Live and Let Die

religion, sex, race, drugs and politics in a surreal head-on collision.

WHO IS JAMES BOND? James Bond is, miraculously, young again, or at least seems to be (although Roger Moore, it should be noted, is in fact three years older than Sean Connery). He has hair again, and he carries his world-saving burden lighter than ever. He’s game, no longer smirking or winking, no longer punching women or minorities (rather the opposite here, as we shall see), seems altogether happy to be here. Good for him!

WHAT DOES THE BAD GUY WANT? I am pleased to say that Kananga, the bad guy of Live and Let Die, is, up to this point, as far as Bond Villians go, second only to Auric Goldfinger in terms of his complexity, intelligence and fiendishness. Kananga is both the leader of small Caribbean (republic? dictatorship? I didn’t quite catch it) called San Monique. In addition to being leader of San Monique, he also poses as “Mr. Big,” the head of a positively gigantic, incredibly well-organized black crime syndicate. As Kananga, he is the upstanding leader of a small island nation; as Mr. Big, he is the most powerful black criminal in the US. He plans to use his presidential power as a front to make a move to taking over the totality of American organized crime, by introducing two tons of pure heroin into the American marketplace, for free, causing chaos in the street, certain death to thousands, disaster for the currently reigning Mafia, and eventual dominance for both Mr. Big’s sydicate and Kananga’s island nation (where the poppies are grown). Whew!

WHAT DOES JAMES BOND ACTUALLY DO TO SAVE THE WORLD? British Intelligence is, for some reason, interested in Kananga’s scheme, and their men keep getting killed in the course of their investigations. Bond is called in simply to investigate their deaths. He travels to New York to investigate Kananga, gets kidnapped by Mr. Big, escapes, travels to San Monique, investigates Kananga there, discovers the heroin fields, follows the heroin trail to New Orleans, is kidnapped by Mr. Big again, finds out that Mr. Big is the same guy as Kananga, is fed to alligators, survives that, destroys Mr. Big’s heroin-processing factory, then travels to San Monique to also destroy the heroin fields. Taken prisoner one more time, he turns the tables on Kananga, fights him, blows him up (rather literally, in one of the few ugly moments in the movie).

WOMEN? Three: an Italian intelligence operative in London, a Kananga/CIA double-agent, and fortune-teller Solitaire, about which more later. Apart from pulling a gun on the double agent (understandably under the circumstances) Bond is unfailingly polite, charming and sweet to these women (if not exactly deeply committed).

HELPFUL ANIMALS: It’s another new Felix Leiter, this time an American man more-or-less the same age as Bond, a little more cheerful than the last one, but again over-burdened with babysitting and make-work. Bond runs around saving the world, blowing shit up and screwing beautiful women while Felix sits in a hotel room, answers the phone and takes complaints from people who have had property destroyed by Bond. All I can think is, what the hell is Felix? An operative, a bureau chief, an operations officer, a political appointee? Why is he going around in public introducing himself? Have we learned nothing from Valerie Plame?

Then there’s Rosie Carver, the CIA/Kananga double-agent. Rosie is new at this espionage thing; she screams in terror when she sees a dead snake or a hat on a bed, but for a time she is Bond’s teammate on this adventure. She presents a comic possibility that goes mostly unexplored in this movie and, to my memory, the Bond universe: the mismatched partner. The idea of Bond teamed up with a green, skittish, black female (essentially, an individual who is everything he is not) is a good one that gets too short shrift here.

And Quarrel’s back! Or, rather, “Quarrel Jr.,” since the original Quarrel got killed by Dr. No’s “dragon.” In Dr. No, Quarrel was the bug-eyed native cowed by the scary man’s voodoo; here, he’s a CIA operative (and fishing-boat entepreneur) who sees through Kananga’s voodoo, knowing there are baser motives to his spirituality. A big promotion for Quarrel; sad that it took 11 years and a generation to make it this far.

HOW COOL IS THE BAD GUY? I must say, I find Kananga very cool indeed, especially as played by Yaphet Kotto, who makes him, I will argue, the most complexly-motivated Bond Villain yet, by a wide margin. He is both eerily calm in the enormity of his wealth and power and desperately seething at the thwarting of his gigantic ambitions. In one moment he will be cynically sneer at the predictability of the world, and in the next will tremble at the uncertainty of the spiritual world. For Kananga is more than just a politician posing as a gangster (or the other way around), he’s a deeply religious man posing as a brutal capitalist. He’s not just cynical, he’s schizophrenic; the light/dark schism runs through every fiber of his being (a schism echoed by the makeup of one of his associates, Baron Samedi, pictured above). Kananga’s perfectly willing to enslave thousands of innocents to a life of drug abuse in order to enrich himself and gain power, but he also worries a great deal about the good favor of his fortune-teller-mystic-vestal-virgin-high-priestess Solitaire.

Solitaire, in spite of her ridiculous outfits, garish makeup and standard-issue Bond-girl helplessness, represents a genuine effort to introduce a real, three-dimensional female character into the Bond universe. She’s not just there to be saved and then screwed (or vice versa), she’s got plans and worries of her own, ones that actually tie into the bad-guy’s plot and, further, into more mystical realms. Solitaire, according to her spiritual tradition (whatever that is), will lose her precognitive abilities if she has sex. She does and does, and the sense of genuine loss and sadness that ensues is palpable and affecting. Just as Kananga cannot reasonably expect to be both a crime lord and a spiritualist, Solitaire must also make choices about following her own spiritual path (which involves serving Kananga’s evil plot) or becoming her own woman (which involves, of course, screwing Bond — this isn’t Seven Years in Tibet, folks).

If Kananga’s coolness ended with his rapacious ambition, his schizophrenia and his love/hate relationship with Solitaire, he would still be plenty cool. But it doesn’t! No, he also has whole raftloads of other cool characters surrounding him. First, he has, and this is not an exaggeration, the organized, explicit support of every black person living in Harlem, New Orleans and San Monique. Now that’s a conspiracy! There’s no sneaking around or secret codes or hidden agendas — if a British agent in New Orleans needs to be assassinated, Kananga can just ask a few dozen of his fellow conspirators to stage a mock funeral in the French Quarter, kill the guy in broad daylight, and walk off with the body. If another British agent stumbles up to Harlem, he has literally dozens of operatives tracking his progress through the streets every step of the way. You don’t see this kind of power your garden-variety Italian gangster operations.

In addtion to the support of hundreds of thousands of ordinary citizens, he’s got Tee Hee, a towering fella with a mechanical arm. Played by Julius Harris, Tee Hee manages to be scary, menacing, funny, and the best henchman since Oddjob. (I wish that our cinematic fake-arm technology was what it is now, because Tee Hee could use some of that Pirates of the Caribbean Davy Jones CGI magic.) He’s also got the oddly affecting Whispers, an assassin with what sounds like damaged vocal cords, and the aforementioned Baron Samedi, a voodoo priest (and a mean choreographer of rituals) who has his own unpredictable bag of tricks. Not to mention both an alligator trap and a shark tank! And a monorail! Man! This guy oozes cool!

Minus one point for trying to kill Bond by, again, dropping a poisonous animal into his hotel room. Has anyone ever been killed this way?

NOTES: I must say, this movie took me by surprise. Like any given episode of The Venture Bros, it’s completely ridiculous on its surface, oddly sincere and thought-provoking in its middle, and utterly, deeply weird at bottom. That’s three levels! Try and think of another Bond movie with three levels! You can’t!

Let’s start with the race thing. Putting lily-white Bond in a story filled with black folks (northern urbanites, southerners and island natives) could have been uncomfortable at best and disgustingly racist at worst. And yet Bond navigates this terrain with relative ease. In Diamonds Are Forever, Bond was reactionary and reactive, fending off attacks on his straight-white-British-maleness, but here he’s wise (and generous) enough to realize that he is, in fact, the uncool one, and plays his uncoolness for something actually resembling high comedy. Sure, some ofthe “black language” is dated, but Bond never plays himself as superior to the people he encounters, even when they’re trying to kill him. He’s in over his head, he knows he is, and he adjusts his attitude accordingly.

It might sound racist to suggest that entire black populations of cities would willingly support the murderous scheme of a schizophrenic madman, but Live and Let Die meets the rising black cinema of the day and confronts it head-on. It must have seemed, and not just to whites, that there really was a whole secret black international culture, with its own rules, morality and code of honor. White America certainly wasn’t going to grant blacks power, not without a fight. Why not support a man like Kananga, or a gangster like Mr. Big? Their plans for domination may not be perfect, but at least they address the problem of the dominant white culture.

But Live and Let Die doesn’t stop at examining race problems in America, it goes on to examine religion too. I don’t know enough about voodoo to say how much of the stuff on display here is accurate and how much is total bullshit, and I can’t say I enjoy watching black people go bug-eyed and spooked by voodoo talismans. But the mere fact that a Bond movie, for the first time, incorporates a genuine religious belief into a story at all has to count for something. It’s true that Kananga is using his local voodoo temple as a cynical ploy to dupe the locals, but it’s also true that the mystic holds a great, even crippling, power over both him and his court priestess Solitaire. Baron Samedi, for his part, refuses to stay pigeonholed — every time he is exposed as a fraud, he turns up again with a new, unexplainable miracle.

For instance, at the end of the movie, they do the “but one assassin would not stop” beat, and have Tee Hee show up to menace Bond in a train compartment. And the screenwriter says “Why? His boss is dead, why would he bother?” But then we find that Tee Hee is not working for Kananga, but for Baron Samedi, who has, apparently, magically, survived several assassination attempts and is, even now, riding the locomotive engine, laughing into the onrushing night. With this moment, suddenly the entire preceding narrative is thrown into question, as we realize that Bond may have gotten the wrong man, that all of this is a puppet show put on by a chortling voodoo priest. It’s a creepy, surreal moment that is not easily reconciled.

But wait, there’s more! The 70s car-crash genre was coming on strong, and Bond here steps forward to stake his claim. There’s no mere tilting-a-car stunt here, no: there are three major, impeccably-mounted chase sequences. One is a bus-and-car chase through the jungle, one is the parking-lot chase from Diamonds re-cast as an airplane-and-car chase across an airport tarmac, and one is a stupefying boat-chase-that-will-not die. To top it all, Clifton James shows up as the drawling, mewling, tobacco-spitting redneck sheriff J.W. Pepper. This character, the stubborn, fuming, none-too-bright, impotent southern law-enforcement officer, is one that would be revisited to the point of dead-horse-ness throughout the 70s, but James is so specific in his choices and so vivid in his delivery that J.W. pretty much explodes off the screen and one is sorry to see him go.

All I will say about the title song is that I have a sizable, extensive obsession with the life and career (if not necessarily all the music) of Paul McCartney, which will have to remain a subject for another day.

Roger Moore, I must say, immediately makes an impression as Bond and justly owns the part. If he is not as darkly sexy as Sean Connery was in 1962, he does put his own highly-crafted spin on the part. If he had been playing Bond in Diamonds Are Forever, that movie might have been the light comedy it aspired to. As it is, Moore handles the comedy here quite deftly thank you, and also manages to communicate Bond’s style, resourcefulness, ease and lethalness. His luck with the ladies isn’t as strong; when he approaches, say, Rosie Carver, and suggests they go to bed after mere minutes of acquaintance, he comes off less like a smoothie and more like a creepy masher.

The photography is a big step up from Diamonds, and the use of locations is imaginative. There’s a Ken-Adam-esque airport terminal (real life catching up to Bond Movies), a terrific, crumbling, ash-colored Harlem back-alley, a convincingly run-down island town, and the lush green jungles of San Monique. The special effects are also much better.

There is a scene toward the beginning where M shows up, unexpectedly, at Bond’s house to deliver his assignment. Bond has a bird in his bed and there is some ho-hum comedy wrung from his attempts to keep M from finding the girl. Why, I don’t know, except that M is a father to Bond and one is always embarrassed to reveal to one’s father that one is getting some tail. But then Moneypenny shows up and instantly discovers the girl, and her reaction is both sweet and heartbreaking. She helps the girl hide in a closet, gets her her clothes to preserve her dignity, then trades her usual quips with Bond as though nothing has happened. Her loyalty to Bond trumps her jealousy of seeing the cheap floozy sneaking around the house. Bond is unaware of what Moneypenny has done, and goes on with his boyishly smutty life, while Moneypenny gives him a look and a sigh that tells us that seeing Bond in his element, after years of half-kidding flirtation, has truly crushed her spirit. Bond, she suddenly knows, will never be hers, will never be anyone’s, really, and will never even know, is incapable of comprehending, the depth and extent of her affection for him. It goes by in a mere moment, but it’s a brilliant performance and could be Lois Maxwell’s finest hour.

Diamonds Are Forever

Mr. Wint glowers, Tiffany Case ogles, James Bond calls his agent.

WHO IS JAMES BOND? James Bond is a smug, balding, doughy, middle-aged swinger, missing only the velour shirt and the gold medallion to complete the picture. The only piece of identification he carries is his Playboy Club card. However, it seems he also works for some kind of British spy agency (“British Intelligence,” he burrs, late in the movie, to an American billionaire). By the time the titles begin, he has killed the man he’s been battling with for four movies now, Ernst Blofeld. Bond tracks down Blofeld via a brilliant, time-honored method of detection, punching people in the face. He punches, to be precise, an Asian man, an Egyptian man, and a skinny French woman. Once upon a time, James Bond would seduce a woman in order to get information from her; now he’d just as soon strangle her with her bikini top and then punch her in the face. Once the epitome of cool, Bond has become a smirking, exasperated, reactionary crank, and before this movie is over he will defend his straight-white-male Britishness from simpering gay assassins, Italian gangsters, a Jewish comedian, a bi-racial team of female martial artists, redneck doofus cops, an egghead peacenik and a cross-dressing supervillain. All in a rollicking, “just kidding” tone. In this, he starts to resemble less the Bond of old and more the then-emerging pole-star of aging straight-white-maleness, defending his turf in a changing era, Archie Bunker.

When is this nefarious scheme revealed? I’m glad you asked. An hour and thirty-four minutes into the movie, that’s when.

ABOUT THIS DIAMOND-SMUGGLING RING: Here’s how it seems it’s supposed to work: poor, black South African mine-workers steal diamonds from their mine. They cheerfully hand them over to a dentist, who hands them over to a guy in a helicopter, who hands them over to a little-old-lady schoolteacher, who takes them to Amsterdam and hands them over to comely young Tiffany Case, who hands them over to some guy, who travels to Los Angeles and hands them over to the director of a funeral home and his Jewish comedian friend (it’s a well-known fact that Jewish comedians make the best diamond smugglers), who hands them over to, I guess, this Willard Whyte fella, who could afford to buy them retail. The simpering gay assassins follow this trail every step of the way, killing everyone who comes in contact with the diamonds.

Now then: Bond inserts himself into this ring, killing the “some guy” to whom Tiffany Case hands over the diamonds and taking his place. He hides the diamonds in the dead man’s intestines (digestive humor accounts for at least half the jokes in Diamonds Are Forever) and flies with the body to Los Angeles, posing as the dead man’s brother. In this particular cutthroat diamond-smuggling ring, no one seems to notice or care that their courier is dead and accompanied by a man they’ve never seen before.

WHAT DOES JAMES BOND ACTUALLY DO TO SAVE THE WORLD? Once he has “killed” Blofeld before the titles, Bond is bored and resentful when he is asked to investigate a mere diamond-smuggling ring. Why is he investigating a diamond-smuggling ring? Because it’s important to the South African diamond-mine people of course, who apparently hold considerable influence with British Intelligence. Well, if it’s important to South African diamond-mine owners, it’s important to James Bond — anything to help out some fellow privileged, wealthy , powerful racists.

Anyhow, Bond shrugs his shoulders and gamely investigates the diamond-smuggling ring, which leads him first to Amsterdam and then to exotic, mysterious Los Angeles, and then to gaudy, trashy, depressing Casino-era Las Vegas (honestly, I kept waiting for Bond to run into Nicky Santoro — now that would have been a movie!). It seems that the diamond-smuggling ring leads to the penthouse of Howard Hughes-like billionaire Willard Whyte (although it seems counter-intuitive that a billionaire would need to smuggle diamonds — why not just buy them?), but once Bond gets to Whyte’s penthouse, he is surprised to find that Whyte is not Whyte but is, in fact, Blofeld — that guy he hates! Quel coincidence! Blofeld employs his simpering gay assassins to kill Bond by shooting him strangling him running him over with a car putting him inside some kind of pipe. This brilliant, devious scheme somehow fails and Bond manages to free the kidnapped eccentric billionaire (who, being straight, white and wealthy, obviously can’t be all bad) from his vicious, beautiful, bi-racial, bikini-clad captors, make his way to Blofeld’s oil-rig HQ, and blow shit up before Blofeld can do too much damage.

HELPFUL ANIMALS: I’ve lost track of how many Felix Leiters this is so far, but this one is crankier and less remarkable than ever. High-ranking CIA agent? He doesn’t seem to have the qualifications of a local police detective. He’s disorganized and powerless. There’s a scene where he and his team are staking out Circus Circus, and all I could think is that Casino‘s Ace Rothstein would eat this guy for lunch.

WOMEN: Bond seems to be through with them. The first one he meets he strangles and then punches in the face, another gets tossed out a window and into a swimming pool (and then, for no particular reason, winds up dead in another swimming pool). He has sex only with dizzy nudist gold-digger Tiffany Case, and even then can’t keep from carping at her, calling her a “stupid twit” in a moment of anger. He’s gotten angry with civilian birds before, but the insults seem to be a new, unpleasant wrinkle.

HOW COOL IS THE BAD GUY? Not cool at all! In fact, the narrative demands that he start out uncool, giving him not one but two uncool deaths before the titles even begin. From there, the relatively cool Blofeld of You Only Live Twice is systematically reduced in stature — he is made to imitate a shallow Texas drawl, flee a Las Vegas hotel dressed as a woman, and dangle helplessly from a crane, until he ends his life as an angry, blustering red-faced clown. In fact, one of the primary dubious achievements of Diamonds Are Forever is turning it’s antagonist into what we have come to recognize as a “Bond Villain,” a vain, silly man with no real plan other than “arching” Bond. When Bond finally gets into Willard Whyte’s penthouse and finds Blofeld there, Blofeld is, literally, doing nothing but sitting there waiting for Bond to show up. Think of that — he’s got a satellite to build and launch, he’s got an oil-rig space center off Baja California teeming with what must be a thousand last-minute crises, but tonight he’s got nothing better to do than sit in Willard Whyte’s penthouse waiting for Bond to show up. With his double (oh yeah, there’s a whole pointless, go-nowhere subplot about Blofeld manufacturing doubles of himself). And his cat. And his cat’s double. And what if, by chance, Bond did not show up, I wonder? Would Blofeld have waited there all night? Would he have canceled his satellite launch? Would he have delegated the running of his space center to an underling? “I can’t make it to the world-blowing-up ceremony, Bond hasn’t shown up yet!”

At one point in Act III, Bond asks Blofeld a question about his operation and Blofeld sighs and says “Science was never my strong suit.” This from a man who, two movies ago, figured out a way to design and build a secret aerospace program inside a hollowed-out volcano. What, I wonder, is Blofeld’s strong suit, besides the high-collared tunic he’s been wearing since 1963?

Charles Gray plays Blofeld this time, exposing the meagre all-around cheapness of the production. Gray played helpful animal Henderson in You Only Live Twice (which goes unremarked upon) and would later stake his claim to camp immortality as the no-necked narrator of The Rocky Horror Picture Show, which, frankly, is a better use of his talents.

The second villains, the simpering gay assassins, as you may have guessed, I have very little patience for. I don’t know if it’s just the performance of Bruce Glover, who plays Mr. Wint, the more simpering of the two, or if it’s the haircut of Putter Smith, who plays Mr. Kidd, the more clown-like of the two, but these two get my hackles up. Perhaps I’m overly sensitive to negative portrayals of gays in movies (and their “humorous,” brutal deaths), but these two offend in a way that, say, Rosa Klebb in From Russia With Love does not. Rosa Klebb indicated her homosexuality exactly once (just in case we didn’t “get” it from her haircut and mannish demeanor) and then got on with the business of being a power-mad killer. Mr. Wint and Mr. Kidd remind us in every scene they’re in that they are, in case we forgot, homosexual men. We are plotting to kill a man, says Mr. Wint, and then spritzes himself with cologne (which smells, we are told later by Bond, like “a tart’s hankerchief”*), closing his eyes and swooning with the sensation. We have just blown up a man in a helicopter, says Mr. Kidd, let’s walk off hand in hand. For we are, as you know, homosexuals, and that fact is always uppermost in our minds. Mr. Wint dies when Bond literally shoves a bomb up his ass; Mr. Wint, we see by the look on his face, is conflicted by this experience, because on the one hand he knows he’s about to die, but you know, on the other hand, he greatly enjoys having things jammed up his ass. Because he is a homosexual man, and that’s how they are.

Putter Smith, I have learned without surprise, is not an actor, but a musician someone connected to the production saw onstage in a band and thought would make a perfect Bond Villain. Which he would, if Bond habitually fought hapless clowns, which I’m afraid he will continue to do for a long, long while.

(*It occurs to me now that the cologne might actually be named A Tart’s Hankerchief, and Bond is merely demonstrating his expertise in identifying perfumes, much as he is able to identify fine wines.)

Slightly more cool are Bambi and Thumper, the limber, bi-racial, bikini-clad assassins guarding the kidnapped billionaire. They are ridiculous, of course, but they do bring a cheerfully electric energy to the movie, especially Thumper, who really seems to be happy to be there, and one is sad to see them brought low by the blandly brutalizing Bond.

NOTES: The reader may have deduced by this point that Diamonds are Forever is a comedy. The central twist, where Bond discovers, after an hour of detective work, that the object of his search just happens to be, by utter coincidence, his arch enemy, pretty much defines the comedic (as opposed to dramatic) approach to narrative. It is certainly better appreciated if it is viewed as a comedy. I don’t mind Bond becoming a comedian, but I wish he would be a generous, light-hearted comedian instead of the bored, smirking thug he is here (I am told that the producers briefly considered casting Burt Reynolds as Bond for this movie, and it’s not hard to imagine him playing some of the scenes as written).

There has been a lot of carping in this space about the “Moore Bonds” and how they ruined the franchise. That may be so, but the Moore Bonds, I’m afraid, begin here with Diamonds Are Forever. Everything in Diamonds Are Forever points to taking the piss out of James Bond and his formula, from the silly moon-buggy chase through the desert to the ever-decreasing menace of its antagonists to the rushed, who-cares sloppiness of its climactic battle.

More than the negative portrayal of gays, I’m concerned about the brutalization of women in Diamonds Are Forever. The director, in the DVD commentary, notes how proud he is of the opening-sequence scene where Bond deftly removes a woman’s bikini top and then strangles her with it. It was very important for the film’s success, he explains, to receive a “U” certificate from the British censors, and this is how they did it — by having Bond strangle a woman instead of seducing her. Sex with a woman? We don’t want kids seeing that. Strangling a woman? Punching her in the face? Throwing one out a window? Drowning one two three in a pool? Perfectly acceptable family entertainment.

And, as long as I’m citing petty liberal grievances, I must note that Blofeld’s cat is brutalized again, this time during the title sequence, where it is made to angrily yowl,repeatedly, for no apparent reason.

Mr. Wint and Mr. Kidd, in addition to being repellent stereotypes, are also terrible assassins. They meet the diamond-smuggling dentist out in the desert, intending to kill him, and choose a scorpion they happen to find on the spot to accomplish that task. What kind of assassin is that? Where is the planning? What is Blofeld paying them for? And of course they pick the largest, darkest scorpion known to humankind, when even a schoolchild knows that the big black ones are actually the least deadly ones. Later, as noted above, they try to kill Bond by placing him, unconscious, into a pipe, which is then laid into the ground, at least twelve hours later, by a construction crew who luckily does not notice the tuxedo-clad Scot in their pipe.

Tiffany Case is flabbergasted when she realizes she is working with James Bond. Why? Well, he is, apparently, world-famous, as all truly successful espionage agents are. This is another example of the reflexive, winking comedy that informs the tone of Diamonds Are Forever, and which does a great deal to deflate whatever narrative tension inherent in the drama.

Sean Connery here stops sounding like James Bond and starts sounding like Sean Connery. Which is fine — who doesn’t like Sean Connery’s accent? — but jars when the movie is viewed too close to his other Bond efforts.

The Howard Hughes-ian Willard Whyte is played by country singer Jimmie Dean, who, it pains me to say, does not remotely begin to suggest the daring, peculiar, brilliant, aging, paranoid, OCD-afflicted Howard Hughes. Hughes, I have learned, was a great fan of the Bond movies and generously offered the use of all Las Vegas (which he owned at the time) for Diamonds Are Forever; I wonder if, after seeing the result, he came to regret his decision.

Diamonds Are Forever holds a special place in my memories because it was the first “new” Bond movie I was aware of. I had seen Goldfinger on television, so I knew who Bond was, and I was even aware that it was somehow special that Sean Connery was back playing Bond (his salary, a then-astronomical $1.25 million, plus 10% of the gross, had made outraged headlines). I clearly remember the commercials contantly playing on TV, emphasizing a stunt where Bond tips a car over on its side to drive through a narrow alley. 1971 witnessed the beginnings of the burgeoning car-crash-movie genre, and I remember my older brother being oh so excited by this new Bond movie and its exciting, special car stunt (I was ten and too young to see something as “adult” as Diamonds Are Forever. Ha!). That stunt now goes by in a ho-hum matter of seconds and seems utterly unworthy of note.

In the middle of Act II, Blofeld turns the tables on Bond and orders him out of his penthouse at the point of a revolver. And I thought “wait a minute, Bond can take on a volcano full of bad guys, why is he acquiescing to a guy with a revolver?” But then I realized that, having punched through the stratosphere with You Only Live Twice, there was, in 1971, no place for Bond to go but to comedy. Bond and Blofeld are play-acting now, just kidding, players on a stage who do what’s expected of them for the entertainment of adolescents and their aging fathers. Diamonds Are Forever is the point where Bond Movies turn from being thrillers to being pageants, if not pantos.

The production, I should note, is quite substandard, especially for a Bond movie. The photography is unremarkable, the lighting high-key and punishing (the better to indicate comedy, I suppose), the supporting players obvious and shrill, the special effects hurried and wan. Perhaps this comes from its lower-than-usual budget (most of which got soaked up by Connery’s salary), perhaps it comes from moving production from England to Hollywood, perhaps it comes from choosing crass, ugly Las Vegas as its prime location. By the time Bond has a car chase up and down Fremont Street (and then up again, because Fremont Street, let’s face it, isn’t that long), outwitting a redneck sheriff and his bumbling cops, he stops being a class act and starts anticipating nothing less than Smokey and the Bandit.

Literary Oddities: Tumbleweed Trouble

As a Hollywood screenwriter, I am exposed to bad storytelling on a daily basis. One tributary of the river of bad storytelling is misguided adaptations of pop-culture icons. “What if Superman were a gypsy farmer?” “What if Mickey Mouse was a molecular physicist?” “What if you re-imagined the Green Lantern Corps as the team from Reservoir Dogs?” (Hey, that one’s not bad — hang on, I need to make a phone call.)

In the sweepstakes of inept pop-culture adaptations, I have, I believe, a winner. This is, I believe, as bad as it gets. This is not fanfic, this is not slash Smurfs, this is not Santa Claus Conquers the Martians. This is The Road Runner: Tumbleweed Trouble by Jack Woolgar (although apparently not this Jack Woolgar.) This is a real book, sanctioned (but apparently not read) by the creators (or at least the owners) of the Road Runner (that is, Warner Bros Inc.) and associated characters, published by a real publisher, Whitman Books (a complete list of other Whitman “Tell-A-Tale” books can be found here).

What makes this book so bad? How does it rise above (or, rather, sink below) the ranks of all other bad pop-culture crap?

Let’s take a look inside, shall we?

brace yourself

very subtle

A brand new comment left on my Tower Records post, from several months ago:

The question from a new user

Hello everybody! I am new to the site toddalcott.livejournal.com

Could anyone, please, advise if there is a lot of

spam and unscrupulous advertising. Can I trust

all this information, which is present at this forum?

Sorry for stupid questions, I just really want know which

information I should trust or even pay attention.

No, spambot. Please do not pay attention. You cannot trust all the information, which is present in this forum. This forum is filled to the brim with unscrupulous advertising.

I get two or three of these a week, but this is, so far, the most, shall we say, "character driven." Gotta love the viral advertising.

Green Eggs and Ham

The inciting incident.

The unnamed protagonist of Dr. Seuss’s illustrated story Green Eggs and Ham wants only to be left alone — to sit in his chair and read his newspaper. He is content, his world is whole and complete. He is comfortable and complacent in his McLuhanesque media circuit. The only thing missing from his life is a name — an identity.

In the past, people like this have brought religion, political change or military turmoil to others. Sam brings green eggs and ham.

(It is, perhaps, significant that the protagonist reads a newspaper — movable type being, after all, the most important, world-shaking innovation in the history of the human pageant.)

Sam has more than an identity — he has mobility and, as we shall see, boundless resources at his disposal. Maybe he’s a shaman, maybe he’s a leader, maybe he’s a snake-oil peddler. Maybe he’s the marketing executive in charge of the Green Eggs and Ham account and this is a viral campaign. We are never told, and we must sort out the dense symbolism ourselves. Is Sam a savior or a demon? Seuss provides no easy answers.

The protagonist knows one thing: he does not like green eggs and ham. This is the same sort of person who knows they do not like democracy, psychoanalysis, astronomy, penicillin, abolition or stem-cell research (or, if you like, political torture, monopoly, pantheism). And yet, Sam will not stop pestering him. If the unnamed (not to be confused with Beckett’s Unnamable) protagonist will not take Sam’s new food straight, perhaps, Sam reasons, he will take it in a more complex form. In short order, Sam offers the protagonist his life-changing meat and eggs in a house, with a mouse, in a box, with a fox, in a car, a train, a boat, with a goat, on and on. And still the man with no identity resists. He spends the entire story trying to avoid change, even as change surrounds and engulfs him. Eyes closed, head haught, he repeatedly waves away Sam and his unusual food. He doesn’t even seem to realize that his life is continuously in danger as he stands on the hood of a moving car, then atop a moving train as it hurtles through a tunnel.

What can change this man’s mind? Nothing less than a cataclysm — car, train, boat, mouse, goat — all must plunge into the ocean. Finally, with death at his chin, the unnamed man relinquishes hiscontrol over his world (it’s a shame George W. Bush was not reading this instead of My Pet Goat on 9/11).

(What drives Sam? A hatred of the status quo? A religious conviction? Do-goodism? Or a simple desire to impose his will upon others? What does it mean that he wants to get the protagonist’s head out of the newspaper, remove his thoughts from the machinations of the world at large, to concentrate on the fleeting, earthly pleasures of the gourmand? Is he Satan? Is he the serpent, offering the protagonist the eggs-and-ham of carnal knowledge? Do the ham and eggs symbolize the penis and testicles? Is this perhaps a homosexual overture?)

Finally the protagonist submits and eats the food. And finds he likes it.

Of course, the story does not end there. In a shocking denoument, the man, still unnamed, typically, goes overboard. He has no greater a sense of himself than he did at the beginning. The man who knew only that he did not like green eggs and ham now knows only that he does. And, just as he was adamant about not eating it before, he is now adamant about eating it now. He crows to the skies regarding his plans to eat green eggs and ham in every possible situation, whether it is called for or not. For example it is not necessary to eat green eggs and ham in a box — in one’s kitchen, in the morning, would seemingly do just fine. Why insist on eating green eggs and ham with a goat? (Seuss draws the line at animals who would probably be interested in eating green eggs and ham, but it’s not hard to imagine that, before long, the unnamed protagonist will be forcing this food on chickens and pigs, unaware of his callous disregard for life.) So while Sam is triumphant in his quest to spread the gospel of green eggs and ham, what Seuss is really getting at is the unchanging simple-mindedness of the masses. “Thank you, thank you, Sam-I-am” intones the protagonist with the attitude of an “amen,” utterly forgetting that, just one madcap romp earlier, he hated this tiny, furry man and his plate of food. The man with no identity still has no identity — he’s just as happy being a green-eggs-and-ham eater as he was being a non-green-eggs-and-ham-eater. This is the knot of the problem Seuss, the master moralist and social critic, presents to us: things may change, but the masses, on a deeper level, do not change. Today it will be green eggs and ham, tomorrow it will be television or hula hoops or iPods, whatever shiny new thing the persuasive new voice brings. The day after it will be Nazism.

UPDATE: It occurs to me that the name “Sam-I-Am” is almost a homonym for “I am that I am,” the name the Old Testament God gave to Moses. Perhaps Sam-I-Am is God and the “Green Eggs and Ham” represent the new covenant with mankind, a different kind of trinity. This would, perhaps, make the unnamed protagonist Saul who became Paul and the train track the Road to Damascus.

Batman: The Movie

Seeking some undemanding entertainment the other night, I put on my DVD of 1966’s Batman.

As bad as it is, it seems silly to attack this movie too strongly. It is, after all, a comedy. More than that, it’s not even a movie. It was not meant to compete with, say, Torn Curtain. It’s merely product, a brand extension, designed to increase the value of a television show.

The plot, such as it is, makes no sense and wanders all over the place. This shouldn’t be a problem for a comedy (Horsefeathers has no plot whatsoever but is still pretty damn funny) but still it tests the patience of an intelligent viewer. The characterizations are loud, silly, grating, contradictory and unfaithful to the source material.

For those unaware of this unique cultural artifact, the plot goes like this: Catwoman, The Joker, The Penguin and The Riddler have conspired to kidnap Commodore Schmidlapp, who, in addition to running a distillery, is the the inventor of a gizmo that can instantly dehydrate people. The bad guys use the device to turn the UN United World Security Council into piles of colored dust. Before they do that, they spend an entire act screwing around with an attempt to kill Batman by kidnapping Bruce Wayne. Catwoman, who is normally a cat-burglar (hence her name), is here turned into a master of disguise, pretending to be a Russian journalist. The Penguin, normally concerned with bird-related crimes, here pilots a penguin-painted submarine and also briefly becomes a master of disguise. The Riddler, being The Riddler, is compelled to give away all their plans with his clues. The Joker is given nothing to do; in retaliation, Cesar Romero has refused to shave his mustache, clearly visible under his clown-white makeup.

The tone veers from genial camp to bizarre, psychedelic comedy. Adam West, looking like the young Harrison Ford (or maybe Dennis Quaid) plays Batman with a keen edge of ironic seriousness. The villains suffer from the same problem as the heroes in Superfriends; they have no characters to play, only a clutch of symptoms. The Batman of Batman: The Movie is not one to brood in a cave between illegal bursts of vigilante activities; this Batman takes place entirely in broad daylight. Batman holds press conferences at police headquarters, trots down the street in crowded lunch-hour traffic and punches a shark while dangling from a ladder. Far from being the world’s greatest detective, this Batman is an easily-fooled dolt who blunders from clue to clue, solving crimes almost by accident.

The climax of the movie, which involves Batman intoning a solemn prayer for peace and the future while holding a garden hose, is almost worth sitting through the rest of the movie.

This evening, my son Sam (5) found the DVD sitting out and asked to watch it. I warned him that it was not the Batman he’s used to, that there would be no swell animation, that this Batman would not be grumpy and sullen, that he walks around in public in broad daylight, that the whole movie was kind of silly, but he was still game.

Enthralled.

I remember when I was a kid taking Batman seriously, but that was a long time ago (I was exactly the same age as Sam is when it first came on TV). Sam has never shown interest in live-action versions of his favorite cartoon stars; the George Reeves Superman got a thumbs-down, and while he’s curious about Superman Returns, he hasn’t pushed to see it.

Tonight he was so caught up in Batman: The Movie that he needed company while watching it. Not to make sense of the plot (which is impossible anyway) but to verify the fact that it was actually happening. He was transported, stunned, horrified, confused (unsurprisingly), intrigued, and held in the grip of suffocating suspense.

While the tone of blithe camp escaped him (the dehydrated pirates were a source of genuine anxiety), he got the broader jokes, such as when Batman can’t get rid of a large, round bomb on a crowded pier and pines "Some days you just can’t get rid of a bomb!" or the Bat-copter crashing, fortuitously, atop a mountain of foam rubber. He asked if there were more Batman movies like this one. I said "Sam, there are, literally, dozens of Batman movies like this one," which delivered to his cerebral cortex a vision of heaven. (Why are those episodes not available on DVD? I assume a rights issue, as the characters are owned by WB and the series was produced by Fox.)

Sam disagrees with my assertion that the Joker does nothing ("No! He zaps those guys with the dehydrating gun!") but he does not approve of Cesar Romero at all. He totally bought the obviously-rubber exploding shark, and its cousin the non-exploding exploding octopus. He liked the penguin submarine and all the bat-machines. When asked what his favorite things in the movie were, he correctly answered "Catwoman and the Batmobile."

Clayface vs. Grey Ghost

Clayface vs. Grey Ghost. Clayface is pictured on the right.

After many months of watching Justice League, Sam (5) abruptly asked to watch “some Batman” today. I got out our old DVD sets of Batman: The Animated Series and asked him which episode he’d like to see. Sam decided the way he usually does, by looking at the pictures on the DVD box, and chose “the one with Clayface.” That would be “Feat of Clay,” the two-part episode introducing the new villain.

I think what he was expecting after a not having seen the show since he was 3 years old was a plot where Clayface wants to do something bad and Batman has to stop him. Instead, this is what he got:

Lucius Fox, an employee of Wayne Enterprises, goes to meet Bruce Wayne in the middle of the night in an abandoned tramway station. Lucius, it seems, has some information on a crooked industrialist named Daggett that he’s turning over to Bruce so that Bruce can give it to the district attorney (which would be Harvey Dent, but that’s another story). Bruce Wayne, however, turns out not to be Bruce Wayne but rather an actor impersonating Bruce Wayne, on the behalf of some gangsters working for this Daggett fellow, who want Lucius dead. This actor turns out to be a Lon-Chaney-style “Man of 1000 Faces” named Matt Hagen. Hagen was in an accident years earlier and sold his soul to this Daggett creep in exchange for a miraculous makeup compound that gives Hagen the ability to fix his scarred face enough to keep working in movies. Trouble is, the makeup is addictive and makes your skin fall apart if you stop using it (a plot that WB would use again, to little effect, in their movie Catwoman, which might as well not have been based on a comic book at all for all it resembled the DC character). Meanwhile, Daggett has gotten tired of Hagen’s unpredictability and puts a hit on him. Daggett’s hit men could easily shoot Hagen, but they decide at the last minute to, instead, dump a beaker full of this magic makeup gunk on his face. The gunk soaks into his skin and affects him on a cellular level, turning Hagen into the hideous Clayface, a monster with the ability to mold his features into any form.

And that’s just Part One.

Setting aside thedarkness of tone and the ugly, brutal quality of the violence, Sam was utterly baffled as to what was going on. As well he might be. He kept turning to me and saying “What’s going on? Where’s Clayface?” (Clayface, indeed, does not even put in an appearance until well into Part Two.) Once Clayface appeared and Batman started pursuing him, he was still confused. “Wait, why is Batman after Clayface? What did Clayface do to Batman?” (Imagine: he’s five years old, yet he already grasps the notion of “probable cause.” A costumed vigilante can’t just pursue a shape-shifting monster merely on a hunch, there are rules!) I tried to explain as simply as I could what was going on, how Batman (that is, Bruce Wayne) isn’t after Clayface per se, he’s after whoever tried to kill Lucius Fox, and that leads him to Hagen (but not before a couple of dead-ends and having to spend the night in jail), and Hagen, after a great deal of angst, embraces his new-found powers as Clayface and uses them, not to commit crimes, but to get even with Daggett, the corrupt industrialist who made him this way. So Batman, by the end of the show, isn’t even fighting Clayface, but trying to help him reintegrate his fractured personality, an issue close to the heart of the 1992 Batman.

It’s impressive how much these early episodes of Batman TAS were real detective shows; there are gangsters and murderers and briefcases full of incriminating evidence and surprising amount of innuendo, references to things unsaid and shady, mysterious moral zones. Characters sometimes have complex, perverse or contridictory motives; you have to really pay attention to follow the plot, even as an adult. Also impressive, after watching so much Justice League, is how dark and painterly the animation is (that is to say, it looks like the Fleischer Superman shorts). Justice League looks like a kids’ show in comparison.

But the darkness and complexity of the plot was a little too much for my little guy to soak in and he needed a pallette-cleanser. He chose “Beware the Grey Ghost,” an episode where Batman teams up with the actor who used to play Bruce Wayne’s favorite costumed crime-fighter, the Grey Ghost, to solve a series of mysterious Grey-Ghost-inspired bombings taking place in Gotham.

This, especially after the scary, sophisticated Clayface two-parter, was right up Sam’s alley. Bruce Wayne watched superhero shows with his dad when he was a kid! Sam was right there. He completely understood who the Grey Ghost was and what he meant to Batman, and it was revealed that Batman has a secret cache of Grey Ghost toys and action figures, you could see the Batman universe snap into sharp focus for him. And when Batman teams up with his childhood hero in order to solve a crime, it was wish-fulfillment on a meta-level.

For Sam’s 45-year-old dad, there was great humor in the episode as well, since Adam West voiced the part of the Grey Ghost and the mad bomber turned out to be a demented toy-collecting manchild played, both in looks and voice, by series producer Bruce W. Timm.

For a bedtime story, it was the new issue of Justice League Unlimited, where B’wana Beast saves the day by punching a giant bee. That was one he could easily wrap his mind around.

For my readers who wonder if I’m ever going to write about a movie made for grownups again, go see the hugely entertaining, compulsively watchable Notes on a Scandal. It features a deft, accomplished script by Patrick Marber, a thunderous, tumultuous score by Philip Glass and a couple of stunning, detailed, utterly lived-in performances from Judi Dench and Cate Blanchett.

The Departed casting notes

The Departed, on top of being riveting entertainment and superlative filmmaking, offers an excellent opportunity to look at the casting process and how the right actors can really help to get across the ideas of the movie. Each actor brings a wealth of associations with them to help raise the tension of the narrative and the expectations of the audience.

MATT DAMON, we know, was already a genius Boston guy in Good Will Hunting, so we not only buy his accent, but we know he’s really smart. Plus, he played both Jason Bourne and Tom Ripley so we know he’s good at lying to people and can kill with a cold heart.

LEONARDO DiCAPRIO we know was in Catch Me if You Can so we know he’s good at fooling people, and he was in Gangs of New York so we know he can take care of himself in gangland, and he was in Titanic so we know that he’s operating under a terrible burden of guilt and shame. Kidding. Sort of. But you know, ever since then he’s kept scrunching up his brow and looking really pissed off, never more so than here, where regret and anxiety waft off of him in waves.

JACK NICHOLSON is more sui generis. He carries so much baggage with him that he presents a case all by himself. No one comes within striking distance of Nicholson’s work in Hollywood today, especially since Brando died. He shows up and you pay attention. From Jake Gittes to Randall McMurphy to Jack Torrance to The Joker, he’s a steamroller of associations and innuendo.

MARK WAHLBERG we know is tough from The Perfect Storm and Three Kings, but we know he’s vulnerable too from those same roles. So we know he can hold his own against the stars in the short run, but we don’t know if he can go the distance.

MARTIN SHEEN we know is tough because he killed Marlon Brando, but he was also President Bartlett so we know he’s wise and fair. (This part, I’ve heard, was originally supposed to go to DeNiro, which would have lent a lot more surprise and tension to those scenes. Martin Sheen killed Marlon Brando, but he kvetched a lot about it beforehand and he struck him from behind when it came down to it. DeNiro would take your head off like swatting a fly and not even stick around long enough to watch your corpse drop to the ground.)

RAY WINSTONE we saw stand up to Ben Kingsley in Sexy Beast, so we know he’s tough (they put a scar on his face for extra toughness), but we also saw that he ultimately lost that battle to Sir Ben so we know things can’t end well for him.

VERA FARMIGA we’ve never seen before so we don’t know what the hell she’s gonna do.

ANTHONY ANDERSON we know was in Kangaroo Jack so we know that he’s capable of doing anything.

ALEC BALDWIN we saw chew out Al Pacino in Glengarry Glen Ross and pull the rug out from under Leonardo in The Aviator. We saw him bomb Tokyo in Pearl Harbor, bomb Vietnam in Path to War and boss imaginary trains around in Thomas and the Magic Railroad. He boned Kim Basinger in The Getaway and Teri Hatcher in Heaven’s Prisoners. Alec’s no chump, he can take care of himself. Unless the bear from The Edge comes around, then he’s screwed.

KEVIN CORRIGAN plays fuckups and losers. I mean that as a compliment.

“She Loves You:” a closer look

Above: the young McCartney, pale and drawn, haunted by his recent encounter, and the ensuing recording. Is the awkward pose a kind of code? And why are the other Beatles obviously distancing themselves from McCartney? Are they worried about possible sniper fire?

Below: the young woman in question.

______________________________________________________________

Your ex-girlfriend has a message for you. The message is, “She loves you.”

And you know that can’t be bad.

Can’t it?

Let us consider.

It is 1963. You are, presumably, a teenage boy, although the song does not specify age or sex. The point is, you have an ex-girlfriend and she says she loves you.

The question becomes: Who is your ex-girlfriend?

Your ex-girlfriend is, apparently, a person of considerable power and influence. How do we know this? We know this because Paul McCartney is her messenger boy.

McCartney, one of the most celebrated young men in the United Kingdom at this point, has recently been in contact with your ex-girlfriend and she has impressed upon him the overwhelming, urgent nature of her message, which is that she loves you. Not only is McCartney impressed, but he is sufficiently terrified of the repercussions of his failure to deliver this message that he has enlisted the aid of his band The Beatles, overwhelmingly the most popular and influential musical act in the UK, to assist him with this message delivery. McCartney, you see, apparently does not know you personally, nor does he know where to find you. All he knows is that your ex-girlfriend has a message for you and it is his urgent need to deliver this message.

And so McCartney has used every ounce of his compositional talent to craft a bombastic, hysterical football-chant of a song, immediate in its impact and devastating in its catchiness, and has enlisted The Beatles to play it, and on top of that has enlisted the aid of Parlophone records to distribute the recording to every record store in the nation, and Swan records in the United States (and, when their distribution capabilities prove inadequate, Capitol). Every radio station in the English-speaking world will be pressed into service to play it, and The Beatles will even sing a version in German on the off-chance that the message might reach you in Deutschland as well. On top of that, The Beatles, leaving no stone unturned, will eventually visit every civilized nation in the world (and Indonesia), playing this song in concerts before millions of listeners, and will continue to do so for three years, in a marathon attempt to deliver this message to you.

That’s some ex-girlfriend.

Who is she? How did she come to wield such power and influence? Why didn’t McCartney simply say to her “I’m sorry luv, I’m a rather busy pop star and this, frankly, seems to be a private matter?” What methods did she use to impress upon him the overwhelming importance of her love, so that he would spend the next three years of his life delivering the message, through recordings and live performance, to every possible recipient in the hope of reaching you? Your ex-girlfriend, it seems, has an iron grip on the attention of Mr. McCartney.

I think we have to allow the possibility that your ex-girlfriend is unstable and possibly dangerous.

What suggests this? Let’s examine the primary evidence, the message itself.

“You think you’ve lost your love, well I saw her yesterday, it’s you she’s thinking of, and she told me what to say.”

Seems simple enough. Let’s move on.

“She says you hurt her so, she almost lost her mind.”

Okay, let’s stop right there.

Your ex-girlfriend has instructed Mr. McCartney to write in his message to you that she has “almost lost her mind.” What kind of declaration of love is that? “Please come back to me, I’M NOT CRAZY.” This passage speaks volumes.

Now let’s go back to that first line. “You think you’ve lost your love.” Why were you trying to lose your love? What makes you think you’ve succeeded in losing your love? How intense were your efforts, and how diligent has she been in following you? And consider the subtext of McCartney’s desperation: “You think you’ve lost your love, well I saw her yesterday.” What he’s telling you is “You think you’ve lost your love, well, she she was able to get to me, Paul McCartney, the biggest celebrity in the UK, a man of considerable power and influence. What chance do you think you stand of avoiding her? Give it up, for the love of God, talk to her, PLEASE, TALK TO HER.”

And “I saw her yesterday.” Apparently she can get to him any time she wants. Note how in every performance of this song, and McCartney must’ve racked up thousands by now, he still sings “Well I saw her yesterday.” She is, for years, in near constant contact with one of the most heavily guarded personalities of his time. This ex-girlfriend, obviously, has her ways of getting to people, and does not give up easily.

(“Yesterday.” There’s that word, a word that would haunt McCartney for the rest of his life. He saw your ex-girlfriend yesterday; is it only coincidence that yesterday is the same day that so shattered him, that saw him reduced to “not half the man [he] used to be?” There’s “a shadow hanging over me” — a troubling image we will examine the implications of later.)

“But now she says she knows your not the hurting kind.” This line could be read a number of ways. Either your ex-girlfriend is confident in her abilities to overpower you physically (Why not? She’s got Paul McCartney wrapped around her little finger) or else she’s whistling in the dark. You have disappeared, fled this dangerous, unstable young woman, in fear for your life, and in her desperation she has crafted a fiction about the nature of your personality. “Come back, I know you didn’t mean to hurt me, I understand completely and I love you, and I won’t let Paul McCartney out of my clutches until you respond in kind, in order to prove my point.” What could this possibly be except the actions of a crazy person?

(In German! They recorded a version in German! Why? Has your ex-girlfriend expressed a concern that you perhaps have amnesia, and are living in Germany? Does she think, perhaps, that some German-speaking friends or relatives might relay the message to you? What evidence does she have of this? Does she think that, in your desperate avoidance, you have fled the country, changed your name and taken up speaking a foreign language? What the hell did this young woman do to you?)

“Although it’s up to you, I think it’s only fair.” Yes, that’s right, it’s totally up to you. Please don’t let me, Paul McCartney, biggest pop star in the UK, influence your decision in any way, it’s absolutely your decision to make. HOWEVER: “Pride can hurt you too.” Ah, there’s the rub. It’s utterly your decision to make, but YOU WILL FEEL THE PAIN OF THAT DECISION.”

“Apologize to her.” Oh, now wait, what the hell? I thought the message is that she loves you, now she’s demanding an apology? Not herself, of course, no, that’s not her style. No, it’s McCartney, McCartney is pleading with you, please, for the love of God, apologize to her, or you will find yourself in a world of pain. This is no tender declaration of love, this is a plain-spoken threat.

“And with a love like that, you know you should be glad.” Yes, you should be. But McCartney, at this point, is fooling no one. Look at the way certain phrases are repeated, chantlike, over and over — “She loves you, yeah yeah yeah,” “and you know that can’t be bad,” “and you know you should be glad.” This is what Shakespeare referred to as “protesting too much.”

An image forms in my mind. The Beatles return from a world tour, exhausted and terrified from their international mission of message delivery. A pale, drawn, shaken McCartney returns home to London, thinking he’s fulfilled his duty, but is greeted at his door by your ex-girlfriend.

The rain pours down, wetting the young composer’s hair as he stands, crestfallen at the sight of the trembling, enraged young woman. “Did you deliver the message?” She asks. “What was the reply?”

McCartney has no answer. Distractedly, he fumbles with a cigarette. He can’t get a match to strike, not in this sodden English weather. “I didn’t hear back,” he stammers, “I did my best. Please, you have to understand –“

“You didn’t even locate the recipient, did you?” she cuts him off. McCartney goes pale. The cigarette, soaked and lifeless, trembles in his lips. He knows that he will have to go back to the other Beatles and insist that they tour the world once again, enduring constant threat to their lives, in the service of this young woman. It’s going to be another long year.

(Did McCartney, perhaps, actually die in 1966, as was widely rumored? Was it at the hands of your ex-girlfriend?)

More important, perhaps: who are you? What did you do to this young woman, who must be a middle-aged woman by now, if she’s still alive? Are you still alive, or did you pay for your relationship with this young woman with your life? When will it be safe for you to come out of hiding? Are you waiting for another message from McCartney, a song whose chorus goes “It’s all right, she’s dead, you’re in the clear?” What will it take to heal this wound? Can your ex-girlfriend ever be satisfied?

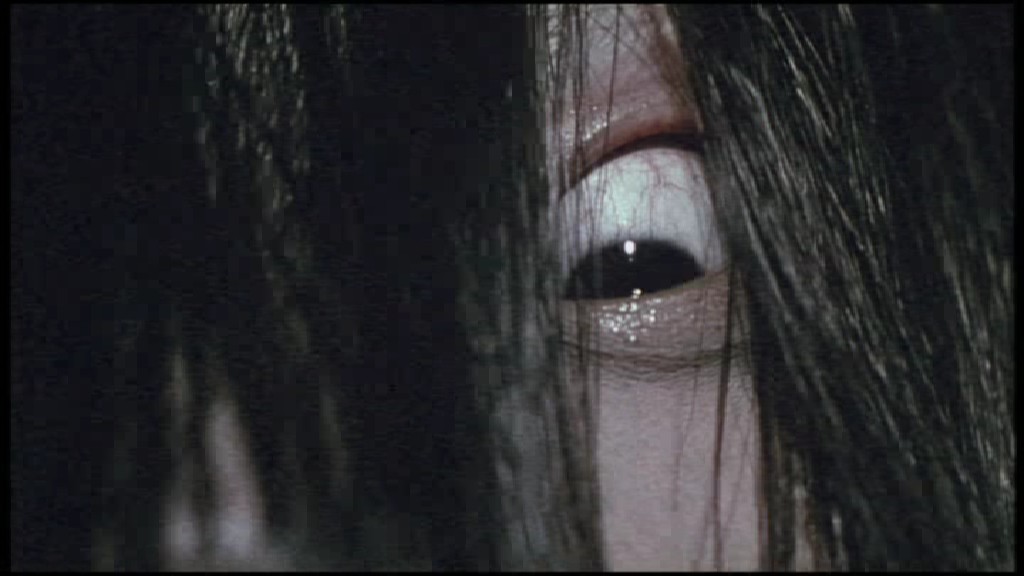

Let’s face it, in the end there is only one possibility: your ex-girlfriend is a supernatural being of terrible power. Your ex-girlfriend may be, in fact, not your ex-girlfriend at all. The song does not, after all, identify her as an ex-girlfriend, merely that she is female, that you “hurt her so,” and that she loves you. She could be your daughter, your sister or even your mother. You may not even be aware of her existence, but she loves you and her love is powerful, constant and unstoppable. She could, in fact, be a ghost and, like Sadako in Hideo Nakata’s Ringu films, she will never rest until her message has been disseminated to every living person on the planet. Which begs the question: what did you do to her? You “hurt her so.” As per Sadako, did you push her down a well because of her awesome powers of destruction?

Whoever she is and whatever her powers, her mark on McCartney was permanent and irreversible. In three short years, she turned him and the other Beatles from cheeky, entertaining moptops to sallow bickering, paranoid drug addicts. What else explains the Beatles’ withdrawl from public life, their investigations into psychedelia and escape into hallucinations, John Lennon’s relationship with the Sadako-like Yoko Ono, George Harrison’s obsession with spiritual life?

What will free the world from the curse of her “love?”

Screenwriting 101 — The Bad Guy Plot

I’ve worked on a fair number of superhero/fantasy/espionage/sci-fi/what-have-you projects, and the problem is always The Bad Guy Plot. For some reason it’s always the toughest thing in the script to work out.

To work, to be satisfying, to move with grace and wit and a sufficient amount of danger and threat, The Bad Guy Plot must do ALL the following things:

1. The Bad Guy’s story should be explicitly intertwined with that of the protagonist. Ideally, the inciting incident should influence both. The perfect example would be if, say, the chemical explosion that gives a man superpowers also gives The Bad Guy superpowers but also a severe deformity, making it so that he cannot lead a normal life and thus turns Bad.

2. The Bad Guy’s desire cannot be simply the destruction of the protagonist. The Bad Guy has to have some other goal that has nothing to do with the protagonist (except in the broadest societal sense, ie the hero’s obligation to right wrongs) but which the protagonist must stop. Like, say, most of the James Bond films.

3. The Bad Guy and the protagonist must interact often and throughout the narrative. This is a whole lot harder than it sounds. If the Bad Guy is involved in something Bad and it’s the protagonist’s job to stop him, what usually happens is that the Bad Guy does the Bad Thing in private while the protagonist looks for the Bad Guy, and then there’s a confrontation in Act III.

4. Hardest of all, the Bad Guy’s plan must make sense and follow a logical progression, not only through the narrative but beyond. That is to say, the writer must stop and think "Okay, let’s say Lex Luthor succeeds in growing his new continent and drowning half the world’s population: then what?" This is what I call the "Monday Morning" question. In Mission:Impossible 2, terrorists plan to take over a pharmaceutical company, release a plague, then sell the world the cure. And I’m sitting in the theater thinking "And on Monday Morning, when the pharmaceutical company’s stockholders find out that 51 percent of the corporation is now owned by a terrorist organization, thenwhat?" When Dr. Octopus succeeds in building a working model of his fusion whatsit on the abandoned pier in the East River, after robbing a bank, wrecking a train destroying a number of buildings and endangering the lives of thousands of people, then what?

Keeping all of this in mind, what are your favorite Bad Guy Plots? Which ones have a plot that intertwines with the protagonist’s plot, has a goal that the protagonist, and only the protagonist, can stop, keeps the Bad Guy and the protagonist interacting throughout, and — gasp — makes sense?

I’ll start: Superman II.