X-Men: First Class part 11

The most striking, most unusual feature of the screeplay for X-Men: First Class is that it does not have a traditional end-of-second-act low point. In the typical superhero narrative, the story is: villain appears, superhero fights, villain triumphs, superhero comes back from defeat. That doesn’t happen here, because First Class, lest we forget, is a romance. The romantic comedy goes: boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl back, but a straight romance doesn’t need a happy ending, and in fact can have a tragic ending, as in Romeo and Juliet or The Fly. In the romantic tragedy, the two leads want to be together but cannot — the forces arrayed against their union are too great. The forces arrayed against Erik and Xavier are all internal, and deal with their past and upbringing, irreconcilable questions of identity and personality. Erik cannot wake up in the morning and no longer be a persecuted Jew, and Xavier, for all his psychic power, cannot imagine life in Erik’s shoes, because he’s always had everything he needs. If they could change, if they could reconcile their differences (that’s why the movie spent the first act underlining those differences), they could stay together and save the world, but the narrative drives them irrevocably toward breakup and tragedy.

So what is the structure of First Class? I would say it’s: Act I, Erik and Xavier head on a path toward each other with Shaw as their common enemy, culminating in their meeting; Act II, Erik and Xavier pursue Shaw together and fall in love through the action of doing so, culminating in the raid on the Russian general’s house; Act III, a retreat to more internal matters as Xavier attempts to temper Erik’s anger with love while he trains his recruits; and Act IV, where Erik’s and Xavier’s relationship is put to the test: can they work together, save the world and be happy, or will the polar opposites of their pasts hinder their efforts and tear them apart, simultaneously bringing the end of the world? (“The end of the world” is an overused trope in superhero narratives — hell, a lot of narratives — but when it’s tied to a love story it become elevated; a romantic breakup often does feel like the end of the world, First Class merely literalizes it.)

So, as we move into Act IV, our team, our shaky team of ill-fitting misfits, whose agendas are disparate and whose various romantic entanglements are unsettled, “suit up,” put on their uniforms, their uniforms that declare their Otherness (the last thing Erik, a Holocaust-era Jew, could possibly want to do at this point), and head into battle. Hank has provided them with an airplane, a Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird to be precise, a plane that wouldn’t fly for another two years but hey, we expect Hank to have access to toys ahead of time. Hank has also, to his chagrin, turned into Beast. Mystique, for her part, likes the new Hank — what woman would prefer a shy, awkward geek to a brainy beast?

In the waters outside Cuba, Russian and US ships head toward one another at the “embargo line.” Neither the Russian or American commanders want conflict, which is, truth be told, the position of any soldier. Soldiers are always sent into battle to kill each other over things decided upon by politicians in dark rooms thousands of miles away, and the tension of the standoff scenes of First Class, like the rest of the narrative, view the soldiers discomfort through the lens of fantasy: it’s one thing to dread combat because some soft-bottomed politician wants it, it’s something else to dread it because a deranged mutant no one has even seen wants it. Shaw’s mutation, don’t forget, is “absorption of power,” it’s central to his personality that he should gravitate to a situation where he cannot lose: even a nuclear blast would only serve to strengthen him.

The Russian ship carrying the bombs to Cuba has been taken over by Azazel, who ignores orders from the Soviet HQ (someone high-level has come to his senses) to return to port. Xavier, taking matters into his own hands (or head, anyway) hijacks a Russian officer and has him fire upon his own ship, destroying the nukes. Good going, Xavier! You just turned that Russian officer into a war criminal and a traitor!

This, alas, is where history and First Class diverge. There was no mysterious blowing-up of any Soviet cargo ship, there was no battle at all (not that day, anyway, and I should know — it was my first birthday!), and the remainder of the narrative moves forward on a fantastical action-adventure template.

Shaw, his party spoiled, moves to his “back-up plan,” which involves soaking up energy from his nuclear reactor. In this way he communes with the god of the age, the mysterious atom that held such sway over the world in those dark days; a nuclear reactor is like his Ark of the Covenant. (Like a lot of back-up plans, this one isn’t very good: Shaw never gets around to explaining what he’s going to do with his nuclear-powered body once he gets it.) Xavier, acting as a kind of wireless relay, sends Banshee to find Shaw’s submarine and cheers Erik on to lift it out of the water. “Remember, the point between rage and serenity” is the thought he places in Erik’s mind, ever the bossypants, as he struggles to control Erik in the only way he can. “Lift that sub,” he’s saying, “but do it my way.” Erik, for his part, is willing to surrender to Xavier’s control, and we can see in his face the conflict of emotions. He does love Xavier, he loves his power and his ability to control, but his identity, his pride, won’t let him surrender.

As Erik raises the submarine out of the water, Riptide counters with a tornado, Erik drops the submarine on a beach, the X-jet crashes. Miraculously, everyone, even normal-human-being Moira, is perfectly okay. (How Shaw managed to keep a grip on his nuclear reactor as his submarine flew, crashed, broke apart and rolled over is not explained.)

Various folks fight: Beast and Azazel, Havok and Angel, Banshee and Angel, Erik and Riptide, Mystique and Beast and Azazel, so forth. Events move too quickly for the viewer to ask the typical X-Men narrative question, the one that begins “Why don’t they just…?” Xavier does what he can with mind control, although he can apparently only concentrate on one mind at a time, in this case Erik’s, as he guides him toward Shaw. That is, he guides Erik towards his goal of revenge, knowing that it is bad for Erik’s soul, and not realizing the extent to which it will ruin their love.

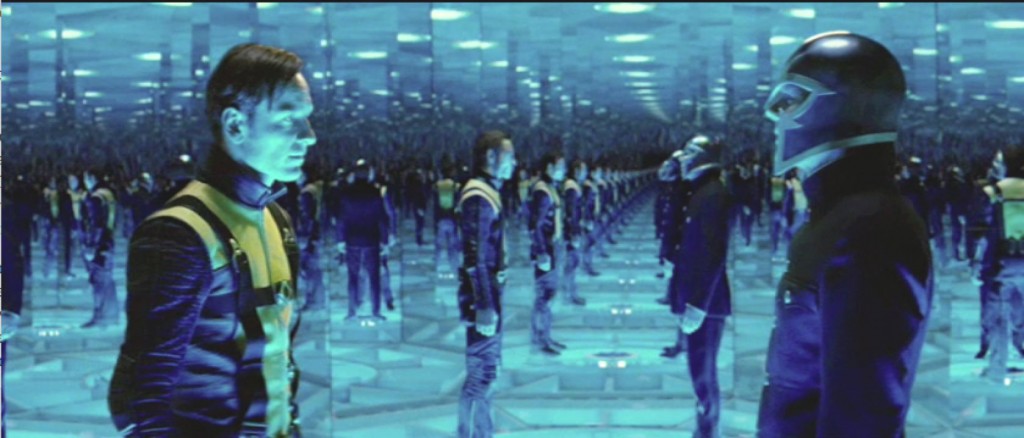

Erik finds Shaw in a literal hall of mirrors at the heart of the submarine, and learns that Shaw cannot be beaten with physical force. Shaw, the silver-tongued devil, tries to tempt Erik to the dark side (maybe that’s why the helmet, to look more like Darth Vader). He apologizes for “everything that happened in the camps,” something that his historical counterpart, Eichmann, could not bring himself to do, then explains that it was all for his own good, exactly like an abusive father. Shaw is, really, Erik’s abusive father, and everyone knows how the Abusive Father narrative ends: the son destroys him but inherits his poison. He removes Shaw’s anti-mind-control helmet and puts it on himself, his decisive moment: he loves Xavier, but he will not be controlled, by anyone. Xavier’s and Erik’s breakup, like their meeting and their consummation, are handled through an intermediary — Xavier must watch, through Shaw’s eyes, as Erik betrays everything Xavier has wanted for him. Erik has remembered, he’s had the perfect weapon to kill Shaw all along: that coin that Shaw gave him in payment for his mother’s death. Erik still has the coin, and is now ready to pay it back, and he sends it through the head of the immobilized Shaw. The great irony is that he needs Xavier’s cooperation to pull off this stunt, it’s the only way he could do it. And so Xavier must watch helpless as Erik not only murders Shaw but any chance of happiness with Xavier. He, in fact, makes Xavier an unwilling accomplice to his murder, his revenge, forces him to become the thing he said he would never be, the thing he has always blithely assumed he’d never have to be: an ambassador for vengeance. Xavier, in this moment, is also helpless: he can’t release Shaw from his mental grip, that would allow Shaw to kill Erik, the man he loves. His agony in the moment Erik’s chilling revenge is palpable: he’s not only seeing Erik turn evil, he’s experiencing Shaw’s death — in slow motion.

Back in Washington, Stryker (remember him?), the Cuban Missile Crisis over, suggests destroying the island where all the mutants have congregated, exactly as Erik has feared the Establishment would. (Stryker’s panic over the possible Mutant Takeover was sparked, the viewer will recall, by Mystique’s impersonation of him.) McCone, bless his heart, disagrees with Stryker, but only because there’s a human — Moira, his ex-typing-pool agent — on the island with them. How Stryker has gotten to the point where he can overrule the Director is not explained, but Stryker’s own arc, from underling to combatant to loose cannon, has been brief but well-defined.

Erik has seen all this coming, of course — he’s seen the demonization of the Other first hand. (He emerges from Shaw’s submarine with Shaw in a crucified pose — an odd choice, making Shaw Christ and Erik a vengeful Jew.) He’s completed his transition from victim to leader, from Erik to Magneto. (And, judging from his accent, from English to Irish, but that’s another matter. On second thought, the shift in Michael Fassbender’s accent may be intentional, from oppressor to oppressed, to better gain followers.) The element that had always threatened Erik’s relationship with Xavier, the suspicion and hatred of the Other, Xavier learns, is real and present, as the humans aim their guns for the island. The soldiers who, just minutes earlier, quaked at the thought of an international conflict, now happily fire on a tiny island with a handful of freakish civilians on it. The look on Moira’s face as she realizes her doom is priceless. Here she is, a high-ranking member of the Establishment, now slated to become collateral damage at the moment of her saving of the world. (On the other hand, as a young woman within that Establishment, she still counts as Other.)

Erik, of course, has the power to stop the incoming missiles, and has the power to dismantle them as well, to make them harmless. Xavier, at this moment, makes a terrible critical error — he defends the soldiers on the ships as innocent men only following orders — the Eichmann defense. Erik’s response, “Never again,” of course, is the motto of the western conscience (and, as Marie Brennan brings up in the comments, it is the slogan of the Jewish Defense League — a quite daring move, to equate Erik’s arc to that of European Jews from Auschwitz to Israel), but Erik here appropriates that sentiment to his own twisted purposes. He sends the missiles back to their ships as the ship’s captains suddenly turn noble again, realizing they’re about to die at the hands of a vengeful Other. Xavier, his mind-control tricks useless now, tries to distract Erik by tackling him. When that fails, Moira tries to shoot him. She fails, and Erik deflects one of her bullets into Xavier’s back. Crippling his friend is enough to distract him and the missiles crash safely into the waves.

Erik, pressing his advantage over the crippled Xavier, tries one last time to bring his friend to his side, but Xavier, even in his physical agony, cannot see Erik’s point of view. His goodness, his optimism, born of comfort and security, is too ingrained in him. Holding Xavier, Erik looks like he wants to kiss him, and I’m reminded that the helmet, that barrier, is Erik’s last defense against intimacy, like a chastity belt he wears on his head, to keep himself, his vengeance, his identity, pure. He loves Xavier but he cannot trust him, as well he should not, we’ve seen Xavier use plenty of people’s minds against them to think that he wouldn’t do it to anyone if it suited his purposes — out of goodness, of course, but that is always the way of the powerful liberal, always manipulating people’s minds for their own good.

Mystique joins Erik, as do Shaw’s men, but not before Mystique breaks up with Beast in her own way, reminding him to be “mutant and proud,” sowing the seeds of doubt in his mind. The others, Xavier’s recruits, go to his side, the good acolytes, the “kids from the bad side of the tracks” that have joined Xavier’s Boys’ Town.

Xavier ends where he began, at his home in Westchester, the carefree rogue now housebound forever, pushed in a wheelchair by a woman he once tried to seduce. Moira insists that she will never, ever tell the government where Xavier lives, as though a huge estate in upstate New York, where Xavier has lived since childhood, would be some kind of secret location. Leaning in for the kiss, Xavier makes Moira good on her promise and wipes her mind clean — control freak to the end. She goes back to the CIA a blank slate, prompting McCone to file her back to her original place: “This is why the CIA is no place for a woman,” he sighs, as Erik, now Magneto, arrives to retrieve Emma from the CIA’s secret prison (which, for some reason, is located at their headquarters at Langley). “[Xavier’s departure] left a bit of a gap in life, if I’m to be honest,” he says to Emma, “I was rather hoping you would fill it.” Perhaps he’s speaking to Emma as a telepath, perhaps he’s speaking to her as a romantic interest, remembering her use as a sexual surrogate between him and Xavier, in this way becoming his own version of the two-timing Shaw.

The credits, kicking in, recall the Maurice Binder titles that made the James Bond movies distinct pop-art artifacts, even as Magneto’s cape and re-painted helmet signal the beginning of a new concept. X-Men: First Class, with its script that easily bests any half-dozen of the Bond movies’, even on their home turf, that is, in their cultural synthesis of the Cold War, makes its own case for pop-culture evolution: the better-adapted screenplay survives.

The parts where the characters get their nicknames seemed very forced. Especially when Beast gets his. He’s just suffered a horribly traumatic transformation, he may look like a monster for the rest of his life, and Havoc immediately starts calling him Beast. Makes Havoc seem like a total dick.

I don’t know that much about Havok, but he seems comfortable being thought of as a total dick.

It’s been pointed out that Xavier relies on his mind-control for his effectiveness as a speaker and persuader. Which is why, when Erik had the helmet on, he said precisely the wrong thing.

They’ll never find Charles Xavier, who’s hiding IN HIS HOUSE.

Oops — I now see you touched on that. Will increase font size.

Hiding in his house, in a wheelchair, paralyzed. Quite the conundrum for the world’s most advanced intelligence network.

This, alas, is where history and First Class diverge.

Why “alas”? One of the main points of this exercise was to explain when and how that divergence happened — as it must, for us to get from a world where there are a few mutants but nobody knows about them, to a world where mutation is common, known, and a focal point of conflict. For that shift to be a satisfying story, the mutants have to interfere now and change the course of history. Is it only that, by changing things, the movie steps away from the points of commentary that have been salted throughout?

(How Shaw managed to keep a grip on his nuclear reactor as his submarine flew, crashed, broke apart and rolled over is not explained.)

My impression is that his control over energy includes kinetic energy. In that case, he could buffer himself quite easily. (Which may or may not be a question and answer the writers consciously thought about; however, it works as an explanation.)

Erik’s response, “Never again,” of course, is the motto of the western conscience

Not just the western conscience generally, but I believe of Israel specifically. Which makes Erik turning the missiles on the ships a comment on Israel’s defense policies, particularly with regard to Gaza.

I say “alas” only because the narrative had done such a good job of fusing history and fantasy up to that point.

I don’t think it entirely stopped (witness the “following orders”/”never again”) exchange, but I also don’t think the timeline divergence is necessarily to blame for the shift. It has as much or more to do with the fact that the story shifts into a more action-oriented mode, which leaves fewer openings for political commentary.

The last thirty minutes of the movie are entirely great, mind you.

Oh, I’m not complaining! There may not be any historical commentary in Xavier direclty experiencing Shaw’s death, or Erik deflecting the bullet into Xavier’s back, but both of those are powerful moments.

Well, when you introduce fantastic characters into real-world historic events, you have basically two options: The Masquerade, or Out of the Closet. The former is the place of ancient conspiracies guiding world events, but replace the Illuminati, the Freemasons, and the Bilderberg Group with vampires, aliens, wizards, or mutants. The latter is the default of most superhero comics post-Watchmen (and even a few before). By the time of Singer’s X-Men films, the existence of mutants is widely known and feared by most normal humans. It makes sense for the prequel to start setting the stage for both public knowledge of mutants, and the fear of them.

I truly feel like the shift from real to imagined history probably is best viewed as one of those things people started to suspect the government covered up or lied about. First Class is also sort of a “declassification” if you don’t mind the pun.

What I remember most about this movie is how shocked I was when the bullet hit Xavier. And then seconds later, I thought “Oh, of course, because he has to end up in the wheelchair.” X-Men was probably the first modern superhero comic I read, I read it faithfully for years, and this movie made me forget that Xavier was going to be injured and end up in a wheelchair. I’ve had conversations with friends similarly well versed in the X-Men’s history and they had pretty much the same experience. With Erik, I knew what was coming and hoped that somehow it wouldn’t. With Xavier, I was taken by surprise in a way I never expected to be.

I’m not much of an X-Men x-pert, so I never knew why Xavier was in a wheelchair, but I loved how the movie presented him as vital, hirsute and rangy, then took all that away, because it succeeds in making him tragic — he lived life at a remove because his sense of superiority, now he’s forced to do the same because of his paralysis.

The comic book reasons for his paralysis are very different from the movie version, more complicated and with less emotional resonance. So it wasn’t so much that I didn’t see the particular circumstances coming as that I momentarily forgot that the movie was going to have to put Charles in a wheelchair before the end credits.

“I loved how the movie presented him as vital, hirsute and rangy, then took all that away…”

I like your use of “hirsute” there, and how we have foreknowledge that Professor X will be bald in the future. I imagine an alternate ending when, instead of Magneto accidentally causing a bullet to hit Xavier, Magneto causes a giant bottle of hair remover to land on Xavier’s head.

“Hiding in his house, in a wheelchair, paralyzed. Quite the conundrum for the world’s most advanced intelligence network.”

Well, Xavier does have amazing psychic powers…

I was a bit disappointed they decided to end with Xavier in the wheelchair. Mostly because as Todd has been saying, the Xavier/Magneto relationship is the heart and soul of this film and it was sold wonderfully by McAvoy and Fassbender, I really wanted to see it carry on into at least another movie.

”Lift that sub” might be my new favorite euphemism. So Erik refuses to be bottom to Xavier’s control-freak top.

(It takes a certain kind of top not to think, why would this yellow uniform not be the color of choice for the Holocaust survivor? For a telepath, Xavier doesn’t do a great job of putting himself in other people’s shoes to understand their position, only to control them. In that sense, the use of the Russian officer is totally consistent with his failures to think about other people’s consequences.)

Unrelated, it’s a curious effective reversal to make us know all about the war (there isn’t one), and the missiles launched at the mutants (they’re going to survive, they’re major characters in later films that sort of try to keep consistent), but surprise us with a single bullet that cripples Xavier. (There are so many versions of his origin story that even real comic nerds might not see that one coming.)

One of the greatest things about this screenplay is how it makes Xavier so very powerful about getting inside people’s minds, and yet so not empathetic. He tells Erik a number of times “I know everything about you,” but he hasn’t stopped for a moment to actually look at life from Erik’s point of view. He’s too convinced of his own rightness.

Also, curious that Erik has a pseudo-father in Shaw and a lost mother to drive him on; while Xavier also has a not-there mother (that probably drives him on in his early womanizing ways), but no father figure.

So they both become fathers with their adopted mutant families, Erik clearly following in the abusive footsteps of Shaw. But Xavier’s paternalism–where does that come from? Is that ever touched on in the film? Or in the absence of a single father, is Xavier’s paternalism just based on his class (in the socio-economic sense)?

Lastly, I enjoy the film, but still get a little confused by Erik’s tragic fall: he fails in his first encounter with the sub, but after Xavier teaches him love, he’s able to (nudge, nudge) lift the sub at the end. So is the trauma of the past just something that can’t be overcome in the long run? Or is there some misunderstanding about love in Charles’s groovy mindset?

There’s a beat where Raven says “Professor Xavier, I like that” and he says something about how he needs students before he can be a professor, as though having students is the last thing on his mind. On the one hand, his paternalism is there from the beginning, even when he’s a child, but on the other hand he just wants to get attention and get laid, he doesn’t want to lead. It’s his pursuit of Shaw that puts him in the position of having to lead.

Excellent note about lifting the submarine. Of couse, back when this movie takes place a boy would often ask a girl if she wanted to go down to the river to watch the submarine races.

Erik’s encounter with Shaw might have turned out differently if Xavier had been with him, instead of inside Shaw’s brain, but the beats are laid out in perfect tragedy: Shaw will kill Erik with his awesome nuclear power and kill everyone else as well, if Xavier stops controlling his mind. Shaw must die or he will kill everyone, and he almost convinces Erik that he (Shaw) was correct all along. Erik kills Shaw not just out of revenge for his mother, but because on some level he knows that Shaw is right, and has been right all along. He thinks he’s killing the Shaw part of himself, but of course he’s just perpetuating Shaw’s evil. It’s quite brilliant, I think.

Did you ever see the fan-made ’60s style opening credits for XMFC? http://vimeo.com/m/21905044

Very nice, although these folks went for the Saul Bass route.

anyone else notice jennifer lawrence’s excellent performance in the shear act of appearing completely uncomfortable with herself throughout the movie? save for her time with hank and the scenes with the young mutants all getting to know each other, she looks like she never knows what to do with herself, and by the beginning of the last act, as she’s coming into her own, her uniform clashes completely with her body, hair and movement. raven’s heart certainly is the battleground of charles’ and eric’s romance, and lawrence does a damn good job of expressing mystique’s agency in those rare moments she gets to be herself, gradually flirting with eric’s ideas and constructing her own model of self-love. in a few ways, she comes out ahead of both charles and eric, both of whom can only find themselves effecting change globally, while she, ever the postmodernist, focuses first on herself.