Quintet

Perhaps Robert Altman’s least-popular movie, it turns out it is neither as inscrutable nor as unwatchable as many have claimed. It falls amid several different genres, including Science Fiction, Futuristic Dystopia and Apocolyptic Fantasy. And it observes,in its own way, many of the conventions of those genres.

In a world overtaken by an ice age, Essex (Paul Newman) comes to The City with his pregnant woman-child mate. He’s looking for his brother. His brother is a professional gambler, making his living at a game called Quintet, which looks like a cross between chess, backgammon and Sorry! Since the world has ended and all, the only economy the City has is this game.

Brother welcomes Essex and Pregnant Woman-Child and the family sits down to a friendly game of Quintet as Essex goes out shopping for firewood. The game barely gets underway before an assassin rolls a pipe-bomb into the apartment, killing everyone, and the movie, like many Futuristic Dystopia movies, becomes a murder mystery. Essex must find out why his family has been killed, and his investigation of this peculiar game and the high stakes its champions play for form the rest of the narrative.

It’s sluggish, partly because the characters wear bulky costumes and must either trudge through snow or walk carefully, gingerly over frozen surfaces. It is occasionally heavy-handed, if not pretentious. But it is by no means baffling, inscrutable or even especially confusing. I know that doesn’t sound like an especially ringing endorsement; the movie does have its flaws. The stars, including several excellent actors, wear silly-looking sorts of retro-futurist medieval-renaissance outfits and talk in a stilted, elevated style of speech that doesn’t provide much of the celebrated Altmanesque multi-layered dialogue or sense of life and spontaneity. The game of Quintet is never explained except in the loosest, most metaphorical sense and there isn’t much pulse to the mystery-solving aspect of the narrative.

Altman is trying to say something about the importance of ritual to a culture and the ultimate price for clinging to that ritual. The game is supposed to be a metaphor for any number of cultural rituals, from religion to warfare to politics. I think.

The real star of the movie is the setting, which, like all of Altman’s work, has been given a great deal of attention and layers of detail. In thiscase (a short documentary included with the DVD explains), the crew was granted permission to shoot on the site of Expo ’67 in Montreal in the wintertime. They adapted the fairgrounds to their own purposes and then sprayed the whole thing down with water every day, creating incredible cascades of ice and snow that permeate every room of every set in the movie. The effect is stunning; it presents a claustrophobic, run-down, derelict, haunted, futuristic city you can truly believe is the last outpost of a dying race. Indoors and outdoors, in atriums or hotel rooms, ice and snow choke stairways and cascade from light fixtures and railings. This is no set with fake snow and plastic icicles — in every scene you see the actors’ breath. Altman fogs the camera with Vaseline to make it look like the whole movie is perhaps shot through a lens of ice.

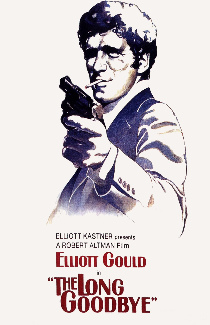

The Long Goodbye

First of all, look at these images.

The first three are different poster designs from the original release of the movie (the second one, which you may not be able to see well, is drawn by Jack Davis, is styled as a Mad Magazine parody splash-panel, and can be viewed larger here. ). Presumably, MGM owns the rights to the first three images. Yet they chose the utterly anonymous, point-of-viewless, unemphatic final image for their current DVD release. (Note: for the DVD cover, they Photoshopped a gun into the character’s hand so we would know this is a detective movie). The mind reels.

Many questions flit through my mind while watching this movie, some of which relate to the above posters.

Is this a parody? The Jack Davis poster seems to want to sell it that way. “Come see this movie, it’s a self-conscious take-off on old-timey detective stories!” But the movie doesn’t feel like parody to me, or even a comedy. It feels very much of its time and place, but it seems structured very much like a detective movie to me.

Is Elliot Gould parodying Phillip Marlowe, or merely updating him, translating him, as it were, for a new generation? The only thing I can tell for sure is that he’s not imitating Humphrey Bogart, which would have been the exact wrong thing to do in any case. But who is Phillip Marlowe in the novel (which I have not read)? Does he wander around LA with a fuzzy, jazzy interior monologue running, acting like a dissolute smartass so that people won’t know how smart and moral he is? (This performance really sticks with me, and matches the rhythms of LA so well that it’s hard not to hear him muttering his off-kilter, offhand observations as I drive around.)

I’ve read many people talk about how Gould’s Marlowe is an anachronism, how he’s this forties guy wandering around confused in a 70s LA, but he doesn’t feel anachronistic to me. He’s in a strange position because he’s not an aging hippie and he’s not an uptight businessman, he’s somewhere in between. Outwardly he judges no one (“It’s okay with me” is his comment on every fresh indignity he encounters) but inwardly he’s keeping notes, making connections and, when push comes to shove, judging quite harshly indeed. Isn’t that Phillip Marlowe?

For that matter, did “Phillip Marlowe” ever really exist? Or anyone like him? The character that Chandler’s audience read, and Bogart played, did that make total sense to readers and audiences of the time, or was he a fantastic concoction even then, like James Bond in the 60s, Shaft in the 70s (or Columbo for that matter), Buffy the Vampire Slayer in the 00s?

In many ways, it seems like this movie is the missing link between The Big Sleep and The Big Lebowski. A lot of the same characters from Lebowski are here, and The Dude in many ways seems like the logical extension of Gould’s work. I wonder if, given 30 years time or so, Lebowski will seem less like a parody and more like an unconventional-conventional detective story as well.

Casting notes: seeing Sterling Hayden in a beard playing the alcoholic, washed-up writer reminds me that he was originally cast as Quint in Jaws. His performance here gives a tantalizing glimpse of what that might have been like. And a young man named Arnold Schwarzeneggar plays a nameless thug working for Jackie Treehorn Marty Augustine.

Robert Altman

Well, I couldn’t let the day go by without mentioning the passing of Robert Altman.

He had a gigantic filmography with all kinds of stuff in it. 87 directing credits, including anonymous TV piecework, a decade’s worth of adaptations of American plays, some bizarre (and failed) experiments, some charming frippery, a few expensive studio misfires and probably twenty or so visionary masterpieces of American cinema.

If you’ve never see MASH, or only know the material from the insipid TV series, do yourself a favor and see the original. It will blow you away. It’s profane, hilarious, bloody, shocking, electrifying and defiantly frank in its depiction of the human condition.

Altman could be distressingly erratic but his successes were so definitive and inspiring that they always made up for his failures. You could sit through a dud as hapless as Beyond Therapy knowing that, sooner or later, he would come back with a superior entertainment like The Player or the flat-out masterpiece Gosford Park. Eclectic, prodigious and up for anything, his unpredictability made him relentlessly uncommercial but also gave him the most daringly alive career of any American director.

I am dismayed to find that I have only seen 17 of his movies: Countdown, MASH, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, California Split, Nashville, Buffalo Bill and the Indians, Popeye, Streamers, Fool for Love, Beyond Therapy, Aria, The Player, Short Cuts, The Gingerbread Man, Cookie’s Fortune, Gosford Park and The Company. As I peer over this list, I find six staggering masterpieces, one expensive, fascinating failed experiment, five worthwhile but lesser works, one atrocity and two mainstream studio pictures that could have been directed by anyone (both of which were, by the way, commercial failures). That would have been an entire career for most people but for Altman it’s barely a fifth of his output.

I also note that Altman’s breakthrough work, MASH, was released when he was 45 years old. 45 and he was just beginning! So there’s hope for me yet.

California Split

SPOILER ALERT

American cinema doesn’t get any more behavioral than Robert Altman. This is storytelling of a very high order. Even though the film is tightly plotted, it feels like it has no plot at all. There are very few scenes that even feel like they’re scripted; it feels more improvised. Not only is the dialogue loose, a good deal of it is completely meaningless. Especially Elliott Gould’s character, who, like Shakespeare’s Gratiano, talks and talks all the time and never says anything.

The story, briefly: George Segal is a gambler on a losing streak, and he meets up with Elliott Gould, who doesn’t seem to attach much importance to winning or losing. He doesn’t see an “end game” to gambling, he just likes to gamble. But George, the second act announces, is in debt to a guy named Sparky, and has to come up with some money. George is out of money, but Elliott always seems to have enough to get by, and the two of them go to Reno and, against all odds, win over eighty thousand dollars.

Gambling, it seems to me, is a form of prayer. You put your money down, and you hope that God favors you. If you win, then your faith is rewarded. If you lose, then God is angry with you for some reason.

When you study the statistics, when you study the Racing Form, when you “bet with your head,” you’re saying that you’re not going to place your faith in anything unless you’re sure it’s a sure thing, which is another way of saying that you have no faith at all.

I think maybe that’s why cheating is so reviled, because the cheater has no faith. The cheater believes that one can be redeemed without faith.

So there’s George, and he’s on his cold streak, and he’s down on his luck, and we sympathise. Why? He’s a degenerate and a loser, why do we like him? Because we feel like we’re losers too, we feel like we’ve been shut out of some better life.

And George sells his car and his typewriter and his radio and tape recorder and takes all his money and all of Elliott’s money (which he’s gotten by hustling basketball and mugging a guy in a bathroom) and they head to Reno. And once the stakes are raised, Elliott sees everything as an omen. The snow is an omen, the carpeting is an omen, the decor is an omen. This is faith of a paranoid kind, if the carpeting is a sign that you’re blessed.

And we want George to win, because we want to win too. We place our faith in George, he’s going to win for us. He’s going to be saved, and we’re going to be saved along with him.

Think of this: all through the movie, we watch George and Elliott bet on all manner of things: cards, horses, boxers, roulette, dice. You bet on a horse, the horse doesn’t even know what money is. Cards don’t care what’s printed on them, dice don’t care how they fall. But in the audience, we’re betting on George, for the exact same irrational reason that Elliott bets on anything; he has a feeling. And if George wins, then our faith is rewarded. If he loses, then there is no God. We become complicit in the theme and message of the movie.

And guess what happens: George wins, BUT.

But after he wins, there’s a scene at a bar, just George and Elliott. And George is miserable, and Elliott is very very happy, and they have this exchange:

Elliott: You always take a win this hard?

George: There was no special feeling. I only said there was.

Elliott: I know. It doesn’t matter. We made a lot of money.

So George placed his faith, and his faith was rewarded, but in his moment of vindication, he’s realized that the dice are not God, they’re only objects, their numbers have no meaning. It took this incredible winning streak for him to finally realize that there is no vindication in winning a gamble.

Not to drag Mamet into this, but there’s a scene in his TV movie Lansky where Meyer Lansky (played by Richard Dreyfuss) goes to his gangster friends to get some money to build a hotel in Las Vegas. Gambling has been going on in Vegas for some time, but only marginally, in gas stations and bus stations and such. And Lansky holds up a sign he took off the wall of a gas station, one that was hanging over a one-armed bandit: “Higher pay means longer play.” “Gentlemen,” he says (I’m paraphrasing) “This sign is telling you that we will take all your money. What it promises is that it will take us longer to do it than others.” Mamet’s point is that there is something pleasurable and exciting about gambling itself, even in the act of losing, that people can’t get enough of, that the point of gambling isn’t winning or losing, but rather the thrill of betting itself.

After the bit about the “special feeling,” Elliott says that they have enough money to visit every track in the world, he says they have enough money to live at the track for fifty years. Because for him, there is no end to the game. Life is the game. You don’t quit the game; what else is there?

So George looks like he doesn’t like the sound of that idea, and there’s the following:

Elliott: So what do you want to do now?

George: (pause) I’m going to go home.

Elliott: Oh yeah? Where do you live?

And what he’s saying is, this is where you live, in the casino, at the dice table, at the card table, at the track. And we’re worried that he might be right.

Mr. Urbaniak will note that California Split features a three-second appearance by his Fay Grim co-star Jeff Goldblum.