Hit her, baby, one more time

In response to yesterday’s post, Anonymous writes —

“Why would Britney”… is already the wrong approach and question. Why do you see an individual reasoning? This is no play. “Britney”, as one can see from Moore’s film, is an idiot, in the real sense of the word. Really, nothing personal, she is. How many interviews and subsequent white-trashtastic failures does it take to show over the YEARS, the chances to prove after her mother-managed first years that she understood anything, are gone. We talk about a “poor” girl who is rumoured to make 700thou a MONTH without doing anything. Such is the sublime banality of the U.S. media culture.

This comment interests me. Anonymous’s anger here is palpable, and reflects some of the strong feelings I’ve been hearing about Ms. Spears’s attempted comeback (including another long piece in the New York Times today). Any artist who makes people this angry must be worthy of some kind of attention.

So let’s examine this comment a little more closely.

Spears’s individuality, in Anonymous’s opinion, hinges on the fact of her supposed idiocy. If I’m reading this correctly, what Anonymous seems to be saying is that Britney is too stupid to have a successful career on her own, that she has been managed and packaged and handled and promoted and, if left to her own devices, would be unable to string two words together or feed herself properly.

Well, let me just say that I have no problem with that. I don’t demand that artists be scholars, or even particularly bright. I don’t care if they are drooling morons, as long as they have something to contribute to our culture. Elvis Presley had trouble with food, drugs and sex, Frank Sinatra was an alcoholic, woman-beating psychopath, Chuck Berry was a pathetic degenerate and Jerry Lee Lewis married his 13-year-old cousin. None of these guys would ever make it at the Algonquin round table, but each one of them is a sublime, significant American artist.

So what is eating Anonymous? Spears’s “idiocy” is related, in the poster’s mind, to her “white-trashtastic failures.” So it’s a class thing then perhaps, Anonymous is upset not because a pop-star is a failure, but because she is betraying her “class.” I personally don’t know Spears’s background so I don’t know if she’s reverting to her white-trash roots or not. But let’s bring up Elvis again, since Spears decided to the other night it seems fair game. Elvis Presley was renowned for what Anonymous would call “white-trashtastic failures.” In Elvis’s mind, he was always and forever a white-trash truck-driver who got lucky, and his subsequent actions reflect that. He had terrible taste in clothes, food and manners, and behaved in the most garish, uncouth and barbaric ways, so much so that, by the end of his life, his personal tastes had completely overshadowed his substantial musical legacy. So I, for one, am still unconvinced by Anonymous’s argument — I don’t need my artists to be refined sophisticates any more than I need them to be scholars.

Next, Anonymous is outraged by Spears’s alleged income. This I can reject out of hand — you sing a super-hit song, you get millions of dollars. That’s the way it goes. I may like the song, I may not (and in the case of Spears, I couldn’t even hum it for you), but if people bought her music, she deserves the money. Lots of popular artists make art I don’t cotton to that other people do — I see nothing wrong here.

But now, Anonymous’s argument gets interesting. “The sublime banality of the US media culture.” Ah, so, it’s a national problem — Spears is a symptom of some sort of larger national disgrace.

Anonymous has, I think, hit on something here. We here in the US have been living through six years of utter bullshit, not unlike the England of Orwell’s 1984. We have been told, day after day, for six years, things that everyone can plainly see are untrue. This has produced a kind of national nausea, we’re like a nation of abused children being ruled by bullies who want to punch anybody who wears glasses, and a media culture who will snigger along with the bullies as they beat up the nerds and laugh at all their pranks. We know the Bush administration was wrong in their response to 9/11, we know they lied to us about Iraq, we know they abused the darkest moment of our recent national history in the most cynical and heartless way possible to gut our constitution and ransack our national treasury. We took five years of that and then elected a Democratic congress, who has, so far, done precisely nothing that we asked them to do. We, as a people, feel powerless and bitterly, bitterly frustrated after six years of being ruled by cruel, brutal monsters who are aware of every moment of our agony and laugh to each other about it, slap each other on the back and say “Heckuva job.”

We feel like we can’t do anything about Bush or the media who writes down every stupid lie he utters as though it is truth and common sense. We can, however, do something about Britney Spears, who, as Anonymous says, is, like Bush, an idiot, a puppet controlled by a machine, raking in cash, promoted by our national media, made famous for her embarrassing “white-trash” pratfalls while the rest of us suffer. We can’t get Bush out of office, but we can destroy the career of Britney Spears.

I must admit, I was baffled by the Times headline today — “Spears’s Awards Fiasco Stirs Speculation About Her Future.” I thought, really? Speculation about her future? From who? Why? Who cares? Why is this in the New York Times?

And I realized, this isn’t about Spears at all, this is about Bush, or rather, it is about our national health. Spears, we have decided, no longer deserves the fame and wealth we heaped upon her — she has betrayed us. Given the perfect context and opportunity for a “comeback,” she flubbed it — took the TV time and the money, stumbled as badly through her routine as Bush stumbles through a simple declarative English sentence, and said “now give me my career back.” We’ve had six years of this bullshit and we’re not going to take it any more.

(The timing could not have been worse, putting on this non-show so close to the anniversary of 9/11, and with the Petraeus testimony looming the next day. We as a nation were at our highest level of shame, disgust and anger toward our elected officials that night. What if Spears had triumphed? She could have truly “come back” in the Elvis sense, been a truly popular artist who does what a truly popular (that is, “of the people”) artist does — she could have taken the anxieties, hopes and dreams of a nation and crystallized them into a pure pop moment of power, hope and, sure, why not, sex — man, what a show that would have been! Why, that would have been like Elvis Presley getting his act together and proving himself for his Christmas special in — what year was that again? oh yeah, 1968, the high-water year of Vietnam and the year the entire world rioted. See, that’s what was riding on Elvis in 68, that’s why he closed the show with “If I Can Dream” — his message was “Hey, World, I pulled it together, I lost the weight, I regained my focus, and I deeply care — why can’t you?”)

What was the name of Spears’s song on Sunday? Oh yes — “Gimme More” — the chant of the Bush administration. Why wasn’t the song called “Four More Years?” Britney demanded more, just as Bush has demanded more — more of the middle-class’s money, more of the poor’s children, more of our national dignity, all without giving us anything in return. We cannot rebel against a grinning moron who controls the courts, the Congress and the media, but by gum we can certainly rebel against a stumbling buffoon who demands that we watch a lame, three-minute dance routine. Not to sound too much like the hysterical young man now, doubtless, famous on Youtube for his impassioned defense, but I suspect that Britney is now dying for the sins of Bush.

If you’re looking for trouble…

It is not the goal of this journal to engage in cheap gossip. However, it has come to my attention that Britney Spears has, apparently intentionally, crossed over into an area of my interest.

I know almost nothing about Britney Spears, except that she was a music star a while back and has since gone on to a career in gossip headlines. Her appearance the other night at MTV’s VMAs was front-page news on, of all things, The New York Times, which got my attention, but when one of my favorite comics bloggers Occasional Superheroine devoted a column to it, I had to see what all the fuss was about.

First, I know nothing about the music of Britney Spears, except that she probably doesn’t make enough of it. It seems to me, if everyone talks about you being washed up, the answer to that is to work more. Maybe the work will suck, maybe it won’t, maybe it will take you in strange new directions, but if you don’t go away sooner or later they have to take you seriously. If Bob Dylan or Elvis Costello or Madonna packed it up every time critics said they sucked, our musical landscape would have a much different shape today.

So okay, maybe Britney Spears doesn’t have that kind of ambition or talent. So fine. But then, here she is, making her “comeback.” Now then, the thing about “comebacks?” You don’t call it a “comeback.” You don’t get to decide you’re making a “comeback,” it’s for other people to say when you’ve made a “comeback.”

Now then: Ms. Spears, for reasons that utterly baffle me, chose for her “comeback” appearance an homage/parody/whatever to the opening of Elvis Presley’s ’68 Comeback Special (and please note that the ’68 Comeback Special was originally known as something like “Singer Presents Elvis” or some other godawful corporate title). She has cleverly changed the words of “Trouble” to the words from “Woman” (both songs were written by Leiber and Stoller, and have the same melodies).

(I, for one, do not criticize Ms. Spears for gaining weight. If “hotness” is what she was after, she looked plenty “hot” to me (although her spangled bikini did not seem to fit her well). HOWEVER, if you’re going to go out on stage like that, perhaps it’s best not to open with a song that contains the lyrics “I can bring home the bacon, fry it up in a pan.” Because all I could think of after that was “And then eat it.”)

The question is, WHY, oh why, would Britney Spears choose to honor/parody/whatever one of the true diamond-hard everlasting moments of Pop Greatness for her “comeback?” The “Trouble/Guitar Man” number at the top of the ’68 Comeback Special is still electrifying and flabbergasting 40 years later — and Britney Spears makes a deliberate allusion to it, hoping to compare herself to — what now? Elvis? Twelve years after he changed the face of American culture, ten years after being drafted, eight years after starting his string of never-ending soul-crushing movies? Britney is inviting us to compare her years in the wilderness to that?

All would have been forgiven, of course, if she had then delivered. But she did not. Her performance of the number is abysmal — she shuffles around the stage as though she just woke up, not bothering to lip-sync, much less sing, pacing through the dance routines as though practicing in front of the TV instead of performing in front of millions of viewers.

Anyway, there’s my two cents.

to make you cry

I’m reading Lynn Hirschberg’s long profile of music producer Rick Rubin. I like Rick Rubin — who doesn’t like Rick Rubin? — and I am surprised to learn that he’s crossing to the other side of the desk and becoming a record-company executive. No, not a record-company executive, the record-company executive, co-president of Columbia Records. Columbia Records! Jiminy!

Anyway, the article is a great read and a fascinating glimpse into the mind, or the acts anyway, of a true weird genius. Rubin going from LL Cool J to Def Jam to the Geto Boys to Johnny Cash and on and on is a pretty staggering story, and I’m always interested to know what he’s going to do next. Him getting a boat as big as Columbia Records to steer is a big story indeed.

And he says one of the first acts he will sign is this guy he saw on the UK’s version of American Idol, Britain’s Got Talent! (which is a wonderful, self-conscious, defensive title if I ever heard one). The guy’s name is Paul Potts, and Rubin says his appearance on Britian’s Got Talent! makes him cry every time he watches it.

Well, I think, Rubin’s a sensitive soul, isn’t he? But I’m curious, so I bop on over to YouTube and check the guy out.

Oh. My. God.

After recovering my wits, I show this to my wife, to see if I’ve been genuinely moved or have merely been set up for a sucker-punch. She tries to remain calm, says that she doesn’t know anything about opera, has no idea if the guy’s “any good” or not, doesn’t know if she’s reacting to the quality of the guy’s voice or the situation he’s been placed into. But yeah, she’s floored too.

Me, I say it’s only partly his voice and it’s only partly the situation. For me it’s his face. Look at his face before he goes on, and as he stands there before his judges. “Judges” being a loaded word here — he looks like he’s facing his executioners. He looks like a beaten man. He looks like a man who’s had every ounce of hope beaten out of his soul by life, by Britain, by whatever dead-end grind he’s required to endure in order to make ends meet. He looks like he doesn’t even want to be there. Hell, if I had music like that going around in my head, Britain’s Got Talent! is probably the last place I’d want to be. Who with music like that going around in his head would choose to seek the approval of Simon Cowell? And yet here he is.

Then he starts singing, and his face completely changes. First it gains a sense of power, something he controls. My guess (projecting here, obviously) is that he feels very little control over anything in his life, but God Damn It, he knows how to singthis goddamn aria. Then, as the tune builds to its climax, something else comes into his features. It’s not just power, or control, or happiness — it’s defiance. Paul Potts has looked at the dawn of the 21st century and said “You know what? Not everything has to be crappy and ugly and shiny and cheap and brutal. People don’t know that beauty and truth are still possible in this world, and damn it all, I’m going to do something about it.

When he takes the stage he looks like the cell-phone salesman I would cross the store to avoid, but the look on his face as he sings the climax of this aria is one of a general leading his troops into battle. This is madness? THIS! IS! OP-ERA!! Then he finishes and becomes that shy young man again. Incredible.

The fact that he chose a venue like Britain’s Got Talent!, a show dedicated to the idea that art is a competition to be “won” or “lost,” to launch his tiny cultural offensive, makes him a kind of cultural suicide-bomber. Into the temple of the cheap and shiny he has smuggled his brave message of defiance and hope.

iTunes catch of the day: Dean Elliott’s Zounds! What Sounds!

I have no idea how this LP ended up in my family’s record collection in the mid-60s (except that my father worked tangentially with animators in Hollywood for a while), but I discovered it when I was about 7 and it immediately became my favorite record of all time (surpassing “Snoopy vs. the Red Baron” by The Royal Guardsmen. Whole afternoons would pass while I played Zounds! What Sounds! over and over in a state of bliss.

What the record is, basically, is a collection of jazz and swing standards conducted by Dean Elliott, who, as far as I can tell, was to Tom and Jerry cartoons as Carl Stalling was to Bugs Bunny cartoons. The arrangements on Zounds! are jumpy enough all by themselves, but then they are augmented by what can only be termed “wacky cartoon sound effects.” And so a song called “Trees” is driven by the sounds of rhythmic sawing, a song called “It’s a Lonesome Old Town” is festooned with spooky crickets and hooting owls, “The Lonesome Road” is punctuated by the sounds of backfiring cars and tooting horns, and a song called “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was” is inundated with the sounds of a thousand clocks and watches ticking and bonging. Boy, that sounds really stupid and annoying, doesn’t it? And yet it comes off as endlessly inventive, infectiously enthusiastic and wildly ecstatic. Or at least it did to my seven-year-old brain.

Then my family went bankrupt, my mother died, I ran away from home and endured about twenty years of soul-crushing poverty, and forgot all about the innocent joys of Zounds! What Sounds! so much so that before long I thought perhaps I had dreamed it.

Many years later, I was at the Brooklyn Academy of Music watching a show by Pina Bausch, who uses whole dump-trucks of music snippets in her marathon 3-hour dance pieces, and out of nowhere, between the German cabaret numbers and the Ligeti, “The Lonesome Road” by Dean Elliott came blasting out of the sound system. Needless to say, I forgot all about the cerebral, angular, angsty choreography on display and was once again a seven-year-old in the suburbs of Chicago, innocently, joyously leaping about the house like a bug-eyed idiot to the manic strains of Dean Elliott and his Swinging, Big, Big band. The record I had come to think of as long gone had been found! By a skinny, severe, middle-aged German choreographer! By jiminy, I said, if Pina Bausch can find this record all the way over in godless Germany, I can certainly find a copy in New York City!

Which I did. Needless to say, it was long out of print and never a popular item to begin with (I’m guessing), but I was able to track down a bootleg CD copy at the now-long-gone Footlight Records, which specialized in obscure recordings of Broadway showtunes and other music outside the purview of Tower Records. Hearing it again after thirty years, I was instantly transported back to simpler days, when jazz standards hoked up on cartoon sound-effects could supply all the adrenaline I needed.

When I got my iPod, Zounds! What Sounds! was one of the first CDs I transferred, but it’s only 12 tracks in an ocean of over 18,000, so it doesn’t come up much on shuffle (which is what I almost always have iTunes on). Today “I Didn’t Know What Time it Was” came on, sandwiched in between Fiona Apple and John Zorn, both of whom I think would have been comfortable with the comparison.

For those interested, apparently Basta! has done a proper re-mastering of this left-field classic.

The mysteries of iTunes

It is not an exaggeration to say that iTunes changed the way I listen to music, literally overnight. And I do mean literally.

I used to worship at the Altar of the Physical Object. I own about 4000 vinyl records and perhaps 1000 CDs, and they have always gotten the premium wall-space in my house. I used to sit for hours listening to them, holding the jacket or jewel-case the disc came in and perusing it as I listened, on headphones if the rest of the household was sleeping. That’s how I listened to music for about 30 years.

Then, one Christmas a few years ago I got an iPod, plugged it into the computer and started downloading CDs. By morning, I had downloaded all of the Beatles, all of Bob Dylan and all of Elvis Costello onto my iPod, about 2000 songs altogether, and had barely even begun to put a dent in the storage capacity of the thing. And I turned around and looked at those racks and racks of CDs and thought “Why the hell do I own all these things? They take up so much room.”

Well, I still own all those CDs but the fact is, I don’t ever listen to them. I bring a CD home from the store, I load it directly into iTunes and it goes into rotation, along with the other 19,000 other songs, all playing in a random order. I like to think of iTunes as a radio station that only plays things I like to listen to. And at 19,000 songs, it’s amazing to me the things it comes up with I have no memory of ever hearing before.

I rarely listen to one album at a time, if I’m in a specific mood for something I listen to everything by an artist or genre on shuffle. If there are a number of recent purchases I put them all into a “new stuff” playlist and listen to them all on shuffle (currently, my “new stuff” playlist includes new albums by Springsteen, Graham Parker and Sinead O’Connor, plus a McCartney live CD from a few years ago I picked up for free in a “buy three used CDs, get the fourth free” deal). I haven’t sat down and listened to a CD from beginning to end in years and I have a feeling I’m not alone in this.

So I’m pretty impressed with iTunes, I gotta say. I do have one question: the album graphics feature — how does that work? Because the whole thing is a mystery to me.

It seems that when I load a CD into iTunes, iTunes goes to its database and sees if there is artwork available for it. If there is, that artwork gets downloaded onto your computer. But if that is so, why do a great number of my albums not have artwork available?

The Beatles I get — their work is not available through iTunes (yet). But then what about Paul McCartney? He just recently, to great ballyhoo, made all his stuff available through iTunes, but none of his album artwork shows up on my iPod. With one curious exception — London Town, which, for some reason, does not show up as London Town at all, but rather as something called Continuous Wave by a Paul-Weller-looking lad called PMB.

Similarly, I have a Led Zeppelin box set, and iTunes gives some albums artwork and ignores others. The comical thing is that the artwork it grants is not only not for the appropriate album, it’s not even for a Led Zeppelin album — rather, it displays in all cases the cover of Dread Zeppelin’s Un-led-ed — which, I’m sure you will agree, is not the same thing. Even stranger, iTunes illustrates Big Black’s hardcore classic Songs About Fucking with what looks like the cover to an earthy soul album called Still Conscious, an album so obscure I can’t even find a reference to it at Amazon (which is saying something). The Breeders’ Safari EP is illustrated with the cover of the album Safari by someone named Bent Hesselmann. Selections from Beck’s Guero are illustrated by the cover from Beck’s Guerolito, which makes everything very confusing. Songs from Stereolab’s Refried Ectoplasm are illustrated by the cover of Stereolab’s ABC Music. And so on.

Of the 59 Elvis Costello albums in my collection, iTunes provides artwork for The Delivery Man, The Juliet Letters, Mighty Like a Rose, North, Spike and When I Was Cruel, but ignores all the others, even though they’re all for sale through iTunes. Similarly, I have something like 110 John Zorn albums in iTunes, and some of them are pretty darn obscure, but iTunes recognizes some (like Ganyru Island) and is confounded by others (like The Circle Maker), and it doesn’t seem to have anything to do with whether they’re available through iTunes.

In other instances, iTunes will correctly identify a song, but assign it to a different album — it takes the selections I have from a Little Richard greatest hits album and gives them the cover of a different Little Richard’s greatest hits album. Or it will take a hit song from one album and display the cover for a greatest hits album (which I might not even own) because that song also appears on the greatest hits album. Or it will display a different edition from the one I own, like it does for Miles Davis’s ‘Round About Midnight, where it displays the “Legacy” edition instead of the plain-old rotten edition I have.

Brand-new albums, like Lucinda Williams’ West or Springsteen’s Live in Dublin or McCartney’s Memory Almost Full get no illustrations at all, despite being heavily promoted on iTunes, but the White Stripes’ Icky Thump comes sailing through with no problem.

Does anyone out there know how this works and what accounts for these bizarre discrepancies?

A NOTE ON THE ILLUSTRATION: This is a screenshot of my iTunes file, arranged by Play Count. Those with a large-enough monitor can readily see the impact of having two small children in my life — songs from Yellow Submarine and They Might Be Giants’ Here Come the ABCs make up 21 of my top-25 songs, the result of having the iPod in the car with the kids (and Tom Waits’s “Underground” is there as the result of showing up in the soundtrack to Robots). Soon these songs will be overtaken by selections from the Star Wars soundtracks.

McCartney part 8: the insecure, paranoid loser

I can’t find the reference for this, it’s in one of these books I have but I can’t find it, so maybe I have the details wrong, but this is one of the things that drives me completely crazy about McCartney and, after everything else is sorted out, my feelings about his music, the shape of his career, his professionalism, his lack of inspiration, etc, after all that is sorted out, this is the thing that still gets to me.

The story, as I remember it, is that McCartney is in a hotel lounge, and the pianist is playing standards. The pianist takes a break and McCartney goes over to look at the guy’s piano. The pianist has been playing from a standard “fake book,” (maybe this one), and McCartney, amused, flips it open to see what songs are in it. When he comes to “Yesterday,” he is chagrined to find it credited solely to John Lennon.

This ruins his day.

He calls up the publisher of the fake book and learns that, due to space restrictions, they only credit the first songwriter listed on any given song. It’s nothing personal, they do it I guess with Lieber and Stoller, Gershwin and Gershwin, Holland, Dozier and Holland too.

This throws McCartney into a terror. Not being listed as the co-composer of “Yesterday” in this hotel-pianist’s fake book shakes McCartney to his core. It doesn’t matter to him that he’s listed as the co-composer of “Yesterday” every time it appears on a Beatles or McCartney record, or in any of the other of hundreds of incidents when someone has published a recording of it, it doesn’t matter that anyone with a passing interest in popular music knows that “Yesterday” is McCartney’s song, that the Beatles didn’t even play on it, it doesn’t matter that no song could be more obviously a McCartney song than “Yesterday,” it doesn’t matter that McCartney’s gigantic royalties don’t observe what is printed in a hotel-lounge-pianist’s fake book — this thing lists it as a Lennon song and that freaks the ever-loving shit out of McCartney.

Feeling the harsh wind of posterity breathing down his neck, McCartney launches a massive offense to claim his share of the Beatles story. Lennon’s murder in 1980, he feels, has given Lennon an unfair advantage in the “genius” sweepstakes — people, McCartney feels, are under the impression that the Beatles were “John Lennon’s band” and that Paul was somehow just puttering around in the background, playing bass or something. Maybe he feels that people equate him with John Paul Jones or John Entwhistle or — gasp — Bill Wyman.

(There are some legitimate causes for this paranoia — in McCartney’s mind, anyway. John Lennon was inducted into the Rock n Roll Hall of Fame many years before McCartney and McCartney, I’m told, was appalled when Andrew Lloyd Webber got a knighthood before he did.)

How serious is this problem? Here’s how serious. McCartney enlists the help of pal-from-the-old-days Barry Miles to write Many Years From Now, which goes through the Beatles’ career, incident by incident, album by album, song by song, line by line, for 720 pages. If this was a passing problem, I would guess that McCartney might devote an afternoon or two to making some inquiries and then rest assured that his place in music history was secure. But to go on for 720 pages about who thought up the haircuts and who thought up the collarless suits and who’s idea it was to grow mustaches and who thought of putting the orchestral climax into “A Day in the Life” and who came up with the melody for “In My Life” and who introduced who to Yoko Ono and who was out doing research while someone else was lying around his suburban mansion getting high, my God. Don’t get me wrong, I love hearing these stories and what’s more, I trust McCartney’s memory — I think he’s telling the truth. What’s more, I think the book serves a valuable purpose, delineating how these cornerstones of popular culture were designed and built. But when page 1 has McCartney saying “I loved John, I would never try to take anything away from his reputation,” and the ensuing 719 pages proceed to do just that, it gets a little creepy.

(I sense that McCartney is telling the truth about these things not necessarily because he says so, but because the things he says fit with the evidence — Sgt Pepper has the structural underpinnings of many subsequent McCartney albums, “In My Life” sounds like a McCartney melody, not a Lennon melody, so forth. Someday, I’ll do a post on the Shakespeare Authorship question.)

His campaign doesn’t stop there. He calls his new album Flaming Pie, the title of which refers to a John Lennon quote regarding the origin of the name “Beatles” — “I had a vision that a man came unto us on a flaming pie, and he said, ‘You are Beatles with an A.’ And so we were” — except Paul here claims that he, in fact, is the “man on the flaming pie.” Nice.

He releases Paul is Live, a concert recording from one of his 90s tours. The cover of the CD is a (extremely poorly) Photoshopped version of the Abbey Road cover — with all the other Beatles removed and replaced by a sheepdog. Not only is this bad, bad album cover art (oh God, like Abbey Road hasn’t been parodied enough times), it negates the other individuals who worked on Abbey Road (oh, remember that album Abbey Road? Yeah, that was mine, did you know that?) and it also, for those in the know, reminds everyone that the Martha of “Martha My Dear” was McCartney’s sheepdog. Because maybe there are people out there who think that Martha was Lennon’s sheepdog, I guess.

This is all irritating enough (and there is more where this came from), but then it gets ugly. McCartney, I’m told, can’t get past this incident in the hotel lounge. It eats away at him, he can’t stand it. Why, if this goes unchecked, hotel-lounge pianists the world over might introduce “Yesterday” as a John Lennon song until the end of time. He knows it’s a little late to call do-over on a decision he made with his friend forty years ago to make the credits read “Lennon/McCartney,” but the “Yesterday” thing just bugs the shit out of him, so he calls up Yoko Ono and asks, politely, if it would be okay with her if the credit were reversed for just this one song. John didn’t help him with any of the words, nor with any of the melody, and all this is well-documented, and it is Paul alone on the recording, and everyone knows that, and he’s not asking to have John’s name taken off the song, Yoko wouldn’t be losing a penny of royalties, Paul wants only to have the credit reversed, so that, in the future, no inebriated hotel-bar patron might mistakenly hear that “Yesterday” was written by John Lennon.

Yoko politely declines Paul’s request.

Now it’s war — it’s the battle of the cold-blooded, iron-willed bastards. Paul may be a brilliant, canny businessman and an absolute tyrant in the studio or boardroom, but he’s up against Yoko Ono, who never liked him and who is no slouch in the boardroom herself (for all her starry-eyed, peace-n-love posturing). And besides, she holds all the cards. It seems like such a small thing, but when Yoko has the opportunity to irritate Paul, there is apparently no such thing as a slight too small (let’s not forget, the rumor is that it was Yoko that tipped the Japanese police to McCartney carrying pot into Japan in 1980 — on top of everything, she’s a narc!).

McCartney puts out another crappy record and goes on another tour. The next live album, Back in the US (Paul seemingly giving up on selling himself as a solo artist any more, now he’s just “ex-Beatle Paul”) has a number of Beatles songs on it, and McCartney pointedly lists himself first as the composer of every one of them. Just to irritate Yoko, to goad her into trying to sue him or something. In his mind, there will be a public outcry from Yoko and that will push the issue into the public realm and then McCartney can act all innocent and everyone will say how McCartney has been cheated out of his rightful credit on all these wonderful songs that he wrote and John Lennon really didn’t, you know. I’m not making this up, he actually talks about this in the media, that this was his plan. It’s all so petty and bizarre and paranoid that it makes me recoil in disgust.

I know that Paul McCartney is a pillar of 20th-century culture. I know he was a large part of why the Beatles were so great, especially in the latter, greater half of their trajectory. Everyone knows that. My wife knows that, my children know that. Anyone with the ability to both read and listen to music knows that. I think everyone in the world knows it except Paul McCartney.

Anyway, he seems to be better now. I don’t know if it was the knighthood or the second marriage or the death of George Harrison or the billion dollars or so that he has to comfort him, but somewhere in there he gave up his pursuit of Beatle-history-dominance, decided that maybe being Paul McCartney was a good enough gig after all. Personally, I think he’s taking it easy to reduce his stress; he’s bound and determined to outlive Ringo — and then there will be no one to question him.

McCartney part 7: John v Paul

The competition between John and Paul is the engine that drove the Beatles to ever-higher feats of compositional glory. It could even be argued that, from Sgt Pepper onward, the Beatles became Paul’s group, that if it were up to the others there wouldn’t have been any more Beatles albums at all after Revolver. And yet they continued to put out masterpieces on a schedule of months (their record company was very unhappy with them for waiting a punishing 18 months between the albums Sgt Pepper and The White Album, with only Magical Mystery Tour, “All You Need Is Love,” “Lady Madonna,” “Hey Jude” and “Revolution” to sell in between — sweet hopping Jesus, what a schedule). The fact that most bands these days can’t be bothered to put out mediocre product on a schedule of decades says a lot for McCartney’s professionalism and ability to inspire.

The competition between Lennon and McCartney’s continued after the Beatles breakup, but took on a much uglier, detrimental turn. It would be nice if these two songwriting titans could bring themselves to compete with the other acts of the day, but the fact was that there were few others who could match their talents. Who is Lennon going to compete with, Bernie Taupin? Is McCartney going to worry about Steve Miller breathing down his neck?

So while it is unhelpful to compare apples and oranges (you know, why didn’t McCartney start an Orange label for his records? That would be just like him), a Beatle fan in the 70s could not help but compare the products of their heroes, and Lennon and McCartney knew it. For the purposes of this piece, I’m going to begin the competition in 1970, even though Lennon started putting out albums before that; the competition ends in 1980 for obvious reasons.

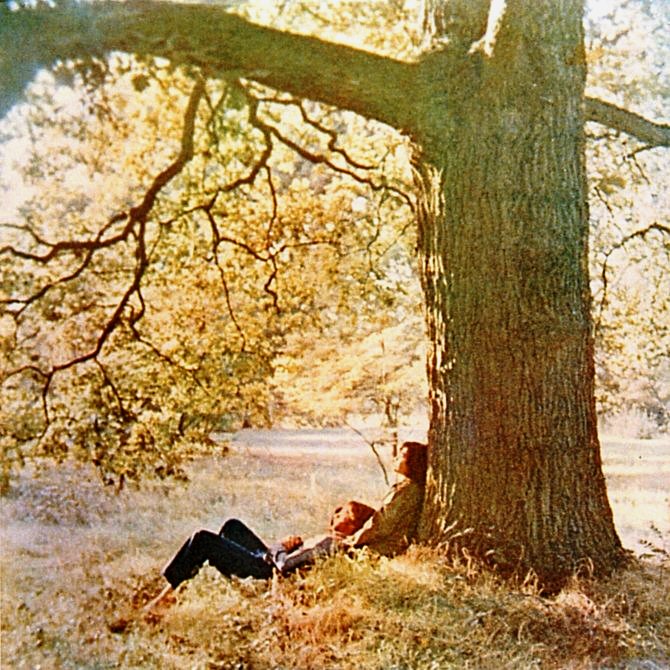

1970: Plastic Ono Band v. McCartney

Directly after the Beatles breakup, both John and Paul decided to remove themselves from the everything-but-the-kitchen-sink, Technicolor polish of the late Beatles style, opting instead for stripped-down, raw, home-made sounds. John recorded Plastic Ono Band, a devastating blast of pain and personal anguish. This was not good-time music, it was punishing, harsh and uncompromising. McCartney, on the other hand, didn’t sound uncompromising, it sounded unfinished, like a collection of demos and out-takes, spare, slender and unassuming. Fans might not have bought Plastic Ono Band, but they could at least respect it for what it was. But they hated McCartney, found it disappointing and limp, a poor offering from the man who engineered Abbey Road. No wonder that neither album was hit, but George’s bloated, over-produced All Things Must Pass was — it sounded like genuine Beatle product.

Plastic Ono Band was a huge influence on me; I’d never heard anything like it before (in 1977, when I bought it). It was more punk than punk and more raw than an open wound. McCartney, on the other hand, seemed irrelevant at best, lazy and unfocused. Nowadays however, I never listen to Plastic Ono Band and McCartney is a consistent delight on my iPod. When I do hear songs from Plastic Ono Band, I keep thinking “Okay, John, okay, I get it,” while the slight, unfinished-sounding songs of McCartney continue to beguile and intrigue.

1971: Imagine v. Ram

In “How Do You Sleep?” Lennon snarls “The only thing you done was ‘Yesterday,’ and since you’re gone your just ‘Another Day.'” These days all I can think of that is “Well, ‘Another Day’ is a fine Paul 1 song, and ‘How Do You Sleep’ is a vicious, unfair slab of character assassination.” Imagine was Lennon coming to his commercial senses, a much friendlier, more polished piece of Beatle product than the “I dare you to like me” Plastic Ono Band, while Ram seemed to be even more irrelevant than McCartney. The anger of Plastic Ono Band was directed outward instead of inward and tempered with a more radio-savvy approach to production. I loved both of these records when I heard them (again, at least six years after they came out), but these days I tire of Lennon’s sloganeering easily and Ram seems better and better as the days go by.

1972: Some Time in New York City v. Wild Life

In 1977 I was obsessed with John Lennon and defended Some Time in New York City to anyone who would listen. Not that there were many 16-year-olds in my acquaintance who had any awareness of Some Time in New York City — I had to special-order it from my local record store, who had never heard of it but professed to liking the packaging when I came to pick up my copy (that same store, which also sold greeting cards, had a policy of ordering two of anything that was special-ordered, reasoning that if one person is interested, another might be, and I took it as a point of pride that I could walk into that store for years afterward and see their second copy of Some Time in New York City still sitting in their bin). Lennon was a hero to me, a man who was using his fame for purposes of good, making daring musical choices standing as a man of the people, defender of justice and champion of peace. Some Time in New York City, of course, then as now, is a terrible, terrible album, an aural nightmare of blare and cacophony, accent on phony, ugly and shrill, hectoring, bombastic, dishonest and nauseating.

It wouldn’t be hard to top Some Time, McCartney could have put out nothing but silence (which is really the only appropriate response) and still come out ahead. Wild Life, however, presents an even more extreme case of redemption. It was an outright commercial disaster when it came out; I put off listening to it for years and hated it when I finally did. I bought it only when I was able to find a copy for less than three dollars, just to complete my collection, and only listened to it once, slack-jawed in horror at its laziness, fuzziness and lack of direction. Then, just the other day I put it on again and couldn’t get over how good it sounded. All those old adjectives still applied, but now they seemed like positive attributes. Wild Life is lazy, fuzzy and lacking in direction, but compared to what became the typical McCartney product of polish, sheen and calculation it positively glistens with life and tunefulness. “Bip Bop,” a song I used to cite as the nadir of McCartney’s composing career, is now charming and delightful, “Dear Friend” is poignant, honest and revealing, and “Tomorrow” is one of his overlooked gems on a level with “Every Night” and “That Would Be Something.”

1973: Mind Games v. Red Rose Speedway

It’s hard to imagine, now, two giant superstars putting out competing albums every year. These days they could not possibly be expected to keep up the pace and not have the material suffer. And while Mind Games is a marked improvement over Some Time in New York City (recordings of weasels being tossed into a wood-chipper would be a marked improvement over Some Time in New York City), Mind Games strikes me as weak and perfunctory. Back in the day I could work up some enthusiasm for it, but even then it seemed like a pale imitation of Imagine. There isn’t anything on it as impressive as “Gimme Some Truth” or “I Don’t Wanna Be a Soldier” or “How Do You Sleep?” and Lennon’s save-the-world-ism even back then sounded naive, silly and ineffective.

On the other hand, back then I found Red Rose Speedway to be a baffling dead-end of misfires and time-wasters. Time, and lowering of expectations, has leavened my opinion of it, but it still strikes me as underwhelming and unfocused (and now I find out that it was supposed to be a double album! sheeesh!). I’m giving Mind Games the edge here.

1974: Walls and Bridges v. Band on the Run

Okay, Band on the Run came out in 1973. Sue me. (Jesus, McCartney put out two albums in 1973, and “Live and Let Die” — what the fuck is wrong with U2, R.E.M., Bruce Springsteen? Who are these poseurs?)

Back in the day, I counted Walls and Bridges “Plastic Ono Band in color,” Lennon’s masterful summation of all his obsessions, produced with care and skill, full of wit and imagination. I still like it okay, but time has not been kind to it. It now feels padded, self-conscious and, again, dishonest. I regularly skip over “Whatever Gets You Thru the Night” and have little patience for “Bless You,” “Scared,” “Old Dirt Road” and “Beef Jerky.” The big production number, “Nobody Loves You When You’re Down and Out,” strikes me as uncomfortably self-pitying and morose, everything Plastic Ono Band was not.

Beatle fans reveled in Band on the Run at the time; Paul’s career suddenly snapped into focus — it seemed like this was finally his Plastic Ono Band. I talked myself into liking Band on the Run at the time; it certainly provided more Beatlesque polish and entertainment value than anything else McCartney had put out up to that point, but it now strikes me as overhyped, overproduced and even ponderous in places. I love the title tune, “Jet,” and “Helen Wheels,” but otherwise the album seems cold, impersonal and hollow, listenable as it is.

1975: Rock n Roll v. Venus and Mars

I loved Rock n Roll back in the day, I found it bracing, fun, invigorating and vital. Venus and Mars I found cutesy, vague, self-important and annoying. What’s changed since then is I’ve heard the originals that Lennon was singing on Rock n Roll and find his production choices to be dreadfully, tragically wrong-headed. I bought the remastered CD when it came out a few years ago and couldn’t finish listening to it — it was loud, sluggish, hugely over-produced and leaden, everything the original versions of those songs were not. Ironically, or perhaps not, McCartney went on to record superior versions of many of the songs from Rock n Roll — whether this is mere coincidence or yet another backhanded attempt on McCartney’s part to degrade Lennon’s reputation is unknown to me.

My opinion of Venus and Mars remains unchanged.

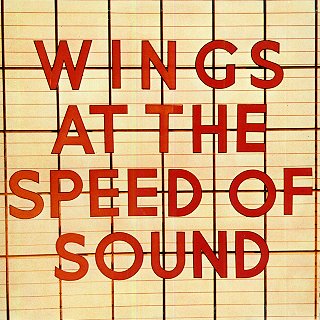

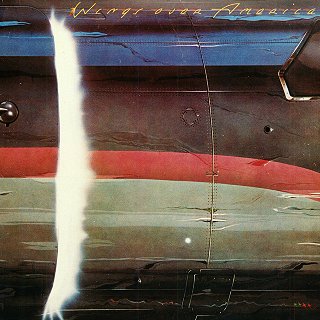

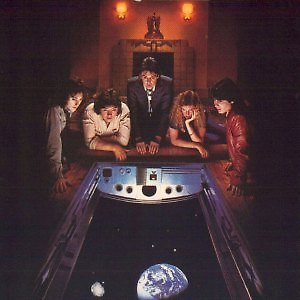

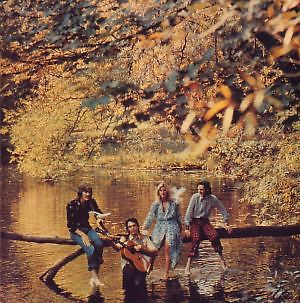

1975-1979: Lennon abstains

Lennon, as is well known, declined to record for the next five years. That would seem like a natural state of being for an artist of Lennon’s stature today, but back then it was an eternity. McCartney ran the field free of competition for those five years, releasing At the Speed of Sound, Wings Over America, London Town and Back to the Egg, all of which were more-or-less commercial smashes, in some cases mysteriously. At the Speed of Sound is godawful — whatever possessed McCartney to actually share album space with the other members of Wings? What the hell was he thinking? Did he really think this band could compete with the Beatles? How is that possible? Or did he just not have enough songs to fill an album and had to get something into the stores to promote on a world tour? In any case, this is the one Wings album I have yet to be able to listen to all the way through. Wings Over America, on the other hand, presents a compelling case for Wings as a musical statement separate from, if not quite equal to, the Beatles. London Town, an album I virulently despised when it came out, has aged surprisingly well — whenever a McCartney tune comes up on iTunes and I think “hey, this isn’t bad, what’s this?” it invariably comes from London Town. Which is not to say that London Town doesn’t contain its share of filler and dreck — “Girlfriend” leaps immediately to mind, as well as non-songs like “Cuff Link.” Back to the Egg, on the other hand, I loved immediately and is still my favorite Wings album by far. It was reviled and unpopular when it came out, which never made sense to me. I loved the weird avant-gardisms, I thought “Getting Closer” and “Spin it On” crushed, and found all the little linked songs spooky and intriguing. My opinion hasn’t changed — every time a Back to the Egg song pops up on iTunes I still feel a charge.

1980: Double Fantasy v. McCartney II

It is, of course, difficult to separate Double Fantasy from the context it appeared in — coming out days before Lennon’s murder, it took on tragic dimensions of shattered dreams and starcrossed love. I, for one, was greatly looking forward to hearing it and bought it on its release date — and was distinctly let down. Lennon’s songs felt weak, thin and slight, and Yoko’s, well, I’m going to go out on a limb here and say that, in my opinion, Yoko’s songwriting talent is not the equal of John’s. There, I said it. I could kind of work up some enthusiasm for the goofy charm of something like “I’m Your Angel” but otherwise itwas an uphill climb. Of course his murder changed all of that.

Time has not been kind to Double Fantasy. Lennon’s songs stand up well for the most part, but no agency on Earth can compel me to listen to any more Yoko Ono. And this coming from someone who enjoys “Cambridge 1969” from Life With the Lions and side 2 of Live Peace in Toronto. Still, seven decent songs on a record is still pretty good, even if some are too sappy and others are too skinny, and I would have very much enjoyed to see where Lennon was going to go from there.

McCartney II has all the sketchiness and home-made-iness of McCartney and absolutely none of its charm or delight. It is a tinny, clangorous horror, even if TLC swiped the opening lines of “Waterfalls.” “Secret Friend” goes on for a stultifying 10 and a half minutes!

Both were big hits.

McCartney part 6: know your Pauls

Paul 2, Pop surrealist: this Paul was the natural development of Paul 1. Having risen to the top level of his profession, able to have a hit without even trying, this Paul began turning song forms on their heads and stretching the limits of popular songwriting. Forms are splintered, juxtaposed, overlaid and examined. Less attention is paid to universality and more is paid to creative development. Personal statements occasionally emerge but never dominate. Words are chosen for the way they scan instead of what they might actually mean. When this strategy works, the results are magical and captivating. “Hey Jude” is probably the epitome of this Paul. “Penny Lane,” “Lady Madonna,” “Rocky Raccoon,” “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” are all sterling, indelible works of Paul 2. “Big Barn Bed,” “Let Me Roll It,” “Spin it On” are lesser but still worthy versions of this Paul — Paul 2 on autopilot. The key to this Paul is his ability to create songs that sound like they’re about something but which defy easy categorization. This Paul has the unmatchable skills of Paul 1, but is employing them to more personal ends.

A subset of Paul 2 is Paul 2A, the pop collagist, composer of “Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey,” “Band on the Run,” “Live and LetDie.” This Paul takes the lyrical strategies of Paul 2 and applies them musically as well, taking small ideas and making them appear to be bigger through dramatic juxtaposition. This is one of the most distinct Pauls, a Paul not easily imitated, although John did an excellent job of it with “Happiness is a Warm Gun.”

Paul 3, peddler of Twee British Nonsense. A kind of WS Gilbert on drugs, this Paul has roots deeper than Tin Pan Alley, stretching back to Lewis Carroll and further. This Paul has cut all ties with narrative and conventional pop-lyric forms and constructs songs from pure sounds, not paying a whit of attention to meaning but a great deal of attention to context and especially arrangement. “Helter Skelter,” “Bip Bop,” “Morse Moose and the Grey Goose,” “Temporary Secretary” are examples of this Paul.

Paul 4, restless creator of abstract soundscapes. This Paul likes sounds for their own sake and employs them in evocative and intriguing ways. This Paul would get along well with Brian Eno, although I don’t think anyone’s ever introduced them. “Flying” is probably the earliest emergence of this Paul. McCartney and McCartney II are filled with compositions by this Paul, as are the albums by The Fireman and Liverpool Sound Collage. This Paul is often overlooked, due to the other Pauls habit of hogging the spotlight. I think this Paul would be happy to work more, but Paul 2 keeps demanding more time.

Paul 5, ambitious composer of classical stuff. I honestly don’t know much about this Paul.

Paul 6, composer of embarrassing, witless, leaden, flat-footed anthems. “Ebony and Ivory” is the apex of this Paul’s career. “Give Ireland Back to the Irish,” “Freedom,” “Pipes of Peace,” “Looking for Changes” are others. I don’t know what the hell this Paul thinks he’s doing but I wish he’d stop.

This categorization of Pauls is meant only as a rough guide. Many songs feature contributions from more than one Paul. It began as I was trying to locate a “position” for McCartney, a place where his art begins, trying to identify the “real” Paul. I felt I needed to find this point so as to discern what is McCartney’s “self-expression” and what is him throwing any old word into a song because he likes the way it sounds, or whether his habit of throwing any old word into a song is his expression of self.

Don’t forget, for a long time “Yesterday” began “Scrambled eggs, oh baby how I love your legs.” This would have been a classic Paul 2 line, but Paul1 prevailed. Similarly, in “Hey Jude” the song was intended (he says) as a message to Julian Lennon, and began “Hey Jules.” Paul 1 instinctively felt that “Jude” scanned better than “Jules” so the personal message went out the window. But Paul 2 (in the form of John Lennon) insisted on keeping the nonsense line “the movement you need is on your shoulder” over Paul 1’s protest, which took the song to a new level of poetry. “Let Me Roll It,” I’m told, is a response to Lennon’s blistering “How Do You Sleep?” but what kind of response is this? It’s cold, remote, glancing and glossy, the opposite of Lennon’s scathing vitriol.

Lennon’s confessional, purging style of songwriting is anathema to all the Pauls. Rarely does he expose much of himself in any meaningful way (although it does occasionally happen, as in Wild Life‘s “Dear Friend;” I’m also willing to concede that his many love songs to Linda, “Long Haired Lady” being the most obvious, are personal, honest and direct). Strangely, I think one of McCartney’s most focused, honest and accomplished statements is “Silly Love Songs.” I think that’s his “Imagine,” his statement of purpose, the spot he’s placed his flag. The lyric isn’t surreal or meaningless, it’s direct and accessible. He’s coming out and saying exactly what he means, rather in the manner of his awful, flat-footed anthems; no metaphor or imagery is employed. The fact that the song is incredibly annoying is beside the point — this is his 1970s, height-of-his-fame Major Statement.

Give My Regards to Broad Street

Morbid curiosity brought me to watch this movie — slack-jawed astonishment kept me watching.

It’s awful, a train wreck, but not in the way I thought it would be.

It’s utterly wrong-headed, flat-footed and depressing — but again, not in the way I thought it would be.

Paul McCartney (Paul McCartney) is a successful musician and composer with a busy schedule. He’s got a business meeting, a recording session, a complicated film shoot, a band rehearsal and a radio interview, all in one day (given McCartney’s passion for appropriating all of Beatles history, I’m surprised the movie’s not titled A Day in the Life). At his morning business meeting, it is revealed that the master tapes for McCartney’s new album have gone missing. I’ll spare you the details, but the upshot is that if McCartney does not recover the missing tapes by midnight, the record company will be taken over by a big evil corporation. Why this should be so is not explained. Why the poorly-run business affairs of the record company should be McCartney’s concern is also not explained.

So: McCartney has to find his missing tapes before midnight and he’s got an ultra-busy day already planned. What’s he going to do to recover the tapes? If you guessed “nothing,” you’re right! In fact, no one in the cast ever does anything to actually try to recover the missing tapes! The label executives sigh and keen, various roadies and lackeys posit theories and sling accusations, but not one character actually commits a single action toward actually righting the imbalance created by the inciting incident. No one makes a phone call, goes ’round to anyone’s house, checks to see if the courier ever got home the night before. Instead, they just show up every now and then and look balefully at McCartney and worry aloud that the big evil corporation is going to take over the record company. And we, apparently, don’t want that, although it seems to me that any record company who’s going to lose my master tapes and does nothing to try to recover them while I bust my ass running all over town trying to create product for them to sell maybe shouldn’t be my record company any more.

So the tapes are missing and McCartney’s feeling the strain. Feeling the Strain would be a more apt title for this movie. McCartney pads through his day, looking doleful, depressed and tired. In a movie about Paul McCartney, written by Paul McCartney, it’s a big fucking drag to be Paul McCartney — all these goddamn recording sessions and movie shoots and band rehearsals and radio interviews, it’s all just a big tiresome pain in the arse. It’s like a remake of A Hard Day’s Night with the youthful joy sucked out, replaced by a heavy cloud of grownup responsibility. In other words, comedy gold!

So — the tapes are missing and Paul has to get them back by midnight, and no one is helping. You would think that would create some kind of crisis for Paul, or at least some kind of impetus to act. But he does not — he’s got responsibilities! He’s got to, why, he’s got to go to the recording studio, where he’s scheduled to record a medley of “Yesterday,” “Here, There and Everywhere” and 1982’s “Wanderlust!” Who is demanding this medley of two classic Beatle love songs and a middling number from Tug of War? I have no idea, but its recording takes precedence over recovering the precious master tapes, which have been given a stated value of 5 million pounds.

Anyway, the recording session takes a couple of hours, as recording sessions do, and then it’s off to the film studio, where Paul is, apparently, filming a musical, or a couple of videos, or something, it’s not clear. One film shoot seems to revolve around another Tug of War song, “Ballroom Dancing,” staged here as a slightly surreal, British take on West Side Story. Why he should be shooting this is not explained, but it at least makes more sense than the next number, a robotic, 80s version of “Silly Love Songs,” with Paul and the band made up like David Bowie, posing like mannequins while a skinny black dancer does The Robot in the foreground. And you thought you didn’t want to see this movie!

How soulless, uncaring and tired is McCartney? He shows up at the movie studio, goes onto the set for his video, starts shooting, and about a minute into the song we realize that Linda McCartney is on the bandstand, playing keyboard, and he doesn’t even acknowledge her. He doesn’t greet her, kiss her, look her in the eye, smile, or nod in her direction. Nothing would indicate that they’re married. Paul On Business is, apparently, a very cold bastard indeed. And just as you’re thinking “Well, it’s a movie, maybe this is supposed to be some kind of alternate-universe McCartney where Linda isn’t really his wife, but then they show him eating lunch in the commissary, and there she is sitting next to him — and he still doesn’t say a single word to her, although Ringo is, for some reason, given multiple scenes where he chats up Barbara Bach (who, strangely, does not play herself, but instead plays a journalist writing an article about Ringo). 42 minutes into the movie, Tracey Ullman shows up. She’s the girlfriend of the guy who disappeared with the tapes. She doesn’t know where he is and she’s upset. McCartney takes a good deal of time consoling her and talking through her problems while his wife Linda sits six inches away, ignored and without dialogue.

Does Tracey provide a clue as to where the missing tapes are? No, she sure doesn’t! Does McCartney press the point? No, he sure doesn’t! So after he finishes shooting his two videos (it’s about 2pm by now) he slouches off to a joyless, perfunctory band rehearsal in a warehouse across town, even though the band he’s rehearsing with is the exact same band he was just filming with at the movie studio. How they managed this is a mystery. We see McCartney leave the movie studio, get in a beat-up van, be driven across town, be dropped off on an empty loading dock, and go upstairs to a rehearsal hall where all the musicians he just left at the movie studio are already set up and ready to rehearse.

Ah but this is all made worthwhile by the songs right? No. It is not. They suck.

Paul is finding it hard to concentrate on work (I can’t imagine why) and finds his mind wandering. His mind wanders a lot in this movie — he remembers the day when he first hired Harry (that’s the guy who’s gone missing with the tapes), he fantasizes about what his pals the record executives are doing now, he worries about what this corporate takeover might mean to his career. Like I say, it’s a big fucking drag to be Paul McCartney in this movie.

Paul asks a roadie if he’s seen Harry. The answer is no. Sigh. Off to a radio interview.

(I realize I was wrong about Paul not doing anything to recover the missing tapes. He does do something — he worries. I’d like to write a Bond movie that adopts this narrative strategy — Bond is told that Blofeld has a big space-laser pointed at London and it’s going to go off at midnight, but Bond’s got a big day planned of clothes-shopping, bar-hopping, card-playing and casual sex, so he can’t really get to the space-laser thing. So instead we see him shopping for clothes, drinking, playing Baccarat, maybe fiddling with some gadgets at Q Branch, all the while worrying about that space-laser and how it’s going to destroy London in a few hours. And everyone keeps coming around and saying “Boy,it’s a drag how Blofeld’s space-laser is going to blow up London in a few hours,” and Bond’s mind wanders to a day a few years ago when he was having lunch with Blofeld and Blofeld said something about maybe building a giant space-laser — or was he just kidding that day?)

Now it’s evening and we’re well into the third act and Paul has still not reacted to the inciting incident. Instead, as he sings “Eleanor Rigby” in a studio for an audience of stupid, uncaring radio personnel (no one in this movie is the slightest bit impressed with the idea of working with Paul McCartney), he has a very long, bizarre, over-produced Victorian fantasy that dares to invoke both “Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe” and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. This fantasy ends with a vision of his wife and friends dying in a tragic boating accident — all because of those lousy missing tapes.

This baroque, incoherent vision apparently rouses Paul to some kind of action, and he drives out to some kind of pub or hotel or something, where he runs into Ralph Richardson, who lives in a dumpy, overstuffed apartment with a monkey. Aha, you think, here’s the big scene where the truth is revealed — it’s Ralph Richardson with a monkey!

Nope. Nothing. Ralph lectures Paul on spending too much of his time running around, because, you know, you never see the world that way. This from a man who does not seem to have left his room, or his monkey, in years.

Now midnight is approaching and the tapes are no nearer to being gotten. Then, a revelation! Paul remembers singing “Give My Regards to Broad Street” to Harry as he went off with the tapes! Aha! To the Broad Street railways station!

Where he wanders around for about ten minutes. No seriously. He’s not looking for anything, he has no clue or hunch, he just wanders around. As midnight approaches, he sits down on a bench and imagines life as a busker, singing Beatles tunes on a railway platform.

Is this the movie’s message? Is this McCartney’s fear, that if a big evil corporation takes over his record company he will become a homeless busker singing Beatles songs on a railway platform?

Anyway, turns out Harry left the tapes on a bench while he went into a storeroom he thought was a bathroom. Case closed.

So Paul calls his wife (the first time he’s spoken to her in the movie) and she calls the record company, who seem relieved, but not that relieved, and everybody’s happy, and the big evil corporate guys are chagrined. And the viewer goes “Whaaa — ?”

Then it turns out the whole thing was a dream. No really. Turns out there are no missing tapes, no corporate threat, no days crammed full of the joyless drudgery of creating pop hits, nothing. The whole thing was a dream Paul had while passed out in the back of his limo on the way to his office. No really.

I note that this was the first and last feature by director Peter Webb.

McCartney, part 4, where it starts getting ugly

Last time, I attempted to pin down what makes the Beatles’ recordings work, or at least what makes them so appealing and deathless to me. I came up with a handful of terms which I would now like to apply to McCartney’s post-Beatle work. These terms are: urgency, immediacy, drama, complexity, joyfulness and experimentalism, coupled to a faultless melodic sense and set to unique, indelible arrangements. How does McCartney’s post-Beatles work compare?

And let me begin by saying this is all terribly unfair. It is axiomatic that all the Beatles did their best work within their group, that the Beatles were a miracle-making music machine substantially greater than the sum of its parts, that there was a chemistry within that band that seems something close to magic. Even McCartney himself seems stunned these days to realize that he was part of this unique musical and cultural force, almost as if it happened to someone else.

And yet, the Beatles standard is both the thing that keeps attracting me to McCartney’s work and appalling me with the results. It’s the single most vital aspect of his development and a kind of sword of Damocles hanging over his head. Every time I put on a McCartney record, I think “this is the guy who wrote ‘Hey Jude,'” and, well, there is nothing that can live up to that standard. No wonder I hated him so hard for so many years.

No, but I mean really hated him. Partly because he was not the Beatles, partly because he was not John and partly because he had betrayed his talent with such abandon and scorn. I hated the album London Town withsuch an intensity that I literally burned the faces off the cover and displayed it in my college dorm that way (keep in mind it was 1978 — I was listening to This Year’s Model and More Songs About Buildings and Food; the pleasant, noodling melodies of London Town weren’t just irrelevant, they were abominations). I was a strong proponent of John at that point, proudly defended Some Time in New York City (who’s an abomination now, punk?) and saw McCartney as not just a sellout but as a pariah, a calculating monster, bringing his immense commercial weight to cloying, irritating ditties like “Coming Up” and “Say Say Say.”

Anyway, so I have this obsession with the guy, and a fascination. I find it impossible to reconcile the pop genius who wrote staggering masterworks like “You Won’t See Me” and “Hello Goodbye” and “Back in the USSR” with the man responsible for “Ebony and Ivory.” So I am compelled to keep probing, investigating further, questioning assumptions, trying to discover what exactly happened to his talent, are things as bad as they seem, has time been kind to his work, is it he who was right all this time and I who was wrong? Does his solo work match the mathematical equation of my last entry? And that sort of thing.

At some point I’ll probably have to sort out what I think of all these albums on an individual basis, but for now here’s a broad overview, taking the terms of McCartney’s Beatles work and applying them to his solo work.

JOY: The first thing one hears when one is introduced to the Beatles and their most arresting quality, Joy is only sporadically present in McCartney’s solo work, although there is often Joy’s little sister Delight, her cousin Charm and their great grand-uncle Pleasure. The calculation and professionalism that bugged me so much as a younger man doesn’t bother me so much any more. Records that seemed cold, passionless and remote now seem to be the work of a man for whom music is a gift, something that comes effortlessly to him. (Effortlessness, however, is a serious problem in a great deal of McCartney’s work, but more on that later.)

URGENCY and IMMEDIACY: Almost nonexistent in McCartney’s post-Beatles work. This seemed like a capital crime when I was a teenager, but of course it’s just part of artistic development. Who could keep up the intensity of the Beatles experience, twelve albums of faultless masterpieces in eight years? Who would demand it? And yet, the man is a supremely talented composer, arranger and melodist and too often he brings his massive talents to bear on sentimental trifles, goofy doodles and flat-footed profundities. I wrote earlier that the Beatles sounded like they had never been in a recording studio before and didn’t know if they ever would be again, but the McCartney of, say, Red Rose Speedway sounds like he lives in a recording studio and has all the time in the world. I can find nothing in the McCartney catalogue that quickens the pulse like “All My Loving” or “Drive My Car” or even “Birthday,” and much that makes my blood run cold, like “Wonderful Christmastime” or At the Speed of Sound.

(If you seek any of the above qualities in McCartney’s solo work, I direct you to Choba B CCCP, Unplugged and Run Devil Run, three albums of mostly covers that are filled to brimming with joy, urgency and immediacy. The last, especially, I recommend highly — its vital, searing presentation of rock-n-roll standards is positively crushing, and finally makes a legitimate bid to connect the McCartney of today with the young man who sang “Long Tall Sally” all those years ago.)

DRAMA: In much greater abundance than joy, urgency and immediacy, although still lacking. I see great dramatic sense brought to songs like “Another Day,” “Live and Let Die” and “Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey,” albums like Band on the Run and Back to the Egg. In each of these, it is the same dramatic sense brought to Sgt Pepper, The White Album and Abbey Road — that is, the drama is brought about through juxtaposition and arrangement, not through the quality of the original material. But these are dramatic peaks — too much of McCartney’s solo work is dramatically inert albums like Pipes of Peace and Press to Play.

COMPLEXITY and EXPERIMENTALISM: These qualities have not abandoned McCartney, nor he them, and he rarely gets credit for them, so I’m going to give some so here. McCartney has the reputation for calculation and commercialism, and yet as I look over his long post-Beatle career I find a restless, creative spirit, consistently burrowing into his talent, challenging himself in interesting and questioning ways, unhappy with straitjackets and only occasionally overtly trying for a big commercial hit. If people want to buy an inoffensive, undemanding bit of silliness like “Coming Up,” is that McCartney’s fault? I see no calculation in it, I see no effort in it at all — it sounds like something he knocked off in a day. But then, the same could be said for the album Please Please Me.

It is, in fact, McCartney’s silliness that often confuses the issue; his sense of British nonsense is both one of his greatest strengths and one of his most damning flaws. When he’s on, nonsense like “Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey” or “Band On the Run” or “Jet” takes on a grandeur and depth that is startling and magical. Even un-grand, low-key albums like McCartney, Ram, Wild Life and Red Rose Speedway positively burst with charm and playfulness (but lack drama or any sense of importance — positive, refreshing attributes in the case of the first two). When he’s not on, the playfulness feels forced and fake — “Morse Moose and the Grey Goose” comes to mind.

With Lennon’s work, experimentalism often took the forefront — records were often experimental at the expense of coherence, professionalism or effectiveness. A Beatle could claim the right to release an album like Two Virgins, but no one could listen to it all the way through. With McCartney, experimentalism often takes the form of half-finished ideas and excessive noodling. As the years pass, I welcome McCartney’s noodling and recoil in horror from Lennon’s indulgent, punishing excesses. But let’s not make this about John versus Paul — that’s a post for another day.

(I’m told McCartney has several albums of ambient music and sound collages released under pseudonyms. I’m curious, but not that curious.)

AND THE REST? McCartney’s melodic sense has never left him, ever. There are oceans of melody on all his records, from the shiny, metallic80s crap of Press to Play to the unassuming, home-made charm of McCartney. What’s different is the sense of importance that permeates even lesser Beatles albums like Magical Mystery Tour or Beatles for Sale. Also omnipresent is his talents for arrangement. No two McCartney songs, even the unmemorable dreck, sound alike. He still pursues sonic landscapes and insists on bringing distinct personalities to each of his recordings. Whether all of them were worth the effort is another question.

DOES HE BEAT THE SPREAD? I’m going to say, hesitantly, yes. Given that the lack of intensity to his post-Beatles work is a natural development and not necessarily a crime, there is still enough in a good deal of McCartney work that is worth listening to. And the equation I came up with (McCartney equals one-third of the Beatles, therefore his solo work can reasonably be expected to be one-third as good) I think holds true. Easily one-third of McCartney’s solo work is very good indeed, even if there’s nothing that can compare to Revolver or Rubber Soul.

However, it’s also true that McCartney’s contemporaries and peers, specifically Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones, are doing work right now that does actually compare favorably to their high-water marks. Is it wrong to expect the same of McCartney? His new album is perfectly listenable, catchy as ever, full of something like joy and devoid of sap. It snaps and swings and even occasionally thunders. That said, there is nothing there that can compare to “From Me To You.”