Sam’s corner

Martian Manhunter, his wife and child, drawn by Sam (5), from looking at his Justice League action figures.

“I’m trying to really look!” he exclaimed in the middle of his work.

The Joy of Lex

SAM (age 3): Who is that?

DAD: That’s Lex Luthor.

SAM: Is he the bad guy?

DAD: He is the bad guy.

SAM: Then why isn’t Superman fighting him?

Lex Luthor is the greatest, and most difficult to define, villain in the comics universe.

In 1940, when he was just Luthor, he was a mad scientist, much like many other mad scientists of the day. He created amazing machines and planned to use them to take over the world. There was a lot of that going around in the 1940s, when there were plenty of scientists, mad or not, and they very much did take over the world. People understandably were nervous about technology and its ability to shift the balance of power in the world.

The idea was, if Superman was Strong and Good, then his nemesis must be Smart and Evil. Lex created Superman robots, Superman clones, anti-Superman rays, all matter of ingenious devices for no other purpose but to destroy Superman. (In one of the many delicious plot twists of the the stunning Red Son, Superman comes to the realization that, if not for his existence, Luthor would have been able to use his vast intellect to solve every problem humanity faces — he would have been the greatest leader in human history.)

In the 1980s, John Byrne re-created Lex as a businessman, a tycoon, the head of Lexcorp. Again, it fit with the times — the villains of the 1980s were men like Gordon Gekko, bloodthirsty capitalists who cared nothing for people, lives or even businesses — they yearned only for money. Again, it’s a good foil for Superman because it’s natural strength vs. economic strength.

In the 2000s, Lex became President of the United States. One has to wonder what took him so long.

On Superman: The Animated Series and Justice League, they put all of these visions together to arrive at the fullest, most complex version of Luthor yet. This Luthor is hugely wealthy, employs millions of people, controls the economy of Metropolis, runs for president and, when the mood strikes him, finds time to tryto destroy Superman.

Maybe that’s what makes him interesting: he actually has other things to do besides destroy Superman.

The conversation quoted at the top of this entry occurred while Sam and I were watching one of the first episodes of Superman: TAS. They were taking great care to show who Lex is, how his business is constructed, how he’s an important and vital member of the community, not some penny-ante thug with a crazy plan — all of which completely baffled my (then) 3-year-old son. He couldn’t understand Lex, Lex’s legitimate business, he couldn’t understand that not even Superman can just fly into Luthor’s penthouse suite and punch the guy who employs more people than anyone in Metropolis and also controls municipal government. How do I explain to my son that you can’t punch someone merely because they’ve risked the lives of millions of people in their pursuit for power, that, in fact, in our country men are greatly rewarded for that kind of behavior?

(Note: I began this piece before I was aware of the president’s speech on Iraq tonight.)

When I was a kid I kept hearing about the Mafia and how there were these terrible criminals running organized crime in America, and everyone knew who they were but they were still running around free. I just kept wondering “If everyone knows who they are, why can’t the police just walk in and arrest them?” Like those Mafiosos, Lex is too smart to get caught in any of his nefarious schemes, and, more often than not, Lex’s schemes for power-grabs backfire on him in ways that have nothing to do with Superman’s interference. The Lex Luthor of Superman: TAS and Justice League is no two-dimensional bad-guy. The Joker is a psychopath in a garish costume, Sinestro is an evil guy with a magic ring, Mr. Freeze is a guy with a gun; you can see those guys coming a mile away. But Lex? If you foil a Lex Luthor scheme, chances are it’s because he wanted you to foil it because it somehow serves his greater plan. Only the Lex Luthor of Justice League could devise a presidential bid that’s actually a distraction to divert attention from his REAL plan.

As the earlier Luthors served their times, this Lex serves ours. A brilliant scientist, who is also the head of a multinational corporation and also president of the United States? The only thing that sounds out of place there is that we would have a brilliant man as president. Just as we once felt suspicious about science and capitalism, we now as a nation are starting to get the same sense of ill-ease about our corporate-owned political leaders. Despite their rhetoric, we get the feeling that maybe they don’t have the best interests of us, or the Earth, in mind when they make their decisions.

(The climax of Season 1 of Justice League Unlimited features a jaw-dropping team-up of Luthor and Brainiac that plays to both of their strengths — Brainiac wishes to destroy the universe (yes, the universe) and Lex seeks ultimate power — and in this case is offered the chance for godhood. The — ahem — “surprise reveal” of the team-up is one of the most disturbing things I’ve ever seen in children’s programming.)

For some reason, for the live-action movies, Superman, Superman II, Superman IV and Superman Returns, Warner Bros neglected every possible valid aspect of Lex Luthor. In these movies, Lex is not a scientist, a businessman or a politician. He’s a fop, an opportunist and a jerk. Far from being a genius, he’s not even bright. His plans are ridiculous, obtuse and fatally short-sighted. He is, in fact, the opposite of a genius — he is a man who keeps saying he is a genius. He’s a blowhard and a poser, vain and obvious, surrounding himself with morons and sycophants to make himself feel smarter. The Lex of the animated show doesn’t have a two-bit hussy and a slobbering idiot in a straw boater for a staff, he seeks out and hires the best and the brightest people in the world (a strategy that sometimes backfires for him when they get wise to his plans for universal domination). What does it say if I’m watching the $200-million-plus Superman Returns and I keep wishing I was watching a cartoon instead?

Christ, in Superman they wouldn’t even present him as bald! It seems obvious to me that the screenwriters of the first Superman movie never even bothered to read one of the comics they were supposedly adapting. I can just see the first meeting between Mario Puzo and Alexander Salkind:

M. So, Superman, blue suit, right?

A. Yes, and the red cape.

M. Super-strong or something, right?

A. Good-looking. The ladies like him.

M. Right. And who does he fight?

A. Um, let me — Ilya!

I. (from the other room) Yes?

A. Who does Superman fight?

I. Lex Luthor.

A. Lex Luthor.

M. (writing it down) L-e-x, L-u-t-h-e-r.

A. That should be an “o” in Luthor.

M. What?

A. Nothing.

M. So this Luthor guy, what’s he like?

A. He — Ilya?

I. WHAT!

A. Come in here so I don’t have to shout!

(Ilya comes in)

I. What.

A. Tell us what Luthor is like.

I. He’s a, a guy.

A. Yes?

I. And he hatches evil plots.

M. Mm. Yes?

(pause)

I. What.

M. That’s it?

I. And he’s bald.

(M winces)

M. That’s going to be a tough sell. They’re never going to get Hackman to shave his head. Does he have to be bald?

Superfriends vs. Challenge of the Superfriends

Pick hit: Superfriends (but not with Wendy, Marvin and WonderDog). Must to Avoid: Challenge of the Superfriends.Having never seen either of these shows before, I was under the impression that they were actually different seasons of the same show. This is not so. Superfriends, which is a masterpiece, dates from 1973 (or maybe not — see comments). Challenge of the Superfriends, which sucks, is from 1978.

Both shows are good illustrations of why Justice League is better — mainly in the character department. On Superfriends all the superheroes not only talk the same way, they all have the same personality — genial, wisecracking, earnest and stolid. If nothing else, Justice League discovered that by giving superheroes different personalities you could create conflict, which would result in narrative interest. In short, shows like Superfriends are where children get the notion that Green Lantern and Aquaman are lame. Justice League, for better or worse, has, by giving them personalities, somehow made them cool again.

Allow me to discuss some of the key differences between the two shows.

Superfriends (1973? 1979? see comments)

The Superfriends are:

Superman

Batman and Robin

Wonder Woman

Aquaman

The Wonder Twins (and the Space Monkey, Gleek)

They hang out at the Hall of Justice, which is on Earth, rather than in the Watchtower, which is in the unreachable confines of space. There is an abstract sculpture outside the Hall of Justice so we know it’s official.(I wonder what city the Hall of Justice is located in. What is the Superfriends’ deal with the city officials? What city would allow them to put a huge building, complete with “public space,” in the middle of town? Why not just paint a gigantic target on the city?)

Occasionally, someone in Superfriends refers to the Justice League (as in, “the Justice League computer indicates that the electrical disturbances are being caused by the Brain Creatures on Mars”), but the Superfriends do not seem to be the Justice League. Maybe the Justice League has broken up, maybe they’re on hiatus.

Oftentimes, all the superheroes are gone, leaving the Hall of Justice in the hands of the Wonder Twins and their Space Monkey. There is no staff, no security, just two teenaged aliens and a space-monkey.

The Wonder Twins, it should be noted, do not have “super powers.” They have unique powers, but they do not possess super strength or high intelligence. To say the least. And Gleek tends to drag them down, causing mischief and fouling the computer. Personally, I don’t see why they don’t board the Space Monkey in a Monkey Kennel when they travel on a dangerous mission.

The Superfriends mostly fight creatures from outer space and other extraordinary cataclysms.

The Superfriends are generally well-challenged by the disasters hurled at them. Superman and Wonder Woman are the only ones with super powers, and they are often turned to evil by whatever they’re fighting that week, leaving the comparatively mortal Batman, Robin and Aquaman to figure out a solution.

Aquaman is particularly useless in this regard. He’s a good-looking chap, but his ability to communicate with sea creatures is a little beside the point when in space, or on the surface of an alien planet.

I’m not sure why the Superfriends don’t suggest, in a nice way, that Aquaman sit out the challenges that await them in deep space. He’s always good company, but when one sees him in a space helmet, shifting his weight uncomfortably as it occurs to him that he’s utterly dead weight on a desert planet overrun by robot cowboy outlaws, his discomfort and embarrassment is palpable.

The show, which only lasted 16 episodes, explodes with goofy wit, imagination and charm, and is full of perilous, exciting, peculiar and fanciful situations. In one episode, the Superfriends must battle at least a dozen different creatures, from giant eels to sentient tar-men, at the Earth’s core. In another episode, Dracula comes to life after a 100-year slumber and, using an irridescent pink powder, turns an airplane full of tourists into vampires. Before long, Superman himself is turned into a vampire and leads armies of zombie vampires through the Transylvanian Alps to Vienna, where Batman must cure him with a gas retrieved from a cave in the Andes. In my favorite episode, Aquaman is turned into a giant land-dwelling mutant shark and Superman and Wonder Woman are shunk down Fantastic Voyage-style to cure him while he rampages through the city.

Challenge of the Superfriends

In Challenge of the Superfriends, the Superfriends are:

Superman

Batman and Robin

Wonder Woman

Green Lantern

Aquaman

The Flash

Hawkman

and a couple of others, Black Vulcan I think and some Indian guy.

In Challenge of the Superfriends, the Superfriends fight only the Legion of Doom. This is plenty of work, but it gets old fast.

The Legion of Doom consists of:Lex Luthor

The Joker

The Riddler

Cheetah

Sinestro

Solomon Grundy

Black Manta

Bizarro

Gorilla Grodd

Captain Cold

Toyman

and about fifteen other also-rans, some of which are redundant and puzzling. Why, for instance, Lex Luthor thought he needed a zombie strongman on his team is a mystery. The hyper-intelligent gorilla I understand, but some of the others defy comprehension.

The Legion of Doom, according to the opening titles, has a very vague, broad mission statement: the conquest of the universe. “Conquest of the Universe” apparently includes everything from conquering alien worlds to overtaking secret gorilla cities in Africa.

Why, for instance, does the Clock King need to build a giant clock made out of ice? How will this further the goal of “Conquest of the Universe?” The logic is known only to the Legion of Doom. Lex Luthor is a criminal genius, so there must be a reason that lies beyond my comprehension, but still.

Because there are literally dozens of characters to keep track of, there is always a ton of exposition in each 22-minute episode. You can actually see the animated characters sigh and get impatient with the things they need to do in order to include everyone.

Let’s face it, there is no earthly catastrophe that cannot be solved by the combined superpowers of the Superfriends. But because they all must be included in the solution, Wonder Woman will become stupid and incompetent at crucial moments, or Batman and Robin will suddenly be stumped for a solution so that Black Vulcan (whoever he is) can have his moment in the sun. It’s the democratic ideal at its absolute worst.

For some reason, this democratic ideal extends to the Legion of Doom as well as the Superfriends. You would think that if the Superfriends are a democracy then the Legion of Doom would be a totalitarian dictatorship, but no. A typical Legion meeting will begin with Lex Luthor (who is the undisputed leader) saying “okay, Riddler, what is your agenda for this week?” And maybe the Riddler has a plan, maybe not. Maybe his plan involves conquest of the universe, maybe it just involves a jewel theft or the construction of a robot dinosaur. Lex, for some reason, in spite of the fact that he’s a criminal mastermind, gives all ideas equal weight no matter how expensive or improbable they sound. He might hear a plan from Solomon Grundy that involves little more than Solomon Grundy wishing to destroy something, but all the resources of the Legion will be placed behind his plan. Because, after all, it’s his turn. It doesn’t matter if the Joker has a foolproof plan to crash the Pentagon’s computer system, he had his turn last week and now we’re going to pay attention to the zombie strongman.

At the end of every episode, the Superfriends will have the Legion of Doom cornered and caged. And at the end of every episode, Lex Luthor will pull a device out of his pocket that will, as if by magic, allow the Legion of Doom to escape again.

Strangely, the Superfriends, in spite of their combined might, are always caught short by this ruse, and must always stand frustrated and impotent as the Legion of Doom gets away again.

The squandering of resources on both sides is staggering. Lex Luthor, who seems to have the mental capacity to achieve anything in the world, consistently puts his energy and resources into plans that sound like utter wastes of time. Conversely, the Superfriends have to spend huge amounts of resources cleaning up after these absurd, wasteful spectacles every week.

In this way, Challenge of the Superfriends is the perfect metaphor for the Cold War.

Challenge of the Superfriends, like Superfriends, lasted 16 episodes. Unlike Superfriends, it is dreadful.UPDATE: It appears that the show I identify as 1973’s Superfriends is actually 1979’s The World’s Greatest Superfriends, although it is not identified as such on the DVD box. I strive for the utmost in accuracy in my reportage, unlike some OTHER bloggers I could name, and deeply regret the error. I humbly apologize for any distress this error may have caused anyone.

Justice League part 3 — the Martian Manhunter

left: the Man of Steel. right: creepy green loser.

Superman: super-strength, super hearing, super breath. Telescopic sight, X-ray vision, heat vision. Can fly and travel at super speeds.

Martian Manhunter: super-strength, super breath, heat vision, can fly. In addition, can read minds, communicate with spirits, walk through walls, change his shape.

Superman: the last surviving member of his race, the only living Kryptonian (except for Supergirl, Krypto, Streaky the Supercat, Comet the Superhorse, Beppo the Supermonkey and the entire city of Kandor — Jesus, did anybody but Superman’s parents die when Krypton blew up?). An alien on Earth, doomed to a life of loneliness, except for Lois Lane and the billions of people who adore him.

Martian Manhunter: the last surviving member of his race, the only living Martian. An alien on Earth, doomed to a life of loneliness.

Superman: invulnerable, except to an ultra-rare metal.

Martian Manhunter: invulnerable, except to not-rare-at-all fire.

On paper, Martian Manhunter is the more powerful figure, much more powerful than Superman and possessing a richer internal and emotional life. And yet everyone follows Superman as a natural leader, while Martian Manhunter is the creepy guy who always stands in the back of the group photo. Why?

In the comics, Martian Manhunter has his back-of-the-bus position simply because of seniority. Superman had been around for twenty years before Martian Manhunter showed up, and while MM might come in handy blowing out a forest fire or lifting up a bus, the Justice League in the ’60s couldn’t find much use for his talents. It took Bruce Timm and Co. to not only bring Martian Manhunter to life but to make him the most soulful, introspective and interesting member of the team.

The most obvious difference between Superman and Martian Manhunter, of course, is their looks. They’re both tall (MM is actually a good six inches taller than Supes) but Superman is white and handsome with a lantern jaw and a cleft chin, gimlet eyes, oodles of charisma and a charming spitcurl while Martian Manhunter is green, sepulchural, bald, sullen, beetle-browed and red-eyed.

But apart from the looks thing, why is it that Superman leads the Justice League around the world, punches robots, melts buildings and spaceships, destroys alien menaces and makes speeches to governmental bodies about the wise use of power, while MM can be found, every day, chained to a desk at the Watchtower, administering shift-changes and delegating task-work? Why does Martian Manhunter get no respect?

I think it has something to do with when their respective planets were destroyed. Superman was a baby when his father blasted him off of Krypton; he has no memory of it. All he knows is his his home planet was great and his parents loved him enough to give him a new lease on life, on a planet where he would be worshipped like a god. Martian Manhunter, on the other hand, was already married with a child when Mars was destroyed by an alien invasion. Superman has nothing but fond memories of his home, MM watched his wife and child murdered and his civilization destroyed before his eyes.

It’s broken him. He can’t just fly around smashing things because he’s seen too much flying around and smashing things in his life. It’s turned him into a scold and a gloomy gus. He’s always staring out windows and chastising the other members for being too quick with the violence. This sometimes makes him a wet blanket and a stick in the mud as he intones about the lessons he learned in seeing his home destroyed (in one issue of the comic, Flash, upon hearing the umpteenth iteration of MM’s origin story, finally sighs and says “Were all the Martians as whiny as you?”).

Then there’s the fire thing. The fire thing is lame. A shape-changing, building-lifting superhero should not be afraid of fire.

Maybe the fire thing has made MM gunshy. Maybe, despite his awesome powers, he’s happier in his administrative position, high above the Earth, unlikely to be caught in the clutches of a supervillain who might have, say, a book of matches and a pile of oily rags. MM stays in the Watchtower to avoid the embarrassment of a headline like “JUSTICE LEAGUE TRIUMPHS! Martian Manhunter felled by kid with Zippo.“

Then there’s the self-hate thing. MM failed his family, his civilization and his planet. In his mind he will never be free of his survivor guilt. Maybe that’s why he chooses to look like a tall, green creepy guy. I mean, keep in mind, the way we see MM is not how he sees himself. MM, in his “natural state,” looks like this:

That’s right — the creepy-green-guy look is how MM changes his appearance so as to look normal and not creep people out too much. He could look like Brad Pitt if he wanted to, but the MM look is what he chose. (In case he’s not creepy enough for you, keep in mind that the cape, trunks and pirate boots are all artificial; that is to say, MM is actually always naked. So when, say, Hawkgirl stands around the Watchtower with MM, she’s aware on some level that she’s standing next to, you know, a naked shape-changing Martian.)

But, point is, he has chosen to look the way he does. He has chosen to creep people out, to stay on the fringes of the group; his choice of look throws up a barrier to anyone who might get too close to him. Compare MM, moping around in his artificial creepy-guy state, with X-Men‘s Mystique, who prefers to strut around in her blue scaly state and only uses her shape-shifting powers to rob an armored car or bust a guy out of prison (there is the famous exchange between Nightcrawler and Mystique in X2: Nightcrawler asks “If you can change the way you look, why don’t you?” and Mystique sniffs “Because I shouldn’t have to.”) MM is not proud of the way he “naturally” looks, but at the same time he refuses to look “normal.” He shifts from “repulsive-looking” to “differently repulsive-looking.” It’s as though a Jew were to flee Poland and change his name from Greenberg to Lopez in order to sound “less Jewish.” That’s a level of self-disgust I’m not sure children should even be exposed to.

Then there’s the mind-reading thing, which, truth be told, is a burden to MM as much as it is an asset, and something he only uses when he really needs to. Otherwise, he is exposed to what everyone around him is really thinking, both about him and about the world. Martian Manhunter couldn’t live like Clark Kent, live a normal life with a job and friends and a love-interest. Because the natural, everyday masks that people wear don’t work for him. How could he be married if every time his wife kissed him good morning he could feel her resentment towards him or her subtle yearnings for the man next door? How could he go to work and carry on a job if he knew what petty, self-involved, disgusting thoughts were bubbling under the surface of the most mundane of everyday transactions?

Long Live the King

Today, January 8, is Elvis Presley’s birthday. He would have been 72.

When people learn I am an Elvis specialist, they often ask me, “Did Elvis Presley make any good movies?”

The answer, sadly, is no. Elvis Presley did not make any good movies.

There are, however, good Elvis Presley movies.

Elvis Presley made 31 feature films between 1957 and 1969 and, by any objective measure, they’re all terrible. Elvis movies, like James Bond movies, Star Trek movies, Bollywood musicals, Italian zombie movies and Japanese horror movies, cannot be enjoyed if compared to other “real” movies. They’re horrible. They’re beyond horrible. They’re stupid, boring and comically inept. You watch an Elvis movie and you can’t believe people went to see them, three times a year, for ten years. You watch an Elvis Presley movie and you can’t believe Elvis Presley was ever a star, much less the most important American artist of the twentieth century. You watch an Elvis movie and it seems unbelievable that Elvis was, when his film career began, the biggest star on the planet. You watch an Elvis movie and you have to remind yourself that these movies were made at the same time as Dr. Strangelove, West Side Story, Persona, Lawrence of Arabia, Jules et Jim, Bullitt, 2001: A Space Odyssey and Bonnie and Clyde, not to mention A Hard Day’s Night, Help! and Yellow Submarine. The biggest star on the planet couldn’t get a decent movie made around him to save his life. And as a result, he became no longer the biggest star on the planet.

There are a lot of reasons for this, which I can go into another time. Hint: they have to do with Col. Tom Parker being an evil, evil man.

For us Elvis fans, the movies’ flaws only make them more endearing. If you take them on their own terms, if you approach them with the same level of expectation you would have for, say, an episode of Here’s Lucy, they are perfectly engaging. As a chapter in Elvis’s career, they are an important step in his development as an artist — that is to say, they gave him twelve years of unbelievably crappy songs to sing so that he could “come back” in 1968.

THE WELL-INTENTIONED GENRE PIECES

Cineasts will say that King Creole, which co-stars Walter Matthau and is directed by Michael Curtiz, qualifies as a “good” Elvis Presley movie. But they are wrong. King Creole is a middling noir which, for some reason, stars Elvis Presley. Elvis tried to make a number of “real” movies, that is, movies that “just happened” to star Elvis Presley. These include Love Me Tender, a Civil War drama, Wild in the Country, a “juvenile delinquent” drama written by Barton Fink himself, Clifford Odets, and Flaming Star, a western drama, starring Elvis as a half-breed, directed by Don Siegel. It’s impossible to enjoy these movies as genre pieces because, well, because Elvis Presley is in them. He’s not believable as a cowhand, a half-breed or a down-on-his-luck kid. First, he’s not a very talented actor, second, he throws off charisma like a 1,000,000-watt lightbulb, blasting character, plot and every other actor offscreen (or into irrelevance). So you’ll have a couple of actors sitting around talking, pretending they’re in a “real movie,” and then ELVIS PRESLEY walks in and any sense of watching a “real movie” goes right out the window. It doesn’t get any better when he starts singing; there’s no reason why these movies would need to have singing in them at all (they were all developed as dramas — King Creole was originally about a boxer who gets into trouble with the mob [that is to say, it was originally a boxing movie]) –songs were shoehorned into existing scripts and it shows.

Of these four, King Creole has the best songs — that is, real Elvis Presley songs, not cringe-inducing novelty numbers (which sprout in abundance later, as we will see). The title song is a smash and the movie also includes “Hard Headed Woman, “Trouble” and “Crawfish.”

THE CREAM OF THE CROP

This is it. This is the best Hollywood could do. These three movies have it all. Elvis plays someone very much like himself, so there isn’t that awkward Elvis/reality schism. He sings, all-in-all, wonderful songs opposite real actors. He explodes off the screen. He is sexy, hot-headed, dynamic, graceful and bursting with energy. The direction and editing have zazz and pluck. In Viva Las Vegas, he even stars opposite a woman who can hold the screen with him. They are superlative entertainments and, more importantly, they are excellent showcases for Elvis’s talent. Viva Las Vegas also gets a gold star for being the one “Elvis Movie” that shows that the whole idea of an “Elvis Movie” can work as entertainment.

By “Elvis Movie” I’m speaking of a classically stupid, unbelievable, nonsensical concept that exists simply as an excuse for Elvis to sing, do something “exciting” (usually in front of obvious rear-screen projection) and kiss pretty girls. In the case of Viva, for instance, Elvis is a singing race-car driver who has to choose between wooing Ann-Margret and winning the big race. See? You wouldn’t go to see that movie. That’s a stupid idea for a movie. It is, in fact, a retarded idea for a movie. Imagine, if you will, George Clooney starring as a singing race-car driver who must choose between wooing Ann-Margret and winning the big race. You couldn’t get that movie made today. But it makes perfect sense as an Elvis Presley movie and is the model for the genre. The soundtrack also includes “You’re the Boss,” a number cut from the movie, that sounds astonishingly like Elvis singing on a Tom Waits record.

THE BIG-BUDGET ELVIS MOVIES

These movies are all professionally made, make no sense, are produced by Hal Wallis, made money and do what they’re supposed to do. I hate them. They are boring, pedestrian, and exist to make Elvis Presley “safe” for middle-class America.

There is a thing that happens in Elvis movies, where the composers can’t be bothered to come up with an original song so they re-purpose a copyright-free song and write new words to it. In Blue Hawaii it’s “Alouetta.” In another one it’s “Three Blind Mice.”

Girls! Girls! Girls! features “Song of the Shrimp,” where Elvis sings the tale of a shrimp who longs to climb aboard a shrimp boat to see the legendary land of Louisiana. All four of these movies include lullabies, and/or songs sung to mothers.

MY PERSONAL FAVORITES

You always love your retarded children more than the others. Producers other than Hal Wallis discovered that you could make more money with a cheap Elvis movie than you could with an expensive Elvis movie. And this accounts for the bulk of the Elvis filmography, what I like to think of as the “real” Elvis movies. They have the texture of Formica, the depth of cellophane and the complexity of a gallon of buttermilk. They don’t feel like movies at all, they feel like episodic television. This week on Elvis, Elvis is caught behind the Iron Curtain and must match wits with batty spies in order to get to his big singing gig! They are uniformly genial, sporadically charming and cinematically dead on arrival.

In each one Elvis plays a singing racecar-driver/speedboat-driver/cliff-diver/helicopter-pilot/boxer/hillbilly who has to win the race or win the big fight or solve the mystery. In Tickle Me he has to hunt for buried treasure in an abandoned western town which may or may not be haunted. Four decades of Scooby-Doo adventures have robbed this movie of much of its surprise.

Novelty songs abound, and I pretty much adore every song from every one of these movies. Girl Happy has the best of them, a charming number called “Fort Lauderdale Chamber of Commerce.” (yes, you read that right.) Paradise Hawaiian Style features “A Dog’s Life,” which is sung to, who else, a helicopter full of dogs, and also “Queenie Wahini’s Papaya.” Fun in Aculpulco has “No Room to Rhumba in a Sportscar.” Tickle Me, the cheapest of the movies, actually benefits from not having any “new” songs for Elvis to sing. Instead, he gets to sing some actual blues numbers from his post-army years, and one is actually reminded for a moment that he is one of the most significant American talents of all time.

It Happened at the World’s Fair includes a cameo by the young Kurt Russell, who plays a snot-nosed brat who kicks Elvis in the shin. It also contains the only intentionally funny joke in the Elvis filmography: Elvis walks down a street by himself, flips through his “little black book,” looking up a girl who lives nearby. He finds her name and recites “Mary. Hmm. 36-24 — pause — Maple Street.” He then cocks his eyebrows and moves on.

Clambake holds a special place in my heart. It represents what may possibly be the nadir of Elvis’s personal life. He had put on thirty pounds or so, was taking spiritual advice from his barber, and had cracked his head open on a sink the night before shooting began during one of his adventures in pharmacology. As a result, his hair is combed into permanent, shellacked bangs and the belted leisure suits he wears make him look like Ubu Roi. It also features the worst song, bar none, of his career, a “High Hopes” knockoff called “Confidence,” which he sings to a playground full of kids. Now, keep in mind that, ten years earlier, Elvis Presley was enraging parents, scandalizing censors and making teenage girls go weak in the knees. Now he’s singing to children about building confidence. It’s an obscenity. I love it.

THE ALSO RANS

What does it say about a movie when it just isn’t quite as good as a low-budget Elvis movie? And yet, these movies, for whatever reason, don’t make the cut. Easy Come, Easy Go, in spite of being a Hal Wallis production, is a stupefying atrocity, where Elvis, no kidding, plays a singing scuba diver who must battle evil hippies in order to find sunken treasure. Live a Little, Love a Little is a Mad Ave comedy that co-stars Rudy Vallee and features a “psychedelic” number, “Edge of Reality,” where Elvis sings to a man in a Great Dane costume. Frankie and Johnny is a period piece which should, theoretically, give Elvis a chance to explore the roots of his music, but which does not.

MUST TO AVOID

Harum Scarum isn’t just a bad Elvis movie, it’s one of the worst movies ever made by anyone. Agonizingly boring, impossible to sit through, full of crappy songs, cheap sets, bored actors, nonexistent editing and uninspired writing and direction. Stay Away, Joe, in addition to having perhaps the worst title of any Elvis movie (they might as well have called it Stay Away, Audience), features Elvis, I could not invent this, singing a song to an impotent bull.

THE LATE EXPERIMENTS

Late in his film career, Elvis abruptly stopped making “Elvis Movies” and returned to trying to make “real” movies. Charro! is a Clint Eastwood western without songs, The Trouble With Girls is a bizarre, unwieldly, Altmanesque portrait of life on the Chatauqua circuit circa 1929, and Change of Habit is an urban “problem drama” with Elvis starring as a ghetto doctor who falls in love with a nun. The nun (Mary Tyler Moore) must choose between Jesus and Elvis.

They all suck, although Change of Habit does hold the viewer in a certain stateof ghastly fascination.

Empire Burlesque

Two men’s lives collide with destiny. One holds a flashlight, the other a knife. One walks away, the other toward. Both are lit from behind. What do they want?

Warning: Spoilers abound.

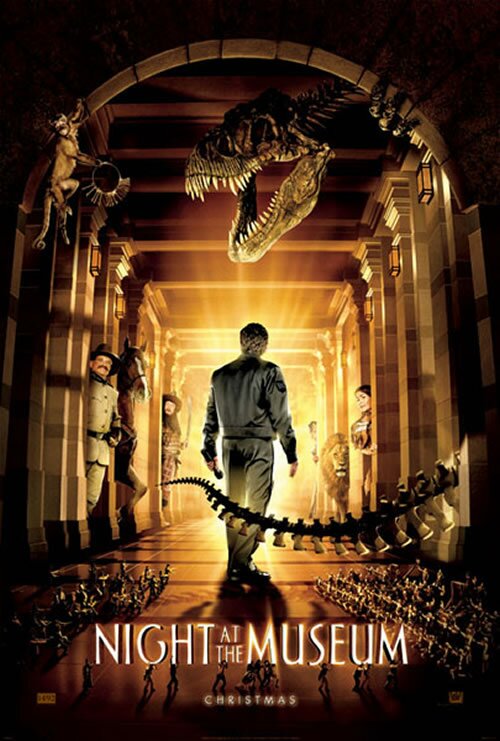

I saw two movies over the holidays that, on the surface, don’t seem to have that much to do with one another (apart from the similarities in the poster design). One is a genial special-effects comedy, the other is a dark historical adventure.

Their hidden link is that they are both about the follies of empire. This may not have occurred to me if I hadn’t seen Night at the Museum twice in one 24-hour period, at the behest of my five-year-old son.

The setup, for the unaware, is: Ben Stiller gets a job as a night-watchman at New York’s Museum of Natural History. At night, we learn, the exhibits come to life, and hilarity ensues.

The first time watching this movie I kept wondering why the filmmakers had included a whole bunch of stuff that is not found at the Museum of Natural History, like an Egyptian mummy and an Eastern Island head and a mannikin of Sacajawea. I figured they couldn’t think of enough comedy bits for the T-Rex skeleton and the monkey to do, so they gave Ben some humans to interact with. But watching the movie a second time revealed its light-hearted but still subversive message. And, as always, my analysis begins with the question “What does the protagonist want?”

Ben believes in the Horatio Alger myth. He wants to build a business empire based on what we screenwriters like to call a “harebrained scheme.” But his dream has not panned out and for now his make-do goal is to “get a job.” He’s at a loose end and is looking for a focus for his life. He is, essentially, a child-man standing at the threshold of adulthood, wondering how he’s supposed to behave, because the American dream of getting to live however you want isn’t working out for him.

He gets the job guarding the museum. The prospect of this is a little unnerving for him, becoming the caretaker of a thousand dead harebrained schemes. Personages no less than Dick Van Dyke, Mickey Rooney and Bill Cobbs (the Magical Negro from The Hudsucker Proxy) play the outgoing guards, who appear to be losing their minds. There’s some comedy with the T-Rex skeleton and the monkey, but then Ben must deal with what at first appears to be a random selection of historical persons: some cowboys, some Roman soldiers, Attila the Hun, Teddy Roosevelt, some Neanderthals, etc. They run rampant over Ben and the museum and he is quickly overwhelmed. The succeeding two acts of the movie concern Ben’s efforts to control these various uncontrollable exhibits and bring them to heel. On the way he finds confidence and shows his estranged son how to be a man.

The second time around I started to keep track of exactly who Ben deals with. Because it’s not just “some cowboys,” it’s the men who constructed the railroad to the west, and their “Railroad West” diorama is next door to the “Ancient Rome” diorama and across the hall from the “Ancient Mayan” diorama (the Mayans are too savage for Ben and must be shut up behind glass at night — I wonder if the jab at Apocalypto is intentional or accidental). So here are three empires represented, Mayan, Roman and American. Two of them failed, as all empires eventually do, and one is in the process of failing right now. And then the rest of the characters fall into place — Attila the Hun, Teddy Roosevelt, Sacajawea, the Egyptian mummy, the Civil War soldiers, even the dinosaurs, all representative of empires now consigned to the dustbin of history. Ben follows a bronze statue around through the movie, trying to remember his name — is it Galileo? Cortez? No, it turns out to be Christopher Columbus (whose namesake also happens to be one of the producers of the movie). Vikings and Chinese terra-cotta soldiers flit through the background of scenes and the Easter Island head provides a solemn centerpiece, a reminder of just how quickly a civilization can fall apart.

The theme of Night is perhaps not empire itself but the theft and plunder that goes along with it. The adventure begins with the Tyrannosaur, the largest predator to ever live on land, and moves on to the living diorama figures, who must be among the tiniest. Ben is in danger of losing his son to his ex-wife’s bond-trader husband, who must be counted as a modern-day financial predator, another imperialist constructing what he assumes will be another 1000-year empire. To drive the point home, the outgoing guards, in Act III, we learn, are not going to leave the museum without looting it first, and Ben convinces the different warring factions in his imperialist hodgepodge to set aside their differences in order to stop the plunder of their own resources. Ben learns to give up his own dreams of entrepreneurial empire, the warring museum exhibits abandon their imperial urges, peace reigns at the museum and it’s a wild disco party every night. And that, the movie seems to be saying, is what it means to be a man.

Apocalypto is much more straightforward in its analysis of fallen empires. What’s surprising about it is how Mel Gibson seems to be saying that empires fall for one reason and one reason only — religious fundamentalism. The protagonist is a simple tribesguy of a peaceful bunch of jungle people, who gets rounded up by a band of hunters whose job seems to be supplying the local temple with fresh human sacrifices. The priests atop the temple are portrayed as cynical, manipulative snake-oil peddlers who don’t believe a syllable of the dogma they preach to the masses. Our guy escapes becoming a sacrifice and makes it back to his village, only to arrive on the very day the Spanish show up, with their bright red crosses on the sails of their boats and Bible-carrying priests leading the rowboats up to the beach. If our protagonist could conceive of a frying pan, he would no doubt exclaim that he was now out of it and into the fire.

I read an interview that complains thatGibson is trying to tell us that the Spanish came to Mexico to “save” the Mayans from their savage, godless ways. I disagree; regardless of what Gibson’s religious views are, the Spanish in the movie are not portrayed as saviors, they are portrayed as extremely weird strangers who are to be avoided at all costs. The protagonist’s wife, looking down at the boats unloading on the shore, says something like “Who are those people? What do they want?” to which the protagonist says something like “I don’t know who they are, but our best bet is to get the hell away from them, head back into the jungle, find a way to start over.” Which is where the movie leaves us.

That interview, and others, criticize Apocalypto severely for its view of Mayan culture. Some of their criticisms seem overly sensitive to me, others seem to miss the point entirely. The claim that the movie presents Mayans as savages seems wrong; if anything it presents them as sophisticated to the point of decadence; still not a positive portrayal, but the point of the “city” sequence of the movie is that we’re seeing the bustling metropolis from the point-of-view of a prisoner being brought to a temple to be sacrificed. The whole thing goes past as it should, as a bewildering blur of sensations, not as a sober, even-handed analysis of a culture. Other critics say that the Mayans were master mathemeticians and astronomers, and therefore could not possibly have been swayed by superstition or religious hocus-pocus. Well, guess what? Americans in 2007 are master mathemeticians and astronomers, too, and we get suckered by superstition and religious hocus-pocus on a daily basis.

Apocalypto, as far as I can tell, gets the same things wrong about Mayan culture as Spartacus gets wrong about Roman culture, namely, compressing centuries of history and thousands of miles of empire into a single narrative. This is regrettable but utterly in keeping with Hollywood tradition. Hollywood routinely fictionalizes and compresses historical events even within the living record, from Dances With Wolves to The Untouchables to The Deer Hunter. I predict that, within the lifetime of the younger readers of this blog (say,

), there will be a serious historical drama about America that will show Abraham Lincoln teaming up with George Washington to save Sacco and Vanzetti.

(Those who stay for the credits of Night at the Museum get treated to the spellbinding sight of Dick Van Dyke and Mickey Rooney dancing again. Van Dyke does not get a chimney broom, but is granted a mop.)