The Kid-pitching sketch

Schools have fund-raising dinners. If the school has some talented parents, one of the parents might get up and entertain.

My son Sam goes to a school in Los Angeles, so all of the parents are talented. And for their fund-raising dinners, instead of parents getting up and singing or doing a magic act, the parents all get together and make a short self-satirizing movie produced by, edited by, directed by and starring well-known industry professionals.

I’m still getting used to all this, but for the fund-raising dinner the other night the school asked me to write a short sketch to incorporate into their movie. I suggested a scene where some parents “pitch” their kid to the school as if he were a movie idea (since “pitch sketches” are the only sketches I’m capable of writing). It turned out pretty good, so I thought I’d share it with a wider audience.

Some Oscar thoughts

I don’t really know why, but the show seemed a whole lot more compelling this year than other years. It wasn’t the set, which was ugly, non-glamorous and bluntly utilitarian, and it wasn’t that I knew anyone up for an award.

Maybe it was, as Ellen Degeneres noted, the international flavor of the thing. It seemed like less of a clubhouse kind of affair than usual, and the people who stuck out weird were the ones who treated it as such. All kinds of people from all over the world and all kinds of backgrounds are making movies these days, and their movies are quickly becoming better, and in some cases more popular, than what Hollywood is producing.

Or maybe, taking a cue from casting Ellen Degeneresas host, it’s that the show business community is finally going back to saying “Oh yeah, that’s right, we’re liberal, and we actually don’t have to apologize for it. We forgot about that for a moment. We’re the cool kids, the Washington guys are the jerks.” The routine with Leonardo DiCaprio and Al Gore was funny to me because I honestly half-suspected that Gore really was going to take the moment to announce his candidacy (although I’m glad he did not, at least not at a showbiz event). The only thing that would have made Gore’s presence more gratifying was if someone had referred to him as the President of the United States.

Maybe it was the montages offered on the various themes. It’s always baffled me how, for decades, so much of the Oscar broadcast is handed over to dance numbers. Why are we watching (bad) dance during a program dedicated to the art of film? The montages made me remember what I was watching this for, that I am part of (or at least witness to) a long artistic tradition, that greatness is possible in all times, and that there’s nothing wrong or shameful about wanting to be a filmmaker. It made me sit up and, involuntarily, name aloud the movies I’d seen of those referenced, and feel a lack where there were ones I hadn’t seen. It made me want to see more movies, which is, to say the least, not the usual effect of the Oscar broadcast.

Maybe it was that I felt like the movies being honored were worth being honored, and that the winners deserved their awards. There wasn’t a single moment where I felt “so-and-so got screwed” or “this is all political” (with the possible exception of Eddie Murphy losing to Alan Arkin). I preferred Pan’s Labyrinth to The Lives of Others, but I wouldn’t say that the latter movie, a gripping political drama, didn’t deserve to win. In fact, I’ll say the opposite: I’m glad that The Lives of Others won so that maybe people will go see it this weekend. I made a joke in an earlier post about how “West Bank Story” would win because it’s about Israel, but when I saw the actual clip I thought “Wow, that’s a great idea for a movie, I want to see that.”

Maybe it was my daughter Kit (4), who got caught up in the dresses, particularly the red number Jennifer Hudson wore during the Dreamgirls medley. “She’s bee-yoo-tee-full,” cooed Kit. Then when Beyonce came on, she said “Who’s that?” When I told her who was who, she thought for a moment and declared that both were “bee-yoo-tee-full,” but Jennifer Hudson was the most “bee-yoo-tee-full.”

Or maybe it was the bag of gourmet caramel corn that ate during the show. What the hell do they put in that stuff that makes it so you can’t stop eating it?

CONFIDENTIAL TO

:

I know you have no plan of moving to LA, but if you do, you could probably make a living off of people mistaking you for Jackie Earle Haley. I’m not saying, I’m just saying.

The Spider-Man sketch

Spider-Man by Sam, age 3. This was his first-ever representational drawing.

In honor of ![]() urbaniak‘s appearance today at the NYCC (with jacksonpublick , Doc Hammer and my good friend Mr. Steven Rattazzi) I here present the famous “Spider-Man” sketch, which James and I performed a couple of years ago at a similar event at MoCCA.

urbaniak‘s appearance today at the NYCC (with jacksonpublick , Doc Hammer and my good friend Mr. Steven Rattazzi) I here present the famous “Spider-Man” sketch, which James and I performed a couple of years ago at a similar event at MoCCA.

UPDATE: as one can see, I have finally figured out the “cut” function. Thank you ghostgecko.

The Spider-Man Sketch

The Matrix trilogy

In my Hollywood travels, I am often asked to adapt this or that popular work of fantasy. When doing this, what I need to do first is remove the metaphor and see if the story still works.

For instance:

A few years back, they asked me to adapt Osamu Tezuka’s Astroboy for the American movie screen. The story of Astroboy is: a brilliant scientist’s son dies in a car wreck and so the brilliant scientist spends all his company’s money and resources to build a robot replica of the son. The robot looks and acts like his little boy but, much to the scientist’s chagrin, does not grow. Well of course it doesn’t grow, it’s a robot. So the scientist, filled with rage and self-hatred (and not feeling quite so brilliant any more), sells the robot to a robot circus.

Now then: we don’t have little-boy robots in this world, so I had to think what Astroboy was a metaphor for.

What I came up with is this: a man has a son, and the son dies, so the man has another son, and is disappointed and outraged that the second son does not turn out to be a good replacement for the first son. So he turns his back on the second son, unable to love him.

What would this spurned second son do? He doesn’t know what he has done to incur his father’s disappointment. He doesn’t even know that there was a first son. The second son, it occurred to me, would do everything in his power in order to gain the thing that the first son got just by being born: his father’s love. In the case of a real-life little boy, that would mean working hard, overcoming grief and hardship in order to become the best he could possibly be. In the case of Astroboy, it would have to mean nothing less than saving the world from, I don’t know, a mad scientist’s evil robot or something. Astroboy would have to become the most powerful entity on the planet, all in the hopes of gaining his father’s love.

Anyway, that’s how I got the job writing the Astroboy screenplay. (That movie, the reader will surely be aware, didn’t get made. Such is life.)

The Matrix has a wonderful, daring, innovative screenplay, a killer hook and a terrific metaphor. (It also has probably the best tag-line I’ve ever heard in a movie trailer: Lawrence Fishburne intoning “Unfortunately, I cannot tell you what the Matrix is; you have to experience it for yourself.”)

Neo is convinced that something is not right with this world. That “something not right” turns out to be (spoiler alert) that the world we know is actually a vast computer simulation, created in order to distract us from the fact that we are actually living in tubs of pink goo and powering the machines that actually rule the world.

That’s the killer hook. And you know what? I’m going to bet that it turns out that, in reality, the world we know is not actually a vast computer simulation, and that we do not actually live in tubs of pink goo. The Matrix, then, is the metaphor.

A metaphor for what? Well, you know, the corporate machine, that all-consuming, media-driven monster that has us surrounded, gets us from every possible angle and keeps us so amused, confused and abused that we willingly give our lives to it. That thing. How shall we behave in this world? How can we balance our desire to be free with our need to be a part of the world? Can we “free our minds” from this pervasive corporate monster? What happens if we “unplug” from the world? What would we find “out there?” Will we be happier? These are the real, everyday, pertinent questions The Matrix had to offer its audience.

(This is the same metaphor used in the Alien movies, the corporate culture that would rather invite a rapacious, heartless monster intothe world rather than pass up an opportunity for profit.)

The good folks who made The Matrix, unsurprisingly, found themselves with a substantial hit on their hands and decided to make two more movies based in the same world back to back. Why not? The world created in The Matrix is fascinating and well-worth the time spent investigating it. The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions, while not as fluid dramatically as the first movie, are still visually stunning and philosophically complex. The action sequences are nothing less than stupefying and the dense intellectual underpinnings are, well, they’re dense enough that this viewer has had to watch the movies three times in order to begin to grasp just what the hell some of the characters are talking about.

And there’s where I think the problem lies, why the second two movies fail to engage on the same level as the first. The second two movies take place in a world so fascinating that the fimmakers decided to abandon their metaphor, and make a movie about the imaginary world. Or rather, the filmmakers’ ambitions are so vast that they decided (or planned all along) to expand their metaphor of late-corporate media culture to include philosophical notions of the nature of human life so vast and complex that they appear to be all-but opaque, and certainly uncinematic. To get around this problem, they include action sequences of mind-boggling immensity and plot twists startling in their ordinariness (the bumbling recruit who saves the day, the hot-shot pilot who bucks staggering odds to get her ship to dock, the Mexican standoff with the effete, sneering Frenchman). The action sequences demand to be seen again and again, and in between one can begin to make sense of long, motionless scenes about “systemic anomalies.”

This is the same problem I have with Dune or Lord of the Rings — I can’t locate the metaphor in these works. I know other people, many other people apparently, do not have this problem. But as for me, I’m not interested in the vast complexity of an imaginary world, I’m interested in this world. I attend a drama so that I might better understand how to live my life; what do the second two Matrix movies offer in this regard?

DC vs DCU

Tonight’s bedtime conversation with Sam (5).

SAM. Is tomorrow a school day?

DAD. No. It’s Presidents’ Day. Do you know who the Presidents are?

SAM. Yes.

DAD. Yeah? Can you name one? Who was a President?

SAM. (patiently, as though to a dull toddler) George Washington.

DAD. Do you know what the President does?

This Sam is less clear on. Which is just as well at this embarrassing point in our nation’s history.

I start to say that if the United States is the DC Universe, you could look at George Washington as Superman, but then I realize that if I say that, the next question will be “Then who is Batman?” and I don’t have a clear answer for that.

Clearly, George Washington is Superman. He was the first, arguably the most important, debatably the best, and most importantly the “original.” But then, indeed, who is Batman? Is it Adams, contemporary of Washington and close second in defining the young nation’s ethos? Or is it, say, Lincoln, the most beloved of the presidents, the tall, dark, brooding loner president, the tortured insomniac, haunted by the deaths of his loved ones, the one who broke the rules for the sake of the greater good?

Does that make Wonder Woman Thomas Jefferson, the warrior for peace, architect of our most precious freedoms? Or is she more like Franklin Roosevelt in that regard, giving our enemies a bitter fight while generously giving our poorest and weakest a fighting chance of their own? That would make Truman Green Lantern, saving the world with his magical do-anything world-saving device.

And who would be an analog for colorless chair-warmers like Millard Fillmore and Chester Arthur? Are these men Booster Gold and Blue Beetle? Clearly Rorshach is Richard Nixon, Alan Moore practically begs us to see the parallels, but what of Kennedy, Nixon’s shining twin? Is that Ozymandius, or is he a simpler man, a purer spirit, someone like Captain Marvel? Or is he Superboy and his “best and brightest” cabinet the Legion of Superheroes in the 31st century?

And how to categorize corrupt, incompetent disasters like Grant, Harding, Hoover and Bush II? Is Reagan Plastic Man, effortlessly escaping ceaseless attack with a smile and a quip? And what about Johnson, weak on foreign policy but a genius in the domestic realm, who is that? Or William Henry Harrison, who caught pneumonia during his inaugural parade and died a month later? Or Grover Cleveland, who served, left office, then came back and served again?

Or perhaps the metaphor is imprecise, perhaps the US presidency is unlike the DCU after all — perhaps it’s more like the X-Men, where weak individuals are granted extraordinary powers and yet are still hampered by their combative attitudes toward each other and their under-developed social skills. In the X-Men you have heroes who might not turn out to be heroes after all. And vice versa.

Or maybe we’re looking in the wrong direction, perhaps the US presidents aren’t the “good guys” at all. While Bush II has so far shunned the metal mask and hooded cloak of Dr. Doom, he has certainly succeeded in turning the US into his own private Latveria. And any given Republican of the 20th century can lay claim to being the Lex Luthor of the bunch, brimming with brilliant, short-sighted schemes to make himself rich while destroying other people’s lives and property.

And, if they were given the choice, is there any serious doubt as to whether Americans would elect a comic-book character over a living, breathing human being?

My Supergirl

As a comics fan and the father of a young Supergirl-loving daughter, I have been following the recent controversy surrounding the recent appearance of Supergirl.

Recently, a meme has sprung up in response, wherein various artists have contributed their concepts toward a new vision of Kara, the last cousin of Krypton. Above is my effort.

I do not claim supremacy in the sequential arts.

You may click to see it larger.

UPDATE: Unable to leave poor enough alone, I have fiddled with the shading to make her a tad more realistically lit.

Oh, those paranoid delusions: Harvey, They Might Be Giants, Man of La Mancha

Three movies about men with delusions. In Harvey, James Stewart believes he’s followed around by a tall white rabbit, in They Might Be Giants George C. Scott believes he is Sherlock Holmes, in Man of La Mancha Peter O’Toole believes he’s a good actor Don Quixote.

In each of these movies, the families of the men seek to have them committed. In each of these movies, the filmmakers would like us to side with the crazy guy. Insanity is so cute in Hollywood. It’s not destructive or terrifying or heart-rending, it’s sweet and harmless and adorable, and if we look upon these men as anything other than inspirational, isn’t it really we who are the crazy ones?

Call me mean-spirited, but by the end of Harvey I wanted to strap James Stewart down to a table and give him electro-shock therapy. That would wipe that sweet, silly grin off his face. Stewart was nominated for an Oscar for this cloying, sentimental performance (big surprise) (and later repeated it for a 1972 TV version), but I’m glad I saw him first in Vertigo and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.

SPOILER ALERT: It turns out the rabbit is real.

They Might Be Giants is the most enjoyable, at least for the first half. George C. Scott actually makes a pretty good Holmes, acerbic, arrogant, full of himself, and the sight of him wandering around a gritty, 1970 New York is startling. The movie also gets points for inspiring the name of my favorite currently-working American band. It also gets points for featuring a fine New York cast, including Jack Gilford as a librarian, F. Murray Abraham as a theater usher, Eugene Roche as a policeman, M. Emmet Walsh as a garbageman and James Tolkan as some guy. Alas, the movie is about a crazy guy and the analyst trying to cure him, so by the mid-point of the movie the analyst starts believing in him, and so does everyone else he’s met, and the narrative quickly gets retarded real fast. By the final reel it spirals completely out of control; the analyst falls in love with her patient, the performances turn disastrously sentimental and the narrative even clumsily attempts to enter the cosmic.

Man of La Mancha is just awful, a stagebound chore of a movie. A film of a musical of a novel (that would be Don Quixote), it fails on all levels. Released in 1972, late in the Hollywood Musical run, it stages its numbers almost apologetically, as though embarrassed to include them at all. The actors shuffle around the soundstage, “talking” the lyrics and half-heartedly moving to the music without actually performing any choreography. Several conceptual devices, such as mixing locations with soundstages and filming fantasy with “gritty 70s realism” camera work gut whatever effect the stage musical was after. Peter O’Toole is okay in a stylized way as Don Quixote but his scenes as Cervantes are unwatchably, depressingly loud, hammy and emphatic in the “Great British Actor” mode (cf Richard Burton, Laurence Oliver).

What is it about clinical insanity that Hollywood feels such a need to defend? They want us to love these kooky misfits, they want us to hold them up for high regard, as they see the world more clearly than we do.

Can someone please direct me to a movie that portrays insanity as something other than a cute, harmless eccentricity? Certainly, somewhere in cinematic history, insanity has been portrayed somewhere between the two extremes of Arsenic and Old Lace and Psycho.

They Might Be Giants, in its own way, is also an adaptation of Don Quixote and takes it’s title from Quixote’s response to the windmills: yes, they look like windmills, but they might be giants. This makes it a perfect name for the band, and for a movie about a guy who thinks he’s Sherlock Holmes.

And how perfect is it that Pedro Almodovar (pictured above) is literally a Man of La Mancha?

All three of these movies were based on stage plays, and all of them show it to one degree or another. This is another good reason to abandon theater as an art form.

The Jaws of Love

(Another piece from my monologue days.)

I’m a man, I’m an idiot, it follows. I’m a man, I’m an idiot.

I’m human, that’s the problem. I’m human, I’m an idiot, it follows. I’m human, I’m an idiot. You can’t teach me anything, I won’t learn, I’ll never learn, I can’t learn, I’m an idiot, I’m trapped and you can’t teach me anything.

You ever look into someone’s eyes and been reduced to the size of a pin? A pin, a pinpoint of light, been reduced to a pinpoint of light? You ever see someone toss their hair back and it made you fall silent? You could be talking to someone — “Oh, yes, the third episode with the dwarf was the best” — and they do this –

[imitation of hair-flip]

— and you fall silent. Because, you know why? Because Something Important Has Happened. Or, or, you’re talking to this person, this person, this certain person who makes your heart want to get in your car and turn on some rockabilly and drive somewhere, and you’re hanging on every word this person says, and then this person says something like —

…”that would be nice”…

— and it dislodges this rock, somewhere in the deep stream of your subconscious this rock is dislodged, and you find yourself thinking about things you haven’t thought about in years. Am I ugly? Do I need some mints? How come I never read any Shelley? Jesus, do I weigh that much? This rock is dislodged, it sets off an avalanche in your head that wipes out everything else in your brain.

And you fall silent. It’s like you’re in church, it’s like you’re worshipping. Because you are in church. You are worshipping. You are having a religious experience.

Why? Why this person? Who is this person? What do you know about this person? Doesn’t this person have terrible taste in music? Doesn’t this person smoke? Isn’t this person ten years older than you? Isn’t this person not attracted to your sex? Doesn’t this person think you’re an insignificant blot on an otherwise charming landscape? Isn’t this person the rudest, clumsiest, most incorrigibly maddeningly frustratingly difficult person you’ve ever met in your life? Well? Then why? Why are you talking to this person? What is the point? Why are you bothering? Why do I find myself in this exact same position right now?!

Because —

[gesture to body]

— this, you see, this, you know what this is, this is flesh. It’s all I’ve got. It’s all they gave me. I didn’t get a book of rules. I didn’t get a wise old mind that could see into the future and tell me that these feelings would die, that lovemaking would become rote and tiresome, that I would lose interest, that we would get into fights over things like, like white-out!

I didn’t get that mind, my mind doesn’t say those things, my mind says things like YES! My mind says things like NOW! My mind says things like DANCE, like, like, KISS, like, like, GRAB THIS PERSON NOW! GRAB THIS PERSON NOW!

I don’t know what it is, of course I don’t know what it is. It’s not meant to be known, not by us, not by me, not in this life, not in this world. It’s a feeling, that’s all, it’s a feeling, you know it when you feel it, it’s like these jaws snapping shut on you, on me, like they’ve shut on me, and I’m trapped, because, because, I’m a man, I’m an idiot, it follows, like I said, these jaws are as big as the fucking universe, and they’ll chew me up and spit me out, and I’ll never learn, I’m trapped, I’m an idiot, and I’m trapped in the jaws of love.

Happy Almost Valentine’s Day

For your romantic inspiration, some tender moments from Justice League.

This is, of course, the real reason why I watch the shows of the DC Animated Universe — it’s all the hot, hot man/woman, woman/alien, man/mythological figure, man/scientific experiment, man/winged alien, woman/alien, psychopath/psychopath, woman/scientific experiment, alien/robot, martian/martian, man/psychopath, mythological figure/martian, alien/winged alien, woman/mythological figure love going on.

As my son Sam (5) exclaimed after one episode of Justice League: “Everybody on this show is in love! I thought this show was supposed to be serious!”

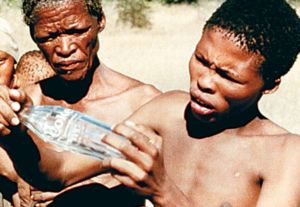

The Gods Must Be Crazy

It is not the goal of this journal to heap scorn, so I will keep this brief.

In the early 1980s, the movie The Gods Must Be Crazy was a surprise worldwide smash hit.

Why? Well, it has a delicious premise — a Coke bottle falls out of the sky (tossed from a passing airplane) and is found by a tribe of Bushmen in the Kalahari desert. The bottle, being unique and beautiful, leads to jealousy and conflicts in the tribe. So the leader of the tribe, Xi, decides to travel to “the end of the Earth” to return this gift to the Gods who, Xi believes, dropped it. As he travels to the end of the Earth, he encounters civilization, and civilization is shown to be ugly, cruel and insane compared to the simple, edenic life of Xi’s blessed, carefree people.

In addition to the premise, it showed, or claimed to show, the world something it had never seen or heard before — “real” Bushmen (that is, non-actors) and their click-consonant language.

People were amazed that, in the go-go 1980s, there were still “savages” living in total innocence, peaceful, child-like people whose world could be turned topsy-turvy by an object as innocuous as a Coke bottle. The movie’s fake National Geographic-documentary format helps reinforce this notion.

Wikipedia informs us:

“While a large Western white audience found the films funny, there was some considerable debate about its racial politics. The portrayal of Xi (particularly in the first film) as the naive innocent incapable of understanding the ways of the “gods” was viewed by some as patronising and insulting.”

Count me in!

Now, I’m a storyteller by trade, so I understand the comedic potential in viewing civilization through the eyes of a naif. It worked in Splash, it worked in Being There, it worked in Forrest Gump, it worked in Crocodile Dundee. But those movies weren’t pretending to show us “real” naifs; they employed professional actors to pretend to be innocent. The Gods Must Be Crazy got its international frisson by telling us that its protagonist was a real innocent, the comedic equivalent of a snuff film. “Watch as a genuine innocent gets humiliated and corrupted by the evil, evil West!”

What is “patronising and insulting” about the filmmaker’s treatment of the Bushmen in general and Xi in specific? The narrator tells us, many times, that conflict is unheard of in the Bushman world, that they don’t have words for “fight” or “punishment” or “war.” This may or may not be true; the writer (who is also the director, producer, cameraman and editor) presents it not for its factual basis but for its potential for comedic juxtaposition. The Bushmen were living in Eden and then this wicked, wicked Coke bottle fell out of the sky and brought conflict to them.

Now, I’m trying to think of something more insulting, more patronising one could say about a people than that they have no conflict, and no notion of conflict in their lives, and it’s not coming to me. To call such people “childlike” is an insult to children, whose lives positively boil over with conflict. To call such people more “natural” is an insult to Nature, which is defined as remorseless, brutal and ceaselessly ridden with conflict.

The DVD of this movie comes with a 2003 documentary, wherin a vidographer travels to Africa to find the tribe of N!xau (the actor, or non-actor, playing Xi) to find out for himself how much of The Gods Must Be Crazy‘s presentation of the Bushmen’s world is accurate. I could have saved him the time, because the falsehood of the movie’s premise is right there on the screen; the Bushmen of the movie are flabbergasted by the sight of a Coke bottle, but not of a film crew, recording their fictional actions. This is the height of insult in this loathsome movie — the filmmaker goes to the Kalahari, explains to the tribespeople who he is and what he’s trying to accomplish, puts the “genuine” tribespeople in costumes (or lack of them), constructs a fictional world they live in, asks them to perform comedic pantomimes illustrating a dramatic situation (“now, pretend you’ve never seen a Coke bottle before — it’ll be comedy gold!”), gets convincing, “authentic” performances from them, records it all on film, then assembles the finished movie to convince people that they are watching genuine innocents cavorting in an unspoiled Eden. And the white people of the Western world eat it up.

The insult to Xi and his people is compounded as Xi gains his education in civilization. He is put through hell in the form of the local justice system, with arrest, convicition and imprisonment for a crime he does not understand, and yet he remains, of course, thoroughly innocent, bewildered by what is happening to him. So apparently he is not only innocent, he is stupid and unconcerned for his own welfare. Not only that, he goes through his entire ordeal and apparently never sees another Coke bottle, or anything resembling such, never puts together that the magical, evil item that has beset his existence is, in fact, a common item of little consequence. That would make him a very stupid innocent indeed, but that is how the filmmaker presents him.

None of this would matter if the movie happened to also be a comedic gem, but it is not. It has a terrible script, wherin Xi’s quest to venture to the end of the earth is quickly shunted aside for unrelated storylines concerning a bumbling terrorist group and a bumbling researcher’s attempts to woo a pretty young schoolteacher. Sooner or later, all the storylines meet up, and wouldn’t you know it, Xi’s naivety and savage ways come in useful for the white people in the attainment their goals. In true western film tradition, and just so you know where the filmmaker’s heart truly lies, the white couple end up with most of the screen time and are given top billing.

The comedy is exceptionally broad and grating, and most of it operates at the level of an episode of Benny Hill, complete with copius undercranking and music-hall piano.

The technical aspects are abysmal; the image is washed-out, grainy and flat, and most of the sound seems to have been dubbed, badly, by amateurs.