Favorite screenplays: Robocop part 3

Act I of Robocop begins with a television show, and contains references to other television shows. Act II also begins with a television show, except this time the viewer is the camera and the show is the real world. We are through the looking glass, as it were, in our view of this futuristic dystopia. Again, the exposition is delivered straight to the viewer and with plenty of wit and satire to lighten the load.

Back at Metro West HQ, the harried desk sergeant is dealing with a crazy complainant, who insists that he “takes orders from a higher source,” presumably imaginary. Just then, Bob Morton’s OCP goons march in with their Robocop equipment, taking over the precinct and treating the desk sergeant like an irritant. “Official OCP business,” says Morton, adding helpfully, “Get lost.” The desk sergeant, just like his insane complainant, start to tell Morton who he takes orders from, but stops short when he sees Robocop walk in. The concept of taking orders from higher authorities is key to the remainder of the narrative. Who is in charge in Old Detroit? Is it The Old Man? Dick Jones? Young Turk Morton? Or Boddicker? In a world with privatized law enforcement, whom do the police serve and protect? We see Robocop first employed as a complicated puppet or plaything, a new technological gadget that can shoot like T.J. Lazer, record memories digitally and follow any order from “sit in this chair” to “protect the innocent.” No wonder Morton is so crazy about Robocop, he’s the biggest, best action figure a boy ever had.

Robocop is turned loose into the streets, and in short order stops a liquor-store holdup, prevents a brutal rape and defuses a hostage crisis. His tactics are as brutal as the world he lives in, but apparently stop short of being lethal. Overnight, he is made a superhero, a media star, a children’s role model, a symbol of hope, all things to all people. We learn, through a second TV news report, that Bob Morton is now seen as the savior of Delta City, the “shining city on the hill” to borrow a phrase from Reagan.

Because Murphy has been temporarily removed from the narrative and Robocop is, for all his spectacular ability, a plaything, Bob Morton, for a time, becomes the protagonist, or at least the anti-hero, of the movie, rising through the ranks of OCP, boasting of ridding Old Detroit of crime in 40 days, and incurring the ire of Dick Jones, who, the reader will recall, had staked his career on the ED-209. I don’t know the economics of the ED-209, but Morton’s plan, while efficient, requires the violent deaths of honest police officers to succeed, making Morton the slightly more bloodthirsty of the two corporate schemers. Dick Jones confronts Morton in the executive men’s room, and Jones defends his ED-209 program with some legitimacy: the Robocop program may be successful in the short run, but the ED-209 is designed to be a world-wide profit machine for generations to come. In a lot of ways, Jones’s is the more responsible corporate choice. In this way, Jones represents an older, pre-1980s way of doing business: looking at the long game, building a company. The Old Man is a visionary, Jones plays a long game, but Morton is a typical 1980s tyro, looking to get rich fast and planning to never come down.

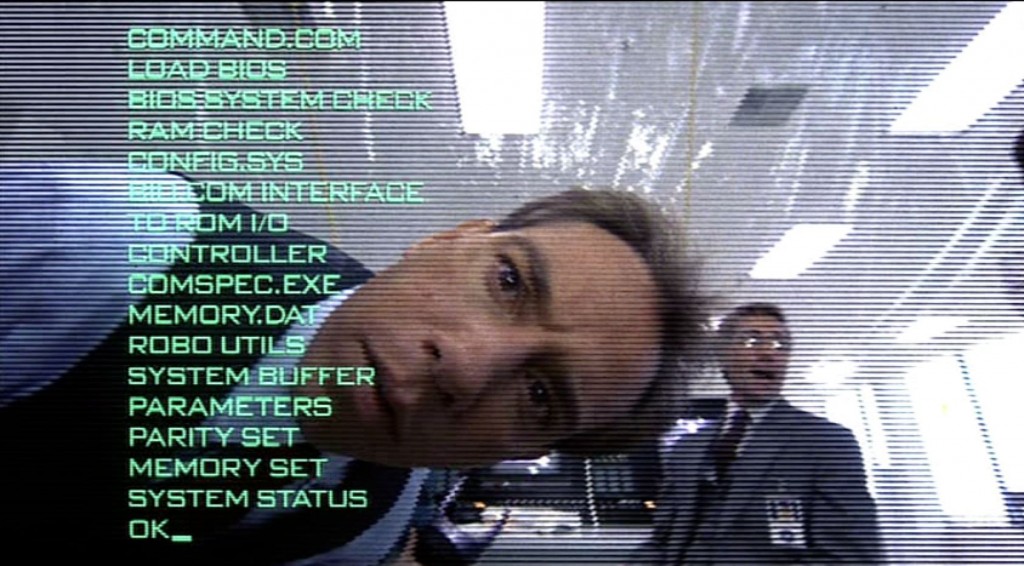

Meanwhile, back at Metro West HQ, what dreams come to the offline Robocop? Murphy’s pre-machine life bubbles, somehow, to the surface, disturbing his sleep. He remembers being tortured and shot by Boddicker and his gang, and he disobeys his first order – the order to sit in his chair while offline – and gets up, heading out into the night to seek justice for the man he once was. Lewis catches up to him – alone among the staff at Metro West, she recognizes him as Murphy. Lewis is Murphy’s route back to his old self, and while she is not his wife or lover, she has shared with him the intimacy of battle – they are blood-brothers. Morton sets Lewis straight: “He doesn’t have a name, he has a program. He’s product.” That, in fact, is the key line of the movie: the world that Murphy wandered into was dangerous not because of drug dealers or bank robbers, but because of people like Morton, who sees people as a means to profits, grist for the capitalist mill. To the desk sergeant Morton says “This isn’t police business, it’s OCP,” answering my earlier question: when a corporation owns the police, the city becomes a capitalist police state.

Isn’t there a Murphy POV scene when a tech guy tells Morton ‘We can save one of his arms,’ and he tells them no? That’s one of more subtly skin-crawling moments in the movie.

I wrote a review of this as a college intern for the Nashville Banner newspaper when it came out, and called it ‘Mad Max Headroom’ for the combination of sci-fi violence and sci-fi media satire.

That scene does indeed happen.