The Happy Ending Shakespeare Company, Volume 2

KING LEAR

by William Shakespeare

(The throne room. LEAR and his daughter CORDELIA.)

LEAR. Do you love me, Cordelia?

CORDELIA. Of course I do father, don’t be silly.

LEAR. I just wanted to hear you say it.

(They embrace.)

The casting process, according to Mulholland Drive

The tiny man, Richard Nixon, the film composer, the cowboy. These men run Hollywood. In your dreams.

A pair of Italian brothers are financing a motion picture. It appears to be the story of a fictional or semi-fictional girl singer from the early sixties.

These Italians are tough customers. They know what they want, and they have extremely high standards for their espresso.

How do we know they’re tough? Because one of them is Richard Nixon (not to mention a Texas bar-owner) and the other is — I can barely even say it — a film composer.

Whatever you do, don’t mess with a film composer.

The tough Italians want an actress named Camilla Rhodes to play the girl singer. They are adamant about this. They are so adamant about it they can barely speak. They tremble with fury at the thought of anyone opposing them.

The director of the picture, a young man named Adam, doesn’t yet know who he wants for the part, but he knows he wants a say in the matter.

The studio is willing to put on a show of compromise for the director, but ultimately the decision has already been made — by a tiny man who lives in a windowless dark room. No one may touch the tiny man, who doesn’t even have a desk or a television, only a telephone and a glass wall with an intercom that faces a pair of double doors.

The tiny man seems to be the studio head, and he seems to be sympathetic to the Italians’ choice of girl.

It seems to be a bleak existence for the tiny man, but he appears to be content. He has, it seems, immense power and the few people who speak to him do so in stammering, gasping tones.

The director balks at the Italians’ behavior. No one’s going to tell him who to cast in his picture. He walks out of the meeting and trashes the Italians’ limo. I guess no one told him — the Italians are Richard Nixon and a film composer.

It’s nice to think that, in the world of David Lynch, a film composer outranks Richard Nixon.

The director soon feels the wrath of the Italians. They freeze his bank account while the tiny man in the dark room shuts down production on his movie. They strongly urge him to go see a cowboy who lives at the top of the Santa Monica mountains. The director (who has problems of his own) goes to see the cowboy who dishes out folk wisdom with an eerily calm demeanor and obliquely threatens the director’s life. The Italians, it seems, don’t know any Italian hit men — they must rely on eerily calm cowboys to do their dirty work.*

The director, humbled, awed by the displays of power from the Italians and the tiny man, goes to the next day’s casting session. Casting sessions in Hollywood, it seems, are expensive propositions. Sets are built and actors are put into full makeup and wardrobe. (Across town, a young actress, freshly in town, goes to try out for a picture and finds herself in the room with the lead actor, who apparently has made it his priority to attend every audition.) The Italians’ choice auditions and the director wisely points to her and says “This is the girl.”

And young actors ask me every day how to get an agent. If they were to only watch Mulholland Drive, they would know that agents have nothing to do with it. You are either chosen in advance by Italians working in concert with a tiny man in a windowless room, or else you walk in the door and get an audition with the star.

Of course, in the latter case, the elder, visiting casting director indicates that the producer (Alcott faveJames Karen) is going about his production all wrong. “He’ll never get this picture made,” she sighs. It makes perfect sense — he hasn’t made the proper arrangements with the Italians and the tiny man. It’s like they always say — it’s who you know.

Who the burnt guy is who lives behind the diner and owns a small blue box I have no idea.

*Wait a minute — they know some Italian hit-men after all. They send one mountainous one to the director’s house. He is unable to find the director, but he punches the director’s wife and her lover unconscious anyway.

The Happy Ending Shakespeare Company, Volume 1

The Happy Ending Shakespeare Company presents:

ROMEO AND JULIET

by William Shakespeare

(A street in Verona. ROMEO sits, looking sad. MERCUTIO enters.)

MERCUTIO. Romeo! What’s the matter?

ROMEO. I’m miserable because Rosaline dumped me.

MERCUTIO. Why don’t you go fuck a prostitute?

ROMEO. (immediately brightens) Hey! Great idea!

The Man Who Fell to Earth

Thomas Jerome Newton is from another planet. In a piece of canny 1970s casting, he is played by David Bowie.

Newton has come to Earth with a number of extremely valuable patents tucked under his arm. His plan is: find the world’s greatest patent attorney, form a gigantic corporation that will generate hundreds of millions of dollars of income, and use the money to — to — well, that’s the part where I get lost.

Apparently his planet is in trouble. They’re all out of water, and they desperately need water to — to — well I’m sure they need it to live, but all we ever see in the movie is that they use copious amounts of it in the course of their marital duties. But that’s enough, fine. Thomas Jerome Newton needs water or else he can’t fly through the air in sexual ecstasy with his wife in huge cascades of water. So he’s come to Earth because we have water. It’s like we’re a giant-sized Pleasure Chest store for him. “Be right back honey, I have to pop down to Earth for some lubricant.”

He knows how Earthlings talk and think and what they value. He knows all this because he’s been watching our television for decades on his home planet. He knows we’re motivated by greed and materialism and he’s got a plan to use that greed to make a pile of money and — and — well again I’m less clear on that.

After many decades of living on Earth and building his fortune, he builds a spaceship to go back home. What his plan is, I don’t know. He’s not going to bring back a ton of water to his waterless planet and we’ve seen that his wife and children are already dead.

Now that I think of it, what’s going on on Newton’s home planet? There seem to be only three people living there, his wife and kids. They don’t have a house or food, all they have is a charmingly home-made papier-mache beehive with sails that trundles along on a track. Yet somehow they got it together to send Newton to another planet, so presumably there’s a space center somewhere with rockets and a launchpad and people running it and all that stuff you need to send people into space. Otherwise, why wouldn’t Newton just bring his wife and kids along?

But no, they stay behind and never age, because apparently the folks on Newton’s home planet don’t age, even the children remain the same size for decades. And they wait by the trundling beehive, because — because — well I’m not clear on that either. I think the trundling beehive is the planet’s mass-transit system, but since the beehive has stopped permanently in one spot there doesn’t seem to be much reason to wait there for Daddy to come home.

Anyway, after a very long time, Newton compiles his wealth to build a spaceship to get back home. I don’t know what he’s going to do once he gets home, maybe he’s just a scout for Earth and he’s setting up his gigantic corporation so that he can start bringing his people here and have them live in splendor.

Just as he’s getting ready to get on his spaceship to go home, he gets kidnapped by — by — by an evil somebody, and his patent attorney is killed by the same evil somebody. It’s unclear. Is it another corporation, is it the government? Somebody wants to derail Newton’s plans and they will stop at nothing to do it.

Newton is placed in exile in a hotel under guard. He is studied by scientists. The scientists seem both convinced that there’s nothing unusual about Newton and convinced that he is an alien. In any case they make him very uncomfortable and he has no choice but to take comfort in large amounts of gin.

Eventually everyone loses interest in him and he escapes out into the world. He makes a recording to be broadcast into space where his wife might hear it. We never hear the recording but I’m guessing the message on it is something like: “Dear Wife: had a plan to use human greed to get water to us so we could havesex again but got screwed over by the same human greed I was hoping to exploit. Never coming back. Sorry. Best to the kids. PS: Don’t wait by the Beehive Station lying in the sand for decades — for God’s sake GO HOME!”

Strictly speaking, the movie falls into science-fiction, but as we can see, it is not the nuts-and-bolts wing of the genre but rather the spiritual/societal analysis wing. Indeed, the movie is content to explain very little at all, in spite of being well over two hours long.

The production design is perfunctory. Newton’s inventions, which are supposed to be futuristic and amazing, are clunky, ugly and unappealing. His rocket-building center is housed within a grain-elevator complex with nothing but chain-link fences for security. Decades pass within but it remains steadfastly 1976. Earthlings get old and grey and fat but records are still pressed on vinyl and cost less than five dollars, men still wear polyester leisure suits, and Newton even drives the same car throughout. It’s as though Newton’s arrival on Earth brought the evolution of human design to a screeching halt.

The movie’s strategy of ignoring explanations has its strengths. It’s moody and jarring and elusive, and Bowie is cooler than cool as the slowly dissipating visitor who becomes, alas, too accustomed to Earth ways. In fact, I think that’s the real point of the movie after all, not to tell the story of aliens and government conspiracies but to dramatise the story of an idealistic young man who enters the world with a clear purpose and to show his increasing anxiety at being co-opted, distracted and annihlated by the inevitable crushing forces of capitalist greed and human frailty. (Bowie, apparently, felt a strong connection to the character — he used images from the movie on two consecutive album covers — but did he realize that he, too, would eventually become human, falling from stardom to mere showbizhood? Or is that, in fact, the subtext to his performance?)

This being the 70s, there’s also lots of nudity.

David Bowie would later reprise the “weird guy with a miraculous invention” role in The Prestige. Rip Torn, who plays the only guy who knows Newton’s secret, would reprise the “guy who knows there are aliens on Earth” role in the Men in Black franchise.

The Criterion edition helpfully includes a copy of the original novel, which I have not read, but which I presume holds many of the answers to the movie’s narrative ellipses.

Brice Marden update

There’s a piece in the recent New Yorker about the Brice Marden show at MoMA that, unsurprisingly, is more coherent and better written than my own thoughts.

Zelig

A bold complex experiment, a polished, effective comedy and a brilliant, thrilling, fascinating, staggering achievement. A mockumentary before the term existed, this movie shatters the boundaries of what mainstream entertainers should be capable of delivering to the public. It’s hard to imagine another filmmaker of Woody Allen’s generation (Clint Eastwood, Francis Coppola, even Martin Scorsese) getting anywhere close to the daring, peculiarity and audacity of this project (appropriate enough for a movie the theme of which is people refusing to do what others expect of them).

I’ve seen this movie a dozen times and have made a mockumentary of my own and with the exception of exactly two shots, I haven’t got the slightest clue as to how Woody Allen pulled this thing off. I wish someone would write a book about the movie and its development from concept to script to shooting and into editing. Were all the plot elements in place when the picture went before the cameras, how did the documentary aspect of the project come into focus as the post-production went on, how much of the footage had to be created and how much was lucky finds?

With technical fireworks as dazzling as this, it’s easy to overlook how great the acting is in this movie. Special note goes to the actor playing the elderly modern-day Mia Farrow, who has almost as much screen-time as Farrow herself and whose every remembrance is given just the right spin of humility, self-aware humor and grace.

Everything is utterly convincing, even when it’s absurdly comic. In a time when mockumentaries are common (one is currently a smash boxoffice hit) and look increasingly unconvincing (Borat is funny as hell but is unconvincing as a documentary — why on earth would some of its events be filmed?), it’s truly impressive to see one where everything from extensive, elaborate production design to precise, detailed extras casting to the grain and scratches on the fake old film is exactly right.

The movie I’m working on, The Bentfootes, contains less authentic detail than any given five minutes of Zelig, a fact I can live with only when I consider that our budget is probably less than the money spent in any given five minutes of the two years it took to shoot and edit Zelig. To watch this movie as a filmmaker is to feel one’s feet turn to clay.

Ad Men

(An ad agency. AD MAN and four lackeys.)

A. Guys, good work. We finally have our first million-dollar campaign. Let’s hear it for us.

ALL. HUZZAH!

A. Enough gaiety. We have serious work ahead of us. We hit a bullseye on this, we’ll be sitting pretty for the next one thousand years. We have to write nothing less than the catchiest jingle ever written. Can we do it?

ALL. AFFIRMATIVE!

A. The product is Hot Dogs.

1. What?

2. Hot dogs.

3. What?

A. Hot Dogs. Armour Hot Dogs. Jim, whaddaya got?

1. Hot dogs are a very popular product. We should have no problem identifying our market and pitching to it. But here’s the job: The Armour corporation wants to skew their demographics to a more youthful profile. It is their desire that Armour Hot Dogs be the primary choice among young humans age three to eleven.

2. Kids.

A. Precisely. But they also want to identify specific elements within that demographic and pitch directly to them. So as you can see, we have our work cut out for us.

ALL. Hmmm.

2. Hot dogs.

3. Armour Hot Dogs.

4. What kind of kids like Armour Hot Dogs?

A. That is precisely the question we need to ask. “What kind of kids eat Armour Hot Dogs?”

2. I have no idea.

3. Geez, this is a tough one.

4. It’s maddening. What kind of kids do eat Armour Hot Dogs?

A. That’s what we need to figure out. We have to sharpen our brains, roll up our sleeves and TOUGH THIS THING OUT.

4. BUT WE DON’T KNOW!

A. WE HAVE TO KNOW! THIS IS OUR WORK! Now THINK! THINK! WHAT KIND OF KIDS EAT ARMOUR HOT DOGS!

(Pause.)

1. Fat kids?

(Pause.)

A. Fat kids. Fat kids? Fat kids. Yes. Fat kids probably eat Armour Hot Dogs. Obese children, in all likelihood, have a predilection for eating Armour Hot Dogs. Good. Good! Who else?

2. Skinny kids?

A. It’s a little obvious, but good. Skinny kids, sure. Who else?

(Long pause.)

3. Kids engaged insome sort of activity?

A. Damn it Kyle, we have to deal in specifics here! WHAT kind of activity?

3. Kids who, kids who — build furniture for a living?

4. Kids who collect rare specimens of insects!

2. Kids who write provocative first novels!

1. Kids who manufacture internal combustion engines!

A. No, no — these are all good, but we have to keep it simple.

4. Kids who defecate.

A. Not that simple.

3. Kids who grow old and die.

2. Kids who do their own shopping.

A. NO NO NO! These are the lamest ideas I’ve ever heard in my life! NOW COME ON! WHAT KIND OF KIDS EAT ARMOUR HOT DOGS!

(Pause.)

1. Kids who…climb…on…rocks?

(Pause.)

A. Okay. I’ll buy that. Who else?

2. Tough kids.

A. Good! Now we’re cooking with gas! Who else?

3. Latent homosexual kids!

A. Hm. I like the direction, but it’s got too many syllables.

4. Potentially homosexual kids.

A. No! ARE YOU LISTENING?

1. “Maybe gay” kids.

2. “Kids who might be gay”.

3. “Kids in doubt of their sexuality”.

4. “Kids who go both ways.”

A. Hm. That’s close. Let’s come back to it. Who else?

(Pause.)

1. Kids with infectious diseases.

A. Jim, don’t be a jerk. What did I say before? We can’t give them a phrase like “Kids With Infectious Diseases.” What the hell does that mean? We have to be SPECIFIC! What KIND of infectious diseases?

2. Cholera?

3. Bubonic plague?

4. Amebic dysentery?

1. Not infectious. Epstein-Barr Virus.

A. Wait. That’s good. “Kids with Epstein-Barr Virus love Hot Dogs.” Man. That’s so close. But it’s not good enough. Don’t you see? This jingle has to be PERFECT. And if we have to stay here all night, we will MAKE IT SO. So roll up your sleeves and grab a cup of coffee, because we’re in for a bumpy ride.

(Blackout. Pause.)

(Lights up. Much later. It’s been a long night.)

1. Polio?

A. No.

2. Spanish influenza?

A. No.

2. It was real big in 1918.

3. Yellow fever?

A. No.

4. Anthrax!

A. Better but no.

1. Malaria.

A. No.

2. Whooping cough.

A. No!

2. No, we could even say it funny: “WHOOPing cough!”

A. No.

3. Rubella.

A. No, they have a cure.

4. Swine flu.

A. No no no. These are all bullshit. We have to get serious here. This should be a disease that’s essentially harmless to children, but extremely dangerous to their parents.

1. Measles.

2. Mumps.

3. Spastic colitis.

4. Blastomycosis.

1. Botulism!

2. Diphtheria!

3. Encephalitis!

4. Gonorrhea!

1. Hepatitis!

2. Herpes simplex!

3. Histoplasmosis!

4. Hookworm!

1. Mononucleosis!

2. Pertussis!

3. That’s whooping cough. Scarlet fever!

4. Spotted fever!

1. Syphilis!

2. Tapeworm!

3. Toxoplasmosis!

4. Trichomoniasis!

1. Chicken pox!

2. Typhus!

A. Wait! Go back.

2. Typhus?

3. Toxoplasmosis?

4. Trichomoniasis?

A. No! No!

1. Chicken pox?

A. Chicken pox. Chicken pox. Wait. “Even kids with Chicken Pox Love Hot Dogs.”

(Pause.)

No.

(General disappointment.)

What was the last one I liked?

1. Lyme disease.

A. Fuck it. We’ll go with that. Let’s get the hell out of here.

Soylent Green

WHAT DOES BIG BROTHER WANT? Big Brother wants only to feed the world. Who doesn’t want to feed the world? Go Big Brother!

WHAT DOES THE REBEL WANT? The rebel wants only to solve the murder of Joseph Cotten. Who wouldn’t want to solve the murder of Joseph Cotten? Go rebel!

WHAT DOES THE REBEL GET? The rebel does, indeed solve the murder of Joseph Cotten. And a whole lot more.

IS THERE AN UPPER CLASS, AND DO THEY HAVE ANY FUN? There is and they do. They have clean apartments, soap, hot water, towels, alcohol, you name it. Fun ahoy!

DOES SOCIETY CHANGE AS A RESULT OF THE REBEL’S ACTIONS? Well, he sticks a defiant, bloody hand in the air and says “Somehow we’ve got to stop them!” before he’s carted off to Waste Disposal, so I guess that counts for something.

NOTES: By far the best-constructed, most entertaining of the Charlton Heston sci-fi world-gone-wrong trilogy. Like Blade Runner and Minority Report, it tells us its skewed worldview through the guise of a detective story. It’s not a very complicated detective story, but the sheer level of detail brought to the worldview is convincing and pervasive. It’s not so much the physical details — the design world, in 2022, has ground to a dead halt in 1973 — but the characters’ attitudes, the sheer level of acceptance everyone has of “well, this is how the world is.” This is introduced most vividly in the opening assassination scene — the assassin isn’t a bad guy and neither is the victim; one’s been hired to kill the other and they both just kind of sigh and get on with it. That stunning scene sets the tone for the whole movie: people just kind of accept living in cars, or having to pedal a bicycle for their own electricity, or having dozens of homeless people living in their stairwell. Women just kind of accept being treated as chattel and having police detectives ransack their house, stealing everything that isn’t nailed down. The poor just kind of accept that there will be shortages, and when they riot, they just kind of accept that the police will respond with bulldozers. It’s not pleasant, but what are you gonna do? Everyone, rich and poor alike, just kind of accepts that everything is rotten and there isn’t anything you can do about it. It’s the apathy in the movie that gets to you, not the production design, and it shows how a single idea and a mastery of tone can go a long way toward carrying a movie. Because, let’s face it, the detective story in this movie is practically nonexistent. The protagonist barely does any detective work at all; he punches people and asks them what’s going on while his elderly pal reads books and then goes asks somebody what’s going on and then they tell him. There is no puzzle or layers of intrigue, rather it’s riddled with cliches (the detective gets involved with the doomed dame, pursues the hot case too far and catches heat from his superiors, blah de blah de blah). The triumph is all tone and the looks on people’s faces. When Chuck Connors shoots a priest in the head in a confessional, neither party seems surprised or even particularly uspet by the encounter.

It’s a shock to hear phrases like “Greenhouse effect” tossed around in a movie made in 1973, especially when the result of that effect is the world described here. The whole thing seems creepily plausible, a world where an assassin has to go to a special contact to acquire a meathook but has no trouble getting a handgun.

Edward G. Robinson’s performance is as good as everyone remembers it and in a way, Soylent Green is a love story between Heston and Robinson, just as Double Indemnity is a love story between Fred MacMurray and Robinson. I guess he was just that lovable.

Special bonus points for this movie for having Dick Van Patten realize his potential as an actor by appearing as a suicide assistant.

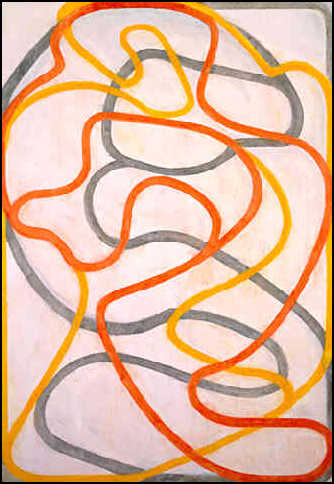

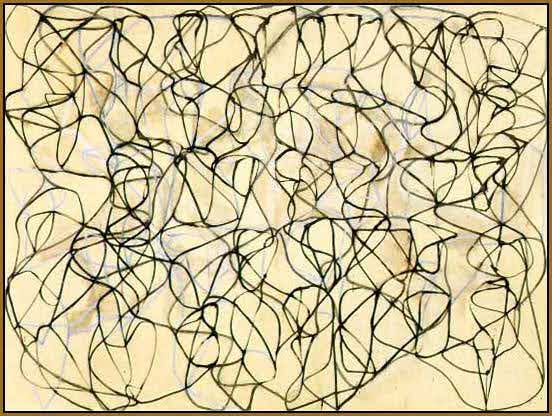

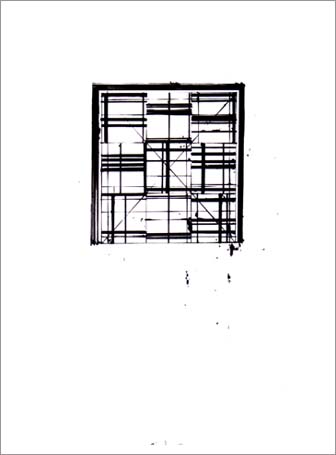

Brice Marden

Brice Marden, America’s greatest living painter, has what I believe is his first full retrospective of his work showing at MoMA right now through mid-January.

If you care anything about abstract art or American painting, or if you have a soul, I encourage you to see this show.

Yes, that’s right, when I’m not dissecting TV shows, writing movies about talking bugs or watching movies about futuristic utopias, I can often be found strolling about the world’s institutions of modern art, searching for dramatic collusions of lines and colors.

I was not always like this. I used to think abstraction was a fraud. I didn’t “get” it, I thought the artists were either delusional, working under an exaggerated or even fabricated sense of their own importance, or else laughing at us as we gazed in confusion at their messageless works.

Brice Marden changed all that.

I still remember quite clearly when it happened. About 10 years ago I was in Cambridge with my bride-to-be and I stopped in at the local art joint to see a couple of Sargents they had on display. I never got as far as the Sargents because there was a show of Brice Marden drawings on the first floor. They were opaque and confounding, yet lyrical and intriguing at the same time. They were, I found out, drawn with anything but a pen — Marden will use twigs or shells, dipped in ink and held at a distance, to keep his line naive and undisciplined — and utterly bewitching. They looked like trees or vines or hedges or something, but they were both that and not that; they were both representative of things and also just marks on paper. And suddenly I “got” abstraction. In fact, I suddenly understood what the word “abstraction” means.

And the floodgates were opened. Suddenly I “got” Pollock and DeKooning, Sigmar Polke and Gerhard Richter, Barnett Newman and Cy Twombly (O! Cy Twombly — for added value, there are also a half-dozen crucil, essential Cy Twomblys hanging in the Big Gallery space at MoMA). And I went from being a guy who thought abstraction was a fraud to being a guy who now can barely tolerate representation — I keep thinking a representational artist is trying to sell me something. And now I’m the kind of guy who drags reluctant friends and family to places like the Dia Center in Beacon NY to see Richard Serra’s Torqued Ellipses (I’m still cursing myself for not getting to Houston for the Twombly show a few years ago). Now I’m the kind of guy who stops to look at a crack in the sidewalk or a badly-painted wall or a carelessly-whitewashed window. For me, a painted surface is now filled with light, a line brings in drama and a whole bunch of lines, artfully arranged, can produce an almost unbearable tension.

You may hate the Marden show. When I was there today there were plenty who did. Galleries were dotted with confused middle-aged women and disgusted middle-aged men, wavering between not being sure if they were being conned and utterly sure they were being conned. The men were particularly angry about it, sniggering to each other, voicing their moral superiority, muttering threats to the artist and, in one case, even wishing him a violent death. I’m not sure what provokes a reaction like that, I don’t know what one is expecting when one comes to the Museum of Modern Art. It seems to me that someone who sees a show as positive, life-affirming and glorious as this and reacts with a wish of violence upon the artist probably shouldn’t bother walking into an art museum in the first place.

UPDATE: Thanks everyone for writing in. For the folks who hate this stuff, let me reiterate, I used to hate it too. Now I don’t and this guy is the reason. I’m not an art historian, I’m not a theoretician and I’m sure as shootin’ ain’t no elitist. He opened up a whole new artistic world for me and I’ll never forget it.

And for those who like this stuff, here’s a few more. Thanks again!

Gattaca

WHAT DOES BIG BROTHER WANT? Well, there is no “Big Brother” per se, but society wants perfection, and it knows how to get it.

WHAT DOES THE REBEL WANT? Same as anybody, to go into space. I think “space” here represents “heaven.” The protagonist has been damned by unfortunate birth to hell; he’s going to fool the gatekeepers of heaven into letting him slip by.

WHAT DOES THE REBEL GET? With the aid of an unfortunate perfect-guy (who condemns himself to flames of perdition just as the protagonist is lifted into heaven), plus the love of a beautiful woman (nothing, NOTHING is accomplished in a Futuristic Dystopia without the love of a beautiful woman), plus the last-minute good will of a company doctor, he gets his wish.

DOES SOCIETY CHANGE AS A RESULT OF THE REBEL’S ACTIONS? Revolution isn’t really the protagonist’s goal here, and not even escape really. He wants to belong; he wants to know he’s good enough to go to heaven. The screenwriter chose the term “Valid” for a reason.

NOTES: The theme of the movie, it seems to me, is Will. Does the protagonist have sufficient will to achieve his goal? Does he have what it takes to overcome his genetic predisposition, switch identities with another guy, keep up the ruse for years, endure loneliness, constant, obsessive vigilance in cleanliness, break his own legs, live with Jude Law?

The fimmakers face a problem, of course: genetic science and astrophysics are dull, cerebral subjects. How to juice up the narrative and compel audience interest? MURDER! MURDER MOST FOUL, that’s how. And so, on his way to the stars, our protagonist gets caught up in a murder investigation that seems important only to the police. Indeed, no one seems interested in or excited by anything in this sterile, unpopulated future; to be excited, I suppose, would be to be less than perfect, which everyone is, or pretends to be.

Our protagonist is totally obsessed, to a ridiculous degree, with getting to the stars, and yet, with days to go before launch and a murder investigation breathing down his neck, he decides to take a chance in romancing Uma Thurman. This in spite of the risk of exposure, the unhygenic quality of sexual contact, the possibility of getting “girl germs” and the fact that Uma doesn’t seem to have much of a pulse. Perhaps he feels that if he can’t reach the stars in heaven he can at least have one in his bed on Earth.

Then, cleared from his murder investigation, given a clean bill of health from his corporation, and ready for launch, the protagonist must still face down his brother/detective for one last suicidal swim. Boys, as the saying goes, will be boys.

One of my posters pointed out in the previous entry that the society of Gattaca is filled with genetic flaws despite science’s best efforts, but I’m not sure that’s what the movie is trying to say. There is the usual assortment of Valids and In-Valids in society it seems, and they all seem to get along okay, although the Valids seem to lord it over the mutts a little bit. There is the six-fingered pianist, but it’s unclear from the script whether the pianist is a genetic freak or a planned accident — that is, is he another kind of outsider, like the protagonist, an In-Valid who has overcome his genetic deformity to find a place in Valid society, or did his parents actually give him six fingers on purpose so that he could become a great pianist? “That piece can only be played with six fingers,” says Uma, indicating that the piece in question was composed specifically for someone genetically modified.