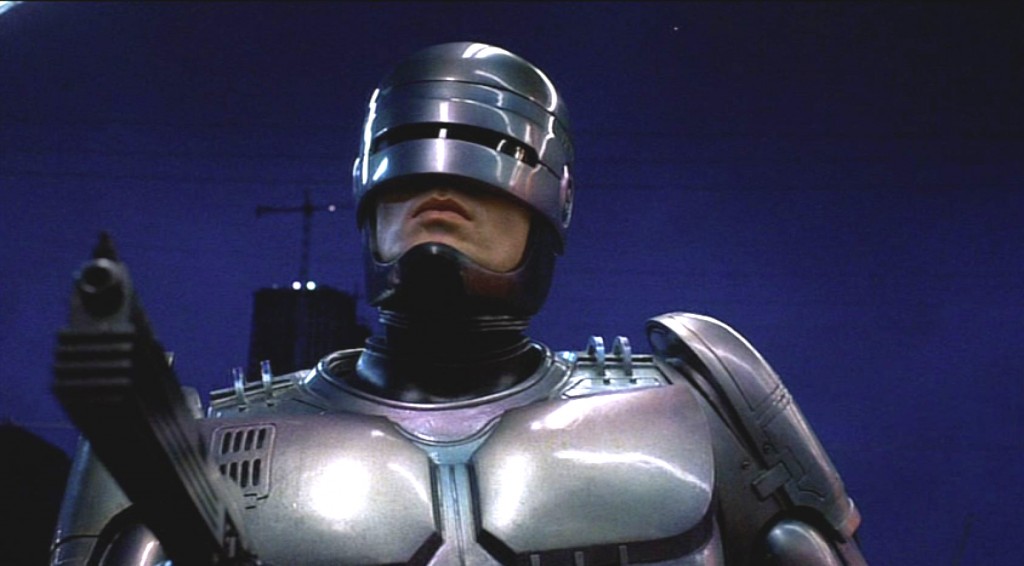

Favorite screenplays: Robocop part 5

It warms my analytic heart when filmmakers announce act breaks with devices, and Robocop does not disappoint. Each act begins with a news report and attendant commercials (as news is, lest we forget, just another form of entertainment in a corporate oligarchy). Act III begins with a commercial for a car, the 6000 SUX, done in the style of The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, yet another low-budget film reference to let cinephiles know they’re dealing with a self-aware, intelligent satire. The dinosaur in the car commercial terrorizes the city streets until it’s dwarfed by the advertised car. The joke, of course, is not just that the car is huge, but that the huge car out-dinosaurs an actual dinosaur. (It’s also fueled by dead dinosaurs, if you want to take its dominance that far.)

Favorite screenplays: Robocop part 4

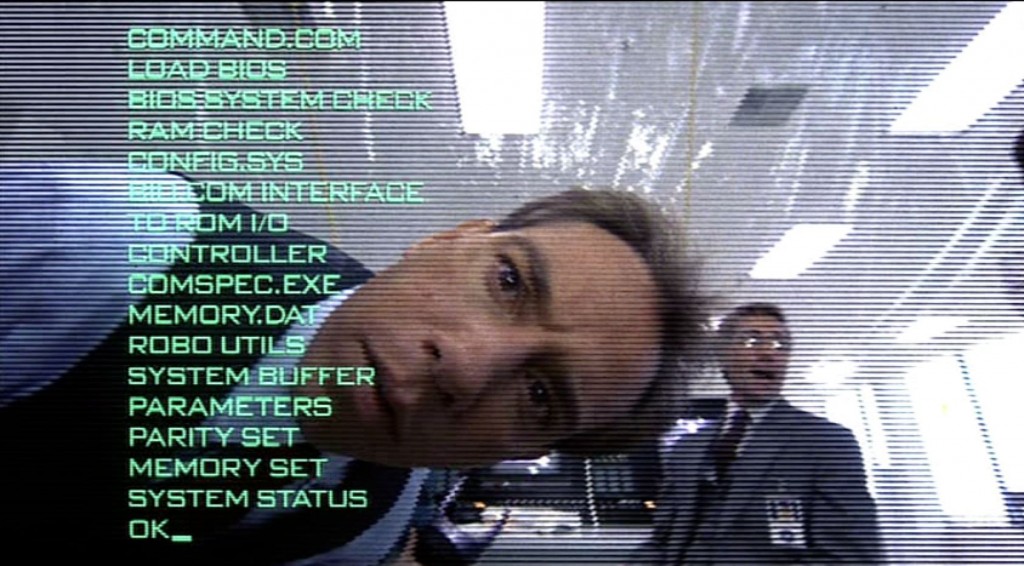

I did something of a disservice to Murphy when I said he gave up his protagonist status at the beginning of Act II of Robocop. What happens is something a little more subtle. Lots of superheroes undergo a transformation at the end of the first act of their origin stories, but few completely forget their previous identity. What happens to Murphy is that he falls into a kind of slumber, and in that slumber he dreams of being the kind of cop he’s always wanted to be: strong, resourceful, unfailingly just, and wicked cool. He wants to be TJ Lazer, essentially, he wants to be a TV cop, and Morton’s Robocop program gives him the chance to do that. The price he pays is his identity as Murphy, good husband and father. This is, the screenplay suggests, the bargain we all make when dealing with a corporate oligarchy: we gain a smidgen of that corporation’s power, but we give up our total identities as individuals in return. At the supply side, we become product, at the demand side we become consumers.

Favorite screenplays: Robocop part 3

Act I of Robocop begins with a television show, and contains references to other television shows. Act II also begins with a television show, except this time the viewer is the camera and the show is the real world. We are through the looking glass, as it were, in our view of this futuristic dystopia. Again, the exposition is delivered straight to the viewer and with plenty of wit and satire to lighten the load.

Favorite screenplays: Robocop part 2

Murphy is a simple man who has been drafted into a complex, dangerous world. When we catch up with him at the fourteen-minute mark, he’s practicing his gun-twirling. Why is he practicing his gun-twirling? Murphy explains to spitfire partner Lewis, because there is a cop on TV, T.J. Lazer, who is a “good cop,” and whom Murphy’s son loves. So in the space of twenty seconds or so, we learn that Murphy is a dedicated father, loves his son, wants “to be good” for the sake of that son. The bashfulness with which he describes this intimacy to Lewis indicates that he is also in love with his wife. This is without staging a “family scene” that would dramatize all this. Again, that’s probably due to budget, since the screenplay is telling instead of showing, but it has a dramatic payoff: the screenplay, like Murphy, at this point takes his happy family for granted. He’s good, his son is good, his wife is good, he sees people as good, he’s about to get a lesson in how bad people can be. Like Jason Bourne, Murphy will be forced to rediscover who he is, and for the most part the viewer will be put in the place of the protagonist, which is an ideal place for a viewer to be.

Favorite screenplays: Robocop part 1

The first and last question of any screenplay is “What does the protagonist want?” But sometimes it’s necessary to first define the world the protagonist lives in. This can be done a number of ways. In the low-budget movies of Roger Corman or William Castle, sometimes the movie begins with a simple monolgue straight to the audience. It’s cheap but effecient, and it forges a bond with the audience that “cooler” movies don’t. The filmmaker, in effect, makes a deal with the audience, saying: Look, I don’t have a big budget or fancy stars, all’s I got is ideas, work with me here.

Robocop isn’t quite that low-budget, but it does the next-step-up version of that: it opens with a TV news report. The smiling TV anchors tell us the days news: South Africa is going nuclear to preserve white control of the country, the president of the US stages a press conference from the orbiting space station with hilarious results, and police officers in Detroit, which has a privatized police force, are being slaughtered by a group of ruthless gangsters. The TV report, revving for maximum efficiency, goes so far as to name the movie’s chief antagonist, Clarence Boddicker, and its secret ultimate bad-guy, Dick Jones. Jones, the new leader of the new corporate-owned Detroit police force, expresses no sympathy for the policemen slaughtered on his watch. “If you can’t take the heat, stay out of the kitchen,” he advises any police officers who might object to being out-gunned by madmen. The TV news report also lays in a layer of knowing satire on the narrative, letting us know that it’s going to look at this world from a skeptical stance. It accomplishes the same thing as the Corman voice-over, it takes the audience aside and lets it know, quickly and cleanly, its attitude toward its genre and narrative.

(Speaking of low-budget exploitation movies, I assume Clarence Boddicker is named for Budd Boetticher, the great director of tight-lipped westerns.)

Some thoughts on The Lone Ranger

What does the Lone Ranger want? Excellent question! Of necessity, spoilers within.

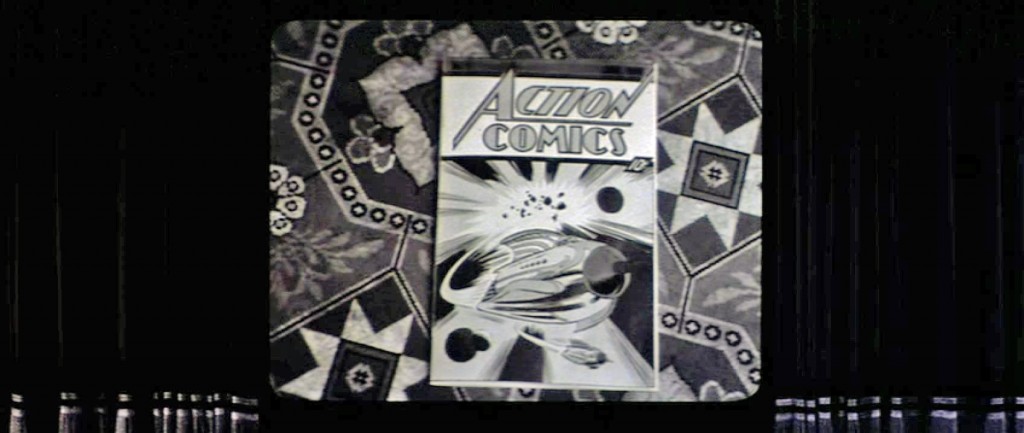

Superman: Superman: The Movie part 1

The thing to remember about Superman: The Movie is that it was the first of its kind. Made in 1978 by middle-aged men, it was poised between nostalgia and hipness, gravity and camp, cutting-edge verisimilitude and old-fashioned Hollywood spectacle. It wants to take its subject matter seriously, but can’t quite commit to it fully.

I was 17 when it came out, and theoretically its target audience. The advertising, John Williams score and space-bound title sequence made it clear that it was going after the Star Wars audience, which included children who didn’t know about Buck Rogers serials and nostalgic grownups who did. Having never read the comics, my concept of Superman in 1978 was limited to the syndicated reruns of the George Reeves show from the 1950s (which had borrowed heavily from the radio shows of the 1940s). The stunning Fleischer Superman shorts were a long-gone artifact at that point, not yet available at the counters of every drugstore in America. Only one, “Superman and the Mechanical Monsters,” had been shown to American audiences in recent decades, in the 1977 Fantastic Animation Festival, which was, in and of itself, a cultural touchstone in the pre-cable days of American geekdom.

The George Reeves show never went to Krypton or dwelled on Superman’s tragic backstory (much as the 1966 Batman show never once mentioned why Bruce Wayne dresses up as a bat to fight crime), so the idea of a movie presenting, with grandeur, “serious” actors, a large budget and state-of-the-art special effects (that look laughably terrible today) was breaking new ground for a viewer like me. And the first couple of acts really hammered home the weighty mythology and came to form the idea of Superman in the minds of my generation.

So the movie opens with a shot of curtains opening to reveal a 1930s movie screen, with standard 1:33 aspect ratio. The curtains, in an of themselves, were significant in 1978 because that was the moment that multiplexes were exploding, and curtains in movie theaters were becoming a thing of the past. The curtains in the movie palace were there to remind the audience of the ritual of the theater, of the glamour that awaited the audience on the other side of those curtains – the multiplex did away with glamour and ritual. They turned moviegoing into a transaction, not a passport to adventure. By opening with a shot of curtains, black-and-white curtains at that, the movie seeks to frame its presentation in a sense of tradition, of promises made and kept.

(The theater where I saw Superman was, in fact, a converted vaudeville house from the 1920s, complete with stage, dressing rooms, orchestra pit and fake “Spanish Piazza” decor. When the curtains opened to reveal a movie that begins with curtains opening, it made the moment doubly somber.)

Venture Bros history

It’s my intention to take up analyzing the Venture Bros episodes as they are aired, so I found this especially helpful.

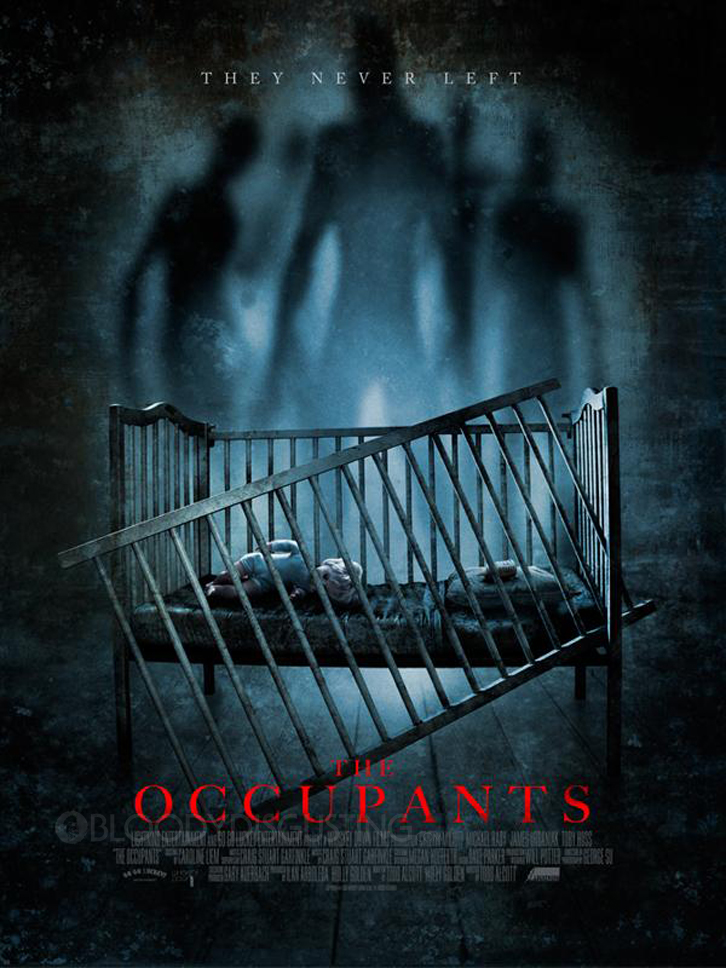

Blood Relative update

Keen readers of this journal will recall that, a couple of years ago, I wrote and directed a low-budget horror movie called Blood Relative. Things being as they are in the world of low-budget horror, it took a while to finish the thing and then it took another while to get a distributor. Now it has one, and boy are they doing their job! They’ve changed the title (which I like) and they’re taking it to Cannes! You can watch the sales trailer here!

Snow White: The Missing Scene

Finally, a key scene from Walt Disney’s classic is presented, filling in the missing piece of “the fairest movie of them all.”