Favorite screenplays: Robocop part 1

The first and last question of any screenplay is “What does the protagonist want?” But sometimes it’s necessary to first define the world the protagonist lives in. This can be done a number of ways. In the low-budget movies of Roger Corman or William Castle, sometimes the movie begins with a simple monolgue straight to the audience. It’s cheap but effecient, and it forges a bond with the audience that “cooler” movies don’t. The filmmaker, in effect, makes a deal with the audience, saying: Look, I don’t have a big budget or fancy stars, all’s I got is ideas, work with me here.

Robocop isn’t quite that low-budget, but it does the next-step-up version of that: it opens with a TV news report. The smiling TV anchors tell us the days news: South Africa is going nuclear to preserve white control of the country, the president of the US stages a press conference from the orbiting space station with hilarious results, and police officers in Detroit, which has a privatized police force, are being slaughtered by a group of ruthless gangsters. The TV report, revving for maximum efficiency, goes so far as to name the movie’s chief antagonist, Clarence Boddicker, and its secret ultimate bad-guy, Dick Jones. Jones, the new leader of the new corporate-owned Detroit police force, expresses no sympathy for the policemen slaughtered on his watch. “If you can’t take the heat, stay out of the kitchen,” he advises any police officers who might object to being out-gunned by madmen. The TV news report also lays in a layer of knowing satire on the narrative, letting us know that it’s going to look at this world from a skeptical stance. It accomplishes the same thing as the Corman voice-over, it takes the audience aside and lets it know, quickly and cleanly, its attitude toward its genre and narrative.

(Speaking of low-budget exploitation movies, I assume Clarence Boddicker is named for Budd Boetticher, the great director of tight-lipped westerns.)

Into this situation walks Murphy (the most common surname in Ireland), who’s just been transferred from the south side of town to the west. For the purposes of this narrative, the south side of Detroit is apparently a garden paradise, while the west is, well, the “wild west.” Things are bad in this neighborhood controlled by Boddicker, and a strike is looming. In moments, we learn that police officers, unlike other workers, have a duty to remain working no matter how dangerous the job. The notion of a privatized police department was science fiction in 1987, but today it seems like a genuine possibility. And when the police department is run for profit, why not squeeze the workers? Who would strike? And how easy would it be to stop a strike that starts? A privatized police force is a unique and frightening possibility, and Robocop gets the grim reality of that possibility across with brutal efficiency, and in less time than it takes to read what I’ve just written here.

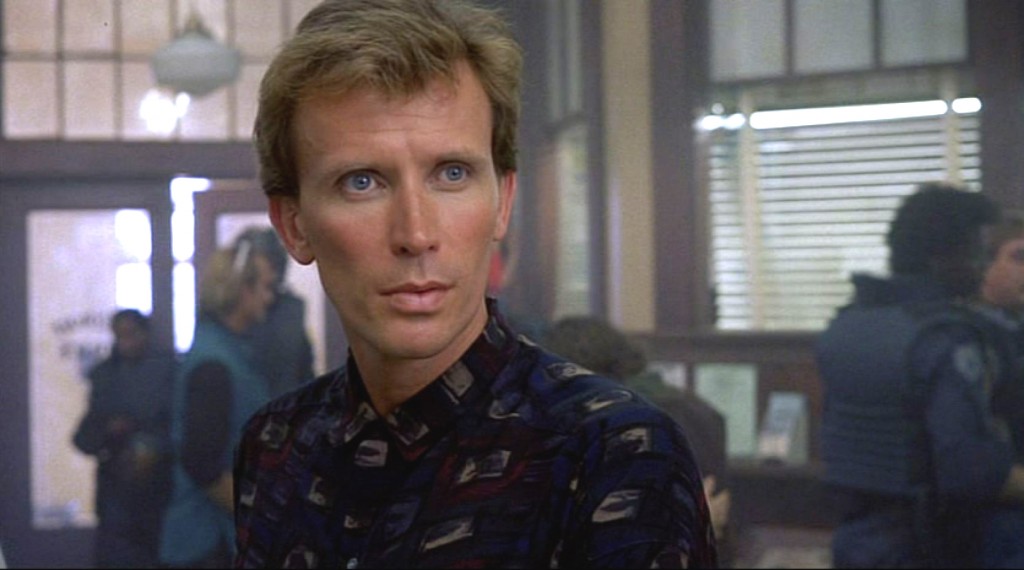

The lanky Murphy is teamed with spunky spitfire (lady-cop!) Lewis. What does Murphy want? At this point, it seems, “to do his job.” He doesn’t seem to have an opinion or agenda on his first day on the job in Metro West. He insists on taking the wheel of the patrol car, a minor aggression against his partner Lewis, but his blue eyes and straight-ahead attitude make Lewis, and the viewer, hold off on judging him. Right now, Murphy is deferential but firm in his insistence on being taken seriously.

It’s Murphy’s first day on the job, but the people who actually run the city have plans they’ve been making for decades. In a dense, hilarious, brutally efficient scene, The screenplay next pulls back the curtain and we go behind the scenes to the high-rise conference room where we meet the heads of OCP, the corporation that has bought the Detroit police department. In order of rank, there is The Old Man, Dick Jones and Bob Morton. The screenplay lays out their positions and their wants in the context of lethal corporate politics, the cutthroat comedy leavening the tons of exposition being presented. It’s a long scene, over six minutes, but packed with scale, humor, character beats and vicious satire.

The Old Man has a dream: a re-built Detroit called Delta City. Is The Old Man evil? Doesn’t seem so. The Old Man (who represents, for the purposes of this satire, “the old ways”), it seems, genuinely wants to breathe life into rotted Detroit. That, to him, means eradicating crime so that the city can proceed with bringing in workers and reviving the economy. Good for The Old Man! But there are different visions of eradicating crime, and The Old Man’s underlings are in a constant jockeying for position to implement their visions. Dick Jones wants his branch of OCP, Security Concepts, to get a municipal contract to produce the ED-209, a gigantic lethal law-enforcement robot. Ultimately, Dick Jones’s plan is to make himself so vital to the infrastructure of OCP that he will replace The Old Man. Meanwhile, Bob Morton, who, if anything, is less principled than Dick Jones, simply wants advancement and perceives that Jones’s ED-209 program is low on The Old Man’s priorities.

The hulking ED-209 is certainly imposing, but it takes no time for Jones’s demonstration to go haywire as ED-209 oversteps the bounds of its programming and brutally murders an OCP board member. To add insult to injury, the murdered man, in his dying, demolishes The Old Man’s model for Delta City. That, it would seem, would be the end of the ED-209 program, but corporate infighting knows no bounds.

The Old Man, to his credit, is aghast at the board member’s death, but he’s not all humanitarian: he’s also concerned that the ED-209 is bad business: if the giant robots are delayed, the interest payments all the loans OCP has taken out to fund the development of Delta City will cripple the company. Bob Morton, seeing an opportunity, steps in and offers up his own vision of crime-free Detroit: the Robocop program. The Robocop program, we’re told in elliptical corporate-speak, will turn an ordinary police officer into a cyborg. Morton has been profiling potential cyborg officers for months now, looking for a good match. He knows that, thanks to the reign of Boddicker, that a candidate will present himself anon.

Now that the pieces of the narrative have been put into place, all that remains is for Murphy, the laconic cop from the paradisical south side, to step into the action, coming into the crosshairs of competing corporate agendas he has never dreamed of.

“Morton has been profiling potential cyborg officers for months now, looking for a good match. He knows that, thanks to the reign of Boddicker, that a candidate will present himself anon.”

This is the key piece of the story puzzle that eluded me for almost 20 years: the fact that Murphy was transferred into Old Detroit by Security Concepts because he’d be the most likely to put himself in harm’s way. “We’ve restructured the department and placed prime candidates according to risk factor,” says Bob Morton. (This fateful self-sacrifice also bolsters Verhoeven’s Christ metaphor, which permeates this film.)