a certain extent on a story that the guy writes. In Night, Clark is writing the story of how Claudette disobeyed her father and ran away to be with her husband (of whom her father does not approve), but when he falls in love with Claudette his story goes right out the window. John is failing English and when his “sure thing” plans don’t pan out as expected, the story he writes both saves his grade and brings him his true desire.

WHAT DO THEY GET? Clark discovers that he doesn’t want that story after all, he wants to marry this dizzy princess. Claudette discovers that she doesn’t want to disobey her father after all, she wants to marry this cocky, disrespectful bastard. John discovers that the sex he craves so badly is meaningless without a commitment. Daphne discovers that commitment is meaningless if there is no life within it.

HOW DID THEY DO? Night was an enormous hit that made Capra a major director and swept the Oscars in 1934. Thing was a respectable success that won nothing.

SO WHO WINS? I have the utmost respect and admiration for It Happened One Night, but my heart belongs to The Sure Thing.

It’s hard to remember now that The Sure Thing was, at the time of its release, marketed as just another raunchy teen comedy of the sort launched by Porky’s in 1982. The script raises it far above the level of those other movies and the acting is simply extraordinary. John Cusack, actually looking the 18 he’s playing, gives a lovely, confident, multi-layered performance full of wit, irony and genuine comedic skill. Years before he played the “Woody Allen character” in Bullets Over Broadway, he can already be seen here channeling the Woodman with his timing, self-effacement and offhand charm. And Daphne Zuniga is lovely, real and utterly heartbreaking in her part, especially in her Act III scenes with her law-student boyfriend, where we see how far she’s come on her cross-country trip with John.

The climactic scene, where English teacher Viveca Lindfors reads Cusack’s story aloud to the class, is one of the loveliest I’ve ever encountered in a mainstream American film and a peak I have tried many times to match in my career, with little success.

Green Eggs and Ham

The inciting incident.

The unnamed protagonist of Dr. Seuss’s illustrated story Green Eggs and Ham wants only to be left alone — to sit in his chair and read his newspaper. He is content, his world is whole and complete. He is comfortable and complacent in his McLuhanesque media circuit. The only thing missing from his life is a name — an identity.

In the past, people like this have brought religion, political change or military turmoil to others. Sam brings green eggs and ham.

(It is, perhaps, significant that the protagonist reads a newspaper — movable type being, after all, the most important, world-shaking innovation in the history of the human pageant.)

Sam has more than an identity — he has mobility and, as we shall see, boundless resources at his disposal. Maybe he’s a shaman, maybe he’s a leader, maybe he’s a snake-oil peddler. Maybe he’s the marketing executive in charge of the Green Eggs and Ham account and this is a viral campaign. We are never told, and we must sort out the dense symbolism ourselves. Is Sam a savior or a demon? Seuss provides no easy answers.

The protagonist knows one thing: he does not like green eggs and ham. This is the same sort of person who knows they do not like democracy, psychoanalysis, astronomy, penicillin, abolition or stem-cell research (or, if you like, political torture, monopoly, pantheism). And yet, Sam will not stop pestering him. If the unnamed (not to be confused with Beckett’s Unnamable) protagonist will not take Sam’s new food straight, perhaps, Sam reasons, he will take it in a more complex form. In short order, Sam offers the protagonist his life-changing meat and eggs in a house, with a mouse, in a box, with a fox, in a car, a train, a boat, with a goat, on and on. And still the man with no identity resists. He spends the entire story trying to avoid change, even as change surrounds and engulfs him. Eyes closed, head haught, he repeatedly waves away Sam and his unusual food. He doesn’t even seem to realize that his life is continuously in danger as he stands on the hood of a moving car, then atop a moving train as it hurtles through a tunnel.

What can change this man’s mind? Nothing less than a cataclysm — car, train, boat, mouse, goat — all must plunge into the ocean. Finally, with death at his chin, the unnamed man relinquishes hiscontrol over his world (it’s a shame George W. Bush was not reading this instead of My Pet Goat on 9/11).

(What drives Sam? A hatred of the status quo? A religious conviction? Do-goodism? Or a simple desire to impose his will upon others? What does it mean that he wants to get the protagonist’s head out of the newspaper, remove his thoughts from the machinations of the world at large, to concentrate on the fleeting, earthly pleasures of the gourmand? Is he Satan? Is he the serpent, offering the protagonist the eggs-and-ham of carnal knowledge? Do the ham and eggs symbolize the penis and testicles? Is this perhaps a homosexual overture?)

Finally the protagonist submits and eats the food. And finds he likes it.

Of course, the story does not end there. In a shocking denoument, the man, still unnamed, typically, goes overboard. He has no greater a sense of himself than he did at the beginning. The man who knew only that he did not like green eggs and ham now knows only that he does. And, just as he was adamant about not eating it before, he is now adamant about eating it now. He crows to the skies regarding his plans to eat green eggs and ham in every possible situation, whether it is called for or not. For example it is not necessary to eat green eggs and ham in a box — in one’s kitchen, in the morning, would seemingly do just fine. Why insist on eating green eggs and ham with a goat? (Seuss draws the line at animals who would probably be interested in eating green eggs and ham, but it’s not hard to imagine that, before long, the unnamed protagonist will be forcing this food on chickens and pigs, unaware of his callous disregard for life.) So while Sam is triumphant in his quest to spread the gospel of green eggs and ham, what Seuss is really getting at is the unchanging simple-mindedness of the masses. “Thank you, thank you, Sam-I-am” intones the protagonist with the attitude of an “amen,” utterly forgetting that, just one madcap romp earlier, he hated this tiny, furry man and his plate of food. The man with no identity still has no identity — he’s just as happy being a green-eggs-and-ham eater as he was being a non-green-eggs-and-ham-eater. This is the knot of the problem Seuss, the master moralist and social critic, presents to us: things may change, but the masses, on a deeper level, do not change. Today it will be green eggs and ham, tomorrow it will be television or hula hoops or iPods, whatever shiny new thing the persuasive new voice brings. The day after it will be Nazism.

UPDATE: It occurs to me that the name “Sam-I-Am” is almost a homonym for “I am that I am,” the name the Old Testament God gave to Moses. Perhaps Sam-I-Am is God and the “Green Eggs and Ham” represent the new covenant with mankind, a different kind of trinity. This would, perhaps, make the unnamed protagonist Saul who became Paul and the train track the Road to Damascus.

The Princess Bride

Young’ns will hardly believe it, but 20 years ago Rob Reiner was once one of the most interesting and vital directors of commercial cinema in the US.

Check out this string of hits: This is Spinal Tap, The Sure Thing, Stand By Me, The Princess Bride, When Harry Met Sally, Misery, A Few Good Men, each one unusual for its time, innovative in some unexpected way, smart, and unerringly commercial. Usually if a director has three hits in a row he would be considered a master; this run is impressive by any definition.

The Princess Bride sits smack in the middle of this run and simultaneously the most old-fashioned and post-modern of these movies. The script, by “Nobody Knows Anything” William Goldman, manages to be both a loving send-up of old-fashioned adventure tales and a straight-ahead telling of those conventions at the same time.

A grandfather reads to a sick boy a book his father once read to him. The book is called The Princess Bride and the boy isn’t sure if he’s interested — it sounds like it’s for girls. And in the audience we’re not sure if we want to hear the story either — it sounds quaint, old-fashioned and soft. And in 1987, in the time of The Terminator at the box office, it was hardly the kind of story designed to sell mass quantities of tickets.

The story gets started and, indeed, it seems like it’s a girl story, a gothic tale of princes and princesses, trusty stablehands, pirates, giants and so forth. There is an over-the-top “kidding” aspect to the story and performances (which are scary good, Robin Wright and Cary Elwes being particularly perfect playing the delicate balance of camp and straight). But then something happens. In spite of the kidding nature, in spite of how silly the story is, in spite of the plot machinations being laid bare and discussed, the narrative takes hold. What the writer and director do is tell you “I’m going to tell you a story, it’ll be great, here’s how it will work, this is what you’ll think of this guy, this is what you’ll think of that guy, here’s how you’ll feel by the end,” and the jaded, seen-it-all viewer lets one’s guard down because one thinks that one is, like the kid, above the material. Then, amazingly, it turns out one is not above the material, in fact one can barely keep track of the plot as it changes direction so quickly. And it’s all stuff you’ve seen before but somehow you’ve never seen it quite this way before and before long, like the kid in the movie, one finds oneself completely wrapped up in a story that simultaneously feels ridiculously absurd and vitally true.

It’s like a magician who comes out and says “I’m going to do a trick for you, but first I want to show you how the trick is built, and how it works, and how it fools the audience, and how it’s going to fool you too,” and then goes ahead and performs the trick and it does fool you, even though you know how it works.

It works because, as storytellers have known for millenia, there are a number of fundamental principles that apply to good stories no matter what the genre, the format or the age of the audience. Master those principles and you can tell a story and take it apart at the same time, you can even chide the audience for getting involved in the story, the audience will still feel the same thrills and emotions.

The characters in The Princess Bride know this, certainly, that’s why they all have stories at the ready with which to justify themselves and deceive others. Westley has a story to convince people he’s a fearsome pirate, Vizzini has a story he’s beentelling himself for years about how a brilliant arch-criminal he is, Fezzig had a story he used to get the job working for Vizzini, Inigo has a story he’s been telling himself for years about the death of his father. Story has a vital and central place in the lives of these adventure-tale characters, and the filmmakers show that it has a vital and central place in our own lives as well.

Try this exercise at home: read Robert McKee’s Story, then watch The Princess Bride. For the young storyteller, few experiences will be more eye-opening and rewarding.