Empire Burlesque

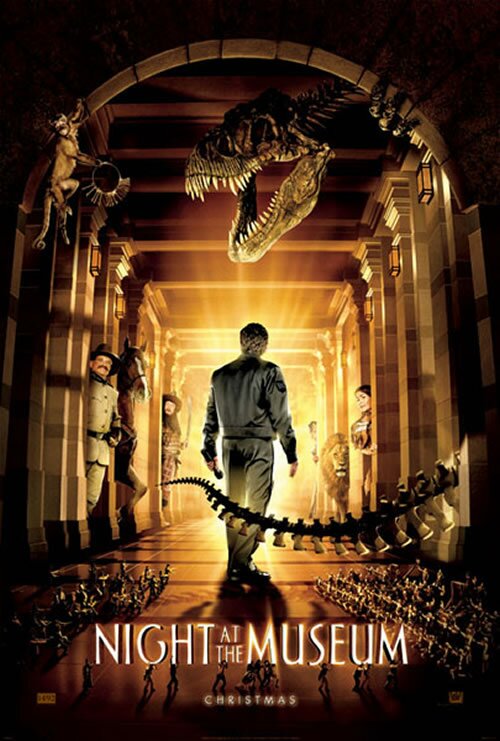

Two men’s lives collide with destiny. One holds a flashlight, the other a knife. One walks away, the other toward. Both are lit from behind. What do they want?

Warning: Spoilers abound.

I saw two movies over the holidays that, on the surface, don’t seem to have that much to do with one another (apart from the similarities in the poster design). One is a genial special-effects comedy, the other is a dark historical adventure.

Their hidden link is that they are both about the follies of empire. This may not have occurred to me if I hadn’t seen Night at the Museum twice in one 24-hour period, at the behest of my five-year-old son.

The setup, for the unaware, is: Ben Stiller gets a job as a night-watchman at New York’s Museum of Natural History. At night, we learn, the exhibits come to life, and hilarity ensues.

The first time watching this movie I kept wondering why the filmmakers had included a whole bunch of stuff that is not found at the Museum of Natural History, like an Egyptian mummy and an Eastern Island head and a mannikin of Sacajawea. I figured they couldn’t think of enough comedy bits for the T-Rex skeleton and the monkey to do, so they gave Ben some humans to interact with. But watching the movie a second time revealed its light-hearted but still subversive message. And, as always, my analysis begins with the question “What does the protagonist want?”

Ben believes in the Horatio Alger myth. He wants to build a business empire based on what we screenwriters like to call a “harebrained scheme.” But his dream has not panned out and for now his make-do goal is to “get a job.” He’s at a loose end and is looking for a focus for his life. He is, essentially, a child-man standing at the threshold of adulthood, wondering how he’s supposed to behave, because the American dream of getting to live however you want isn’t working out for him.

He gets the job guarding the museum. The prospect of this is a little unnerving for him, becoming the caretaker of a thousand dead harebrained schemes. Personages no less than Dick Van Dyke, Mickey Rooney and Bill Cobbs (the Magical Negro from The Hudsucker Proxy) play the outgoing guards, who appear to be losing their minds. There’s some comedy with the T-Rex skeleton and the monkey, but then Ben must deal with what at first appears to be a random selection of historical persons: some cowboys, some Roman soldiers, Attila the Hun, Teddy Roosevelt, some Neanderthals, etc. They run rampant over Ben and the museum and he is quickly overwhelmed. The succeeding two acts of the movie concern Ben’s efforts to control these various uncontrollable exhibits and bring them to heel. On the way he finds confidence and shows his estranged son how to be a man.

The second time around I started to keep track of exactly who Ben deals with. Because it’s not just “some cowboys,” it’s the men who constructed the railroad to the west, and their “Railroad West” diorama is next door to the “Ancient Rome” diorama and across the hall from the “Ancient Mayan” diorama (the Mayans are too savage for Ben and must be shut up behind glass at night — I wonder if the jab at Apocalypto is intentional or accidental). So here are three empires represented, Mayan, Roman and American. Two of them failed, as all empires eventually do, and one is in the process of failing right now. And then the rest of the characters fall into place — Attila the Hun, Teddy Roosevelt, Sacajawea, the Egyptian mummy, the Civil War soldiers, even the dinosaurs, all representative of empires now consigned to the dustbin of history. Ben follows a bronze statue around through the movie, trying to remember his name — is it Galileo? Cortez? No, it turns out to be Christopher Columbus (whose namesake also happens to be one of the producers of the movie). Vikings and Chinese terra-cotta soldiers flit through the background of scenes and the Easter Island head provides a solemn centerpiece, a reminder of just how quickly a civilization can fall apart.

The theme of Night is perhaps not empire itself but the theft and plunder that goes along with it. The adventure begins with the Tyrannosaur, the largest predator to ever live on land, and moves on to the living diorama figures, who must be among the tiniest. Ben is in danger of losing his son to his ex-wife’s bond-trader husband, who must be counted as a modern-day financial predator, another imperialist constructing what he assumes will be another 1000-year empire. To drive the point home, the outgoing guards, in Act III, we learn, are not going to leave the museum without looting it first, and Ben convinces the different warring factions in his imperialist hodgepodge to set aside their differences in order to stop the plunder of their own resources. Ben learns to give up his own dreams of entrepreneurial empire, the warring museum exhibits abandon their imperial urges, peace reigns at the museum and it’s a wild disco party every night. And that, the movie seems to be saying, is what it means to be a man.

Apocalypto is much more straightforward in its analysis of fallen empires. What’s surprising about it is how Mel Gibson seems to be saying that empires fall for one reason and one reason only — religious fundamentalism. The protagonist is a simple tribesguy of a peaceful bunch of jungle people, who gets rounded up by a band of hunters whose job seems to be supplying the local temple with fresh human sacrifices. The priests atop the temple are portrayed as cynical, manipulative snake-oil peddlers who don’t believe a syllable of the dogma they preach to the masses. Our guy escapes becoming a sacrifice and makes it back to his village, only to arrive on the very day the Spanish show up, with their bright red crosses on the sails of their boats and Bible-carrying priests leading the rowboats up to the beach. If our protagonist could conceive of a frying pan, he would no doubt exclaim that he was now out of it and into the fire.

I read an interview that complains thatGibson is trying to tell us that the Spanish came to Mexico to “save” the Mayans from their savage, godless ways. I disagree; regardless of what Gibson’s religious views are, the Spanish in the movie are not portrayed as saviors, they are portrayed as extremely weird strangers who are to be avoided at all costs. The protagonist’s wife, looking down at the boats unloading on the shore, says something like “Who are those people? What do they want?” to which the protagonist says something like “I don’t know who they are, but our best bet is to get the hell away from them, head back into the jungle, find a way to start over.” Which is where the movie leaves us.

That interview, and others, criticize Apocalypto severely for its view of Mayan culture. Some of their criticisms seem overly sensitive to me, others seem to miss the point entirely. The claim that the movie presents Mayans as savages seems wrong; if anything it presents them as sophisticated to the point of decadence; still not a positive portrayal, but the point of the “city” sequence of the movie is that we’re seeing the bustling metropolis from the point-of-view of a prisoner being brought to a temple to be sacrificed. The whole thing goes past as it should, as a bewildering blur of sensations, not as a sober, even-handed analysis of a culture. Other critics say that the Mayans were master mathemeticians and astronomers, and therefore could not possibly have been swayed by superstition or religious hocus-pocus. Well, guess what? Americans in 2007 are master mathemeticians and astronomers, too, and we get suckered by superstition and religious hocus-pocus on a daily basis.

Apocalypto, as far as I can tell, gets the same things wrong about Mayan culture as Spartacus gets wrong about Roman culture, namely, compressing centuries of history and thousands of miles of empire into a single narrative. This is regrettable but utterly in keeping with Hollywood tradition. Hollywood routinely fictionalizes and compresses historical events even within the living record, from Dances With Wolves to The Untouchables to The Deer Hunter. I predict that, within the lifetime of the younger readers of this blog (say,

), there will be a serious historical drama about America that will show Abraham Lincoln teaming up with George Washington to save Sacco and Vanzetti.

(Those who stay for the credits of Night at the Museum get treated to the spellbinding sight of Dick Van Dyke and Mickey Rooney dancing again. Van Dyke does not get a chimney broom, but is granted a mop.)

Excellent stuff

Todd – your entries continue to be insightful, entertaining and really well written. Someone should give you a newspaper column!

Pssst. Astronomers, not astrologists.

Ah. Good point.

What kind of character in a museum wouldn’t be a “representative of empires now consigned to the dustbin of history”? Or are you saying that’s why they chose the museum setting?

At New York’s American Museum of Natural History, where the movie is specifically set, the emphasis is on the evolution of animal life, not world history. They are very strict about this, which is why it’s sometimes hard to figure out where the animals are you want to see, because the museum is laid out in evolutionary order, not order of coolness.

There are some dioramas of Indian and Eskimo life, and some displays of cultural artifacts, such as the Native American boat they have in their south lobby, but there are no wax figures of Lewis and Clark, Attila the Hun or African tribesmen. There is, in fact, no wax figure of Teddy Roosevelt on a horse, even though he founded the museum and there is a copper sculpture of him on a horse (posed with two Indian guides, also featured in the movie) on the steps outside. There is no Easter Island head, no room full of dioramas of dead empires, no dummies in Civil War costumes. New York’s famous Egyptian artifacts are across town at, of all places, the Metropolitan Museum of Art (as well as the Brooklyn Museum, which does also include a broad swath of world cultural history as well). There are wax figures of Neanderthals, as befitting a natural history museum, but there is no bronze statue of Christopher Columbus in the lobby, no terra-cotta warriors from long-gone Chinese dynasties.

The picture book the movie is based on is also set at AMNH, but only concerns the guard’s attempts to deal with the teeming animal life in the museum. The larger animals must be taken for walks, there are huge deliveries of food every night, etc. The book makes no references to any historical personages at all; these were clearly additions the filmmakers made for a specific purpose.

I understand all that. But your point seemed to be that, when choosing things to add that aren’t in the actual museum, they chose (either consciously or subconsciously) particular human characters that represent fallen empires. My question is, what human characters could they have chosen (to appear in a museum) that don’t represent fallen empires?

From American history, they could have chosen anonymous settlers and Native Americans instead of the builders of the western railroad and Sacajewea with Lewis and Clark (who are presented as the archetypal Stupid White Men, in opposition to Sacajewea’s pure, questing soul). They could have put in dioramas of a Roman marketplace instead of an army of centurions bent on conquest. They could have chosen any number of anonymous persons and artifacts celebrating or illuminating a culture instead of critiquing its imperialist tendencies (come to think of it, I wonder how Napoleon escaped their notice). They could have put in Annie Oakley or Vincent Van Gogh or Martin Luther King or Mohandes Gandhi. They could have put some females in any of their dioramas, which are plentiful in the dioramas at AMNH but which are totally absent in Night at the Museum.

The imperialism theme is made explicit about halfway through the movie, where they show the railroad workers trying to blow a hole through the wall of their diorama in order to finish the railroad, while the Romans next door use a battering ram to try to break down the same wall. The railroad workers (in the person of Owen Wilson) don’t know why they have to finish the railroad, they only know that they are there to illustrate the concept of “manifest destiny.” Meanwhile, the Romans (in the person of Steve Coogan) crow that they must “expand or die.” When asked why these expanding empires must be in conflict with each other when the museum is so large, they can only offer that they are guys, and must therefore seek conflict with each other. “That’s what guys do,” offers Wilson, a little sheepish at having his motivations analyzed.

I just finished compiling my personal list of the best films of 2006. Suffice to say, these two weren’t even on my list of films to see in the first place.

In the case of Night at the Museum, it was because the commercials were hammered home enough while I was watching The Daily Show and The Colbert Report that I couldn’t help but get sick of them, and in the case of Apocalyptico, it was because I’m sick of Gibson, period. It’s the same reason why I can’t see myself watching a Tom Cruise movie for the foreseeable future.

P.S. – Those posters are taking an incredibly long time to load for me. I know I’m on dial-up here, but damn. I’ve been composing my comment for five minutes and my browser hasn’t even finished loading the first one yet.

I probably would not have seen Night at the Museum if AMNH were not my son’s favorite place on Earth, let alone see it twice in 24 hours (let alone sit in the front row both times, but that’s another story). Once there, however, I found the movie more interesting and layered than the advertisements make it look.

Concerning Mel Gibson, I’m not quite sure where the hatred toward him comes from. Lots of people say stupid things they may or may not believe when they’re drunk. Elvis Costello did back in the day, but no one seems to hold it against him any more. Spike Lee has said equally hateful things when cold sober, but I’ll still go see his movies. If Mel Gibson forms an organization dedicated to persecuting Jews, that’s one thing; if he makes an idiotic remark while drunk, that’s another. If David Mamet can forgive Mel Gibson, I suppose I can too.

As for Tom Cruise, I don’t follow the gossip tabloids so I am still largely in the dark about whatever his insane public behavior is supposed to be. He’s one of the most talented and significant movie stars of our time and I see no reason to avoid his movies on moral grounds. As for his religious beliefs, Scientology seems to me to be no more nonsensical, predatory, cynical or sinister than any other major western religion.

I don’t know what to say about the posters loading, they’re the smallest files I could find on line. Perhaps your server has a cold.

My problem is not that I hate them, but rather that I’m burned out on them from hearing about them so much. And it’s not like I follow the tabloids, either, it’s just been impossible to avoid hearing about Gibson’s drunken ramblings and Cruise’s personal vendetta against psychiatry and so forth. Maybe in a couple years I’ll have enough distance to be able to see their films simply as films (like it was several years before I could watch Woody Allen’s Husbands and Wives), but right now their media personas are overshadowing their talents.

Yeah, I felt the same way about Leonardo DiCaprio for a while. I was the only girl in high school that didn’t find him dreamy and I didn’t see Titanic until it was on cable. I mean, his face was on every magazine and billboard and TV show and every where you turn people are talking about him….it just made him so unappealing to me.

Then I saw Gangs of New York and loved it. The Leo hype melted away. *shrugs* Scorsese can just work miracles, I guess. 😉

Well, Husbands and Wives is an astonishing movie no matter who made it.

Indeed, but was anybody truly about to see that in 1992? From what I could see, everybody — critics and moviegoers alike — was far too wrapped up in finding clues to the dissolution of Woody & Mia’s relationship — and reading far too much into the Woody & Juliette Lewis subplot.

i guffawed at the;

“there will be a serious historical drama about America that will show Abraham Lincoln teaming up with George Washington to save Sacco and Vanzetti.”