McCartney part 7: John v Paul

The competition between John and Paul is the engine that drove the Beatles to ever-higher feats of compositional glory. It could even be argued that, from Sgt Pepper onward, the Beatles became Paul’s group, that if it were up to the others there wouldn’t have been any more Beatles albums at all after Revolver. And yet they continued to put out masterpieces on a schedule of months (their record company was very unhappy with them for waiting a punishing 18 months between the albums Sgt Pepper and The White Album, with only Magical Mystery Tour, “All You Need Is Love,” “Lady Madonna,” “Hey Jude” and “Revolution” to sell in between — sweet hopping Jesus, what a schedule). The fact that most bands these days can’t be bothered to put out mediocre product on a schedule of decades says a lot for McCartney’s professionalism and ability to inspire.

The competition between Lennon and McCartney’s continued after the Beatles breakup, but took on a much uglier, detrimental turn. It would be nice if these two songwriting titans could bring themselves to compete with the other acts of the day, but the fact was that there were few others who could match their talents. Who is Lennon going to compete with, Bernie Taupin? Is McCartney going to worry about Steve Miller breathing down his neck?

So while it is unhelpful to compare apples and oranges (you know, why didn’t McCartney start an Orange label for his records? That would be just like him), a Beatle fan in the 70s could not help but compare the products of their heroes, and Lennon and McCartney knew it. For the purposes of this piece, I’m going to begin the competition in 1970, even though Lennon started putting out albums before that; the competition ends in 1980 for obvious reasons.

1970: Plastic Ono Band v. McCartney

Directly after the Beatles breakup, both John and Paul decided to remove themselves from the everything-but-the-kitchen-sink, Technicolor polish of the late Beatles style, opting instead for stripped-down, raw, home-made sounds. John recorded Plastic Ono Band, a devastating blast of pain and personal anguish. This was not good-time music, it was punishing, harsh and uncompromising. McCartney, on the other hand, didn’t sound uncompromising, it sounded unfinished, like a collection of demos and out-takes, spare, slender and unassuming. Fans might not have bought Plastic Ono Band, but they could at least respect it for what it was. But they hated McCartney, found it disappointing and limp, a poor offering from the man who engineered Abbey Road. No wonder that neither album was hit, but George’s bloated, over-produced All Things Must Pass was — it sounded like genuine Beatle product.

Plastic Ono Band was a huge influence on me; I’d never heard anything like it before (in 1977, when I bought it). It was more punk than punk and more raw than an open wound. McCartney, on the other hand, seemed irrelevant at best, lazy and unfocused. Nowadays however, I never listen to Plastic Ono Band and McCartney is a consistent delight on my iPod. When I do hear songs from Plastic Ono Band, I keep thinking “Okay, John, okay, I get it,” while the slight, unfinished-sounding songs of McCartney continue to beguile and intrigue.

1971: Imagine v. Ram

In “How Do You Sleep?” Lennon snarls “The only thing you done was ‘Yesterday,’ and since you’re gone your just ‘Another Day.'” These days all I can think of that is “Well, ‘Another Day’ is a fine Paul 1 song, and ‘How Do You Sleep’ is a vicious, unfair slab of character assassination.” Imagine was Lennon coming to his commercial senses, a much friendlier, more polished piece of Beatle product than the “I dare you to like me” Plastic Ono Band, while Ram seemed to be even more irrelevant than McCartney. The anger of Plastic Ono Band was directed outward instead of inward and tempered with a more radio-savvy approach to production. I loved both of these records when I heard them (again, at least six years after they came out), but these days I tire of Lennon’s sloganeering easily and Ram seems better and better as the days go by.

1972: Some Time in New York City v. Wild Life

In 1977 I was obsessed with John Lennon and defended Some Time in New York City to anyone who would listen. Not that there were many 16-year-olds in my acquaintance who had any awareness of Some Time in New York City — I had to special-order it from my local record store, who had never heard of it but professed to liking the packaging when I came to pick up my copy (that same store, which also sold greeting cards, had a policy of ordering two of anything that was special-ordered, reasoning that if one person is interested, another might be, and I took it as a point of pride that I could walk into that store for years afterward and see their second copy of Some Time in New York City still sitting in their bin). Lennon was a hero to me, a man who was using his fame for purposes of good, making daring musical choices standing as a man of the people, defender of justice and champion of peace. Some Time in New York City, of course, then as now, is a terrible, terrible album, an aural nightmare of blare and cacophony, accent on phony, ugly and shrill, hectoring, bombastic, dishonest and nauseating.

It wouldn’t be hard to top Some Time, McCartney could have put out nothing but silence (which is really the only appropriate response) and still come out ahead. Wild Life, however, presents an even more extreme case of redemption. It was an outright commercial disaster when it came out; I put off listening to it for years and hated it when I finally did. I bought it only when I was able to find a copy for less than three dollars, just to complete my collection, and only listened to it once, slack-jawed in horror at its laziness, fuzziness and lack of direction. Then, just the other day I put it on again and couldn’t get over how good it sounded. All those old adjectives still applied, but now they seemed like positive attributes. Wild Life is lazy, fuzzy and lacking in direction, but compared to what became the typical McCartney product of polish, sheen and calculation it positively glistens with life and tunefulness. “Bip Bop,” a song I used to cite as the nadir of McCartney’s composing career, is now charming and delightful, “Dear Friend” is poignant, honest and revealing, and “Tomorrow” is one of his overlooked gems on a level with “Every Night” and “That Would Be Something.”

1973: Mind Games v. Red Rose Speedway

It’s hard to imagine, now, two giant superstars putting out competing albums every year. These days they could not possibly be expected to keep up the pace and not have the material suffer. And while Mind Games is a marked improvement over Some Time in New York City (recordings of weasels being tossed into a wood-chipper would be a marked improvement over Some Time in New York City), Mind Games strikes me as weak and perfunctory. Back in the day I could work up some enthusiasm for it, but even then it seemed like a pale imitation of Imagine. There isn’t anything on it as impressive as “Gimme Some Truth” or “I Don’t Wanna Be a Soldier” or “How Do You Sleep?” and Lennon’s save-the-world-ism even back then sounded naive, silly and ineffective.

On the other hand, back then I found Red Rose Speedway to be a baffling dead-end of misfires and time-wasters. Time, and lowering of expectations, has leavened my opinion of it, but it still strikes me as underwhelming and unfocused (and now I find out that it was supposed to be a double album! sheeesh!). I’m giving Mind Games the edge here.

1974: Walls and Bridges v. Band on the Run

Okay, Band on the Run came out in 1973. Sue me. (Jesus, McCartney put out two albums in 1973, and “Live and Let Die” — what the fuck is wrong with U2, R.E.M., Bruce Springsteen? Who are these poseurs?)

Back in the day, I counted Walls and Bridges “Plastic Ono Band in color,” Lennon’s masterful summation of all his obsessions, produced with care and skill, full of wit and imagination. I still like it okay, but time has not been kind to it. It now feels padded, self-conscious and, again, dishonest. I regularly skip over “Whatever Gets You Thru the Night” and have little patience for “Bless You,” “Scared,” “Old Dirt Road” and “Beef Jerky.” The big production number, “Nobody Loves You When You’re Down and Out,” strikes me as uncomfortably self-pitying and morose, everything Plastic Ono Band was not.

Beatle fans reveled in Band on the Run at the time; Paul’s career suddenly snapped into focus — it seemed like this was finally his Plastic Ono Band. I talked myself into liking Band on the Run at the time; it certainly provided more Beatlesque polish and entertainment value than anything else McCartney had put out up to that point, but it now strikes me as overhyped, overproduced and even ponderous in places. I love the title tune, “Jet,” and “Helen Wheels,” but otherwise the album seems cold, impersonal and hollow, listenable as it is.

1975: Rock n Roll v. Venus and Mars

I loved Rock n Roll back in the day, I found it bracing, fun, invigorating and vital. Venus and Mars I found cutesy, vague, self-important and annoying. What’s changed since then is I’ve heard the originals that Lennon was singing on Rock n Roll and find his production choices to be dreadfully, tragically wrong-headed. I bought the remastered CD when it came out a few years ago and couldn’t finish listening to it — it was loud, sluggish, hugely over-produced and leaden, everything the original versions of those songs were not. Ironically, or perhaps not, McCartney went on to record superior versions of many of the songs from Rock n Roll — whether this is mere coincidence or yet another backhanded attempt on McCartney’s part to degrade Lennon’s reputation is unknown to me.

My opinion of Venus and Mars remains unchanged.

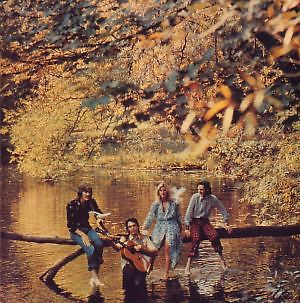

1975-1979: Lennon abstains

Lennon, as is well known, declined to record for the next five years. That would seem like a natural state of being for an artist of Lennon’s stature today, but back then it was an eternity. McCartney ran the field free of competition for those five years, releasing At the Speed of Sound, Wings Over America, London Town and Back to the Egg, all of which were more-or-less commercial smashes, in some cases mysteriously. At the Speed of Sound is godawful — whatever possessed McCartney to actually share album space with the other members of Wings? What the hell was he thinking? Did he really think this band could compete with the Beatles? How is that possible? Or did he just not have enough songs to fill an album and had to get something into the stores to promote on a world tour? In any case, this is the one Wings album I have yet to be able to listen to all the way through. Wings Over America, on the other hand, presents a compelling case for Wings as a musical statement separate from, if not quite equal to, the Beatles. London Town, an album I virulently despised when it came out, has aged surprisingly well — whenever a McCartney tune comes up on iTunes and I think “hey, this isn’t bad, what’s this?” it invariably comes from London Town. Which is not to say that London Town doesn’t contain its share of filler and dreck — “Girlfriend” leaps immediately to mind, as well as non-songs like “Cuff Link.” Back to the Egg, on the other hand, I loved immediately and is still my favorite Wings album by far. It was reviled and unpopular when it came out, which never made sense to me. I loved the weird avant-gardisms, I thought “Getting Closer” and “Spin it On” crushed, and found all the little linked songs spooky and intriguing. My opinion hasn’t changed — every time a Back to the Egg song pops up on iTunes I still feel a charge.

1980: Double Fantasy v. McCartney II

It is, of course, difficult to separate Double Fantasy from the context it appeared in — coming out days before Lennon’s murder, it took on tragic dimensions of shattered dreams and starcrossed love. I, for one, was greatly looking forward to hearing it and bought it on its release date — and was distinctly let down. Lennon’s songs felt weak, thin and slight, and Yoko’s, well, I’m going to go out on a limb here and say that, in my opinion, Yoko’s songwriting talent is not the equal of John’s. There, I said it. I could kind of work up some enthusiasm for the goofy charm of something like “I’m Your Angel” but otherwise itwas an uphill climb. Of course his murder changed all of that.

Time has not been kind to Double Fantasy. Lennon’s songs stand up well for the most part, but no agency on Earth can compel me to listen to any more Yoko Ono. And this coming from someone who enjoys “Cambridge 1969” from Life With the Lions and side 2 of Live Peace in Toronto. Still, seven decent songs on a record is still pretty good, even if some are too sappy and others are too skinny, and I would have very much enjoyed to see where Lennon was going to go from there.

McCartney II has all the sketchiness and home-made-iness of McCartney and absolutely none of its charm or delight. It is a tinny, clangorous horror, even if TLC swiped the opening lines of “Waterfalls.” “Secret Friend” goes on for a stultifying 10 and a half minutes!

Both were big hits.