Thanksgiving greetings from What Does The Protagonist Want

For your holiday family viewing pleasure, I recommend taking your siblings and parents to Margot at the Wedding. It is neither heartwarming nor life-affirming, but I will promise you this: no matter who you are or what your family is like, there is not a chance in hell that they are as screwed up as the family in Margot at the Wedding. Seriously, you could have a sibling who, I don’t know, tortures animals for a living or something, and if you took that sibling to see Margot at the Wedding, I guarantee you, after the movie you will turn to that sibling and hug him or her and say “Thank you for being such a wonderful sibling.”

(Margot at the Wedding is a great family movie in the same way Your Friends and Neighbors is a great date movie. Anyone in any stage of any relationship could go see Your Friends and Neighbors and walk out feeling like they were with the warmest, kindest, most understand person on Earth. You could be dating a serial killer, and go to see Your Friends and Neighbors, and want to cuddle up nice and snuggly next to them afterward.)

So, Margot at the Wedding is about a really, seriously crazy woman who shows up to ruin her sister’s wedding. And that sounds like a facile movie cliche, but let’s not forget, Margot at the Wedding is written and directed by Noah Baumbach, who wrote and directed the shining miracle The Squid and the Whale, one of the greatest movies of this young century. Margot, in some ways, is almost a sequel to Squid, it’s like we follow that neurotic teenage boy and his even-more-neurotic middle-aged mom on an adventure in the country.And it’s one thing to say “crazy woman at the wedding,” but nothing I could say could prepare you for how sharply, finely-drawn this character is in her craziness. I’m assuming that she’s based on Noah Baumbach’s mother, and I’m kind of sorry that he had to live through that, but I’m glad he did and I didn’t, and I’m extra-glad that he at least inherited her talent for turning family trauma into great writing (if you see the movie this will all make sense).

The acting is wonderful throughout, but I just want to say, that Nicole Kidman? Boy she sure can act.

On a completely unrelated topic, I also watched Knocked Up this evening. I had missed it in the theaters for reasons having nothing to do with its qualities, which are supreme and abundant. I laughed, I cried, I recognized humanity.

Nicest of all, I got to watch both of these movies, for free, in the comfort and privacy of my own home. Why? Because I’m a member of the WGA, that’s why, and the studios send me all kinds of stuff to watch in the hopes I’ll vote for them for a writing award. That’s right, the studios care that I might like the writing in their movies, so they send me free DVDs.

And that’s why the WGA has to win this strike, because if the studios breaks the union I won’t get any more free DVDs between Halloween and Christmas.

Michael Clayton

As the applause died down and the credits rolled on the showing of Michael Clayton I attended tonight, I remembered that at Rotten Tomatoes the movie is currently enjoying a 90% percent “fresh” rating. For folks like me who think too much about these things, that number, 90, stuck out weird. It’s just too close to 100. 85, I know that’s going to be a pretty good movie, since a movie with an 85 obviously doesn’t appeal to absolutely everyone. But 90? That means that almost everyone liked it, except one or two people who didn’t. And after watching the movie (I intentionally did not read any of the reviews beforehand, as I didn’t want to know anything about it) I just had to find out who watched this movie, in a marketplace otherwise utterly devoid of intelligent, well-crafted, well-executed, adult entertainment, and said “feh.”

Rotten Tomatoes found two in their “Cream of the Crop” section — Jan Stuart seems to have been legitimately (slightly) disappointed, but the other negative review is by Rex Reed, who seems to be a total fucking moron.

He says that Gilroy’s writing and direction is illogical and incoherent, and then goes on at length about a minor story point that he, personally, knows to be at odds with how he and his friends experience the real world. Then he describes the plot of a movie that sounds similar to Michael Clayton, but is, in fact, not. Reed declares a total lack of understanding regarding a plot point that is given about twenty minutes of careful, step-by-step setup and development. Reading the text more closely, the only conclusion I could come to is that Reed did not actually finish watching the movie — rather, he checked out, or stormed out in a huff (as I have heard reports of him doing before) and then wrote his review based on his little brain’s offended imagination.

As a capper, Reed runs down Clayton as being of a piece with other “George Clooney movies:” Syriana is “loathsome,” Solaris is “unsalvageable” and O Brother, Where Art Thou? is “idiotic.” Why this man is even allowed inside a movie theater is a great mystery to me.

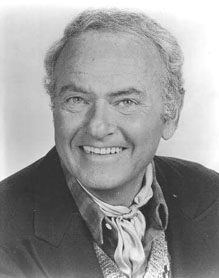

I enjoyed the movie a lot and so did my wife, but there was one tonal note that she found lacking: the portrayal of manic depression in the character of Arthur (Tom Wilkinson, pictured above) who goes off his meds (also pictured above) and provides the movie’s inciting incident. Arthur’s rants sounded right to me (in my relatively slight experience with bipolar folk) and my wife admits that, textually, they’re correct, and even admits that Wilkinson’s performance is exemplary, but that the rhythm of speech of the manic person is a very specific, un-wavering, unforgettable thing and that the central event of the movie was tarnished slightly by what she saw as a better-done-than-usual, but-not-perfect representation of bipolar disorder. (She knows a lot about this stuff. No, she is not, herself, bipolar.) Because I have an ongoing interest in representations of mental disorders in movies, I would like to throw this discussion open: any reader with experience with bipolar sufferers have an opinion on Arthur in Michael Clayton? And, extending from that, has anybody seen an accurate representation of bipolar disorder in a movie?

(One bipolar friend of mine was livid at As Good As It Gets, a movie that, in her eyes, had the message of “Love Will Allow You To Stop Taking Your Meds,” which she found to be inaccurate at best and grossly irresponsible at worst.)

Oh, those paranoid delusions: Harvey, They Might Be Giants, Man of La Mancha

Three movies about men with delusions. In Harvey, James Stewart believes he’s followed around by a tall white rabbit, in They Might Be Giants George C. Scott believes he is Sherlock Holmes, in Man of La Mancha Peter O’Toole believes he’s a good actor Don Quixote.

In each of these movies, the families of the men seek to have them committed. In each of these movies, the filmmakers would like us to side with the crazy guy. Insanity is so cute in Hollywood. It’s not destructive or terrifying or heart-rending, it’s sweet and harmless and adorable, and if we look upon these men as anything other than inspirational, isn’t it really we who are the crazy ones?

Call me mean-spirited, but by the end of Harvey I wanted to strap James Stewart down to a table and give him electro-shock therapy. That would wipe that sweet, silly grin off his face. Stewart was nominated for an Oscar for this cloying, sentimental performance (big surprise) (and later repeated it for a 1972 TV version), but I’m glad I saw him first in Vertigo and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.

SPOILER ALERT: It turns out the rabbit is real.

They Might Be Giants is the most enjoyable, at least for the first half. George C. Scott actually makes a pretty good Holmes, acerbic, arrogant, full of himself, and the sight of him wandering around a gritty, 1970 New York is startling. The movie also gets points for inspiring the name of my favorite currently-working American band. It also gets points for featuring a fine New York cast, including Jack Gilford as a librarian, F. Murray Abraham as a theater usher, Eugene Roche as a policeman, M. Emmet Walsh as a garbageman and James Tolkan as some guy. Alas, the movie is about a crazy guy and the analyst trying to cure him, so by the mid-point of the movie the analyst starts believing in him, and so does everyone else he’s met, and the narrative quickly gets retarded real fast. By the final reel it spirals completely out of control; the analyst falls in love with her patient, the performances turn disastrously sentimental and the narrative even clumsily attempts to enter the cosmic.

Man of La Mancha is just awful, a stagebound chore of a movie. A film of a musical of a novel (that would be Don Quixote), it fails on all levels. Released in 1972, late in the Hollywood Musical run, it stages its numbers almost apologetically, as though embarrassed to include them at all. The actors shuffle around the soundstage, “talking” the lyrics and half-heartedly moving to the music without actually performing any choreography. Several conceptual devices, such as mixing locations with soundstages and filming fantasy with “gritty 70s realism” camera work gut whatever effect the stage musical was after. Peter O’Toole is okay in a stylized way as Don Quixote but his scenes as Cervantes are unwatchably, depressingly loud, hammy and emphatic in the “Great British Actor” mode (cf Richard Burton, Laurence Oliver).

What is it about clinical insanity that Hollywood feels such a need to defend? They want us to love these kooky misfits, they want us to hold them up for high regard, as they see the world more clearly than we do.

Can someone please direct me to a movie that portrays insanity as something other than a cute, harmless eccentricity? Certainly, somewhere in cinematic history, insanity has been portrayed somewhere between the two extremes of Arsenic and Old Lace and Psycho.

They Might Be Giants, in its own way, is also an adaptation of Don Quixote and takes it’s title from Quixote’s response to the windmills: yes, they look like windmills, but they might be giants. This makes it a perfect name for the band, and for a movie about a guy who thinks he’s Sherlock Holmes.

And how perfect is it that Pedro Almodovar (pictured above) is literally a Man of La Mancha?

All three of these movies were based on stage plays, and all of them show it to one degree or another. This is another good reason to abandon theater as an art form.