very subtle

A brand new comment left on my Tower Records post, from several months ago:

The question from a new user

Hello everybody! I am new to the site toddalcott.livejournal.com

Could anyone, please, advise if there is a lot of

spam and unscrupulous advertising. Can I trust

all this information, which is present at this forum?

Sorry for stupid questions, I just really want know which

information I should trust or even pay attention.

No, spambot. Please do not pay attention. You cannot trust all the information, which is present in this forum. This forum is filled to the brim with unscrupulous advertising.

I get two or three of these a week, but this is, so far, the most, shall we say, "character driven." Gotta love the viral advertising.

My dream

Attention armchair psychologists:

I didn’t use to be this way, but, for whatever reason, I am this way now.

I have only one dream. Over and over again, every night. The details are always different, but the scenario is always the same.

It’s a variation on The Actor’s Nightmare. The Actor’s Nightmare is that you go out onstage and you don’t know your lines.

This is the dream: I am who I am, Todd Alcott, and my life (or at least my personality) is that of my waking hours. I dress how I dress, I talk to people as I talk to people, I think as I think.

As the dream begins, I have, every night, contracted, somehow, to engage in some sort of a performance — a speech, a monologue show, a TV interview, a play, a symposium. Endless permutations, I don’t know how my brain comes up with them all. Some elements seem pulled from my past, some don’t.

I have contracted to engage in this performance and I am unprepared. Or, actually, it’s not that I’m unprepared, exactly, it’s that, every night, things have been scheduled in such a way so that there is no time for me to prepare. Instead, there is always some kind of complicated hassle about lodging, transportation, costume, location, directions. These complications can become baroque in the extreme.

don’t tell me you don’t want to know how the rest of this goes

Sam hits the nub

Conversation in the car this afternoon with Sam (5):

SAM. Dad?

DAD. Yeah?

S. You know what my favorite food is?

D. What.

S. Lox.

D. I was going to say burritos.

S. I like burritos.

D. How about burritos with lox in them?

S. Eugh! That would be awful!

D. In New York, there used to be a restaurant near our house, they served crabmeat enchiladas. That was my favorite food for a long time.

S. Crabmeat?

D. Yeah, they —

S. Meat? From a crab?

D. Sure, and —

S. How is that fair?

D. What do you mean?

S. You mean they would kill a crab? Just to get it’s meat?

D. Well —

S. That’s not fair! The crab wasn’t hurting anybody!

D. But —

S. I don’t think it’s fair to kill animals just to eat them!

D. O-okay, then —

S. How can people do that, destroy nature, I —

D. But Sam —

S. I don’t like killing animals! It’s not fair and it’s not what nature wants!

D. Okay, sure. Okay. So you think it’s okay to eat fish but not, like, chickens and cows and pigs?

S. No! I don’t think it’s okay to kill animals at all! Nature wants animals to be out in it, to live, and have fun, and make more animals! Nature doesn’t want people to kill all the animals!

D. Um, okay. Okay. (pause) Do you know what lox is?

S. Yeah, it’s salmon.

D. Well, salmon is a fish.

S. Yeah, but those fish are already dead, there’s nothing I can do about that. And, and chicken nuggets, and hamburgers, and bacon, those animals are already dead. What I’m talking about is killing animals.

Rest in peace, Larry “Bud” Melman

It’s difficult to imagine now, 25 years later, the impact the early days of the NBC Letterman show had on us young hipsters. Cable was still a rarity and TV comedy in the days after Monty Python was Mork and Mindy. The 1982 Letterman show was a bizarre, cathartic psychotic freakout of TV culture, a show that took everything that had preceded it and turned it inside-out, and then devoured it, and then shat it out and devoured it again. You could turn on Letterman in 1982 and, quite literally, have no idea what to expect.

(I remember, early on, there was a “wheel of fortune” bit they did where Letterman would spin the wheel to see what would happen next. Selections were all mundane or ridiculous things, but then one choice was “Surprise Visit From Mick Jagger,” and there was a booth onstage with the hand of “Mick Jagger” waving out the top. In 1982, the idea of Mick Jagger showing up for Letterman was a cruel joke; now it would be commonplace.)

One of the high-water marks of the period was the character of Larry “Bud” Melman, a cranky, befuddled old man who was too real to be fake (although, of course, he was fake, an actor named Calvert DeForest). His timing, whether produced by comic brilliance or simple ineptitude, was absolutely stunning, and he could destroy a routine in the blink of an eye, then resurrect it into another realm in the following breath. Letterman would thrust him into situations clearly beyond his comprehension, seemingly to make fun of a sorry old man on national television, and Melman’s palpable haplessness, rage and desperation could become almost unbearable. You couldn’t figure out why Letterman kept using this guy except to make fun of his ineptitude, and you couldn’t figure out why Melman would keep showing up for the gig when he was only there to be laughed at. His every appearance in the early days was a high-wire act, with the audience not knowing quite what to make of this cranky, easily distracted and opaque old man. He couldn’t tell a joke — Christ, he could barely read his cue-cards — but the electricity between him and Letterman was astonishing. Routines would fall apart or turn into horrifying, cruel shouting matches and you didn’t know whether you wanted to laugh or cry but you certainly weren’t going to change the channel.

It turned out it was all a joke, but I never knew to what extent the joke was on Melman, DeForest, Letterman or the audience.

Nowadays, Letterman’s art of spinning comedy gold from the common man (Rupert Gee, Sirajul and Mujibar, et alia) is the norm on the show and everyone is in on the joke, but in the beginning, it was untested, even dangerous ground he was treading and the volatile Larry “Bud” Melman was his advance scout.

This is why I don’t watch TV news

“Is Wall Street worried about the Far Left hijacking the Democratic party?”

Listen carefully. The anchor is not making a statement, just asking a question. A question is not news, nor does it need to be supported by evidence. She could just as easily have begun the show by asking “Is Wall Street worried about clowns on Mars?”

The anchor raises the question, then turns to her colleagues and they talk about the question. For a few minutes they create the illusion that there is no other question worth thinking about. And soon the viewer starts to wonder, “gee, is this something that should concern me?”

Then they turn to an actual Wall Street analyst and ask the question again. “Is Wall Street worried about the Far Left hijacking the Democratic party?” and the actual Wall Street analyst looks baffled and says, basically, “WTF?” as though he just walked into the room.

So, no. Wall Street is not worried about the Far Left hijacking the Democratic party, Wall Street hasn’t even given a moment’s thought to the question. In fact, no one has worried about the Far Left hijacking the Democratic party except these people at Fox News, and of course, they are not worried about the Far Left hijacking the Democratic party, they would be thrilled if the Far Left hijacked the Democratic party. Because, in fact, the Far Left has not hijacked the Democratic party; this broadcast exists solely to raise the question in the minds of the vast majority of Americans who are currently sick to death of the way the country is currently being run.

Apparently Fox News does this sort of thing 24 hours a day.

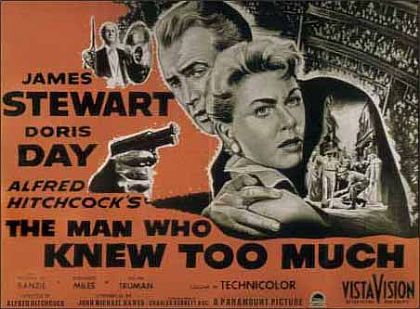

The (other) Man Who Knew Too Much

While it’s too much to say that the 1934 version of The Man Who Knew Too Much is “better” than the better-known 1956 version, there are areas where the original is a substantially better work.

The biggest tonal shift is the married couple. In 1956 they are middle-class Americans, Christian, uptight and oblivious to their surroundings, blundering around foreign countries at a loss. In 1934 they are wealthy, white-tie sophisticates, world-travelers who drink, trade bon mots with celebrities and joke about sleeping around. The shift makes the 1934 version both more giddy and more exotic — this couple seems to take the kidnapping of their child in stride, a simple problem to be solved with reserve, pluck and stiff upper lips, and there is plenty of time for banter and hijinx, and instead of recognizing the couple as people we know, we wonder what their private life must be like when they’re not dashing about Europe and participating in skeet-shooting competitions.

The Man Who Knew Too Much

The Man Who Knew Too Much could be one of the most influential movies in history, although it may not seem like it at first.

In the first 20 minutes alone, we see an American couple whose marriage is on the rocks trying to patch things up with a bus ride through Morrocco (which showed up later in Babel) an American doctor and his wife attending a medical conference in a foreign country getting tangled up in international intrigue (which showed up later in the echt-Hitchcockian Frantic) and a hectic chase through a crowded Morroccan marketplace (which showed up later in Raiders of the Lost Ark). For good measure, Jimmy Stewart also mentions that he was stationed in Casablanca during WWII. With movies like these flooding the culture it’s amazing that Americans ever leave home at all.

(And of course the whole “assassination at the concert” sequence was lifted for the 70s Hitchcock pastiche Foul Play.)

Friend

I stumbled across this piece today. It dates back to the early 90s. Even though I performed it fairly regularly, I have no memory of having written it. That’s how it goes sometimes.

She could never take care of herself. She was an accident waiting to happen, she was a bull in a china shop, she was dead but she wouldn’t lie down.

I used to say to her, forget it, this place, this time, it’s not for us, not for me and you. You walk down the street and what is this place, this place is a shambles, this place is a slaughterhouse, people a hundred years from now will look back on us and say “My God, how could they live like that?!”

Get Carter, Snatch

The alpha and omega of British gangster movies. The two could not be further apart in every way. Get Carter, from 1971, has a single protagonist, the structure of a revenge tragedy, an elegant, inexorable screenplay, gritty 70s realism, a palpable, Altmanesque sense of place, stunning, ferocious moments of brutality and ugliness, canny, closely-observed directing, and characters who are thinking, feeling human beings. Snatch has multiple protagonists, the structure of a screwball comedy, a ridiculously complicated screenplay bursting with incident and coincidence, flip 00s surrealism, action where even murder victims don’t seem to suffer, restless, anything-for-a-gag direction and a cast of screwy cartoon characters.

I dearly love both of them. When I can understand the accents, anyway.

My movie-going life crossed paths with Michael Caine during his “I’ll choose roles for the sunny locations” phase (beginning, I’d say, with The Swarm, continuing through Jaws: The Revenge and on to Dirty Rotten Scoundrels. This is Michael Caine during his “eminence for hire” era, and it’s easy to forget what an impressive, cold-eyed, nasty, mean little fucker he could be. He’s absolutely blood-chilling in Get Carter (and check him out in Mona Lisa as well, a dynamite script), a real cockney Samuel L. Jackson.

The script really helps. Everything is underplayed and unexplained. For the first half-hour, we’re not even sure who Caine is and what he’s doing. We know he’s some kind of London lowlife and we know he’s going to somebody’s funeral, but it isn’t until 25 minutes into the movie, when he suddenly picks up a fallen branch to knock a lookout man unconscious to we realize what kind of man we’re dealing with. We learn that the funeral was for his brother and that he didn’t die by accident, and we soon learn that Carter isn’t going to take his brother’s death in stride, and by the third act we almost feel sorry for the pornographers, gamblers and real-estate developers in his path, we cringe anticipating each savage remorseless, merciless encounter. We see him kick a car-door closed on a man’s head, grab another man by the genitals, throw yet another man off a seven-story car park. We see him drown a drugged woman, stab a man repeatedly in the gut and club another to death with a shotgun. We also get to see him engage in explicit phone sex (a cinematic first, I believe) while his landlady sits mere feet away.

Not that Carter is happy with himself, mind you. A good deal of his rage is directed inward as he knows that he, himself, is at least partly responsible for the death of his brother. He’s filled with turmoil and self-loathing and he plows through the underworld of Newcastle knowing that he’s never going to get back to London, he’s playing for keeps.

A lot of gangsters have passed into cinema history since Carter, but Snatch still manages to bristle with indelible portraits. The acting in Snatch is wonderful across the board, but two performances always stand out for me: Brad Pitt as the Irish traveler and Alan Ford as Brick Top, the gangster who feeds his enemies to his pigs. I’ve always enjoyed Pitt’s work, but his performance here is, I believe, without precedent. He’s game, lovable, fascinating and completely indecipherable, playing a character both utterly simple and yet utterly unknowable, and he positively inhabits the role, vanishes into it. It’s no star turn and no goof, he’s both playing the role straight and also performing it in the context of a comedy and you can’t take your eyes off him. This and Fight Club are his two best performances.

(I first saw Snatch in Paris [with Urbaniak and our wives, if you must know]: between the heavily-accented English and the French subtitles, we could almost make out what the actual plot of the movie was.)

When Alan Ford’s character first showed up, I first thought “Oh well, here’s another mean gang boss, I’ve seen this character a hundred times,” but Ford brings such a livid, seething intensity to the role that he’s breathtaking. I found myself actually scared of what he was going to do next, since there seemed to be no limit to his rage. Maybe it helped that I’d never seen Alan Ford’s work before (although he has a small role in Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels and has apparently done a lot of British television), I had no casting reference to fall back on (you know, the way we feel that it’s okay if Matt Damon kills someone in The Departed because we’ve seen him do it in The Talented Mr. Ripley but we freak when we see Henry Fonda kill someone in Once Upon a Time in the West because, damn it, he’s Henry Fonda, he’s not supposed to kill people!).

And, as different as the script for Snatch is from Get Carter‘s, I love the way the stories dovetail, I love tracing the plotlines from character to character and dive to dive, from madcap situation to madcap situation. If Richard Lester made gangster movies, they would probably be a lot like this. The scripts for this and two other Matthew Vaughn productions (Lock, Stock and Layer Cake) are, as far as I’m concerned, top-notch, intricate puzzle-boxes of narrative invention, Roman candles of collision and intrigue.