McCartney, part 3, in which I try to quantify greatness, so that I may dissect it

If you will bear with me a moment, I’m going to attempt a syllogism, or at least a mathematical formula:

IF we say that the recordings of the Beatles represent a certain extremely-high standard of professionalism, creativity and musical success,

AND Paul McCartney was one-fourth of the personnel of the Beatles,

AND said McCartney was one-half of the writing team responsible for most of the Beatles songs, that gives us SIX PARTS of responsibility, of which McCartney may reasonably lay claim to TWO, or ONE THIRD.

THEREFORE, ONE THIRD of solo McCartney material, post-Beatles, and absent other Beatles, may reasonably be expected to reach the same level of professionalism, creativity and musical success.

Does McCartney meet the demands of this (arbitrary, unfair) formulation? Do the other Beatles? Could anyone?

Let’s take a closer look at the Beatles’ recordings. They are all masterpieces. I can say this because the best definition I’ve ever heard of “masterpiece” is that a masterpiece is an artwork that we can return to again and again throughout a lifetime and always get something new from it. I’ve been listening to the Beatles recordings probably since before I could write words, and I haven’t gotten close to getting to the bottom of their mysteries and surprises.

What do they do? How do they work? What are the hallmarks of “Beatles recordings,” that make them stand out from all other recordings? To stick with the theme of this blog, what do the Beatles’ recordings want?

I am not a musicologist. One could write a book on why the Beatles’ recordings work musically, and more than one person has. I am, however, a dramatist, and I find that my primary response to the Beatles recordings is dramatic. They have an overwhelming sense of drama, each song a perfectly realized little world, each recording existing by its own rules, often with an arrangement utterly unique: even if it’s just guitars, bass and drums, somehow each time a new sonic aspect of those instruments are teased out.

It’s almost as though every time the Beatles entered the recording studio, they acted as though they had never entered a recording studio before, and didn’t know if they would ever get the chance again. There’s an incredible make-or-break sensibility to each recording, in the same way there’s a make-or-break sensibility to Raging Bull. Every corner of every song is packed with melody, invention and what I like to call “entertainment value.” There’s never a wasted moment or dull stretch in a Beatles song, even “Revolution 9.”

Think of the urgency of the Beatles songs. They did not come here to waste your time, and they will not let you change the station. A casual glance through my Beatles CDs tells me that many Beatles songs begin with the chorus, or sometimes don’t even have a proper chorus, or rather are all chorus, with bridges in between choruses. Many of the songs in question not only begin with the chorus, they don’t even have introductions, they just begin. I counted twenty-eight (out of roughly 200 Lennon/McCartney Beatle tracks) that begin with the vocalist plunging into the chorus without any introduction at all. Think of a sonic avalanche like “She Loves You,” a song both insistent and distant, joyful and pejorative, delivering someone else’s good news in a way that makes you assume that she couldn’t really love anyone but the singer. If McCartney is this happy about telling you that she loves you, just think of how happy he would be if she loved him.

Check out these examples of the finest dramatic writing in pop music. These are all the first lines of Beatles songs, sung without any introduction whatsoever, often a capella.

“As I write this letter, send my love to you –“

“Close your eyes and I’ll kiss you, tomorrow I’ll miss you — “

“If I fell in love with you, would you promise to be true — ?”

“Try and see it my way, maybe time will tell if I am right or I am wrong — “

“You tell lies thinkin’ I can’t see, you can’t cry ‘cos you’re laughing at me, I’m down.”

“Ahh, look at all the lonely people — “

“To lead a better life — “

“In the town where I was born, lived a man who sailed to sea — “

“Hey Jude, don’t make it bad — “

“The long and winding road that leads to your door — “

“She came in through the bathroom window — “

And my personal favorite, which begins in the middle of the phrase —

“For I have got another girl — “

Think of that! McCartney begins the song in the middle of a phrase!

For the purpose of comparison, here are the opening lines of some Shakespeare plays, pulled off my shelf entirely at random:

“Who’s there?”

“When shall we three meet again?”

“Tush! Never tell me!”

“I thought the king had more affected the Duke of Albany than Cornwall.”

This is masterly drama, beginning the song, the “argument” as it were, in the middle, forcing the audient to “catch up” with the singer. Each one of these opening lines is immediately arresting, plunging us into a drama already in progress — who could fast-forward past a song that begins, a cappella, “For I have got — ” for he has got what? Oh, another girl, I see — and why does he have another girl? What was wrong with the first girl? Why would a Beatle need another girl? And when are we going to get back around to the first part of that phrase? “I ain’t no fool and I don’t take what I don’t want, for I have got another girl,” ah yes, there it is.

You could say that these are simple pop songs, but they are not simple pop songs. Even the Beatles’ earliest recordings have a complexity and experimentalism that remains striking today. Just the other day I was driving with my 4-year-old daughter Kit and 1962’s “There’s a Place” came on, a song I don’t think I’ve ever sat down and listened to. Kit responded to it immediately and demanded to listen to it nineteen times in a row, allowing me a chance to get to know what was, to me, essentially a “new” Lennon-McCartney song. After I got used to the perfectly bizarre harmonics of Lennon and McCartney’s twin vocals, I started working out the lyrics in my head. “There’s a place,” they sing, “where I can go,when I feel low, when I feel blue, and it’s my mind, and there’s no time, when I’m alone.” The next verse starts “I think of you, and things you do,” which makes me think that “when I’m alone” attaches grammatically to the second verse, but it also works as the last line of the first. There’s a place where the singer can go when he’s depressed, and it’s his mind, but there’s no time when he’s alone. Meaning either that the singer could be happy in his mind if he had time to be alone, or else he must retreat into his mind because he’s never alone. Either way he’s completely miserable, and either reading is surprising in what sounds like a chirpy pop song on first listen. And this is before Beatlemania made John Lennon officially miserable, two years before “I’m a Loser” and three years before “Help!” (incidentally, both those songs also begin with a cappella choruses too).

They manage to do all of this while sounding like the most joyful people on earth. Paul McCartney sings “I Saw Her Standing There” like a dying cancer patient who’s suddenly been given a clean bill of health. All the vistas of life have suddenly opened for him. (“Well she was just seventeen, you know what I mean” also happens to be one of the great couplets in songwriting history and a perfect example of Lennon-McCartney teamwork — as McCartney tells the story, the opening couplet was originally “Well she was just seventeen, she never was a beauty queen,” but Lennon either substituted the existing line or pressured McCartney into changing it, turning it from a comment on the subject to thrusting the subject into the mind of the listener.) There is an incredible immediacy to the Beatles recordings, a sense that something is happening, right now, as the tape is rolling. This in spite of their mature recordings sometimes taking days or even weeks to painstakingly record and edit.

“You know what I mean” reminds me that, like any great songwriters, the Beatles are notable not just for all the musical detail they put into their recordings, but also for what lyrical details they leave out. Their songs often come almost to the point of cohering, only to back off at the last moment, creating not so much a story but a moment, not a drama but a scene, leaving out the beginning and the end, leaving the listener to finish the narrative his- or herself.

Which brings me to my last point, the Beatles talent for collage. Starting with the Sgt Pepper concept (which, despite the album’s greatness, isn’t very well fleshed out), most notably in “A Day in the Life,” but continuing through the jarring juxtapositions of the White Album and, most notably, on Abbey Road, the Beatles in their mature phase (which I think it’s safe to say is when McCartney came into his own, shouldering the lion’s share of the production burden) (and being the biggest asshole) threw out all the “love song” mainstays that had made their reputation and instead turned to crafting sonic landscapes with lyrics that were impressionistic, nonsensical or even completely meaningless. Side Two of Abbey Road only sounds incredible, none of those songs would have made it on their own, it’s only when “Mean Mr. Mustard” bumps into “Polythene Pam,” which then comes crashing into “She Came In Through the Bathroom Window” that the songs gain their sense of excitement. These juxtapositions are related to montage, just as “shot of gun,” “shot of woman screaming,” “shot of man falling down” are uninflected images stitched together to form the dramatic beat of “man getting shot.”. That is to say, again, the primary impact of these recordings is dramatic.

So, if we say that the criteria for a good “Beatles recording” includes a heightened, almost supernatural sense of urgency, immediacy, complexity and experimentalism, a dramatic force and alacrity, performed joyfully, uniquely arranged and containing melodies both absurdly catchy and built to sustain generations of scrutiny, we might then be able to move on to judging McCartney’s work after the Beatles, and how it compares to the work of his bandmates.

McCartney, part 2, in which I relate a brief personal history

.jpg)

My response to the life and work of Paul McCartney is complex and contridictory. Where to begin?

Perhaps the thing to do is to find an orientation point. Where did I begin?

In the summer of 1973 my brother and I were in our bedroom in the suburbs of Chicago playing Battleship and listening to Top-40 radio on WLS. Just imagine what kind of songs might have been playing on Top-40 radio in the summer of 1973. I suggest you imagine them because I can’t remember a single one. “Benny and the Jets?” I’m out.

Anyway, in the midst of all this, a song came on. It was a weird, haunting lament with a keening vocal that sounded like nothing else on the radio. The opening was odd enough, but about two minutes into the song this weird thing happened. There was this sound, like a jet engine revving up, but still musical, a big rushing, orgasmic whoosh. It got more and more intense and my brother and I stopped playing Battleship and stared at the radio. What the hell was this sound coming out of it?

Just when it seemed that our little transistor radio could no longer contain the sound coming out of it, the big whooshing sound stopped and suddenly a different song was playing. This song was completely different from the song before the whooshing, sung by a different singer, with a different tempo to it. Then, just as soon as you got used to this new song, it suddenly got weird and colorful again, the orchestra coming back in with a big apocalyptic pronouncement. Then, just when you thought the song was going to freak out again, suddenly that first song was back again, now with a little faster tempo. I had no idea what the guy was singing about but I knew I wanted to know what would happen next.

After one more verse, that whooshing orchestra came back, whooshing and whooshing, surging and climaxing again, until the whole thing ended on a triumphal shout of trumpet. Then, silence, heart-stopping silence. Then, a massive, perfect, world-ending piano chord that went on for about six seconds before the radio announcer came in and started talking about whatever bullshit he had to talk about at that moment, while that monolithic piano chord slowly decayed in the background.

And my brother and I just sat there staring at the radio. I was twelve years old.

My brother and I listened to WLS for days afterward, waiting, hoping, wading through the Jacksons and the Osmonds and Jethro Tull and whoever else was popular at the time, waiting for them to play that weird, heart-stopping thing again. What the hell was it?

Then, finally, days or weeks later, it came on again. My brother heard it first and ran and got me and we sat there on his bed listening, transfixed, again, trying to take it all in, failing to do so.

This time, as the final piano chord decayed, the DJ came on and said, and I remember so clearly, “W…L…S. A Day in the Life. The Beatles!” then went on to describe some contest they were having that weekend.

“A Day in the Life.” The Beatles. At that moment I knew what I wanted for my birthday. I had no idea who the Beatles were, really, where they came from or what they stood for, but I knew that I had to own that recording.

And so, for my thirteenth birthday, my brother got me The Beatles 1967-1970. It was the first album I ever owned and I still have that copy. I unwrapped it, took it to the stereo, sought out “A Day in the Life,” and dropped the needle. And there it was again. Now I owned it. This weird, inexplicable slice of heart-stopping, life-giving psychedelia was now mine to keep, an experience that I could relive any time I pleased.

After listening to “A Day in the Life” a few more times, I decided to take a chance on hearing what else was on the record. I picked up the needle and started at the beginning. Here are the songs that came on, one right after the other: “Strawberry Fields Forever,” “Penny Lane,” “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” “With a Little Help From My Friends,” “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds,” “A Day in the Life” and “All You Need is Love.”

Now then. I was not a hermit, I was a thirteen-year-old boy growing up in the Midwest, driving in cars and shopping in stores. Of course I had heard all those songs a million times on the radio. But get this: I had no idea they were all recorded by the same people. I wasn’t even sure at that point what music was, who created it or why it existed, it was just something that came out of the radio, I had no idea how it got there. And yet here were all these great songs, each one of those recordings is its own 3-minute world of sounds and sensations and references. And that was just one side of a two-record set! It took me weeks to get through that album, listening to sides over and over again, trying to soak it all up, all the melody, all the weirdness, all the joy, all the deep messages, (well, deep for a 13-year-old Midwestern boy) all the invention and wit and innovation. It didn’t seem possible — four men in their twenties made all this music?

Like everyone who encounters the Beatles, I soon chose one as my favorite. And my favorite was immediately Paul. I knew that it was John who sang most of “A Day in the Life,” but the John parts of “A Day in the Life” weren’t what sold me on the song, it was that the song changed in the middle into a different song, this one sung by Paul, and the resulting drama, and the bookending orchestral flourishes, were what made the song such and experience.

(And you could say “Well, but it’s still John’s song, he could have had all those ideas,” and yet when we look at the work of both men in the ensuing years, who is the one who, time after time, found ways to take little bits of nonsense and fluff and weld them together in startling and dramatic ways, resulting in pop suites where the whole was immeasurably more than the sum of their parts?)

And I loved “I Am the Walrus” and “Revolution” and “Come Together,” but none of them could hold a candle to “Hey Jude.” Here was a song that somehow struck at one’s heart before the first piano chord had finished playing. How did McCartney do that? He sings “Hey” a cappella, and as the answering piano chord comes in under him singing “Jude,” you’re already hooked, you’ll listen to that song for seven minutes, three and a half of it repeated coda, and wish it went on longer. How did he do that? His songs were always these volcanic outpourings of generosity. Even a trifle like “Hello Goodbye” builds with an amazing sense of drama, then resolves, then tosses in a joyous coda. The sound of the piano on “Lady Madonna,” the fat sound of the brass on that recording, the propulsive beat, the speaking-directly-to-the-vain, misunderstood-13-year-old-boy “Fool on the Hill,” the hilarious “Back in the USSR,” a Chuck Berry/Beach Boys parody that managed to blow both of them out of the water, The Beatles 1967-1970 was a watershed in my life, a lodestar, a portal to a world I could live in and never tire of.

Over the next five years I slowly acquired all the Beatles albums (my family didn’t have much money at the time) and listened to nothing else. In 1978 my mother died after a long illness and I bought my first Rolling Stones album — I was ready to see what other music there might be out there.

In due time I became an authentic disenfranchised angry young man. I repudiated Paul and his uncanny sense of craft and polish and became a die-hard John fan. Still later, I would come to admire McCartney’s sense of craft and become skeptical of John’s reliance on shock and experimentation for its own sake. Now I don’t know what the hell to think. John was bound to lose this contest, since he’s been incapable of creating music for the past twenty-seven years, but that’s a subject for another day.

Paul McCartney I

I’ve been thinking a lot about Paul McCartney, what with his new record out, with its valedictory feel, and all. McCartney is a subject of longstanding fascination, fandom, frustration and exasperation around my household, so much so that it’s hard to know where to begin. For every moment of genius in his work (about sixteen million or so) there seems to be an equal number of missteps, squanderings of talent, outright atrocities and failures of character, and I’d like to take the time to sort it all out in the next few days.

But here’s a good place to start:

So we were listening to the Beatles on the way to Target the other day, chatting about this and that, and their recording of “Long Tall Sally” came on, featuring McCartney’s joyful, electrifying, vocal-cord-shredding singing, the only serious challenge to Little Richard’s ownership of this song ever attempted. And Kit, 4, in the back seat of the Prius, started getting really excited. “Mom! Mom!” she said. “This is what I wanted my ukelele to sound like!” Kit’s mom explained that she had earlier in the week expressed dissatisfaction with the sound of her ukelele, despite the time spent tuning it. Little did she realize that Kit wasn’t looking for tuning, she was looking for electricity, and of course, the propulsion of John Lennon playing it.

I could probably tell a personal story or two about every single Beatles song in existence, but this incident struck me. We had been driving in the car listening to the Beatles for about twenty minutes at that point, and songs like “You Won’t See Me” and “Hello Goodbye” had played. In fact, McCartney’s very “Long Tall Sally”-esque “I’m Down” had just played moments earlier, and Kit hadn’t batted an eyelash. What was it about the recording of “Long Tall Sally” that had captured Kit’s ear? What quality did that recording have that produced the shock of recognition, the sudden realization that this is what she wanted her music to sound like? She didn’t want it to sound like “Nowhere Man” or “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” or “All Together Now” (three of the most requested tunes on my iPod), she wanted it to sound like “Long Tall Sally.” (This is the child who picked, of all things, 1963’s “There’s a Place” as the song to listen to 19 times in a row while we were recently stuck in traffic.) All the songs we’d been listening to featured electric guitars, and most of them featured McCartney singing. Did Kit sense, on some level, that McCartney singing a Little Richard song in front of Lennon and Harrison’s guitar (and Ringo’s drums, of course — that’s the only thing my kids really understand about the Beatles is that Ringo plays the drums) produced an alchemy that the other songs did not? And what is that alchemy? Why was the startling, shattering “I’m Down” pleasant enough, but “Long Tall Sally” a life-changing experience?

Guido Nielsen

I have harbored an interest in ragtime music since, well, probably since seeing The Sting at age 11, and it has always frustrated me that any recording of ragtime I could find always sounded like it was recorded at the bottom of a well or else obscenely tarted-up, “cutified” to appeal to popular tastes (like, um, like the soundtrack to The Sting, for instance).

So when I stumbled across Guido Nielsen’s Scott Joplin: The Complete Rags, Marches, Waltzes and Songs at my local used record store, with a handsome package designed by no less an entity (and ragtime authority) than Chris Ware, I snapped it up.

The recordings are revelatory. Nielsen’s performances are clear-eyed, unadorned and unsentimental, letting the the compositions speak for themselves, and the recording is state-of-the-art in its clarity and precision. Impossible to listen to without experiencing overwhelming feelings of giddiness, optimism and joy, while still feeling the deep strains of melencholy and even tragedy that inform some of the melodies. This music is American life itself.

I enjoyed the set so much I sought out Nielsen’s recordings of two lesser-known Joplin disciples, Joseph F. Lamb and James Scott, again abetted by the lovingly lavish Chris Ware designs. They do not disappoint.

Mr. Nielsen hails from Amsterdam (figures, no American musician would treat his nation’s musical legacy with such respect and devotion), and emerges from the Beau Hunks Sextette, which has recorded definitive versions of Raymond Scott tunes and music from Little Rascals shorts. I recommend them all, especially Manhattan Minuet, which is one of my favorite recordings of all time and also features smashing design from Chris Ware.

Elvis vs. Elvis

These two songs came up on iTunes today, two of my favorite music stars ever, illustrating two approaches to writing songs about women.

Elvis C’s description of his subject is bitter, multi-layered, multi-dimensional and hyper-literate:

“So you began to recognize the well-dressed man that everybody loves

It started when you chopped off all the fingers on your pony skin gloves

Then you cut a hole out where your love-light used to shine

Your tears of pleasure equal measure crocodile and brine

You tried to laugh it all off saying “I knew all the time…

But it’s starting to come to me”

— Elvis Costello, “Starting to Come to Me”

While Elvis P’s view is more practical, topical and down-to-earth.

“And when I pick up a sandwich to munch

A crunch-a-crunchity-a-crunchity-crunch

I never ever get to finish my lunch

Because there’s always bound to be a bunch of girls”

Elvis Presley, “Girls! Girls! Girls!”

Long Live the King

Today, January 8, is Elvis Presley’s birthday. He would have been 72.

When people learn I am an Elvis specialist, they often ask me, “Did Elvis Presley make any good movies?”

The answer, sadly, is no. Elvis Presley did not make any good movies.

There are, however, good Elvis Presley movies.

Elvis Presley made 31 feature films between 1957 and 1969 and, by any objective measure, they’re all terrible. Elvis movies, like James Bond movies, Star Trek movies, Bollywood musicals, Italian zombie movies and Japanese horror movies, cannot be enjoyed if compared to other “real” movies. They’re horrible. They’re beyond horrible. They’re stupid, boring and comically inept. You watch an Elvis movie and you can’t believe people went to see them, three times a year, for ten years. You watch an Elvis Presley movie and you can’t believe Elvis Presley was ever a star, much less the most important American artist of the twentieth century. You watch an Elvis movie and it seems unbelievable that Elvis was, when his film career began, the biggest star on the planet. You watch an Elvis movie and you have to remind yourself that these movies were made at the same time as Dr. Strangelove, West Side Story, Persona, Lawrence of Arabia, Jules et Jim, Bullitt, 2001: A Space Odyssey and Bonnie and Clyde, not to mention A Hard Day’s Night, Help! and Yellow Submarine. The biggest star on the planet couldn’t get a decent movie made around him to save his life. And as a result, he became no longer the biggest star on the planet.

There are a lot of reasons for this, which I can go into another time. Hint: they have to do with Col. Tom Parker being an evil, evil man.

For us Elvis fans, the movies’ flaws only make them more endearing. If you take them on their own terms, if you approach them with the same level of expectation you would have for, say, an episode of Here’s Lucy, they are perfectly engaging. As a chapter in Elvis’s career, they are an important step in his development as an artist — that is to say, they gave him twelve years of unbelievably crappy songs to sing so that he could “come back” in 1968.

THE WELL-INTENTIONED GENRE PIECES

Cineasts will say that King Creole, which co-stars Walter Matthau and is directed by Michael Curtiz, qualifies as a “good” Elvis Presley movie. But they are wrong. King Creole is a middling noir which, for some reason, stars Elvis Presley. Elvis tried to make a number of “real” movies, that is, movies that “just happened” to star Elvis Presley. These include Love Me Tender, a Civil War drama, Wild in the Country, a “juvenile delinquent” drama written by Barton Fink himself, Clifford Odets, and Flaming Star, a western drama, starring Elvis as a half-breed, directed by Don Siegel. It’s impossible to enjoy these movies as genre pieces because, well, because Elvis Presley is in them. He’s not believable as a cowhand, a half-breed or a down-on-his-luck kid. First, he’s not a very talented actor, second, he throws off charisma like a 1,000,000-watt lightbulb, blasting character, plot and every other actor offscreen (or into irrelevance). So you’ll have a couple of actors sitting around talking, pretending they’re in a “real movie,” and then ELVIS PRESLEY walks in and any sense of watching a “real movie” goes right out the window. It doesn’t get any better when he starts singing; there’s no reason why these movies would need to have singing in them at all (they were all developed as dramas — King Creole was originally about a boxer who gets into trouble with the mob [that is to say, it was originally a boxing movie]) –songs were shoehorned into existing scripts and it shows.

Of these four, King Creole has the best songs — that is, real Elvis Presley songs, not cringe-inducing novelty numbers (which sprout in abundance later, as we will see). The title song is a smash and the movie also includes “Hard Headed Woman, “Trouble” and “Crawfish.”

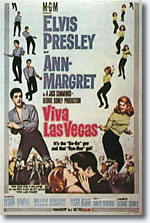

THE CREAM OF THE CROP

This is it. This is the best Hollywood could do. These three movies have it all. Elvis plays someone very much like himself, so there isn’t that awkward Elvis/reality schism. He sings, all-in-all, wonderful songs opposite real actors. He explodes off the screen. He is sexy, hot-headed, dynamic, graceful and bursting with energy. The direction and editing have zazz and pluck. In Viva Las Vegas, he even stars opposite a woman who can hold the screen with him. They are superlative entertainments and, more importantly, they are excellent showcases for Elvis’s talent. Viva Las Vegas also gets a gold star for being the one “Elvis Movie” that shows that the whole idea of an “Elvis Movie” can work as entertainment.

By “Elvis Movie” I’m speaking of a classically stupid, unbelievable, nonsensical concept that exists simply as an excuse for Elvis to sing, do something “exciting” (usually in front of obvious rear-screen projection) and kiss pretty girls. In the case of Viva, for instance, Elvis is a singing race-car driver who has to choose between wooing Ann-Margret and winning the big race. See? You wouldn’t go to see that movie. That’s a stupid idea for a movie. It is, in fact, a retarded idea for a movie. Imagine, if you will, George Clooney starring as a singing race-car driver who must choose between wooing Ann-Margret and winning the big race. You couldn’t get that movie made today. But it makes perfect sense as an Elvis Presley movie and is the model for the genre. The soundtrack also includes “You’re the Boss,” a number cut from the movie, that sounds astonishingly like Elvis singing on a Tom Waits record.

THE BIG-BUDGET ELVIS MOVIES

These movies are all professionally made, make no sense, are produced by Hal Wallis, made money and do what they’re supposed to do. I hate them. They are boring, pedestrian, and exist to make Elvis Presley “safe” for middle-class America.

There is a thing that happens in Elvis movies, where the composers can’t be bothered to come up with an original song so they re-purpose a copyright-free song and write new words to it. In Blue Hawaii it’s “Alouetta.” In another one it’s “Three Blind Mice.”

Girls! Girls! Girls! features “Song of the Shrimp,” where Elvis sings the tale of a shrimp who longs to climb aboard a shrimp boat to see the legendary land of Louisiana. All four of these movies include lullabies, and/or songs sung to mothers.

MY PERSONAL FAVORITES

You always love your retarded children more than the others. Producers other than Hal Wallis discovered that you could make more money with a cheap Elvis movie than you could with an expensive Elvis movie. And this accounts for the bulk of the Elvis filmography, what I like to think of as the “real” Elvis movies. They have the texture of Formica, the depth of cellophane and the complexity of a gallon of buttermilk. They don’t feel like movies at all, they feel like episodic television. This week on Elvis, Elvis is caught behind the Iron Curtain and must match wits with batty spies in order to get to his big singing gig! They are uniformly genial, sporadically charming and cinematically dead on arrival.

In each one Elvis plays a singing racecar-driver/speedboat-driver/cliff-diver/helicopter-pilot/boxer/hillbilly who has to win the race or win the big fight or solve the mystery. In Tickle Me he has to hunt for buried treasure in an abandoned western town which may or may not be haunted. Four decades of Scooby-Doo adventures have robbed this movie of much of its surprise.

Novelty songs abound, and I pretty much adore every song from every one of these movies. Girl Happy has the best of them, a charming number called “Fort Lauderdale Chamber of Commerce.” (yes, you read that right.) Paradise Hawaiian Style features “A Dog’s Life,” which is sung to, who else, a helicopter full of dogs, and also “Queenie Wahini’s Papaya.” Fun in Aculpulco has “No Room to Rhumba in a Sportscar.” Tickle Me, the cheapest of the movies, actually benefits from not having any “new” songs for Elvis to sing. Instead, he gets to sing some actual blues numbers from his post-army years, and one is actually reminded for a moment that he is one of the most significant American talents of all time.

It Happened at the World’s Fair includes a cameo by the young Kurt Russell, who plays a snot-nosed brat who kicks Elvis in the shin. It also contains the only intentionally funny joke in the Elvis filmography: Elvis walks down a street by himself, flips through his “little black book,” looking up a girl who lives nearby. He finds her name and recites “Mary. Hmm. 36-24 — pause — Maple Street.” He then cocks his eyebrows and moves on.

Clambake holds a special place in my heart. It represents what may possibly be the nadir of Elvis’s personal life. He had put on thirty pounds or so, was taking spiritual advice from his barber, and had cracked his head open on a sink the night before shooting began during one of his adventures in pharmacology. As a result, his hair is combed into permanent, shellacked bangs and the belted leisure suits he wears make him look like Ubu Roi. It also features the worst song, bar none, of his career, a “High Hopes” knockoff called “Confidence,” which he sings to a playground full of kids. Now, keep in mind that, ten years earlier, Elvis Presley was enraging parents, scandalizing censors and making teenage girls go weak in the knees. Now he’s singing to children about building confidence. It’s an obscenity. I love it.

THE ALSO RANS

What does it say about a movie when it just isn’t quite as good as a low-budget Elvis movie? And yet, these movies, for whatever reason, don’t make the cut. Easy Come, Easy Go, in spite of being a Hal Wallis production, is a stupefying atrocity, where Elvis, no kidding, plays a singing scuba diver who must battle evil hippies in order to find sunken treasure. Live a Little, Love a Little is a Mad Ave comedy that co-stars Rudy Vallee and features a “psychedelic” number, “Edge of Reality,” where Elvis sings to a man in a Great Dane costume. Frankie and Johnny is a period piece which should, theoretically, give Elvis a chance to explore the roots of his music, but which does not.

MUST TO AVOID

Harum Scarum isn’t just a bad Elvis movie, it’s one of the worst movies ever made by anyone. Agonizingly boring, impossible to sit through, full of crappy songs, cheap sets, bored actors, nonexistent editing and uninspired writing and direction. Stay Away, Joe, in addition to having perhaps the worst title of any Elvis movie (they might as well have called it Stay Away, Audience), features Elvis, I could not invent this, singing a song to an impotent bull.

THE LATE EXPERIMENTS

Late in his film career, Elvis abruptly stopped making “Elvis Movies” and returned to trying to make “real” movies. Charro! is a Clint Eastwood western without songs, The Trouble With Girls is a bizarre, unwieldly, Altmanesque portrait of life on the Chatauqua circuit circa 1929, and Change of Habit is an urban “problem drama” with Elvis starring as a ghetto doctor who falls in love with a nun. The nun (Mary Tyler Moore) must choose between Jesus and Elvis.

They all suck, although Change of Habit does hold the viewer in a certain stateof ghastly fascination.

My iPod is drunk again

I have over 11,000 songs on my iPod and it is set permanently to shuffle. If I’m not mistaken, that means that each time a song ends, the chances of any other song coming up is at least 1 in 11,000. And yet, in the past 30 minutes my iPod has played four David Bowie songs, all from Diamond Dogs. Diamond Dogs!

This happens every few weeks. Not Diamond Dogs necessarily, but something. It will play the same song twice in an hour, or a long string of Elvis Costello, or a whole hour of depressing, nostalgic songs pining for home and times gone by and lost love. It went on a Leonard Cohen kick one afternoon and I had to shut it down and re-start it before it would play anything else.

Rolling Stones, Dodger Stadium 11/22/06

They can’t get no.

I can no longer say that I have not seen the Rolling Stones in concert.

Partly I was motivated to attend this show out of generational duty: I don’t want my grandchilden to one day say to me “What, you were on the planet at the same time as the Rolling Stones and you never went to see them?” Partly, I was curious as to how a group of multimillionaire sexagenarians (emphasis on sex, tee hee) could possibly get up on an enormous stage in a huge stadium in front of tens of thousands of people and play songs where they rail against the establishment, pine from unrequited love, celebrate substance abuse, loose women, serial murder and Satanic worship, and, of course, complain about a lack of satisfaction in their lives. What could such a show possibly mean?

Turns out, they sidestep the question of sincerity by their mere presence. Sure, they’re singing songs of sex and drugs and rock-n-roll written by twenty-five-year-olds, but they’re singing them here and now, old men, performing with the energy and enthusiasm of men half their age. They can’t possibly mean hedonist, sybarite songs like “Honky Tonk Women” or “Sympathy for the Devil” — what they’re celebrating is their ability to keep performing anything at all. But sweet hopping Jesus do they perform, and with great authority and abandon. More than once my wife cringed, worrying that Mick Jagger was bound to pop a knee joint or slip off the stage. There was not a trace of boredom, rote performance or forced bonhomie on stage. When Mick went into a wild, spastic dance that sent him jittering across the stage, it wasn’t “part of the act,” it was what he genuinely felt like doing at that moment. And we cheer and sing along not because we worship the devil or get crazy on drugs every night, but because we are inspired by the Stones’ refusal to stop playing.

And you know, they’re not just enthusiastic, they’re humble. The Stones weren’t just glad to be there tonight (Keith thanked his brain surgeon, who happened to be in the audience), they were genuinely humbled that so many people were nice enough to come out to see them. Mick would sing a song about getting high or a woman torturing him through her indifference and then say something to the audience like “What a nice group of people you are tonight.” They went through a terrific, drawn-out version of “Midnight Rambler” and right after Mick threatened to “stick a knife right down your throat,” he politely thanked the audience for their patience (the show got started late, after having been moved from Saturday because of Mick’s throat infection) and then actually apologized for the traffic. It kind of undercut the whole menacing-serial-killer vibe, but like I say, menace didn’t really seem to be the point of the show.

Even though they’re in a stadium, tiny figures on a gigantic stage, they perform as though they are in an intimate club playing for the hell of it. There is very little spectacle in the show and the emphasis is on music, the, god help me, subtle interplay of guitars and drums and band camaraderie. They blow notes, goof around, crash into each other. There’s nothing flashy on stage to distract from mistakes, the sound is sometimes muddy and there are no apologies made for fluffing. To solidify the “club” atmosphere there is a section of the show where the middle of the stage breaks off and moves slowly from center field to home plate, and suddenly the biggest band in the world is playing on a tiny stage in a sea of faces, careening around and grinning like idiots.

This evening they played two songs from their new record. Otherwise, there was nothing from after 1983 (“She Was Hot”) and very little from after 1974 (“It’s Only Rock n Roll”). That means 22 years of their discography was completely ignored, and yet they still found 20 or so terrific songs to play, not a dud in the bunch, and not to walk through but to genuinely play, play like they would honestly not rather be doing anything else at that moment.

Early on, Bonnie Raitt came out to sing a verse of “Dead Flowers” and I remember thinking “Gee, you know, if that was your only hit song, you’d still have a pretty impressive career,” but it was probably one of the least well-known songs of the evening. (“Dead Flowers” is also one of the few songs that sounds better as the singer gets older — when Mick was 30 he was being snide and ironic, now he sounds sincere and sadder-but-wiser.)

So, Mick might no longer feel as though he has been crowned with a spike right through his head, and he may no longer see a red door and want it painted black, and he may no longer feel that it’s absolutely necessary to call him the tumbling dice. But he and the others have found a way to keep playing those songs after 40 years and still make the performance mean something, even if the meaning is mainly in the act of performance itself. The songs celebrate bad behavior, loose morals and throwing one’s life away, but their performance celebrates perseverance, longevity and a life well-lived.

Tower Records, RIP

Tower Records has gone bankrupt, been sold, and will be liquidated.

I could write a bunch of stuff about what this indicates about recent shifts in the music business, how Tower’s “deep stocking” policy no longer makes sense in an era where musicphiles can get pretty much anything they want with a few mouseclicks, and worry about what this means for brick-and-mortar music stores in general.

But my initial response is a personal one.

Moving from southern Illinois to New York in 1983, I had, quite literally, never seen anything like Tower Records on Broadway and 4th St. A record store that took up an entire city block? Three stories of it? Unbelievable. Records I had only dreamed of owning were on sale here every day from 9am to midnight, 365 days a year. That’s right, Christmas and New Year’s included. If, on Christmas morning, I suddenly felt the need to own The Minutemen’s Double Nickels on the Dime (maybe because I didn’t get it for Christmas) I could saunter right over and purchase it.

From the moment I saw that store, I vowed that this was the locus solus of the New York experience. My first home was in a far-flung corner of Park Slope, but each year I moved closer to my goal, until finally, in 1999, I was able to afford a loft on Broadway, a half-block away from Tower. An evening’s meditative walk for me would start at Tower Records, move on to Tower Video (and Tower Books, upstairs) when it was across the street on Lafayette, with perhaps a side-trip to Other Music if I was in the market for an Other Music kind of record, then on to St. Mark’s place where I would check to see if any of the new releases I was interested in could be found for used prices. If I was feeling expansive, up to Virgin on Union Square and then, if it wasn’t too late, the Strand. Then, often, I would end up circling back to Tower before heading home.

When I became interested in “downtown” music in the late 80s, your John Zorns and Elliott Sharps, before the Knitting Factory had their fancy digs and their own label, Tower was often the only place those records were available. And they were open late enough that you could see a band at a club (or a Philip Glass concert at BAM), dash right over and buy their record before the place closed (and the urge to purchase wore off).

When I began working in Los Angeles, I found myself overwhelmed, as many are, by the sprawling, anonymous quality of much of this kudzu-like metropolis. I would center myself and get my bearings by visiting the Sunset Blvd store. I used to say that if I ever became a fugitive from justice, the authorities would always be able to find me by staking out Tower Records on a Tuesday afternoon.

I have too many memories of joyous discoveries and artistic connections made in the aisles of Tower to list here, but here’s one that comes to mind as emblematic. On the morning of 9/11, like everyone else in New York, I stood transfixed in my living room watching the horrifying images unfolding on TV (even though they were happening a mere 1.5 miles away). The only thing that interrupted my morning was going downstairs to Tower — hey, it was new releases day, with not only the new Bob Dylan (“Love and Theft”) but also the new Leonard Cohen (Ten New Songs). It was 9:30 or so and neither building had collapsed yet. The aisles were filled with sobbing, wailing office workers, unable to watch the images being broadcast on the monitors lining the first floor, and unable to look away. The street outside was filled with a tide of humanity walking uptown, all the subways being shut down and no cabs available. In the coming days, when Manhattan was shut down south of 14th St, lower Broadway became an eerie, empty pedestrian mall, but Tower remained open.

“She Loves You:” a closer look

Above: the young McCartney, pale and drawn, haunted by his recent encounter, and the ensuing recording. Is the awkward pose a kind of code? And why are the other Beatles obviously distancing themselves from McCartney? Are they worried about possible sniper fire?

Below: the young woman in question.

______________________________________________________________

Your ex-girlfriend has a message for you. The message is, “She loves you.”

And you know that can’t be bad.

Can’t it?

Let us consider.

It is 1963. You are, presumably, a teenage boy, although the song does not specify age or sex. The point is, you have an ex-girlfriend and she says she loves you.

The question becomes: Who is your ex-girlfriend?

Your ex-girlfriend is, apparently, a person of considerable power and influence. How do we know this? We know this because Paul McCartney is her messenger boy.

McCartney, one of the most celebrated young men in the United Kingdom at this point, has recently been in contact with your ex-girlfriend and she has impressed upon him the overwhelming, urgent nature of her message, which is that she loves you. Not only is McCartney impressed, but he is sufficiently terrified of the repercussions of his failure to deliver this message that he has enlisted the aid of his band The Beatles, overwhelmingly the most popular and influential musical act in the UK, to assist him with this message delivery. McCartney, you see, apparently does not know you personally, nor does he know where to find you. All he knows is that your ex-girlfriend has a message for you and it is his urgent need to deliver this message.

And so McCartney has used every ounce of his compositional talent to craft a bombastic, hysterical football-chant of a song, immediate in its impact and devastating in its catchiness, and has enlisted The Beatles to play it, and on top of that has enlisted the aid of Parlophone records to distribute the recording to every record store in the nation, and Swan records in the United States (and, when their distribution capabilities prove inadequate, Capitol). Every radio station in the English-speaking world will be pressed into service to play it, and The Beatles will even sing a version in German on the off-chance that the message might reach you in Deutschland as well. On top of that, The Beatles, leaving no stone unturned, will eventually visit every civilized nation in the world (and Indonesia), playing this song in concerts before millions of listeners, and will continue to do so for three years, in a marathon attempt to deliver this message to you.

That’s some ex-girlfriend.

Who is she? How did she come to wield such power and influence? Why didn’t McCartney simply say to her “I’m sorry luv, I’m a rather busy pop star and this, frankly, seems to be a private matter?” What methods did she use to impress upon him the overwhelming importance of her love, so that he would spend the next three years of his life delivering the message, through recordings and live performance, to every possible recipient in the hope of reaching you? Your ex-girlfriend, it seems, has an iron grip on the attention of Mr. McCartney.

I think we have to allow the possibility that your ex-girlfriend is unstable and possibly dangerous.

What suggests this? Let’s examine the primary evidence, the message itself.

“You think you’ve lost your love, well I saw her yesterday, it’s you she’s thinking of, and she told me what to say.”

Seems simple enough. Let’s move on.

“She says you hurt her so, she almost lost her mind.”

Okay, let’s stop right there.

Your ex-girlfriend has instructed Mr. McCartney to write in his message to you that she has “almost lost her mind.” What kind of declaration of love is that? “Please come back to me, I’M NOT CRAZY.” This passage speaks volumes.

Now let’s go back to that first line. “You think you’ve lost your love.” Why were you trying to lose your love? What makes you think you’ve succeeded in losing your love? How intense were your efforts, and how diligent has she been in following you? And consider the subtext of McCartney’s desperation: “You think you’ve lost your love, well I saw her yesterday.” What he’s telling you is “You think you’ve lost your love, well, she she was able to get to me, Paul McCartney, the biggest celebrity in the UK, a man of considerable power and influence. What chance do you think you stand of avoiding her? Give it up, for the love of God, talk to her, PLEASE, TALK TO HER.”

And “I saw her yesterday.” Apparently she can get to him any time she wants. Note how in every performance of this song, and McCartney must’ve racked up thousands by now, he still sings “Well I saw her yesterday.” She is, for years, in near constant contact with one of the most heavily guarded personalities of his time. This ex-girlfriend, obviously, has her ways of getting to people, and does not give up easily.

(“Yesterday.” There’s that word, a word that would haunt McCartney for the rest of his life. He saw your ex-girlfriend yesterday; is it only coincidence that yesterday is the same day that so shattered him, that saw him reduced to “not half the man [he] used to be?” There’s “a shadow hanging over me” — a troubling image we will examine the implications of later.)

“But now she says she knows your not the hurting kind.” This line could be read a number of ways. Either your ex-girlfriend is confident in her abilities to overpower you physically (Why not? She’s got Paul McCartney wrapped around her little finger) or else she’s whistling in the dark. You have disappeared, fled this dangerous, unstable young woman, in fear for your life, and in her desperation she has crafted a fiction about the nature of your personality. “Come back, I know you didn’t mean to hurt me, I understand completely and I love you, and I won’t let Paul McCartney out of my clutches until you respond in kind, in order to prove my point.” What could this possibly be except the actions of a crazy person?

(In German! They recorded a version in German! Why? Has your ex-girlfriend expressed a concern that you perhaps have amnesia, and are living in Germany? Does she think, perhaps, that some German-speaking friends or relatives might relay the message to you? What evidence does she have of this? Does she think that, in your desperate avoidance, you have fled the country, changed your name and taken up speaking a foreign language? What the hell did this young woman do to you?)

“Although it’s up to you, I think it’s only fair.” Yes, that’s right, it’s totally up to you. Please don’t let me, Paul McCartney, biggest pop star in the UK, influence your decision in any way, it’s absolutely your decision to make. HOWEVER: “Pride can hurt you too.” Ah, there’s the rub. It’s utterly your decision to make, but YOU WILL FEEL THE PAIN OF THAT DECISION.”

“Apologize to her.” Oh, now wait, what the hell? I thought the message is that she loves you, now she’s demanding an apology? Not herself, of course, no, that’s not her style. No, it’s McCartney, McCartney is pleading with you, please, for the love of God, apologize to her, or you will find yourself in a world of pain. This is no tender declaration of love, this is a plain-spoken threat.

“And with a love like that, you know you should be glad.” Yes, you should be. But McCartney, at this point, is fooling no one. Look at the way certain phrases are repeated, chantlike, over and over — “She loves you, yeah yeah yeah,” “and you know that can’t be bad,” “and you know you should be glad.” This is what Shakespeare referred to as “protesting too much.”

An image forms in my mind. The Beatles return from a world tour, exhausted and terrified from their international mission of message delivery. A pale, drawn, shaken McCartney returns home to London, thinking he’s fulfilled his duty, but is greeted at his door by your ex-girlfriend.

The rain pours down, wetting the young composer’s hair as he stands, crestfallen at the sight of the trembling, enraged young woman. “Did you deliver the message?” She asks. “What was the reply?”

McCartney has no answer. Distractedly, he fumbles with a cigarette. He can’t get a match to strike, not in this sodden English weather. “I didn’t hear back,” he stammers, “I did my best. Please, you have to understand –“

“You didn’t even locate the recipient, did you?” she cuts him off. McCartney goes pale. The cigarette, soaked and lifeless, trembles in his lips. He knows that he will have to go back to the other Beatles and insist that they tour the world once again, enduring constant threat to their lives, in the service of this young woman. It’s going to be another long year.

(Did McCartney, perhaps, actually die in 1966, as was widely rumored? Was it at the hands of your ex-girlfriend?)

More important, perhaps: who are you? What did you do to this young woman, who must be a middle-aged woman by now, if she’s still alive? Are you still alive, or did you pay for your relationship with this young woman with your life? When will it be safe for you to come out of hiding? Are you waiting for another message from McCartney, a song whose chorus goes “It’s all right, she’s dead, you’re in the clear?” What will it take to heal this wound? Can your ex-girlfriend ever be satisfied?

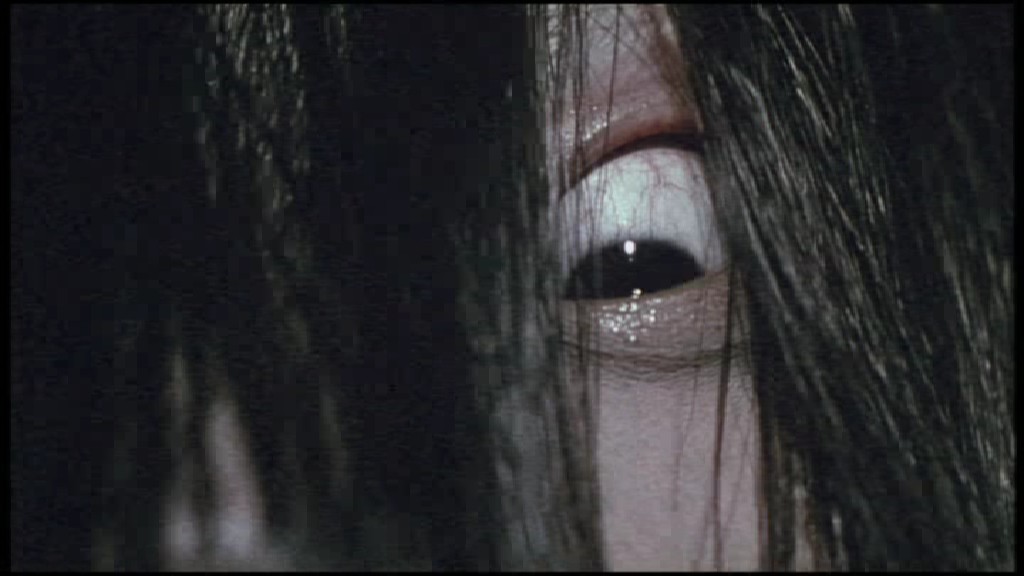

Let’s face it, in the end there is only one possibility: your ex-girlfriend is a supernatural being of terrible power. Your ex-girlfriend may be, in fact, not your ex-girlfriend at all. The song does not, after all, identify her as an ex-girlfriend, merely that she is female, that you “hurt her so,” and that she loves you. She could be your daughter, your sister or even your mother. You may not even be aware of her existence, but she loves you and her love is powerful, constant and unstoppable. She could, in fact, be a ghost and, like Sadako in Hideo Nakata’s Ringu films, she will never rest until her message has been disseminated to every living person on the planet. Which begs the question: what did you do to her? You “hurt her so.” As per Sadako, did you push her down a well because of her awesome powers of destruction?

Whoever she is and whatever her powers, her mark on McCartney was permanent and irreversible. In three short years, she turned him and the other Beatles from cheeky, entertaining moptops to sallow bickering, paranoid drug addicts. What else explains the Beatles’ withdrawl from public life, their investigations into psychedelia and escape into hallucinations, John Lennon’s relationship with the Sadako-like Yoko Ono, George Harrison’s obsession with spiritual life?

What will free the world from the curse of her “love?”