The Avengers part 2

At the end of the last post I mentioned “stakes.” An important thing to understand about stakes is that they are directly related to the success of a cinematic narrative. When the stakes are low, the movie feels “small,” and the narrative decreases audience involvement. A movie about a guy who loses his keys is going to be less involving, to most people, than a movie about the end of the world. On a macro scale, less audience involvement generally means less audience. When the stakes are life-or-death, audience involvement increases. So The Avengers takes care to mention, right up front, that nothing less than the fate of all humanity, and the universe, is at stake. Not the planet, not the solar system or even the galaxy, but the universe. Obviously, this movie is playing for keeps.

Who is in the helicopter in the picture above, and where are they going in such a hurry? “Helicopter,” in a thriller setting, is usually a shorthand for “government.” Only the most powerful people get around by helicopter. This dates back to the war in Vietnam, where American helicopters rained death on a civilian population for years. The helicopter, cinematically speaking, became a symbol of oppressive authority.

But in this case, “helicopter” means human, as opposed to the creepy alien dudes we’ve seen in the movie so far. So a helicopter, while still a symbol of power and authority, is downright cuddly in the context of this narrative. Whoever is in that helicopter, we know he’s powerful, very powerful, and we also know that he’s human.

Where is the helicopter going? The helicopter is going to some sort of government installation, The Joint Dark Energy Something. What’s happening at the Joint Dark Energy Something is that everybody there is getting the hell out. This, in screenwriting, is called “getting into the scene as late as possible.” We don’t know what everyone is running from, we only know that they are running. This, too, increases audience involvement. The audience leans forward to gather information when they are not spoon-fed it by a cautious narrative. We don’t even get a clear look at the sign. Do we need to know exactly what this place is? Not really — the sheer size of it, which we’ve seen from our helicopter’s POV, is enough to indicate that it is “important,” and the panic erupting all over is enough to indicate that it is in great danger. Again, stakes. “Important” and “Great Danger.” Concision.

Everyone at the Joint Dark Energy Something is in a panic, except this guy, this guy who’s there to greet the helicopter. This guy is, Marvel fans will know, Agent Coulson, beloved agent of SHIELD. But to the viewer who just wandered in from off the street, all we know is that he is The One Guy Who Isn’t Running Around Panicked. That makes him very powerful in his own right, and the fact that he is waiting for the helicopter makes whoever is in the helicopter that much more powerful. Keep in mind, we’re still only a minute or so into the movie — if nothing else, The Avengers is a sleek deliverer of information. We’ve not only been given a ton of information, we’ve been given it in a highly cinematic style.

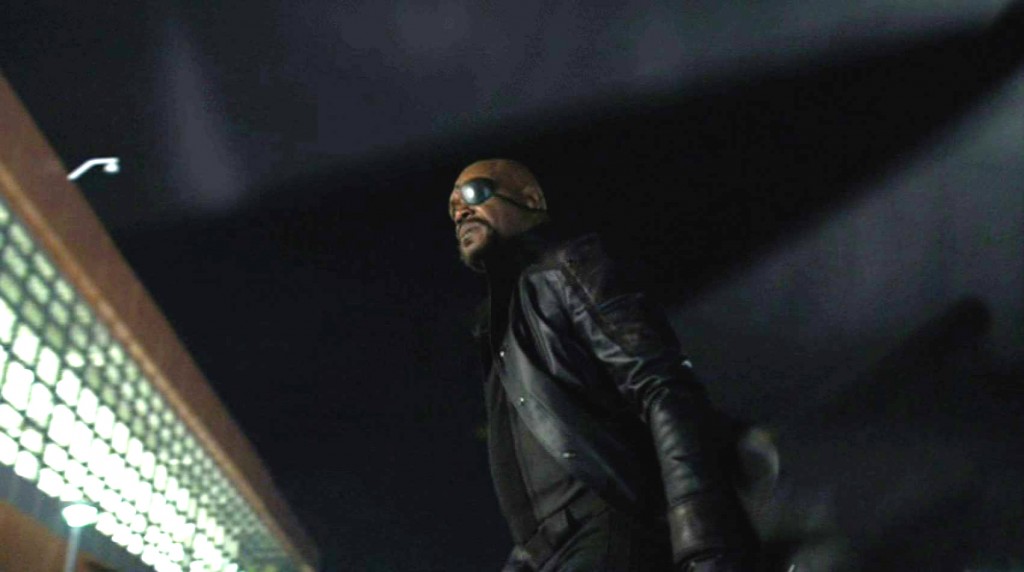

And finally, after an exhausting two minutes of movie, we meet our protagonist, Nick Fury, getting out of the helicopter. This is the powerful man in the helicopter, this is the man The Only Man Not Panicking is waiting for. Everyone else is Running Away, this man is Walking Toward. You don’t need to know anything else, he hasn’t opened his mouth, he hasn’t introduced himself, all he’s done is fly in in a helicopter and get out, and already you know he’s very important and very powerful.

(Technically, the true protagonist of The Avengers, is, of course, whoever is on the other end of the celestial jukebox that Mr. Bigrobe is talking to. This turns out, eventually, to be a guy named Thanos, and Mr. Bigrobe turns out to be a guy named, er, “The Other.” The “protagonist” of a story, the way the Greeks used the term anyway, was the guy who set events into motion. Thanos wants The Tesseract, The Other sends Loki [the “ally”] and The Chitauri to get the Tesseract, and it falls to Nick Fury to stop those guys from doing that. This, technically, makes Nick Fury the antagonist of The Avengers. To make this distinction seems picayune, but, in fact, this protagonist problem is why so many superhero movies suck — it is inherent in the genre that the protagonist of the narrative is the bad guy. The moment you have a main character whose job it is to run around stopping things from happening, you have a reactive protagonist, which means a weaker narrative. When you have a weaker narrative, you end up throwing all kinds of nonsense at the screen, hoping that no one will notice that you have a reactive protagonist. This is, incidentally, why Batman barely even shows up in Christopher Nolan’s Batman movies — he understood that the protagonist of his Batman movies had to be Bruce Wayne, not Batman, and that, for his narratives to succeed, the bad guys had to be reacting to the actions of Bruce Wayne, not Batman reacting to the actions of the bad guys.)

What is it about superhero movies that requires a bad-guy protagonist? Is it that so often the superhero’s goal is to ‘save the world’ – and there had darn well better be something worth saving it from – or something else?

As soon as the guy puts on a cape, the narrative moves into the realm of the fantastic. If a guy has superpowers, he’s either going to use them to beat people up, which would make him a supervillain, or he’s going to use them to help out, which makes him a hero. A hero who’s “helping out” with nothing else to do isn’t an interesting protagonist.

This is, of course, the problem with James Bond movies as well, and it’s why we speak of “James Bond Movies” as a separate entity from “movies.” They have their own rules. James Bond, if left to his own devices, would drink and gamble and sleep around. You have to present to him a threat to the entire world before he’ll do anything.

Very interesting point about reactive protagonists.

As someone currently studying ancient Greek literature, I’m not entirely sure your point about protagonists always being the guy/gal setting things in motion held true then any more than it does now.

Sure Oedipus is aggressively trying to find out who murdered so and so, but he is really only the detective trying to solve the case; he didn’t set everything in motion (although actually thinking about it I suppose Oedipus the King is one of the very few dramas in which the main character is both the protagonist and the antagonist… ). Odysseus is trying to get home, that works. The Iliad is trickier – Achilles is the protagonist but he spends 5/6 of the piece crying in a tent; he’s barely a reactive protagonist (I’ve yet to see Troy, I’d be interested to see how they deal with that, I imagine they get Brad Pitt doing a lot more). In other tragedies, although the protagonist is always trying to achieve something that is the plot, very often they’re only reacting to something other characters have set in motion. Medea is getting revenge on Jason, but only because before the play begins he has left her for a princess, etc.

So really, I don’t think the Greeks had a figured out any better than writers of drama do now – they had their reactive and proactive protagonists, too, and their dramas suffered just as much if the protagonists were reactive. The Odyssey is a far more compelling narrative because of Odysseus’ simple goal and active protagonisting, whereas the Iliad can be pretty hard going. And of course, there’s the whole thing that our superhero stuff is just another version of all that Greek gods/epic heroes stuff…

Your understanding of Greek drama outstrips mine. I got that tidbit of information from McKee, but perhaps it was all Greek to me.

Troy starts well before Achilles begins sulking, divides its attention enough that it doesn’t feel jarring when we switch to other stuff while he *is* sulking, and then ties everything off much more tidily at the end than either the Iliad or the Trojan War story as a whole does (e.g. Agamemnon doesn’t go home and get killed by Aegisthus; he gets taken care of in the film itself). Plus, it puts the entire thing — not just Achilles’ hissy fit but the whole war — on a much shorter timeline, sans gods.

I actually liked it a fair bit. The narrative is significantly changed, but mostly in ways that serve the purpose of making it a functional story in its own right, rather than a faithful adaptation of the stories it’s based on.

Nice points about how efficiently the film establishes the importance of Coulson and Fury.

Regarding stakes: audience involvement can also drop when the stakes are big, but impersonal. That’s why it works better to have Loki, a character familiar to several of the protagonists, be the agent of Thanos, and why Fury does his whole gambit with Coulson’s death, and why so much of the film’s success (I think) hinges on getting the audience to enjoy the characters’ interactions even before those characters get personally invested in saving the world. One of the failure modes of superhero stories is that the Universe Is At Stake, but I don’t have any reason to care.

Word.

The discussion about “stakes” at the beginning here seems simplistic. Are your remarks confined to certain kinds of genres? To the extent I’ve thought about this, stakes play a tricky role in movies and it’s far more subtle than “bigger is better”. Something I thought was ridiculous about the first Sherlock Holmes movie was how outsized the stakes got in comparison to the setting. How do we understand the effectiveness of movies like The Talented Mr. Ripley, whose stakes are hard to pin down but are certainly piddling in comparison to those in The Avengers? I just saw Life of Pi, where the stakes feel real and are the source of real tension perhaps because the “universe” is vastly contracted, yet that tension somehow comes regardless of the fact we know the protagonist lives through the ordeal, and still exist even after some spoilery complications later on. This is all to say, I don’t see that the idea of a movie about a guy losing his keys is necessarily less involving than Battlefield Earth.

The stakes in Talented Mr. Ripley don’t involve the fate of the universe, but they do involve the deaths of several people, and the absolute corrosion of Ripley’s soul.

Whatever the scale of the narrative, the stakes have to be as high as possible. And to be a successful drama, the lives of the characters have to be utterly changed by the pursuit of those stakes.

Take a romantic comedy: the stakes are, generally speaking, “true love,” which are stakes uppermost on the mind of everyone in the audience. Falling in love is probably the most powerful experience a person can have, and while the stakes are not life-or-death, they certainly feel like it at the time.

In Life of Pi, the stakes are huge — the boy must figure out how to survive with a freaking tiger in his lifeboat. The lifeboat is his whole world, and there’s a freaking tiger in it.

The problem with the movie about the guy losing his keys is reversibility. If the guy spends two hours looking for his keys, then decides he’ll just use his spare set, there’s no real reversibility. If, on the other hand, the guy loses his keys and sets off on a journey that eventually takes him all through his world and changes everything in his life, now you’ve got an effective drama. If he can’t find his keys and one of the keys is the key that gets into the safe-deposit box that holds the device that will stop the evil computer from destroying the world, now you’ve got a genre picture.

Thanks a bunch for the reply. I see your point about reversibility. I guess I’m hung up on the first part of the sentence “Whatever the scale of the narrative, the stakes have to be as high as possible.” Why not take a romantic comedy and simply expand the scale so there’s more room for higher stakes? Why not graft onto Silver Linings Playbook a subplot about a hitman trying to kill the protagonists? Or why not put even more people’s lives at stake than there were in Talented Mr. Ripley? Obviously at some point this gets ridiculous. But how do you characterize that aspect of a story that would work against an attempt to raise the stakes? Alternately, fidelity to the comic books aside, why not rework Avengers into a story of superheroes combating an evil corporation (threatening to kill a lot people or something)? I feel like our entry into a movie is how we relate to the characters. From that perspective, what practical difference does it make whether the stakes are the universe or merely millions of people?

“The universe” does seem like overkill, doesn’t it? After all, no one apart from quantum physicists really cares about “the universe,” people care about people. And animals. To make the stakes the universe signals, I think, that there’s a level of The Avengers that acknowledges that it’s kind of silly.

When I mean that the stakes need to be as high as possible, of course I mean as high as possible within the confines of the story’s genre. If you put a hitman into Silver Linings Playbook it’s no longer a character-based drama. If you put Loki into The Godfather it’s no longer a tragedy. Tom Ripley could kill more people (he certainly kills his fair share) but Talented Mr. Ripley is a dark drama about class and the corrosion of a man’s soul, not a horror movie.

I just saw the Hobbit and immediately thought of this post, because in my opinion the reason the Hobbit feels so dull and overly long is that it has virtually no stakes. It tries to keep with the apocalyptic feel of the stake-filled lord of the rings (the world will end if the ring isn’t destroyed) while only having “us dwarves miss home” as the drive, and actually if the adventure stopped nothing would actually happen.

That’s the “reversibility” thing I discuss above. If Bilbo says “Actually, I’m quite comfortable here, thanks,” what happens? If the answer is “nothing much,” you have poor drama on your hands.

I think a reason the villain is the protagonist in super hero movies, is they tend to be set in the real world (more or less). And since the real world isn’t run by a super villain, the villain has to have some scheme to take over the world, or something similar, and the hero has to react.

You could fix this by having the movie set in a world that is already run by someone evil. Then the hero would be the protagonist, going up against the established system. Only story I can think of that does this is V for Vendetta.

One could also do this if one has the hero fight some real world evil. A guy gets superpowers and decided to fight to make North Korea a democracy.

There are, of course, plenty of movies about individuals fighting a corrupt system, but they’re a comparative rarity in the comics-based movie landscape. Batman Begins comes to mind, at least the first hour of it, and perhaps The Punisher. But again, when the fantastic elements are introduced, like a bizarre plan to destroy Gotham City by microwaving its water supply, it’s no longer drama, it’s action.