Movie Night With Urbaniak: Viva Zapata!

Biographical drama is hard. The writer is faced with a number of problems — either the audience knows too much about the protagonist, which means they’re way ahead of the narrative, or else the audience doesn’t know enough about the protagonist, which means the movie has to contain all kinds of tiresome exposition to explain who everyone is and why they’re important to the story.

Movie Night with Urbaniak: Black Narcissus

Not Richard Roundtree.

I’d never seen Black Narcissus before, but it’s come up a number of times in conversations lately (as in “You’ve never seen Black Narcissus?!” or “Well, if you’re interested in Michael Powell, the place you should start is Black Narcissus.“).

I don’t know why I’ve put off seeing it, but for some reason I always thought it was another “hip,” updated retelling of a Greek myth a la Black Orpheus. Either that or a gritty 1970s Harlem crime thriller starring Richard Roundtree. (“Narcissus is back, and this time — he’s black!“)

Anyway, it’s neither of those things. It’s an early Technicolor masterpiece about a bunch of nuns who try to open a convent on a mountain redoubt in the Himalaya. It’s photography was about ten years ahead of its time and its sexual tension was at least thirty.

Essentially an allegory about British colonialism, a group of uptight, sexually repressed British nuns (are there other kinds?) led by Sister Clodagh decide it’s a good idea to open a franchise in a “wild,” “simple” land where “the men are men, the women are women and the children are children.” The free, “childlike” ways of the locals and the clear mountain air conspire to drive all the nuns a little crazy as they struggle to reign in their desires and neuroses. English civilization crash-lands on the rocks of local superstition, the local prince falls in love with the local slut, and man trouble erupts in the form of local shirtless handyman Mr. Dean. Eventually the story devolves into a horror movie as one of the nuns, Sister Ruth, proves herself to be even more tightly wound than Sister Clodagh and becomes Jack Nicholson in The Shining.

Deborah Kerr is measured and nuanced as Sister Clodagh and Kathleen Byron is appropriately high-strung as Sister Ruth, but otherwise the acting in the movie is about as broad and hysterical as it gets. British stage actors play Indians (talk about a director missing his own metaphor!) so big it’s as if they’re waiting for the applause to follow their most outrageous moments. Jean Simmons plays the Paris Hilton of the Himalaya with teeth-baring, hip-swiveling gusto. David Farrar should smolder and seduce as Mr. Dean, but instead he just kind of stands around and poses. As

notes, it doesn’t help that he looks like Kevin Nealon, if Kevin Nealon underwent plastic surgery to look more like Daniel Day-Lewis.

Movie Night With Urbaniak: Pickup on South Street

Neither

nor I have ever seen Pickup on South Street, but after The Naked Kiss I’m curious to hear his take on Samuel Fuller’s, erm, unique approach to screen acting. So he comes over and we watch the movie.

“A maddening director,” says Urbaniak. And “maddening” is certainly an apt description. You’re watching a Sam Fuller movie and you’rethinking, “this guy is so bad, he doesn’t understand the first thing about what film is,” and then out of nowhere he’ll produce some effect so daring, so creative and so sophisticated that it’ll make your head spin. And he’ll do this, mmm, about sixty times in the course of a 90-minute feature.

In Pickup there’s an actor named Murvyn Vye playing “Detective Tiger,” and there isn’t a single spontaneous, heartfelt or natural line reading, gesture or movement in his entire performance. I mean, this is a guy who looks out a window and says “He’s here,” and not only do you not believe he’s seeing anyone, you don’t believe he’s ever looked out a window before. And you despair because you’re watching a lame police drama. Then, out of nowhere, ace pro Thelma Ritter walks in, acting as though she’s in a completely different movie, and just mops up the floor with the guy. Just takes the mop handle out of the closet, screws it into the guy’s navel, and literally mops the floor with him. And just as you’re about done marveling at the great Thelma Ritter’s performance, you realize that the scene you’ve been watching has been an eight-minute long extended take, full of dollies and zooms and tracking movements, and you remember that you’re watching a movie by one of the true mad geniuses of American film.

Similarly, there’s Jean Peters as The Girl. The Girl is supposed to be a hard-nose, hard-luck dame who’s been around the block a few times, and she honestly looks like a perfectly nice young lady who’s watched a few movies. You can’t believe she’s the lead, she’s fake and flat and all surface. Then, she goes to see co-lead Richard Widmark and a weird thing happens. He picked her purse, she needs the maguffin back or its her head, and next thing you know, Widmark is putting the moves on her and she’s totally falling for him. The scene shouldn’t work on about ten different levels, but it does because Peters suddenly explodes with passion, vulnerability and deep sensuality. And suddenly a movie you could barely believe got released becomes something so intense and deeply personal that you can’t believe you’re watching it. And you realize, “that’s the audition scene,” that’s the scene that got her the part,” Fuller cast her because he knew she’d be able to sell the weirdest-ass scenes in the movie, the ones the narrative won’t work without. To give you an idea of how weird her scenes with Widmark are, imagine the famous encounter between Laura Dern and Willem Dafoe in Wild at Heart, but instead of Willem ending up with his head blown off outside a bank, Laura Dern runs off with him and it turns out he’s really a really sweet guy and a patriot to boot.

Fuller the filmmaker is no less idiosyncratic. He’ll mark time through any number of ho-hum procedural scenes, then uncork a fight scene as intense, frightening and real as anything in Raging Bull, or, conversely, he’ll ruin a beautiful death-bed monologue with an utterly unnecessary reaction shot, or spoil a love scene with a shot out of focus. It’s almost like he’s playing with you, lulling you into a false set of expectations, waiting for the next opportunity to blow your mind.

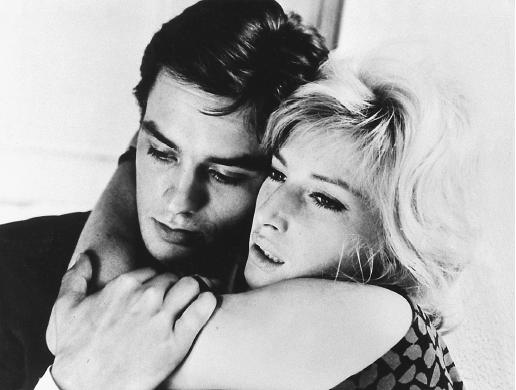

Movie Night With Urbaniak: L’Eclisse

YOUR ATTENTION, PLEASE: This post was originally at least twice as long. Somewhere in the posting of it, half of it got mysteriously eaten by some livejournal program glitch. This makes me angry, but I currently don’t have the time or energy to re-write it. Suffice to say, I liked this movie and so did

.

[beginning of original post]

You know how I mentioned last time around how L’Avventura has no plot, yet is still tremendously exciting? Well, L’Eclisse has even less plot than L’Avventura, and is even more exciting. It’s almost like Antonioni is daring himself to stretch this method of designing narratives as far as it will go.

[significant portion of post mysteriously eaten here.]

[description of first 50 minutes of the movie — Vittoria’s difficulty with relationships, her restlessness, her discomfort, her flight to Verona]

[we join the post half-way through — I am describing a rather amazing 10-minute scene set in the buzz and flurry of a bad day at the stock exchange]

Urbaniak says, “the best extra work of all time.” I mean, it’s really quite stunning, it’s a hugely complicated scene, certainly as complicated as, say, any Hitchcock suspense scene, and as exciting, but like I say, it’s even more of an impressive stunt because we have no idea what it has to do with anything.

Anyway, Vittoria’s mother is there at the stock market, as usual, but today she’s really upset because she’s losing all her money. The market takes a downturn and stays there and everyone is quite upset by the end of the day. And Vittoria shows up toward the end of the day, wondering what all the excitement’s about. She knows nothing about the market and less about crashes (“But if someone lost the money, then surely someone else had to get that money — right?” she asks, hopefully).

10. Piero points out to her a man who has lost 50 million lira in the day’s trading, a sad, overweight, bespectacled man who wanders silently out of the marketplace, and I say “it would be great if the movie now just suddenly dropped everything and followed that guy around,” which, much to my amazement, it then proceeds to do, for about five minutes. Vittoria follows him as wanders, a little shell-shocked, around Rome, much like we’ve watched Vittoria wander shell-shocked, only we know the reason for this guy’s discomfort. But it seems Vittoria sees a kindred spirit in this man who’s lost everything and doesn’t quite know how that happened. She tails him to a little cafe, where he sits down and busies himself with a pencil and paper. We think maybe he’s writing a suicide note or a letter of resignation, but when Vittoria (and we) finally see the paper, it’s covered with childish, even girlish, drawings of little flowers.

11. Vittoria takes Piero to her mother’s apartment for some reason, I don’t know why. She barely knows him, only that he’s her mother’s stockbroker (and her mother now owes him quite a lot of money). We see the room where Vittoria grew up and learn that her father died in the war and her mother is terrified of poverty. As is everyone, quips Piero, but Vittoria says that she never thinks about it. Or being rich either. And we realize that Vittoria doesn’t seem to have given much thought to anything in her future at all — she just kind of blindly gropes forward, hoping the next thing that comes along won’t be quite as much of a dead end as the last thing. She flirts with Piero, then shies away, then flirts with him again. Mom comes home, worrying about where she’s going to get the money to pay Piero — she’s already hocked all her jewelry.

12. At Piero’s office, Piero’s boss tries to explain to the workers how they’re going to get through the crisis of the next stock cycle, how it’s vital to get the money lost from the deadbeats who’ve lost it. Piero needs no coaching on this — he’s regular monster when it comes to making investors feel like losers and idiots for trusting him with their money. And like I say, suddenly we’re seeing everything from Piero’s point of view instead of Vittoria’s. And while Vittoria is vaguely unhappy and fidgety and uncomfortable with everything, Piero is a callous heel who doesn’t seem to have a thought in his head beyond eating and drinking and screwing and doing business — which is to say he’s a stockbroker.

13. After work, Piero, at a loose end, drives over to Vittoria’s place and woos her beneath her balcony (aha! So the Romeo and Juliet reference was intentional!). Why is he attracted to her? Does it have something to do with her mother owing him a great deal of money? More to the point, what does she see in him? Anything? Or is this just how she is with men, just kind of wandering in and out of relationships, not really knowing what she’s doing there, not really having the will to break away? While Piero’s chatting her up, a friendly drunk steals Piero’s pricey sports car and drives it away. This bothers Piero, but not enough to stop him from trying to get a leg over with Vittoria.

14. Next thing we know, the drunk (I think) has crashed Piero’s car and it’s getting fished out of the river. Vittoria is a little horrified by this, but Piero is only concerned about whether or not it will greatly affect the car’s resale value. Everything in the audience’s will screams for Vittoria to go far away from this cad, but she spends the afternoon wandering around the suburbs with him anyway, strolling past a number of rapidly piling up symbols — baby carriages, priests, a recurring horse-drawn cart, and most important, a half-finished new building and the stacks of construction materials surrounding it, which get treated to many disconcerting, lingering closeups.

Vittoria grabs a balloon off a baby carriage, then sends it aloft to her not-very-good friend Marta’s balcony. Marta, the daughter of the big-game hunter, obliges her by getting her father’s elephant gun and blowing the balloon into atoms.

As Vittoria tries to decide to let Piero have his way with her, she rather strangely plunges a chunk of wood into a rain barrel on the new building’s construction site. It’s an odd moment, but it gets odder still, as we will see.

15. Later that night, Vittoria calls up Piero but then doesn’t say anything when he answers.

16. Several times before the end of the movie, we cut back to that chunk of wood in the rain barrel. I don’t know why, but apparently the chunk of wood means something. Is it Vittoria’s soul? Are we checking to see that her soul is remaining afloat? Or is it hope that floats? In any case, the chunk of wood starts to take on significant emotional significance. We want to shout out “go chunk of wood! float! float! float!”

17. Vittoria allows Piero to take her up to his place. Piero is just as big a heel in his own apartment as he is in public. Even though he grew up in this apartment, he has no connection to anything there and seems to have no inner life. He’s decorated the place in cheap bachelor-pad decor and keeps his supply of nudie novelty pens in the study. To underline the metaphor succinctly, he offers Vittoria a chocolate from a box, but when he opens it he finds that the box is, in fact, empty.

Vittoria and Piero fidget around in this apartment, trying to figure out how to start this love affair the two of them apparently want to have, not knowing quite how to do it. The sequence is almost as long as, and serves as a bookend to, the first scene with Riccardo — there, Vittoria was stumblingly trying to figure out how to leave a guy, here she’s trying to stumblingly figure out how to get together with one. “Around you I feel like I’m in a foreign country,” she says, and we know exactly what she means. To make his point succinctly, Antonioni has their first kiss happen through a pane of glass.

The tag line for Annie Hall was “A nervous love story,” but that fits L’Eclisse even better. Both of these beautiful young people are absurdly nervous about something — love or “the world” or something, I don’t think they know. I think Antonioni knows, but I don’t think he wants to tell us — that would somehow ruin everything.

They apparently finally get it on, and Vittoria, for a moment or so, seems happy. Why, we don’t know.

18. Then — crisis! The rain barrel leaks, spilling its water into the street and down the gutter. The camera lingers on this for a long time, the water gushing out of the rusted barrel, Vittoria’s special chunk of wood, her stick of hope, swirling around helplessly as water level drops.

19. Then, as a denouement, some buildings, some faceless people wandering around the cold, modernist, characterless suburb, and a curtain call of symbols. The baby carriage again, the priest, the horse and carriage. A sprinkler is shut off. A modernist streetlamp comes on. There’s that building again, with its heaps of unused construction materials. A man gets off a bus carrying a newspaper — the headline is something like “ARMS RACE SHOWDOWN” and “A NUCLEAR SHADOW,” which almost ruins the whole movie. It’s like Da Vinci writing at the bottom of the Mona Lisa, “She’s smiling because Italy has justemerged from a thousand years of church-dominated ignorance.” Does the H-bomb account for Vittoria’s discomfort, for Piero’s callousness, for the stock-market crash? Is that what the movie is finally “about?” Or is the nuclear threat only a symptom of something else, something harder to put one’s finger on? Because these answers are harder to come to, ultimately I think L’Eclisse is a more daring and accomplished movie than L’Avventura — Antonioni here really seems to be on the verge of something profound. This is tough, unsentimental, rigorous, hugely disciplined filmmaking, with the highest of artistic aspirations — no wonder the purists are so upset by Blow-Up, which is stylish, superficial and glib in comparison.

In the closing moments of the movie, a jet plane flies overhead. The sound-effect geek in me cannot help but note that the “jet plane” sound used is the exact same recording heard a few years later at the beginning of The Beatles’ recording “Back in the USSR.” Coincidence or incredibly-obscure homage? You be the judge.

Movie Night With Urbaniak: L’Avventura

The first thing you need to know about L’Avventura is that it has no plot. The second thing you need to know about L’Avventura is that, in spite of having no plot, it is still tremendously exciting.

I don’t know how it manages to do that.

This was a rare instance of

actually requesting a movie to watch, rather than the two of us just kind of pawing through my DVD collection until we find something we both want to watch. He showed up with the movie clutched in his slender, spidery, indie-stalwart hands, still it its shrinkwrap, still with the price tag from Amoeba on it.

The movie is loaded with symbolism, but the characters aren’t symbolic — they’re real people. At least I think they are. Every time I tried to read the movie as purely symbolist it would answer with a scene that said that it was actually a character study.

Come to think of it, the story structure kind of reminds me of Raymond Carver. It’s not about big moments, or about a coherent dramatic arc. It’s about these people caught in a situation and it kind of sits there and studies how the people behave. And all the incidents that make up the narrative are all really small and not necessarily significant in and of themselves, but are so specific, and so ineffably cliche-free, they retain our interest. We keep watching partly because we want to know why the people are doing the things they’re doing and partly because we want to know why the filmmakers chose to shoot the scene. What do all these little moments of behavior add up to? Will the trashy celebrity who shows up in Act III show up again in Act IV? Why this town, why this church, why this shirt, why this room, why this hour of the day? Resonances and echoes show up all over the place (just like they show up in that scene with the church bells) and every time you think a scene isn’t going anywhere the scene goes somewhere, but never where you thought it was going.

In other ways, the story structure reminds me of Kubrick, in that there are long slabs of narrative dedicated to illustrating one plot point and we don’t know what the plot point is until we arrive at it at the end of the slab. Those slabs are, roughly:

1. Let’s go on a cruise! (30 min)

2. Looking for Anna (30 min)

3. Will Sandro get a leg over? Will Claudia give in? (30 min)

4. Claudia commits (30 min)

5. Crisis (17 min)

1. So there’s this woman, Anna. She’s young and Italian in 1960. She was probably a child during the war. Her father is a builder of some sort. We first see her have a halting conversation with dad in front of one of his building projects. He’s tearing down some old buildings to put a new one there.

says that’s a major theme of the movie: destroying down the old to make way for, what, exactly? The anxiety of that question hangs over the entire narrative.

Anna’s in love with Sandro. Or maybe she isn’t. Claudia is in love with Anna. Or maybe she’s in love with Sandro. In any case, there’s a lot of unspoken tension between the three of them. Maybe Anna isn’t really happy with Sandro and would rather go with Claudia. Maybe the opposite is the case.

This bunch of funsters go on a cruise in the Mediterranean with some friends. Their friends’ relationships are, to put it mildly, dysfunctional at best and doomed at worst.

Theyarrive at an island. Folks go swimming, folks climb on rocks, folks bicker.

2. Somebody notices Anna isn’t around any more. The group searches the island. They call the police. The police and whatever authorities do things like this search the island. For 30 minutes we watch people climb over rocks and gaze into the water and wonder what the hell happened to Anna. Because either she’s hiding, which is unlikely, or she’s unconscious somewhere we haven’t looked yet, or she’s dead somewhere we haven’t looked yet, or she got on a boat we didn’t see and rode off somewhere. If she’s dead, she could be dead by suicide or by murder or by accident.

3. Apparently Anna is not on the island and nowhere near the island. The other couples go on with their vacation while Claudia worries about Anna and Sandro half-heartedly searches a nearby town. I say half-heartedly because, well, for some reason Sandro, now that Anna is gone, doesn’t want to waste the opportunity to make a move on Claudia. Claudia is horrified by Sandro’s advances — her friend-girlfriend -Sandro’s-girlfriend is missing and she feels guilty and terrible about it — this is no time to be messing around the ancient, tumble-down towns of rural Italy.

The narrative starts to splinter here as Sandro gets distracted and Claudia gets anxious. Sandro runs into that trashy celebrity mentioned above, Claudia gets caught at a society gathering refereeing for her non-friend Giulia’s (or is it Patrizia’s?) makeout-session with a Bob Denver-lookalike teenage artist, whose paintings are an affront not just to the beauty of the villa where he’s staying but an affront to their subjects and to the act of painting itself.

4. Claudia suddenly, and without preamble, gives in to Sandro’s advances and declares herself desperately in love with him. Maybe she’s been in love with him from the beginning, maybe she’s just recently decided she is, maybe she’s fooling herself. We know Sandro is a lout who has no idea what love is, that seems clear enough, but Claudia seems to be cut from different cloth. First, she’s the only one on Team Ennui who wasn’t born wealthy, second she’s the only one who carried any sense of guilt about Anna’s disappearance all the way through Act III. This is where I started to think L’Avventura is about postwar Italy, how a new generation chose to move ahead into some ill-defined bright tomorrow while others couldn’t help but feel a sense of guilt and loss for what had been destroyed in the war. In any case, loss, the careless destruction of the old and beautiful, the replacement of the old and beautiful with the new and ugly (and profitable) is one of the movie’s ongoing concerns.

griped toward the beginning of the movie that he didn’t like the actor playing Sandro, that he was uninteresting and shallow, giving a kind of generic “60s leading man” performance. By the end of the movie he had changed his tune, realizing that the actor was not giving a shallow performance, he was performing the action of being shallow, which is a completely different thing. That is, it’s not the actor who is giving a generic “60s leading man” performance, it is Sandro who is giving it. As Act IV goes on and Sandro starts to reveal his true ugliness, shallowness and restlessness he becomes infinitely more interesting. Conversely, Claudia, once she gives up on honoring Anna and gives in to Sandro’s indelicate advances, becomes slightly less interesting as she pines and swoons and tries on different outfits.

Why does Claudia fall for Sandro? We don’t want her to. If she always had a thingfor him, she’s an idiot, and she doesn’t seem to be an idiot. I prefer to think that both Sandro and Claudia had a thing for Anna and when Anna vanished she created a kind of relationship black hole that sucked Claudia and Sandro toward each other. Claudia becomes attracted to Sandro because they now have something in common — missing Anna.

Let’s say for the moment that Anna is a symbol for something really pretentious like “the soul of Italy.” The soul of Italy has vanished and only Claudia seems to really care about any of that. Sandro doesn’t care — he made his peace a long time ago that he wasn’t going to create anything beautiful. He had his chance — he coulda been a contender architect, we learn at one point, but gave it up for the short-end money. Then we see him knock a bottle of ink over onto a drawing someone’s making of a gorgeous church window. Sandro cares about the soul of Italy insofar as he wishes to destroy it as quickly as possible. To replace it with what? Well, that’s where Sandro’s anxiety comes in. He doesn’t have any idea what he’s going to replace it with. Maybe that’s why he makes such a fast move for Claudia — he’s just reaching out for the nearest available object to replace the hole in his soul that opened up when Anna disappeared.

5. Sandro and Claudia, having declared their undying love for each other, check into a hotel where their friends are staying. There’s a big party going on. Claudia is tired and wants to stay in the room, but Sandro gets duded up in his tuxedo to check out the action. Claudia can’t sleep and mopes around the room while Sandro wanders, bored and restless, among the empty suits and fashionable gowns. He sits down to watch a TV show in the hotel TV room. We don’t see what’s on TV, but it seems to be a show primarily about things that go “WHOOOSH!” He watches this scintillating program for a few seconds before wincing at it and moving on.

Claudia suddenly has a vision that Anna has returned, which she feels would be really bad at this point because it means that her love with Sandro would be doomed. She rushes downstairs to the empty ruined ballroom and finds Sandro making out with the trashy celebrity from Act III.

Claudia dashes out of the hotel, as one does in situations like this, and Sandro chases after her. (The trashy celebrity begs Sandro for a “souvenier” and he disgustedly throws a wad of money at her. She lazily gathers it up with her bare feet like an octopus capturing its prey.)

Sandro collapses on a bench and cries. Does he feel something? Is he worried about losing Claudia? Is he mourning Anna? Is he mourning his own soullessness?

Claudia approaches. A satisfying ending would be: she hits him with a big rock and screams “I KILLED ANNA AND ATE THE BODY, YOU FOOL!” But that’s not what happens. She should, at the very least, be very angry at him — he went pouncing off after Paris Hilton mere moments after declaring his unending love for Claudia — and did so while Claudi was right upstairs! But we watch as she balances that anger for a moment, as she literally balances her own self, gripping the back of the bench to keep herself upright. Then she places a hand on Sandro’s shoulder, as though to forgive him, then, incredibly, she moves her hand up to his head, to pull him to her, to comfort him. We have no idea what happened to Anna, all we know is she’s gone and, as far as the movie is concerned, isn’t coming back.

(Idea for sequel: L’Avventura II: Anna’s Return!)

And then the last shot, reproduced above. Half mountain, half ruined building, the wounded, conflicted, embattled couple facing their uncertain future. “The ‘adventure,'” says

, is the couple’s adventure into adulthood.” “And Italy’s adventure into the future,” I add, half-heartedly, because I’m really not sure.

Movie Night With Urbaniak: Close Encounters of the Third Kind

There are movies and there are movies.

I’m a Spielberg fan. I’ve been a Spielberg fan for a long time.

How long have I been a Spielberg fan? I’ll tell you how long I’ve been a Spielberg fan, smart guy. When Duel came on the television machine in 1971 and I was ten years old, I remember I wanted to watch it because it was directed by the guy who had made a Columbo episode I really enjoyed (which IMDb tells me was broadcast a mere two weeks earlier.)

I loved Jaws, it changed my life, no doubt about it, but my confidence in Spielberg as the leading director of his generation was already well in place in my mind by the time Close Encounters opened in theaters, Christmas 1977.

I was, at that point, a 16-year-old usher who had just gotten a job working at what had once been a vaudeville house in the suburbs of Chicago. The first movie during my tenure there was Close Encounters, so I was blessed to see this movie thirty or more times in its initial run, with a crowd every night, and it never got old, never wore out its welcome, never seemed like anything less than an event. A symphony.

The truck on the lonesome highway, the police-car chase, the perfectly-observed scenes of casual suburban squalor, the attack on the country house, these are scenes I would race to the theater to watch over and over, marveling at them anew each time. I’ll tell you: I knew from the first that Close Encounters was great cinema, but somehow it’s never felt to me like Close Encounters was “show business.” I always felt, from the very beginning, and this goes for a lot of Spielberg’s movies, that I was watching something that transcended “show business,” that I was in the hands of a true believer. It hit me relatively early on that Close Encounters was a deeply religious movie, and the notion of godlike, benign extraterrestrials showing up and extending an innocent, questioning hand of greeting to our horribly wrong-headed world was one I found hugely seductive and almost unbearably moving.

God calls, and Roy Neary answers. God calls many people, but only Roy Neary has what it takes to push through all the bullshit in the world, the trappings of his stupid bullshit suburban family life, the chains of work, reputation and normality. Only Roy Neary has what it takes to answer the call, leave his life, make it through all the barriers that this awful world puts in his way (the government, who has also heard God’s call, desperately desires to exclusively control the discourse between humanity and the deity) and step up to the altar to be received into heaven. It’s a profound statement of faith, fortitude and perseverance.

I have no idea how it plays now. I’ve watched it so many times it barely feels like a narrative tome any more, it flows so naturally and so effortlessly. I can see the craft and care put into it, but I also still get utterly lost in its most powerful scenes. One day, when I show it to my children, will they see the same movie I saw at 16? Or will they look at the clunky 70s special effects, the gritty 70s-realism acting and production design, the low-key, humanistic story line and be all like “o-kay, Dad, whatever you say, is it okay if we go upstairs and watch Transformers III again?” Will they have to wait until they learn a little something about film history before they will be affected by its rhythms, its layers of references, the purity of its soul?

Anyway,

and I watched it tonight over a bottle of pretty good wine and it was a blast. The air-traffic-controller scene toward the beginning of the movie, a scene that would be cut from any other movie today, stuck out for us immediately. I’ve always loved the scene and found it terrifically exciting, especially for a scene involving none of the principle characters, no special effects, and no on-screen confrontations. It’s a scene about a bunch of professionals talking on radios and yet somehow the tension is palpable. The acting in it is not only some of the best in the movie but some of the best in Spielberg’s canon. In a lot of ways, as Urbaniak mentioned, it’s hard to imagine Spielberg today directing that scene. It’s like a scene from All the President’s Men or something, all subtlety and nuance, the performances deriving their power from what the characters are not saying, not what they are saying. And the voice work of the radio voices could not be better.

Someone, I can’t remember who, once asked, regarding the opening scene, “Why doesn’t the UFO investigation team wait for the sandstorm to end before they go out into the field?” And it’s a good example of the pure cinema of this movie. The UFO investigators go out into the Mexican desert in the middle of a sandstorm because it makes a better scene — it creates pressure and urgency. These guys aren’t just investigating UFOs, they’re investigating UFOs in the middle of a sandstorm, which means they have to shout and cough and gaze in wonderment at things that appear mysteriously out of the sandstorm.

Compare this scene with the “Mongolia” scene shot for the otherwise-useless “Special Edition” from 1980. The Mexico scene in the original is weird, mysterious and deeply unsettling, the Mongolia scene is jokey, obvious, shot and cut in a completely different style, closer to an Indiana Jones movie in tone than Close Encounters. I like the idea of the scene but, basically, I can find no shot in the “Special Edition” that improves my understanding of Close Encounters and it gave me great heart to realize that Spielberg had expunged most of it for the current edition on the racks.

Now that I am sufficiently removed from Midwestern suburban life of the 1970s, I gaze upon the production design of Close Encounters with something approaching awe. The hell with the UFOs, I want to know who was responsible for the astonishing set-dressing of Roy Neary’s house. You can tell that Roy has gotten his “one room” to decorate, it’s the one with the milk crates stacked against the wall for shelving and the hobby crap piled up everywhere. But what about the rest of the house? All the tschotchkes and bric-a-brac, the Walter Keene painting over the piano, the ceramic chicken on the “good china” shelves, who picked all that out? Ronnie? She’s 30 years old, she picked out all that crap? How did she ever have the time? The house is full of crap, the stupid prints hanging in the bedroom, the ungodly wallpaper, the Snoopy poster in the boy’s bedroom, the mismatched glassware, the milk carton on the table at dinnertime, the casual blurring of personal boundaries, everything is absolutely godawful, everything is absolutely accurate, and everything is mounted with such great love and understanding of those characters and their world, and, best of all, it’s never pointed at by Spielberg. Spielberg never holds up these suburbanites as ridiculous, he loves these people and wants to capture their world with all the detail he can muster.

Movie Night With Urbaniak: Yukoku, Z

Two political thrillers of extremely different stripes this evening. The first, Yukio Mishima’s short 1966 film Yukoku and then Costa-Gavras’s 1969 political thriller Z. The two movies could not be more unalike: Yukoku is brief, stark, weird, highly stylized and almost freakishly intense, Z is naturalistic, frenetically shot and edited, alarming and intensely furious. The fact that they were made around the same time and come from polar opposites of the political spectrum make the evening that much more fun.

Yukoku is based on a short story published in the US as “Patriotism,” which is essentially a dry, clear-eyed, blow-by-blow account of an army officer committing seppuku. The movie is much more stylized, artsy even, with its abstract sets, lack of dialog and dramatic lighting. The officer comes home, greets his wife, explains the situation with her, she agrees to also kill herself, they have serious, intense, dramatically-lit sex, he gets dressed and kills himself, she goes and puts on fresh makeup, then comes back and kills herself too. A lot of Mishima’s key themes are distilled into this 25-minute movie — the changing nature of Japanese culture (which Mishima despised, being politically conservative in the extreme), the importance of dying while still beautiful, the tying together of sex and death and the compulsion to make one’s death a work of art. (Of course, most people these days watch Yukoku, if they watch it at all, because Mishima later killed himself in a manner startlingly similar to what he does in this movie.)

Mishima, surely one of the most egotistical men of his day, strangely declines to give himself a single close-up in this most personal of stories. Instead, he hides his face behind the bill of his army hat through the whole movie, giving all the close-up time to the actress playing his wife. She becomes, essentially, the protagonist of the movie — the army officer remains opaque and unknowable, while his wife (and by extension, we) are meant to fall desperately in love with his noble honor and tragic beauty. After her husband dies, the wife goes to freshen up and there is a terrific shot of her silk robe dragging through the pool of her husband’s blood on the floor. On the one hand, one says “ick,” but on the other hand, the shot drips (sorry) with symbolism and beauty, which kind of sums up my feelings about Mishima in general. On the whole, I’d rather he go on making experimental films instead of killing himself in a meaningless political gesture, but then I probably wouldn’t be sitting here thinking about him.

Z is a whole different kettle of fish.

Here in the US, we’re completely comfortable watching movies about Russia or Italy or Spain and seeing American actors speak English with cheesy accents — we don’t think a thing about it. But when watching Z, it’s disorienting for a while because it’s a movie set in Greece about Greek people but is shot, um, somewhere that’s not Greece (I think French Morocco), starring an all-French cast speaking French. On top of that, the filmmakers have made the decision to not try too hard to make their locations look authentic, which means that it feels like all you need to know is that it’s a political thriller that takes place in some sunny country. (At the time of course, the story was not only fresh but still going on, so none of this had to be explained to anyone.)

For the first half, it’s a political thriller par excellence, shot with such verisimilitude as to be startling and confusing. Nothing is explained, nothing is slowed down for the newcomers or Americans. There’s some kind of country, and it’s run by some kind of quasi-fascist regime, and an opposition leader is coming to town for a rally. We see the rally organizers trying to nail down the specifics of their upcoming event, we hear that there is a threat of assassination in the air, we see the general political unrest in the streets. We (at least we in 2007) don’t know which side anyone is on, who to root for, or even who the protagonist is. We’re just kind of plunked down in the middle of this situation and left to fend for ourselves. The shooting is all documentary style, handheld cameras and whipcrack pans, with a few artsy little flourishes, and then just when we’re getting oriented to who’s who and what’s at stake, the opposition leader gets assassinated and the movie changes gears.

53 minutes into the narrative, the protagonist shows up, the special prosecutor hired toinvestigate the assassination, and the movie becomes a detective thriller as we watch the prosecutor gather evidence, track down leads, and piece together the chain of events that led to the assassination. It’s almost unbearably thrilling, because we are in the exact same situation as the prosecutor — we just got here, we saw everything happen but we have little idea what any of it means. So as the scope of the conspiracy becomes clear and the stakes rise, our anger towards the people responsible gets greater and greater.

I first saw this movie in 1981 or so and thought “Wow, fascinating, what interesting places these horrible little tinpot dictatorships are,” and last night, of course, James and I could not help but be reminded of what our country is going through right now. We watch as government officials edit intelligence reports to fit a pre-decided outcome, twist and distort language to serve ideological ends, smear, intimidate and destroy their political opposition and finally kill anyone who disagrees with them, banning the use of language itself when it contradicts the official viewpoint, and it’s like being granted a backstage view at the White House. Halfway through the movie, I had a vision of the 28-year-old Dick Cheney watching this movie in 1969, watching how the fascists operate and whipping out a notebook, nodding along, saying “uh huh, got it, good, oh that’s a good one, yes, ah yes, indeed.”

Late in the movie the prosecutor is delivering his findings to his government superior, who grows increasingly upset as the story is accurately assembled before his eyes. The prosecutor, who has no agenda other than finding out who done it, turns up his palms, almost apologetically, and says “these are simply facts,” which is, of course, why his boss is so upset, and which is why the scene resonates with us so strongly today. We live in a country where the simple stating of facts is considered a dangerous left-wing attack on the government.

The fascists of Z despise modernism, long hair, rock music, liberalism and lack of respect for the government. One wonders whose side Mishima would have been on while watching the movie.

Movie night with Urbaniak: Performance

Neither

nor I had ever seen Nicholas Roeg’s 1969 druggy, draggy landmark of 60s Weird British Cinema before, so we were on equal footing for this viewing.

Myself, I’ve come to believe that the cinematic form demands a certain complexity of plot. Others, obviously, disagree. In any case, I’m always keeping my eye out for novel plotlines, so I kept a pad of paper and pen handy to record the plot of Performance. Here’s what I wrote:

“Chas is a cockney gangster in the 60s” (James Fox is quite startling in this part, seamlessly playing a snide, brutal thug, not unlike Michael Caine’s gangster roles of the same period, and looking a lot like Paul Bettany in Gangster #1 (which is set in the same time period).

“He gets in trouble with his boss and has to go on the lam. He scams a room in a creepy dive, a townhouse that happens to be owned by a guy named Turner, who used to be some kind of pop star.” (Turner is played by Mick Jagger, who is always fascinating to watch, but the part is drastically underwritten, I’m guessing intentionally so, to keep him enigmatic and weird.)

That’s Act I, and it’s straightforward enough. The editing is, to my taste, a little show-offy and grating, but up to here it’s still pretty much a 60s Cockney Gangster Movie (this genre would be revived in the 80s by movies like The Long Good Friday and Mona Lisa, and in the 90s by Guy Ritchie, whose movies had show-offy editing of their own).

(One of my favorite things about Cockney Gangster Movies is that everyone freaks out whenever someone pulls out a gun. You, essentially, have Gangsters Without Guns, because guns are a relative rarity in Britain. Here in the US, it’s assumed that all gangsters (at least in movies) carry guns at all times, but when a Cockney Gangster pulls out a gun, everyone hits the deck — watch out, he’s got a gun! No “Mexican Standoffs” for Cockney Gangsters, it’s all punch-ups and thrown chairs. At the climax of The Long Good Friday, Cockney Kingpin Bob Hoskins goes to war with somebody or other, calls his guys to his HQ, and passes out guns — “okay boys, here you go, come and get ’em.” Imagine Al Pacino in Scarface having to supply his thugs with guns at a special meeting.)

At the end of Act I, Chas dyes his hair red and puts on sunglasses and a trenchcoat, and begins to look disturbingly like David Bowie in 1975 (which I’m beginning to think is not a coincidence — that was the year Bowie performed in Roeg’s similarly plotted The Man Who Fell To Earth).

Act II

“Chas tries to figure out what the hell is the deal with Turner.” Turner himself is uncommunicative to the point of opacity, but he has a couple of birds who live with him who are more than happy (delighted, even) to share their secrets with him. They wander around the house, take baths, take drugs, dress up, have sex in various combinations, talk about philosophy, essentially lead a burnt-out late-60s version of the hippie dream. Turner, we eventually find out, used to be a pop star but has lost his inspiration, is looking for something new. “A time for a change,” says Turner, over and over, quoting Mick Jagger, who happens to be playing Turner. There’s a child, I don’t know whose, who also lives in the house. Turner wants Chas out, but then decides to let him stick around.

Act III

“They try to fuck him up — why? Chas freaks out.” Turner’s girlfriend feeds Chas a psychedelic mushroom. Chas has a bad trip. The themes of Act II are pushed to their abstract extremes. Incident drops severely as Chas’s concerns turn within. And I have a confession to make: I have about as much patience with movies that try to describe altered states of consciousness as I do with people who try to describe altered states of consciousness.

Anyway, Chas freaks out for a long, long time, and then, just when the movie has lost all semblance of form, it bursts through into a weird, four-minute musical number where Mick Jagger, now made up as a Cockney Gangster, sings “Memo From Turner” to Chas and his Cockney Gangster Pals, backed by the able Rolling Stones. The scene makes no sense in any way I feel like trying to discern, but it is electrifying, and I’m guessing it was inserted by studio people who said “What? You’ve got Mick Jagger in your movie and he’s not going to sing? Then what the hell is he doing there?”

“Chas’s pals come and get him.” Because the movie has to end somehow. Chas’s pals find out where he’s hiding (he doesn’t make it very hard for them) and show up. And there he is, now wearing a chestnut wig and hippie clothes, looking less like David Bowie and more like a member of Spinal Tap. It’s the Lord of the Flies moment, where “order” is suddenly restored and we see how far gone the protagonist is.

But the movie isn’t quite over yet. Something happens between Chas’s pals showing up and Chas (or someone, it’s not clear who) getting in the car with them. Someone shoots someone else in the head, someone winds up dead in a closet, someone else is shown covered in blood in an elevator. I’m not trying to keep a secret here, I honestly have no idea who’s doing what to whom.

The End.

TODD: So, I’m sorry, wait — I have a question. What just happened there?

JAMES: (Cockney accent) Well, it’s about identity, innit?

James, I will have to say, got a lot more out of this movie than I did. He recognized that it was saying something about its time (the 60s), and how the world seemed to be exploding with all these new avenues of psychological and spiritual investigation, and here’s two guys who are coming to the end of that decade from two different directions, the gangster on the lam symbolizing the “establishment” and the burnt-out pop star representing “bohemia,” and they’re both stuck in this purgatory-like house, their lives on hold as they try to figure out where to go now that all the rules have been suspended. And it’s true, the movie does do that. I just wish it would have done it with more plot.

Movie Night With Urbaniak: The Lady From Shanghai

I was, until last night, completely unfamiliar with The Lady From Shanghai. Mr.

wanted to see this 1947 Orson Welles picture for the performance of Glenn Anders, who plays a giggling, weird, creepy heavy, and I was interested because I haven’t seen enough Welles.

When James comes over for movie night, silent contemplation is not the order of the day. The two of us essentially talk through the movie, discussing the various performances — what the actor seems to have been told to do, how he or she deals with challenges of the scene and larger narrative, how his or her makeup works (or does not), what he or she seems to be striving for and how he or she achieves his or her goal or falls short.

Welles movies are great to watch in this regard and The Lady of Shanghai in particular has a peculiar assortment of performances in it. Everett Sloan and Glenn Anders seem to be in one movie, nominal star Rita Hayworth in a second, and Welles in a third. They’re even lit and made up differently, so that when Welles cuts from one to another in the midst of a dialog scene, one’s face will be shiny with sweat while the other’s will be given a matte finish, one will be lit with a distorting, grotesque light and the other will be lit like a movie star. The performances are all good, but sometimes seem to literally be taking place in different movies. How much of this is intentional I have no idea.

Whenever a performance as odd as Anders’s comes along, I, crouching under my screenwriter hat, must stop and wonder what the director was after. In this case, I think Welles directed Anders to be so strange and unsettling in order to distract from the big reveal at the end of the movie, which, if you’ve seen a few noirs in your life, isn’t that big a reveal.

The only really bad performance is Welles’s — he’s miscast in a part that is a genre type, the homicidal, simple-minded “big lug” who’s bound to be manipulated by the smarter, cannier society folk who have a use for him. On top of being obviously “too smart” for the role, Welles puts on a distracting, phony-baloney Irish brogue that somehow makes him sound more like The Brain than himself. It’s a very “technical” performance, full of all sorts of wonderful tricks and intellectual nuances, designed to draw attention to the actor’s proficiency than an emotional truth.

Whenever I watch a Welles movie, I cannot help but be reminded of the Coen Brothers. They have similar outlooks on acting and have no trouble finding (or creating) contexts for all manner of oversized, twisted, exaggerated performances. Somehow, they have been able to spin gold out of this outlook in a way Welles, another cinematic visionary, never could. The Lady of Shanghai could have easily been a Coen Bros movie, an eclectic noir with indelible characters, a skewed point of view and a twisty, unpredictable story.