Further thoughts on Return of the Jedi

In the past, I’ve discussed Return of the Jedi and compared its plot to the plot of The Empire Strikes Back. I thought I was done with it, but it turns out the movie has more to offer than I have previously noticed, probably because I in the past I have spent too much of the running time looking at the seams on the backs of the Ewok costumes.

The other day, my son Sam (6) requested to watch it again and kept marveling at how swiftly it moved. No sooner had the good guys escaped from Tatooine than Sam exclaimed “Wow! The movie’s already at the ending!” What he was picking up on was the trifurcated nature of ROTJ‘s plot: it’s a 40-minute movie about the rescue of Han Solo, then its a 40-minute movie about the good guys’ adventures with the Ewoks, then it’s a 40-minute movie about the two-pronged attack on the forces of the Empire. Each one of these featurettes is tight, entertaining and beautiful to behold and no, I’d have to say that, taken as a whole, ROTJ is not a chore to sit through.

Sample conversation:

EMPEROR: The rebels have landed on the moon of Endor, exactly as I have planned.

VADER: Yes, your majesty. My son is with them.

EMPEROR: He is? How do you know?

VADER: I have felt his presence.

EMPEROR: Really? I haven’t.

VADER: If you want, I’ll go fetch him and bring him here.

EMPEROR: Yes, that’s a good idea. Exactly as I have planned.

The Emperor has only one goal: lure Luke to the Death Star so that he can turn him to the dark side. This is, in fact, the only reason he has for building the second Death Star. Because, let’s face it, “Second Death Star” is the lamest idea imaginable. The first massive, impregnable Death Star got blown up by a rebel hotshot, what star-system is going to tremble at the thought of a second Death Star, one that’s still under construction? So the Emperor isn’t planning to use the second Death Star to blow up any planets, he’s using it solely as a big shiny object to lure Luke into his trap. I can see the meeting now:

EMPEROR: I need to get that Luke Skywalker guy here so I can turn him to the dark side.

VADER: Dancing girls?

EMPEROR: No, he’s too much of a straight arrow.

VADER: Double coupons?

EMPEROR: He’s a Jedi, he gets discounts all over the place.

VADER: Second Death Star.

EMPEROR: Second Death Star, that’s absurd, it would be a monumental waste of resources and manpower. The last Death Star made me an utter joke throughout the galaxy. Why on earth would I want to build a Second Death Star?

VADER: I’m just saying, if you want to attract Luke, the ol’ Death Star trick is the best bet going. In fact, I’ll tell you what — let’s only build it half-way! It’ll save us money, it’ll bring Luke here on the run and he’ll be really overconfident!

EMPEROR: Yes. Yes. This is exactly as I have planned.

VADER: (throws up hands in gesture of helplessness)

Princess Leia starts off this movie strong, disguising herself as a bounty hunter to free Han Solo, then strangling a gangster slug to death with a chain while dressed in a smashing outfit. But then what happens? She tags along on a mission with Solo, gets picked up by the Ewoks, finds out she’s Luke’s sister. The end.

Han Solo’s destiny is the reverse of this. His motivation through Act I is “to do something about being blind and getting fed to a monster,” which, in screenwriting terms, is what we call a weak motivation. As Act II begins, he volunteers (as a rebel general, no less) to lead a commando raid on the Endor moon to blow up the Shield Generator. His daring raid gets hijacked, like the movie, by the Ewoks, and the rest of his arc revolves around dealing with the Ewoks, hanging out with them (he spends all night sitting around listening to C-3PO tell stories, then complains about being pressed for time) gaining their trust and enlisting their aid in his guerilla attack on the Imperial troops.

Which brings me to the Shield Generator. The Shield Generator, with its unprepossessing “back door,” becomes the locus of action in Return of the Jedi. The plot of A New Hope is driven by the construction, implementation and destruction of a moon-sized battle station, but the plot of Return of the Jedi is driven by a pair of sliding doors in the side of a hill somewhere in a forest. We’ve got to get in through those two sliding doors! How will we do it? If only there were a rebel army to help us! The Second Death Star, face it, barely figures at all into the plot of Return of the Jedi. It’s of minimal importance. Know how I know? Because it gets destroyed not by Luke or Leia or Han or the droids or even Chewbacca. No, the destruction of the Second Death Star falls to Lando Calrissian and this guy, a giggling, mouth-breathing alien we’ve never met before.

So the focus of Return of the Jedi is no bullshit Second Death Star; the focus of Return of the Jedi is more personal and, ultimately, more mysterious and, in part, goes back to this Shield Generator.

First, let’s divide the players of Jedi into three teams: there are the Rebels, the Imperials and the Ewoks. The Imperials dominate the galaxy with their impressive (if ultimately useless) technological marvels and employment of white, English guys, the Rebels have put together a rag-tag coalition of various species, technologies and whatnot, and the Ewoks are, literally, still living in the trees and fighting with rocks and sticks. So technologically, the lines are drawn: Upper Class (Imperials), Middle Class (Rebels) and Lower Class (Ewoks). The Middle Class, rebelling against the Upper Class, are forced to resort to employing the Lower Class to win their battle. They do not do so willingly — the Middle Class does not understand the Lower Class and their primitive ways, and would prefer not to associate with them. One wonders what is to become of the Ewoks in the triumphant new world after the victory of the New Republic. Will there be cuddly Ewoks, with their spears and animal skins, showing up in the new Republic Senate? Regardless of their role in defeating the Emperor, what kind of power would they have in a new Republican order, being so backward and primitive? It would be like the Tasaday having an ambassador to the UN.

There is also a strong religious component to Jedi. Again, separating the players into teams, what we find is that the Ewoks represent the Old God (which, ironically, includes C-3PO, a droid) (but not R2-D2, oddly enough), the Rebels represent the True God (that is, The Force) and the Imperials represent the False God (The Emperor). If we look at Jedi through a religious lens, it becomes a story about missionaries colonizing a new land and bringing their “advanced” beliefs to the funny, superstitious primitives. Luke becomes the rebellious Christ, representing the new covenant, throwing the moneychangers out of the temple, again, oddly, with the help of the superstitious primitives.

(Or, on a nationalistic level, we could say that the Empire represents Imperial England [which would explain all the English people], the Rebels represent the melting-pot United States with its crazy-quilt of races and ideas, and the Ewoks represent the Native Americans. Which means that in Episode VII, all the Ewoks will die from Rebel-introduced diseases or be wiped out as the New Republic colonizes their moon to put up strip-malls and liquor stores. A few hundred years down the line, the few surviving Ewoks will be granted casino licenses to assuage Republican guilt.)

No wonder the bulk of the movie takes place in “the forest” (after successfully negotiating an exodus from enslavement in “the desert”). It’s not “a forest,” but “the forest,” that is, the Forest Primeval. That is the Forest the Rebels and Ewoks and Imperials stumble around in while deciding the fate of the galaxy. Who is “right” in the Forest Primeval? Which god, which class, shall triumph? How will society evolve? Will we remain with our primitive superstitions, or turn to a False God with its powers to create False Worlds (that is, the Second Death Star) with is awe-inspiring technology, or will the True God prevail?

The Ewoks irritate not because of their character design or their “cuteness” or their obvious racial characteristics but because, for forty disastrous minutes, they derail the plot of the movie, keeping the protagonist from his goal (“I shouldn’t have come, I’m jeopardizing the mission,” frets Luke, perhaps not realizing how right he is) and thrusting Theme into a position of dominance over Plot.

The Shield Generator, then, becomes a metaphor for the “shields” constructed between classes, religious beliefs and friends. There is a shield between the Rebels and the Ewoks, between Vader and Luke, between Han and Leia, between Vader and Obi-Wan. When Han destroys the Shield Generator (nice that the Shield Generator is an invention of the False God), all those shields vanish, allowing Vader to see the Emperor for who he is, Han to see Leia for who she is, and Vader to hang out with Obi-Wan and Yoda in blue sparkly heaven. This is all very nice and elegant, but as I say, the plotting of the middle act of Jedi is a disaster.

Some other thoughts:

1. I wonder what happened to Jabba’s criminal empire after Leia strangled him and Luke blew up his sail barge. It was enormous and powerful enough to make Jabba a force more powerful than Vader in the eyes of the Emperor (otherwise why would Vader worry so much about offending Boba Fett in The Empire Strikes Back?) (I mean, apart from the fact that he’s in love with him), such a thing is not going to simply dry up and blow away like so much roasted meat in the Dune Sea under harsh Tatooine binary suns. Odds are, an intergalactic gang-war erupted after Jabba’s death with many deaths, shady deals and spectacular shoot-outs. The gangster aspect of the Star Wars universe is under-served.

2. Yoda dies, and disappears. Obi-wan dies, and disappears. Vader dies, and must be lugged onto a stolen shuttle and hauled down to the Endor moon to be cremated (or barbequed — it’s not clear; the Ewoks, after all, do eat human flesh and threaten to eat Luke and Han earlier in the movie). I couldn’t care less, but this inconsistency confuses my son Sam. Why do some enlightened beings disappear at the point of death and other writhe in bloody agony? Qui-Gon does not disappear when killed by Darth Maul, hundreds of Jedi die like dogs in the dirt in Revenge of the Sith and do not disappear. Sam posits that only those who come back as ghosts get to disappear, and yet at the end of Sith it’s revealed that Qui-Gon has come back as a ghost — why didn’t he disappear? Darth Vader not only comes back as a ghost (just in time to witness his own cremation — that must feel weird), he comes back as his 25-year-old self. That seems to me to be enough magic to allow one to disappear at the point of death, but apparently not.

3. Leia tags along on Han’s mission to Endor. She dresses in Rebel Camouflage. Then she’s captured by Ewoks, and emerges in a lovely Forest Ensemble. Where the hell did that come from? Similarly, Luke goes on a speeder chase through the woods and wanders around with Han, yet when it comes time to meet up with dad, he’s got on his Don’t Mess With Me Jedi Black. Where do these clothes come from?

4. Luke asks Leia what she remembers of her mother. Leia gives him a sketchy description of an unhappy but loving woman. Odd, seeing as how Leia’s mother is also Luke’s mother and she died at the moment of their birth. Obviously, Leia, pressed into an uncomfortable position, has decided to make up a bunch of utter bullshit in the hopes that maybe that will make her appear more vulnerable and interesting to Luke. Then she finds out Luke’s really her brother — oops.

5. Luke, who’s supposed to be a Jedi (or near enough), is a terrible negotiator. He constantly tells his enemies his plans and opinions, giving them plenty of information and tools against him. I like Luke as much as the next guy but Qui-Gon would punch him in the mouth for that bullshit, and I’m surprised Obi-wan “Truth From A Certain Point Of View” Kenobi puts up with it too. Of course, then again, Qui-Gon is the Jedi who was too principled tosteal a Hyperdrive Generator from a slave-owning junk dealer, so he’s a lame-o too. Obi-wan, though, there’s a guy who decides not to tell his own apprentice (and future savior of the galaxy) that the most Evil Guy in the Galaxy is his father because it serves his purposes. Now that’s a negotiator.

iTunes Catch of the Day: John Zorn

We’ve seen which songs, for whatever reason, I’ve played the most in the last three years, but what actually takes up the most real estate in the sprawling fairgrounds of my iPod?

The winner, the greediest, most space-hungry artist in my library, hands down, is John Zorn, with over 1400 songs on 110 different albums. Zorn is, in fact, a primary reason why I jumped from the 40GB iPod to the 80GB — to include not just my favorites, but to include every god-damned blast, squeak, skronk and squiggle I own from Mr. John Zorn.

Zorn is a true American original — a distinctive sax player, a flamboyantly avant-garde composer, an incredible bandleader and a master of all he surveys. He’s also made himself a legend in the music wars by creating his own label, releasing hundreds of first-class albums in what would ordinarily be a marketing man’s nightmare and insisting upon absolute control of his career. If that were not enough, he’s also acted as mentor and presenter of a whole host of musical outlaws on his Tzadik label.

I came to Zorn through his 1990 album Naked City, which was handed to me by a mentor of my own who had been trying to get me to listen to folks like Sonny Rollins to no avail. It was a good choice for my mentor, who knew that I needed something immediate and demanding to get me interested in a whole new genre of music. Naked City is more than jazz, it’s an encyclopedic engulfing of a century of American music (with some Europeans thrown in for good measure) chewed up in the fevered New York mind of Zorn, played with the intensity of hardcore punk by a crack band of some of the greatest jazz musicians alive. Naked City hit my brain like the Hindenburg at Lakehurst and remains one of my top ten albums of all time. I worked from Naked City (and the seven or so subsequent albums by the same team) to The Big Gundown, his chopping and splicing of the film music of Ennio Morricone, and Spillane, his sprawling, half-hour musical film noir (which he has since expanded into a full-length CD). From there I investigated his game pieces, where large ensembles participate in structured, spirited improvisations, his jittery, menacing, occasionally terrifying classical pieces, his stunning film soundtracks (he is my number one choice for composer when I make my first feature) and his career-in-themselves Masada albums, 17 or so and counting, where, for the first time to my knowledge, a composer has succeeded in wedding jazz to the Jewish musical tradition.

Movie Night With Urbaniak: Viva Zapata!

Biographical drama is hard. The writer is faced with a number of problems — either the audience knows too much about the protagonist, which means they’re way ahead of the narrative, or else the audience doesn’t know enough about the protagonist, which means the movie has to contain all kinds of tiresome exposition to explain who everyone is and why they’re important to the story.

Bartholomew and the Oobleck

Bartholomew and the Oobleck, for the uninitiated, is about a king who gets bored with the weather and commands his creepy magicians to make something new come down from the sky. As I read the first part of this story to my kids tonight, my son Sam (6) interrupted me to ask “Is that really a good idea?”

Oobleck was published in 1949, a time when it seemed that the kings of the world did indeed seem to be bored with the weather of the world and, aided by creepy magicians like Robert Oppenheimer and Edward Teller, deemed it necessary, for reasons having to do with hubris and pride, to have something new fall from the sky.

The narrative tension of Oobleck is palpable as Bartholomew, the lowly page boy, tries first warn the king against his foolish whim, then waits with nameless dread for the coming apocalypse, then desperately races to warn the kingdom of the king’s disastrous mistake.

It’s hard to read this story without feeling a lot like Bartholomew. We all knew our current king’s folly was a bad idea, everyone tried to tell him so, but kings will be kings and so the creepy magicians (Cheney, Rumsfeld, Rice, Halliburton, the Carlyle group, PNAC, etc etc etc) created an apocalypse for the boy tyrant.

(With plenty of little army men for him to throw around the floor of his throne room while he made exploding noises, but don’t let me mix my metaphors.)

The effects of oobleck, it turns out, can be reversed with a simple act of humility on the part of the king. Our boy king, of course, we have learned is incapable of an act of humility, and even if he were, this particular oobleck is, alas, here to stay. Our boy king’s plan, his stated plan, is to keep the war in Iraq going long enough to become someone else’s problem, and, theoretically, never end at all.

(A canny commentator remarked recently that Bush is not, and never was, interested in being president. What he was interested in was winning the election. We’ve seen, indeed, over and over, that Bush’s main objective has always been to win, no matter what he has to do, what laws he has to break or who he has to kill to do so. We’ve also seen that he does, in fact, have no interest in leading, making decisions or doing anything remotely presidential, like treating other leaders, or anyone really, even his own mindless supporters, with anything like dignity or respect.)

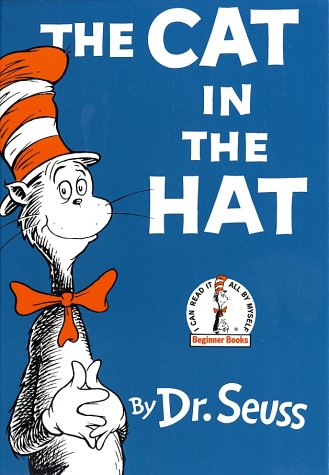

The Cat in the Hat part 2

Preamble: When my son Sam (6) first began to read, I handed him a copy of The Cat in the Hat and asked him to read the cover. He went for the “Beginner Books” logo in the lower center of the cover and read aloud, “I CAN READ IT ALL BY MYSELF.” Then he looked up, amazed, and said “How did they know that?”

Anyway. To review:

The kids (Sally and I) are All Humanity, and they have been abandoned by God (Mom). They sit and stare out the windows of their house (that is, out the eyes of their skull, or the “windows of their perception” [The Doors of Perception, Aldous Huxley, 1954, The Cat in the Hat, 1957]).

The kids, however, are not alone. No, Geisel has given them a companion — a fish. The fish, we will see, functions as their superego. When the Cat encourages the kids to be bad, the fish instructs them to be good. When I first started reading a spiritual metaphor into The Cat in the Hat it seemed flat-footed and obvious that the spiritual superego would be conveyed by a Christ-like fish, but then Geisel is working on a literal level too, and what else would kids have around the house? A gerbil? Would it make sense for a gerbil to pontificate about right and wrong? What’s more, a fish is the natural prey of a Cat (and a black cat is the traditional companion of the witch) (and “gerbil” was probably not on the list of permissible words).

So: kids, house, absent God, Christ-fish. Let’s move forward.

The Cat arrives. Walks in the door, nice as you please.

Why does this not surprise us? Why has no one, of any age, in all humanity, ever in the past 50 years reached this point of the book and said “What? A six-foot-tall talking cat?! With an umbrella?! Fuck this shit!” We buy it. We buy that the Cat is six feet tall, we buy his clown-like outfit of hat and bow tie and gloves, we buy his umbrella.

We buy the Cat because we, like the kids, are waiting for something. That’s why we picked up the book — to be entertained. God is dead and so our lives are meaningless, we live in a state of anxiety, out of balance, waiting for something, anything, to give us some kind of answers about, well, about anything at all.

“I know it is wet and the sun is not sunny. But we can have lots of good fun that is funny.”

The Cat, master con man, magician and trickster (and lame jam-master — honestly, that’s your opening line, dude, is “fun that is funny” the best you can come up with? Is this how you make an impression?) is all too ready to fill this void, the void God’s absence has made. Obviously, the Cat must be the Devil.

Or is he? Maybe, maybe not — it depends on your definition of the Devil.

“‘I know some new tricks,’ said the Cat in the Hat.”

Tricks, not truth. The Cat has nothing meaningful to offer the kids. Not yet, anyway. And he adds subversion and divisiveness to his offer — “Your mother will not mind at all if I do.”

“Then Sally and I did not know what to say. Our mother was out of the house for the day.” The kids are lost, directionless. They cannot stop the Cat from walking in, they don’t know what to make of him, they don’t think twice about a six-foot-tall cat in a clown outfit with an umbrella (the umbrella shows that the Cat can move in a Godless world and not be affected by it — a skill the kids are keenly interested in). Some kids might react strongly at the sight of a six-foot-tall cat in a clown outfit (the hat, gloves and tie are a parody of being “dressed up,” ie “adult”) who can talk, in rhyme, in anapestic tetrameter, but not these kids — they act like it’s the most normal thing in the world.

Why? Why don’t they run screaming? Why don’t they hide? Why don’t they call the police? Because, as I say above, they are living in a world absent God and are looking for something, anything, to fill that void. They don’t run, they don’t scream — check out their faces — they gaze at the Cat with dumb acceptance. They look exactly like children watching television (which is maybe why Geisel did not put a TV in the house — the Cat is “evil entertainment” enough for one story).

The fish, of course, sets them straight, saying, essentially, “HEY! SIX-FOOT TALKING CAT! HEL-LO?“

(The kids don’t react to the talking fish either — why should they? He’s just a fish, a normal, life-sized, unclothed fish. Once you’ve seen a six-foot talking cat, a normal-sized talking fish [one who’s a wet blanket, at that] isn’t going to raise your pulse much.)

The Cat’s first trick is to humiliate the fish, just as the Devil’s first trick is to force you to cast doubt on your faith. Then he goes into his circus act — the ball, the ball, the book, the fish — as the kids look on in mute helplessness. They’re helpless, entranced by the Cat’s shenanigans. They could probably watch him balance a book (the Book?) and a fish (Christ) while balancing on a ball (the Earth) all day long. I know I could.

But the Cat seems to get bored and restless by his own act, and starts adding to it. He adds a boat, a birthday cake, another book and some milk.

The boat seems to signify Christ again, the fisher of men, while the birthday cake perhaps indicates a “new birth” that has taken place, or will soon. The milk is perhaps that of human kindness, but what could the second book be?

In any case, the Cat is not just juggling household crap, he’s juggling signifiers. And doing so masterfully. As one would expect from the Devil.

The act keeps growing — growing, I’m afraid, into the realm of ridiculousness. A rake, a little man, a Japanese fan, a third book, a cup. I could probably find significance in this yard-sale collection of objects, but I think it’s just household crap now. The string is broken — the Cat, not knowing when he’s ahead, has piled too much stuff into his act.

And so he does the only thing he can — he falls. He falls and all the crap falls with him. If it was losing meaning before, it’s lost all meaning now. Now it’s just household crap all over the floor — a mess. The Cat has failed. He’s failed to entertain, he’s failed to provide meaning, he’s failed to replace God.

The fish scolds him and the Cat, instead of eating the fish like a real cat would, picks himself up, dusts himself off and, undaunted, announces a new game.

And here’s where it gets interesting.

The Cat brings in a box, a big red box (I wonder if the big red box is any relation to the “small red box” of David Bowie’s song “Red Money.” Or the small blue box of David Lynch’s Mulholland Dr.) “In this box are two things I will show to you now,” says the Cat. The “two things” turn out to be, of course, literally Two Things: Thing One and Thing Two.

And this is where I must pause. This is very peculiar. What is going on here? Two things? Two things? The work of Dr. Seuss overflows with imaginatively-named creatures, from Cindy-Lou-Who to Dr. Terwilliger to Gertrude McFuzz, why are these creatures Thing One and Thing Two? They’re not Frick and Frack, they’re not Gary and Jerry, they’re not Wizzer and Wuzzer, they’re Thing One and Thing Two. They’re not even described as creatures, only as things. Dr. Seuss has not only refused to give them names, he’s drained them of all possible personality.

Why?

Well, let’s look first at what they do. What do Thing One and Thing Two do? They introduce themselves to the children (who are helpless to resist), then they trash the house in the name of “play.” They fly kites, they knock over a vase, they push over an end-table, they endanger Mother’s dress and teapot and bed (Dr. Seuss, have you met Dr. Freud?). Come to think of it, Thing One and Thing Two don’t hurt the kids and they don’t damage anything that belongs to the kids — only Mom’s things are endangered.

It is only here that the narrator (“I”) puts his foot down. He realizes, finally, what is at stake here and says “I do NOT like the way that they play! If Mother could see this, oh what would she say!”

When I behave in a moral fashion, I occasionally stop and wonder why. A little voice inside me tells me don’t steal that newspaper, don’t throw that wrapper in the gutter, don’t kick that animal. Who does that little voice belong to?

It doesn’t belong to Jesus, and it doesn’t belong to a talking fish. It belongs, inevitably, I think, to my mother. It is our mother’s voice I believe we inevitably hear when we’re tempted to do something immoral. It’s not Dad’s voice, that seems clear. It is, in fact, probably just the opposite for Dad — if Mom is the one who says “Look both ways before crossing the street,” Dad is the one who says “What, you gonna be a pussy your whole life?”

So maybe the missing Mother isn’t God after all. Or if she is a God, she’s a secular, post-war, atomic-age God. A humanist God. God is absent, the humanists say, and therefore we must be moral, for the good of humanity. There is no punishment or reward that awaits us after life in the godless postwar era, only the world we create here on earth through our actions. What are the kids doing? Waiting for Mom to get home. What are Thing One and Thing Two doing? Destroying Mom’s stuff. This bugs the kids (or the boy, anyway — Sally doesn’t seem to have much of a say about anything in this story — Seuss somehow lived through the entire sexual revolution without ever getting around to writing a feminist book).

Okay. Thing One and Thing Two. Let’s take a step aside for a moment and talk about Bruno Bettleheim. In his book The Uses of Enchantment (which I strongly recommend to anyone who wishes to become a storyteller) Bettleheim instructs us that there are always fewer characters in a story than there appear to be. The Wicked Stepmother in “Hansel and Gretel” isn’t really a wicked stepmother, she’s merely the children’s mother when she’s in a bad mood. There is also no “strange woman who lives in the woods” — that too is Hansel and Gretel’s mother, and the story is how Hansel and Gretel feel threatened by their mother and so kill her (which is why she is magically gone at the end of the story when Hansel and Gretel get back from their adventure). In children’s stories, we kill the mother and replace her with a wicked stepmother so that the child can revel in the negative feelings they have about their mother without actually endangering their relationship with her. The proliferation of characters by proxy is a powerful and elementary device in storytelling and Seuss employs it beautifully here.

Why, I ask, Why are they named Thing One and Thing Two? They are named Thing One and Thing Two because they are not real creatures — they are empty signifiers — they are the physical manifestation of the children’s worst selves.

That is the trick, the truth that the Cat in the Hat brings into the house. The Cat allows the children to see their worst selves. The things that Thing One and Thing Two do are exactly what a couple of bored kids would do if they were feeling devilish enough while mother is out. “Good” kids will sit and wait and watch for Mother’s feet coming up the walk (we don’t see Mother’s face, of course — how does one put a picture of God in a children’s book?), “Bad” kids will run around and engage in horseplay and knock stuff over and break things.

Finally, I know why the kids don’t react to the Cat in the Hat. The kids don’t react to the Cat in the Hat because there is no Cat in the Hat. The kids made him up — they created him. They threw the stuff all over the house, they put the boat in the cake, they put the fish in the teapot, they knocked over the lamp. They made up the Cat to take the blame, like children have done since the beginning of time, but then they took it too far — or just far enough, because when the boy is confronted with the physical manifestation of his worst self, he recognizes it for what it is and demands that it leave.

The superego fish says “Here comes your mother now! Do something, fast!” And the boy catches Thing One and Thing Two in a net amid the rubble of his ruined house and orders the Cat to take them away. Now the house is still a mess and there’s no way the kids can clean it up, but the Cat magically returns with a machine of some kind (the deus ex kind, I’m afraid, now that I think of it) and effortlessly cleans it up.

He does all this while Mother is still walking up the walk. Which is, of course, an impossibility. But that’s okay, because in all probability, none of this ever happened. Not content to push the story into the realm of psychology, Seuss now pushes it even further — there was no Cat, there were no Things, there wasn’t even an event — the boy made it all up, a story, to pass the time while waiting for Mother to get home, exactly like the protagonists of Beckett’s late work (Rockaby, Ohio Impromptu, Company, etc.) “It is midnight. The rain is beating on the windows” begins part 2 of Molloy, “It was not midnight. It was not raining” is how it ends.

So there is no Cat, there are no Things, and there is no destruction of the house. What there is is a boyand a girl alone in the house on a rainy day, and the boy tells the girl a story, a story about a giant cat who shows up and wrecks the place, who shows the children their worst selves, so that they may then, with the help of their superego fish, know how to act when their Mother is gone.

Now that the kids have cleared this psychological/spiritual hurdle, Mother does indeed return. The children don’t ask her where she’s been or why she was gone, they only light up like Christmas (sorry) trees upon seeing her.

“Did you have any fun?” asks Mother. “Tell me. What did you do?” To which the boy asks “Should we tell her about it? What SHOULD we do?” Well, indeed, what should he do? The children have taken their first step into a moral life; they’ve fantasized about destroying the house, they lived that fantasy to the fullest, but they have then thought better of it. They now have a secret — some part of them wanted to destroy their Mother’s house. If they tell their Mother, they run the risk of losing her trust (unless they’re Catholic,of course — confession is always forgiven). If they don’t tell her, if they keep their secret, they take a step toward adulthood, a step toward a moral life independent of their mother. Which is, of course, the whole point of good parenting, to get to the point where your children are capable of making their own decisions. Which is, of course, the story of God and humanity — God leaves us alone, refuses to show himself, so that we can learn to make decisions on our own, exercise our free will. In that regard, Mother (God) and Cat (Devil) are part of the same bargain — Mother sends the Cat in as a test of our will, our faith, our sense of duty.

Finally, The Cat in the Hat is not about the Cat, or the hat, or the fish, or the Things, or the mess. It’s about the boy creating a narrative, to entertain himself and his sister (maybe that’s why he has a sister at all, to be an audience). The boy is Seuss, most likely, and he creates a narrative because that’s what storytellers, and all of us, really, do in order to make sense of the world. We make up stories about God and the Devil, or the Cat and the Fish, or Hamlet and Claudius, or Harry and Voldemort, or James Bond and SMERSH, so that we might have a roadmap to guide our life.

The Cat, as cats will, comes back. But that’s a story for another day.

The Cat in the Hat part 1

It’s difficult for us, now, to fully appreciate the impact The Cat in the Hat had on generation of parents, children and educators. The Cat, as an aide to teaching children to read, seems as obvious and omnipresent as the alphabet itself and has not been improved upon in 50 years.

The story of the book, which has been told many times (and can be found in greater detail here), is that the reading programs of the US were a laughingstock for their inefficiency and waste, and an editor of children’s books decided to take it upon himself to rectify the situation. (If someone could find the name of that editor, I would be in your debt.)

Ted Geisel (that is, Seuss) was given an assignment to create a children’s reading primer that would tell a story that uses only 220 easily-recognized words, which were drawn from a list provided by an educational theorist. One might imagine that a book produced by this technique, in kind and understanding hands, would turn out something like PD Eastman’s charming but plotless Go, Dog. Go! But Ted Geisel came up with something more original, daring and explosive.

(Eastman would later climb this mountain beautifully with the woefully underrated Sam and the Firefly, which I hope to get to at another time.)

The story goes that Geisel wrestled with the difficulty of creating his primer for months before taking the first two words from the list, “cat” and “hat,” and saying, essentially, “screw it, I’ll call it The Cat in the Hat,” and going from there.

The Cat in the Hat does its job as a primer very well indeed. It’s lively, funny, and tells a complete story with its bare-bones vocabulary (Seuss would later, of course, trump himself with the 50-word Green Eggs and Ham, which I discuss here). But the thing that makes The Cat in the Hat a classic, what makes it a book that sticks with you, is not that it teaches children to read but that it contains mysterious worlds of allegory and symbolism. It’s open to many different readings and addresses, in its way, some of the most profound questions of human life.

There was a wonderful piece by Louis Menand in the New Yorker a few years ago that gave a modernist interpretation to the story, and which is not available online, (although some criticism of it is — curse you, internet!). The Cat, says Menand, is Seuss himself, who’s been thrust before an audience of children and is required to entertain them with nothing but a handful of arbitrary, meaningless words — cat, hat, wall, cake, run, thing, etc.)

(The Cat carries an umbrella but the word “umbrella” does not appear in the book — not on the list, and difficult to fit into Geisel’s patented meter in any case.)

Having nothing to work with, the Cat throws a bunch of crap together (a ball, a rake, some books) and puts on a piss-poor circus act. One can feel Geisel’s frustration — “I could tell you some wonderful stories, but look what they gave me to work with!” — as the Cat abandons his mission of entertainment and moves on to destroying the house. The Cat becomes a Beckettian protagonist — ‘there is nothing to express, nothing with which to express, nothing from which to express, no power to express, no desire to express, together with the obligation to express” is the way the author of Waiting for Godot put it.

(Beckett, Seuss’s exact contemporary, would dedicate his life to paring down his work to Seussian levels of economy — was this the influence of The Cat in the Hat? Was it the dare of Green Eggs and Ham that took Beckett from the flourishes of his youth to the spareness of his mature work? The opening sentence of More Pricks Than Kicks, an early collection of stories, is “It was morning and Belacqua was stuck in the first canti in the moon.” The first line of his last work, Worstward Ho, is “On. Say on. Be said on. Somehow on. Till nohow on. Said nohow on.” Worstward Ho, like many of Beckett’s late prose pieces, is about the author’s inability to express himself with the tools at his disposal — he would have recognized the cat’s dilemma immediately.)

The Cat, of course, has been denatured, neutered if you will, through time and love and wide acceptance, as all successful comic anarchists are, from WC Fields to the Marx Brothers to Richard Pryor, but the book itself still retains its mysteries and wildness. We see the Cat on a bookbag or bong and smile — he is there to comfort and charm. But, like Charlie Brown (another classic baby-boomer figure), the Cat represents something much darker and more interesting than the merchandising suggests.

“The sun did not shine.” That’s the opening line of this beloved classic. “The sun did not shine.” Not to torture Seuss’s place in the Modernist pantheon too greatly, but I’m reminded that the sun does not shine in a great many of Ingmar Bergman’s movies. In his case, it’s partly because the stories Bergman tells take place during the Swedish winter, when the sun does not shine as a matter of course. But Bergman always used the lack of sunlight (one of the peaks of his art is actually titled Winter Light) to denote a lack of divine light, an absence of God in the lives of his characters. (The Seventh Seal, lest we forget, was released the same year as The Cat in the Hat. There truly was something in the air — maybe fallout from H-bomb tests; that’s what critics thought the characters in Beckett’s Endgame, also published in 1957, were hiding from in their skull-like bunker.)

(When the sun does shine in Beckett’s work, as it does, unremittingly, in Happy Days, it is a harsh, burning, scorching blast without night. Light in Beckett is always important, whether it’s Krapp caught in his Manichean dualism or the protagonist of “Ohio Impromptu” stuck in his unending night or the beings of “Lessness” caught in their gray un-light.)

“The sun did not shine. It was too wet to play. So we sat in the house all that cold, cold wet day.” Well, this is Endgame. Endgame is about exactly this — two people locked in the house on a cold, wet day. All the Cat would need to do is bring in two old people in garbage cans instead of two Things in boxes and they would be the exact same work. The characters in Endgame, like the characters in Waiting for Godot, like the children in The Cat in the Hat, are faced with interminable boredom and nothing but a handful of ordinary props (a stick, a hat, a chair) to entertain themselves. Geisel stands squarely at the crossroads of mid-20th-century angst. Except, of course, he’s an American, which means that his characters’ problem is that they have things, but those things are useless consumer junk, the things we buy with our post-war dollars in order to feel less empty. The kids in The Cat in the Hat sit staring out the window in their house full of junk — a ball, a bicycle (Beckett again, with Molloy’s preferred mode of transport), a badminton racket. In literal terms, the stuff is useless to the kids because it’s all “outdoor” stuff, and it’s raining outdoors. But I am reminded, again, of Beckett, and his sense of indoors and outdoors. For him, the outdoors is everything outside his skull, that is the “real world,” and the indoors is his mind. The Cat kids are stuck not in a house but in their own minds, or in the mind of Geisel anyway.

(That’s why the shelter in Endgame has two windows — the characters are all inside Beckett’s head, and the windows are his eyes out onto the world, which, in Beckett’s view, is a blasted wasteland devoid of life.)

(It’s also worth noting that Beckett’s characters, like the boy and girl in The Cat in the Hat, are pseudocouples. That is, Didi and Gogo, Hamm and Clov, Mercier and Camier, etc, are not really two different characters, but only different aspects of the same mind, a pair of characters who appear to be a couple but who are really only one character arguing with him-or-her self.)

So I’m tempted to bring a both a psychological and spiritual reading to The Cat in the Hat, and will try to do so hand-in-hand here.

The kids stare out the windows of their suburban house the exact same way the characters in Endgame stare out the windows of their shelter, the same way Winnie stares at the landscape in Happy Days (Winnie also has nothing with which to face eternity but a toothbrush, an umbrella (!), some makeup, a hairbrush and a revolver — Seuss, apparently, couldn’t bring himself to include suicide in his list of possible activities for the kids of The Cat in the Hat), the same way The Unnamable stares, unblinking, out of its jar, at the void. They’re looking for life, and meaning, where experience has taught them none exists.

Beckett’s characters search for any signs of life at all — the possible appearance of a flea counts as a major plot point in Endgame — but the kids of The Cat in the Hat are searching for one specific sign of life — their mother.

Because their mother is out on this cold, cold wet day.

It took Time Magazine until 1966 to ask “Is God Dead?” (that’s Time for you, always behind the curve) but the question was very much on the minds of all the big thinkers in the middle decades of the 20th century. For obvious reasons. The end of the world had just narrowly been avoided, only to be threatened by a different end of the world, one that was in the hands of “the good” but which was still infinitely more scary than, say, Nazism.

In any case, the death of God was the central question informing Bergman’s greatest dramas, The Seventh Seal being only the most famous (Beckett’s works support a spiritual reading, but I think in the end his works are all about the act of writing itself — it is only coincidental that they invoke humanity’s relationship to God). But it’s not too far a leap, I think, to suppose that the absent Mother in The Cat in the Hat is God. God has left the children at home and gone off somewhere, she said she’d be back (like Godot) but there is no sign of her. And so all the children can do is wait (like Godot). They have a house full of stuff, certainly there’s a box of toys somewhere (although Seuss declines to put a TV in their house), but all the kids want to do is sit and stare and wait. Clearly, their mother’s absence worries them. Where has she gone, what is she doing, why is she not there? The story doesn’t say, but then God didn’t leave a note either.

The kids will sit and stare and wait (“All we could do was to Sit! Sit! Sit! Sit!” says the narrator [“I,” which I supposed would make “Sally” “Not I”]). Their house full of junk is meaningless and the world outside the house of their perceptions is a blasted void. Nothing has meaning, everything is dark, until their mother returns. Their anxiety about their lives in this suburban purgatory is palpable.

Alas, this is going on longer than I intended and my time grows short and I’m only on page 3. I will pick this up again on the nonce.

The Empire Strikes Back, and I have a question

I wish I could quit you, Lord Vader.

So, Darth Vader is looking for Luke Skywalker. He doesn’t have a chance of finding him (in spite of being able to sense his presence a galaxy away when the plot demands it), but he can, theoretically, find Luke’s friends Han and Leia (and Chewbacca, of course). Han, Leia, Chewbacca (and C-3PO, you know, the robot that Darth Vader built when he was 9 years old) are in Han’s ship the Millenium Falcon. The Millenium Falcon is a fast ship with many tricks up its proverbial sleeves, so it’s very difficult to catch. To catch the Millenium Falcon, Darth Vader can’t rely on his ill-informed, bumbling Imperial forces — he must turn to bounty hunters. "We don’t need that scum," mutters Imperial Guy under his breath when he sees the dregs of the universe cluttering up his Star Destroyer.

So, the official Imperial stance on bounty hunters is: we don’t like you. So it seems that Vader has taken it upon himself to hire the bounty hunters himself, in spite of his officers’ disapproval. Who knows, maybe the bounty he’s offering is out of his own pocket. Point is, Vader has a much different opinion of bounty hunters than the Empire does.

Many bounty hunters apply for the job; only one can catch the wily Han Solo and friends. Scaly reptile in yellow flight-suit Bossk can’t hack it, half-droid-half-insect 4-LOM is a failure, stubby whatsit Zuckuss hasn’t a clue, renegade assassin droid IG-88 couldn’t find his ass with both hands, a map and a flashlight. Only master bounty hunter Boba Fett has what it takes to track down and capture Han Solo in his super-wily Millenium Falcon.

Here’s my question — what’s up with Darth Vader and Boba Fett?

He’s all yours — bounty hunter.

McCartney part 7: John v Paul

The competition between John and Paul is the engine that drove the Beatles to ever-higher feats of compositional glory. It could even be argued that, from Sgt Pepper onward, the Beatles became Paul’s group, that if it were up to the others there wouldn’t have been any more Beatles albums at all after Revolver. And yet they continued to put out masterpieces on a schedule of months (their record company was very unhappy with them for waiting a punishing 18 months between the albums Sgt Pepper and The White Album, with only Magical Mystery Tour, “All You Need Is Love,” “Lady Madonna,” “Hey Jude” and “Revolution” to sell in between — sweet hopping Jesus, what a schedule). The fact that most bands these days can’t be bothered to put out mediocre product on a schedule of decades says a lot for McCartney’s professionalism and ability to inspire.

The competition between Lennon and McCartney’s continued after the Beatles breakup, but took on a much uglier, detrimental turn. It would be nice if these two songwriting titans could bring themselves to compete with the other acts of the day, but the fact was that there were few others who could match their talents. Who is Lennon going to compete with, Bernie Taupin? Is McCartney going to worry about Steve Miller breathing down his neck?

So while it is unhelpful to compare apples and oranges (you know, why didn’t McCartney start an Orange label for his records? That would be just like him), a Beatle fan in the 70s could not help but compare the products of their heroes, and Lennon and McCartney knew it. For the purposes of this piece, I’m going to begin the competition in 1970, even though Lennon started putting out albums before that; the competition ends in 1980 for obvious reasons.

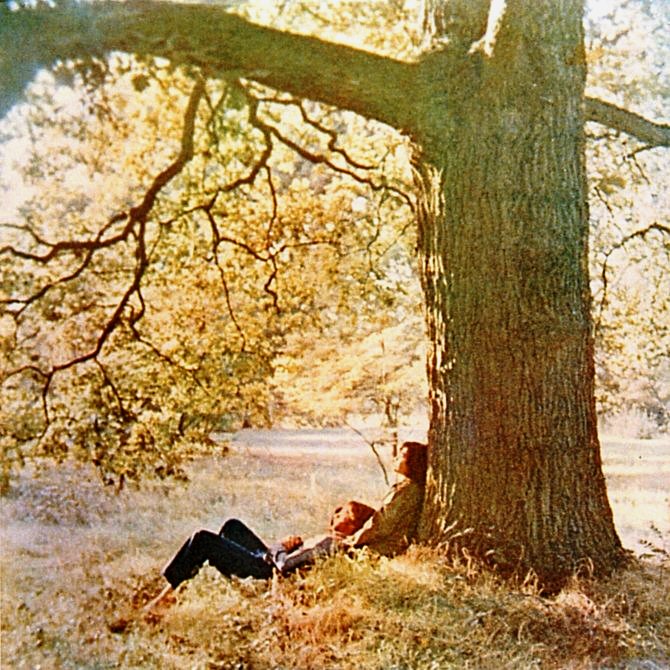

1970: Plastic Ono Band v. McCartney

Directly after the Beatles breakup, both John and Paul decided to remove themselves from the everything-but-the-kitchen-sink, Technicolor polish of the late Beatles style, opting instead for stripped-down, raw, home-made sounds. John recorded Plastic Ono Band, a devastating blast of pain and personal anguish. This was not good-time music, it was punishing, harsh and uncompromising. McCartney, on the other hand, didn’t sound uncompromising, it sounded unfinished, like a collection of demos and out-takes, spare, slender and unassuming. Fans might not have bought Plastic Ono Band, but they could at least respect it for what it was. But they hated McCartney, found it disappointing and limp, a poor offering from the man who engineered Abbey Road. No wonder that neither album was hit, but George’s bloated, over-produced All Things Must Pass was — it sounded like genuine Beatle product.

Plastic Ono Band was a huge influence on me; I’d never heard anything like it before (in 1977, when I bought it). It was more punk than punk and more raw than an open wound. McCartney, on the other hand, seemed irrelevant at best, lazy and unfocused. Nowadays however, I never listen to Plastic Ono Band and McCartney is a consistent delight on my iPod. When I do hear songs from Plastic Ono Band, I keep thinking “Okay, John, okay, I get it,” while the slight, unfinished-sounding songs of McCartney continue to beguile and intrigue.

1971: Imagine v. Ram

In “How Do You Sleep?” Lennon snarls “The only thing you done was ‘Yesterday,’ and since you’re gone your just ‘Another Day.'” These days all I can think of that is “Well, ‘Another Day’ is a fine Paul 1 song, and ‘How Do You Sleep’ is a vicious, unfair slab of character assassination.” Imagine was Lennon coming to his commercial senses, a much friendlier, more polished piece of Beatle product than the “I dare you to like me” Plastic Ono Band, while Ram seemed to be even more irrelevant than McCartney. The anger of Plastic Ono Band was directed outward instead of inward and tempered with a more radio-savvy approach to production. I loved both of these records when I heard them (again, at least six years after they came out), but these days I tire of Lennon’s sloganeering easily and Ram seems better and better as the days go by.

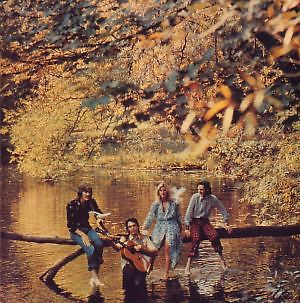

1972: Some Time in New York City v. Wild Life

In 1977 I was obsessed with John Lennon and defended Some Time in New York City to anyone who would listen. Not that there were many 16-year-olds in my acquaintance who had any awareness of Some Time in New York City — I had to special-order it from my local record store, who had never heard of it but professed to liking the packaging when I came to pick up my copy (that same store, which also sold greeting cards, had a policy of ordering two of anything that was special-ordered, reasoning that if one person is interested, another might be, and I took it as a point of pride that I could walk into that store for years afterward and see their second copy of Some Time in New York City still sitting in their bin). Lennon was a hero to me, a man who was using his fame for purposes of good, making daring musical choices standing as a man of the people, defender of justice and champion of peace. Some Time in New York City, of course, then as now, is a terrible, terrible album, an aural nightmare of blare and cacophony, accent on phony, ugly and shrill, hectoring, bombastic, dishonest and nauseating.

It wouldn’t be hard to top Some Time, McCartney could have put out nothing but silence (which is really the only appropriate response) and still come out ahead. Wild Life, however, presents an even more extreme case of redemption. It was an outright commercial disaster when it came out; I put off listening to it for years and hated it when I finally did. I bought it only when I was able to find a copy for less than three dollars, just to complete my collection, and only listened to it once, slack-jawed in horror at its laziness, fuzziness and lack of direction. Then, just the other day I put it on again and couldn’t get over how good it sounded. All those old adjectives still applied, but now they seemed like positive attributes. Wild Life is lazy, fuzzy and lacking in direction, but compared to what became the typical McCartney product of polish, sheen and calculation it positively glistens with life and tunefulness. “Bip Bop,” a song I used to cite as the nadir of McCartney’s composing career, is now charming and delightful, “Dear Friend” is poignant, honest and revealing, and “Tomorrow” is one of his overlooked gems on a level with “Every Night” and “That Would Be Something.”

1973: Mind Games v. Red Rose Speedway

It’s hard to imagine, now, two giant superstars putting out competing albums every year. These days they could not possibly be expected to keep up the pace and not have the material suffer. And while Mind Games is a marked improvement over Some Time in New York City (recordings of weasels being tossed into a wood-chipper would be a marked improvement over Some Time in New York City), Mind Games strikes me as weak and perfunctory. Back in the day I could work up some enthusiasm for it, but even then it seemed like a pale imitation of Imagine. There isn’t anything on it as impressive as “Gimme Some Truth” or “I Don’t Wanna Be a Soldier” or “How Do You Sleep?” and Lennon’s save-the-world-ism even back then sounded naive, silly and ineffective.

On the other hand, back then I found Red Rose Speedway to be a baffling dead-end of misfires and time-wasters. Time, and lowering of expectations, has leavened my opinion of it, but it still strikes me as underwhelming and unfocused (and now I find out that it was supposed to be a double album! sheeesh!). I’m giving Mind Games the edge here.

1974: Walls and Bridges v. Band on the Run

Okay, Band on the Run came out in 1973. Sue me. (Jesus, McCartney put out two albums in 1973, and “Live and Let Die” — what the fuck is wrong with U2, R.E.M., Bruce Springsteen? Who are these poseurs?)

Back in the day, I counted Walls and Bridges “Plastic Ono Band in color,” Lennon’s masterful summation of all his obsessions, produced with care and skill, full of wit and imagination. I still like it okay, but time has not been kind to it. It now feels padded, self-conscious and, again, dishonest. I regularly skip over “Whatever Gets You Thru the Night” and have little patience for “Bless You,” “Scared,” “Old Dirt Road” and “Beef Jerky.” The big production number, “Nobody Loves You When You’re Down and Out,” strikes me as uncomfortably self-pitying and morose, everything Plastic Ono Band was not.

Beatle fans reveled in Band on the Run at the time; Paul’s career suddenly snapped into focus — it seemed like this was finally his Plastic Ono Band. I talked myself into liking Band on the Run at the time; it certainly provided more Beatlesque polish and entertainment value than anything else McCartney had put out up to that point, but it now strikes me as overhyped, overproduced and even ponderous in places. I love the title tune, “Jet,” and “Helen Wheels,” but otherwise the album seems cold, impersonal and hollow, listenable as it is.

1975: Rock n Roll v. Venus and Mars

I loved Rock n Roll back in the day, I found it bracing, fun, invigorating and vital. Venus and Mars I found cutesy, vague, self-important and annoying. What’s changed since then is I’ve heard the originals that Lennon was singing on Rock n Roll and find his production choices to be dreadfully, tragically wrong-headed. I bought the remastered CD when it came out a few years ago and couldn’t finish listening to it — it was loud, sluggish, hugely over-produced and leaden, everything the original versions of those songs were not. Ironically, or perhaps not, McCartney went on to record superior versions of many of the songs from Rock n Roll — whether this is mere coincidence or yet another backhanded attempt on McCartney’s part to degrade Lennon’s reputation is unknown to me.

My opinion of Venus and Mars remains unchanged.

1975-1979: Lennon abstains

Lennon, as is well known, declined to record for the next five years. That would seem like a natural state of being for an artist of Lennon’s stature today, but back then it was an eternity. McCartney ran the field free of competition for those five years, releasing At the Speed of Sound, Wings Over America, London Town and Back to the Egg, all of which were more-or-less commercial smashes, in some cases mysteriously. At the Speed of Sound is godawful — whatever possessed McCartney to actually share album space with the other members of Wings? What the hell was he thinking? Did he really think this band could compete with the Beatles? How is that possible? Or did he just not have enough songs to fill an album and had to get something into the stores to promote on a world tour? In any case, this is the one Wings album I have yet to be able to listen to all the way through. Wings Over America, on the other hand, presents a compelling case for Wings as a musical statement separate from, if not quite equal to, the Beatles. London Town, an album I virulently despised when it came out, has aged surprisingly well — whenever a McCartney tune comes up on iTunes and I think “hey, this isn’t bad, what’s this?” it invariably comes from London Town. Which is not to say that London Town doesn’t contain its share of filler and dreck — “Girlfriend” leaps immediately to mind, as well as non-songs like “Cuff Link.” Back to the Egg, on the other hand, I loved immediately and is still my favorite Wings album by far. It was reviled and unpopular when it came out, which never made sense to me. I loved the weird avant-gardisms, I thought “Getting Closer” and “Spin it On” crushed, and found all the little linked songs spooky and intriguing. My opinion hasn’t changed — every time a Back to the Egg song pops up on iTunes I still feel a charge.

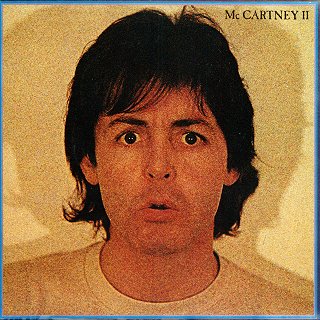

1980: Double Fantasy v. McCartney II

It is, of course, difficult to separate Double Fantasy from the context it appeared in — coming out days before Lennon’s murder, it took on tragic dimensions of shattered dreams and starcrossed love. I, for one, was greatly looking forward to hearing it and bought it on its release date — and was distinctly let down. Lennon’s songs felt weak, thin and slight, and Yoko’s, well, I’m going to go out on a limb here and say that, in my opinion, Yoko’s songwriting talent is not the equal of John’s. There, I said it. I could kind of work up some enthusiasm for the goofy charm of something like “I’m Your Angel” but otherwise itwas an uphill climb. Of course his murder changed all of that.

Time has not been kind to Double Fantasy. Lennon’s songs stand up well for the most part, but no agency on Earth can compel me to listen to any more Yoko Ono. And this coming from someone who enjoys “Cambridge 1969” from Life With the Lions and side 2 of Live Peace in Toronto. Still, seven decent songs on a record is still pretty good, even if some are too sappy and others are too skinny, and I would have very much enjoyed to see where Lennon was going to go from there.

McCartney II has all the sketchiness and home-made-iness of McCartney and absolutely none of its charm or delight. It is a tinny, clangorous horror, even if TLC swiped the opening lines of “Waterfalls.” “Secret Friend” goes on for a stultifying 10 and a half minutes!

Both were big hits.

Give My Regards to Broad Street

Morbid curiosity brought me to watch this movie — slack-jawed astonishment kept me watching.

It’s awful, a train wreck, but not in the way I thought it would be.

It’s utterly wrong-headed, flat-footed and depressing — but again, not in the way I thought it would be.

Paul McCartney (Paul McCartney) is a successful musician and composer with a busy schedule. He’s got a business meeting, a recording session, a complicated film shoot, a band rehearsal and a radio interview, all in one day (given McCartney’s passion for appropriating all of Beatles history, I’m surprised the movie’s not titled A Day in the Life). At his morning business meeting, it is revealed that the master tapes for McCartney’s new album have gone missing. I’ll spare you the details, but the upshot is that if McCartney does not recover the missing tapes by midnight, the record company will be taken over by a big evil corporation. Why this should be so is not explained. Why the poorly-run business affairs of the record company should be McCartney’s concern is also not explained.

So: McCartney has to find his missing tapes before midnight and he’s got an ultra-busy day already planned. What’s he going to do to recover the tapes? If you guessed “nothing,” you’re right! In fact, no one in the cast ever does anything to actually try to recover the missing tapes! The label executives sigh and keen, various roadies and lackeys posit theories and sling accusations, but not one character actually commits a single action toward actually righting the imbalance created by the inciting incident. No one makes a phone call, goes ’round to anyone’s house, checks to see if the courier ever got home the night before. Instead, they just show up every now and then and look balefully at McCartney and worry aloud that the big evil corporation is going to take over the record company. And we, apparently, don’t want that, although it seems to me that any record company who’s going to lose my master tapes and does nothing to try to recover them while I bust my ass running all over town trying to create product for them to sell maybe shouldn’t be my record company any more.

So the tapes are missing and McCartney’s feeling the strain. Feeling the Strain would be a more apt title for this movie. McCartney pads through his day, looking doleful, depressed and tired. In a movie about Paul McCartney, written by Paul McCartney, it’s a big fucking drag to be Paul McCartney — all these goddamn recording sessions and movie shoots and band rehearsals and radio interviews, it’s all just a big tiresome pain in the arse. It’s like a remake of A Hard Day’s Night with the youthful joy sucked out, replaced by a heavy cloud of grownup responsibility. In other words, comedy gold!

So — the tapes are missing and Paul has to get them back by midnight, and no one is helping. You would think that would create some kind of crisis for Paul, or at least some kind of impetus to act. But he does not — he’s got responsibilities! He’s got to, why, he’s got to go to the recording studio, where he’s scheduled to record a medley of “Yesterday,” “Here, There and Everywhere” and 1982’s “Wanderlust!” Who is demanding this medley of two classic Beatle love songs and a middling number from Tug of War? I have no idea, but its recording takes precedence over recovering the precious master tapes, which have been given a stated value of 5 million pounds.

Anyway, the recording session takes a couple of hours, as recording sessions do, and then it’s off to the film studio, where Paul is, apparently, filming a musical, or a couple of videos, or something, it’s not clear. One film shoot seems to revolve around another Tug of War song, “Ballroom Dancing,” staged here as a slightly surreal, British take on West Side Story. Why he should be shooting this is not explained, but it at least makes more sense than the next number, a robotic, 80s version of “Silly Love Songs,” with Paul and the band made up like David Bowie, posing like mannequins while a skinny black dancer does The Robot in the foreground. And you thought you didn’t want to see this movie!

How soulless, uncaring and tired is McCartney? He shows up at the movie studio, goes onto the set for his video, starts shooting, and about a minute into the song we realize that Linda McCartney is on the bandstand, playing keyboard, and he doesn’t even acknowledge her. He doesn’t greet her, kiss her, look her in the eye, smile, or nod in her direction. Nothing would indicate that they’re married. Paul On Business is, apparently, a very cold bastard indeed. And just as you’re thinking “Well, it’s a movie, maybe this is supposed to be some kind of alternate-universe McCartney where Linda isn’t really his wife, but then they show him eating lunch in the commissary, and there she is sitting next to him — and he still doesn’t say a single word to her, although Ringo is, for some reason, given multiple scenes where he chats up Barbara Bach (who, strangely, does not play herself, but instead plays a journalist writing an article about Ringo). 42 minutes into the movie, Tracey Ullman shows up. She’s the girlfriend of the guy who disappeared with the tapes. She doesn’t know where he is and she’s upset. McCartney takes a good deal of time consoling her and talking through her problems while his wife Linda sits six inches away, ignored and without dialogue.

Does Tracey provide a clue as to where the missing tapes are? No, she sure doesn’t! Does McCartney press the point? No, he sure doesn’t! So after he finishes shooting his two videos (it’s about 2pm by now) he slouches off to a joyless, perfunctory band rehearsal in a warehouse across town, even though the band he’s rehearsing with is the exact same band he was just filming with at the movie studio. How they managed this is a mystery. We see McCartney leave the movie studio, get in a beat-up van, be driven across town, be dropped off on an empty loading dock, and go upstairs to a rehearsal hall where all the musicians he just left at the movie studio are already set up and ready to rehearse.

Ah but this is all made worthwhile by the songs right? No. It is not. They suck.

Paul is finding it hard to concentrate on work (I can’t imagine why) and finds his mind wandering. His mind wanders a lot in this movie — he remembers the day when he first hired Harry (that’s the guy who’s gone missing with the tapes), he fantasizes about what his pals the record executives are doing now, he worries about what this corporate takeover might mean to his career. Like I say, it’s a big fucking drag to be Paul McCartney in this movie.

Paul asks a roadie if he’s seen Harry. The answer is no. Sigh. Off to a radio interview.

(I realize I was wrong about Paul not doing anything to recover the missing tapes. He does do something — he worries. I’d like to write a Bond movie that adopts this narrative strategy — Bond is told that Blofeld has a big space-laser pointed at London and it’s going to go off at midnight, but Bond’s got a big day planned of clothes-shopping, bar-hopping, card-playing and casual sex, so he can’t really get to the space-laser thing. So instead we see him shopping for clothes, drinking, playing Baccarat, maybe fiddling with some gadgets at Q Branch, all the while worrying about that space-laser and how it’s going to destroy London in a few hours. And everyone keeps coming around and saying “Boy,it’s a drag how Blofeld’s space-laser is going to blow up London in a few hours,” and Bond’s mind wanders to a day a few years ago when he was having lunch with Blofeld and Blofeld said something about maybe building a giant space-laser — or was he just kidding that day?)

Now it’s evening and we’re well into the third act and Paul has still not reacted to the inciting incident. Instead, as he sings “Eleanor Rigby” in a studio for an audience of stupid, uncaring radio personnel (no one in this movie is the slightest bit impressed with the idea of working with Paul McCartney), he has a very long, bizarre, over-produced Victorian fantasy that dares to invoke both “Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe” and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. This fantasy ends with a vision of his wife and friends dying in a tragic boating accident — all because of those lousy missing tapes.

This baroque, incoherent vision apparently rouses Paul to some kind of action, and he drives out to some kind of pub or hotel or something, where he runs into Ralph Richardson, who lives in a dumpy, overstuffed apartment with a monkey. Aha, you think, here’s the big scene where the truth is revealed — it’s Ralph Richardson with a monkey!

Nope. Nothing. Ralph lectures Paul on spending too much of his time running around, because, you know, you never see the world that way. This from a man who does not seem to have left his room, or his monkey, in years.

Now midnight is approaching and the tapes are no nearer to being gotten. Then, a revelation! Paul remembers singing “Give My Regards to Broad Street” to Harry as he went off with the tapes! Aha! To the Broad Street railways station!

Where he wanders around for about ten minutes. No seriously. He’s not looking for anything, he has no clue or hunch, he just wanders around. As midnight approaches, he sits down on a bench and imagines life as a busker, singing Beatles tunes on a railway platform.

Is this the movie’s message? Is this McCartney’s fear, that if a big evil corporation takes over his record company he will become a homeless busker singing Beatles songs on a railway platform?

Anyway, turns out Harry left the tapes on a bench while he went into a storeroom he thought was a bathroom. Case closed.

So Paul calls his wife (the first time he’s spoken to her in the movie) and she calls the record company, who seem relieved, but not that relieved, and everybody’s happy, and the big evil corporate guys are chagrined. And the viewer goes “Whaaa — ?”

Then it turns out the whole thing was a dream. No really. Turns out there are no missing tapes, no corporate threat, no days crammed full of the joyless drudgery of creating pop hits, nothing. The whole thing was a dream Paul had while passed out in the back of his limo on the way to his office. No really.

I note that this was the first and last feature by director Peter Webb.

Octopussy

WHO IS JAMES BOND? I think the only thing you need to know about James Bond is that he’s the protagonist of a movie called Octopussy.

WHAT DOES THE BAD GUY WANT? General Orlov wants to start a conventional war between the USSR and Eastern Europe. To do this, he intends to set off a nuclear bomb on an American Air Force base in West Germany. He believes the detonation of a nuclear bomb on an American Air Force base will be seen as an accident and will therefore cause, presto! nuclear disarmament. And then the USSR can invade a helpless Eastern Europe. Can’t miss!

General Orlov is played in a Kubrickian fashion by Kubrickian actor Steven Berkoff. Which is fitting, as Orlov recalls no one so much as General Jack D. Ripper from Dr. Strangelove. And that is probably the last time you will ever see anyone use the word “Kubrickian” in a discussion of Octopussy.

Now, it turns out that Orlov is not the “A Villain” in Octopussy. That honor belongs to Kamal Khan, played by Louis Jourdan. I have told you the “B Villain”‘s plot instead of the “A Villain”‘s plot because, frankly, I can’t for the life of me figure out what the “A Villain”‘s plot is. Khan knows Orlov somehow and is connected to him via a smuggling operation (Orlov is smuggling priceless artifacts out of the USSR in order to, I think, finance his nuclear-bomb scheme. But we see in Act III that Orlov’s got both his bomb and his priceless artifacts, so what did he sell to whom and why, and what does it have to do with his bomb plot?)

Anyway, Khan is a fabulously wealthy ex-prince or something who lives in Delhi and helps Orlov smuggle his priceless artifacts out of the USSR. He does this with the assistance of Octopussy, a similarly fabulously wealthy woman who has a private island where she supports an army of beautiful young smugglers who are also circus performers. You can tell how dedicated they are to their work because they wear their circus costumes every day. Octopussy, as one might imagine, has an extremely high self image, as one must in order to carry around a name like “Octopussy.” Especially when one learns that she got this nickname from, gulp, her father. Octopussy is played by Maud Adams, who looks great since being shot dead in The Man With the Golden Gun.

Um, so Octopussy is a smuggler who runs a gigantic, hugely profitable smuggling operation out of her circus. Because you know, if you’re smuggling priceless artifacts, the last thing you want to do is attract attention to yourself, and people generally flee in terror from a circus. (The plot begins with a circus clown being beaten and stabbed to death in the midst of a German forest, and all I could think is “Man, I’ve dreamed this a thousand times.”)

WHAT DOES JAMES BOND ACTUALLY DO TO SAVE THE WORLD? The nicest thing I think I can say about Octopussy is that it evokes fond memories of Moonraker. In fact, I’ll go so far as to say that Moonraker is freaking North by Northwest compared to Octopussy. I can’t say I really blame the screenwriters — who would bring their “a-game” to a movie called Octopussy?

For the third or fourth time, Bond is hired to check into a smuggling ring. Why? Because the clown we see murdered in the opening is a 00 agent, and is found clutching a stolen Faberge egg. It is discovered that a number of stolen Russian artifacts have been showing up at auction houses and this is somehow the business of the British Secret Service.

Now then: the 00 clown is found dead in Germany, murdered by a pair of circus performers, so it’s reasonable to suspect that the 00 agent was undercover in a circus (as opposed to just happening to be dressed as a clown), and I can’t imagine that there were any other circuses in town besides Octopussy’s, and one doesn’t readily forget a circus named Octopussy’s Circus, and yet it takes James Bond, World’s Greatest Detective, over an hour to trace the bad-guy scheme to Octopussy and longer still to realize that she has a circus that is somehow central to this plot.

No, first he goes to an auction for this stolen Faberge egg, where he meets this Khan fellow, who’s buying the stolen egg, then follows this Khan fellow to Delhi, then falls into Khan’s clutches. Only then can he escape Khan, make the connection from Khan to Octopussy, from Octopussy to Octopussy’s circus, and from Octopussy’s circus to General Orlov and his nuclear bomb plot. Phew!

But then we’re not done! No, after defusing the bomb and saving the world, Bond must then go after Khan, because, um, because —

— well —

because —

— because otherwise he might get away with — um —

— well, like I say, I never figured out what Khan was getting out of all this. He’s not helping Orlov for money, he’s not helping Orlov for political gain, he’s not helping Orlov in order to spend time with Octopussy, he’s, he’s —

— well anyway. Screenwriters take note: One villain with one goal is ideal. One villain with two goals is weaker. Two villains with one goal is okay, but two villains with two goals is weak. Two villians, one with a goal and one without, weakest of all.

WOMEN? Roger Moore is okay in my book until he starts putting the moves on the ladies; then he just screams skeeviness. In Octopussy there is a stick-insect femme fatale and Octopussy herself. Neither seduction is remotely believable.

HOW COOL IS THE BAD GUY? Remember how Goldfinger took time out from his evil scheme to destroy the world in order to hustle some gin rummy in Miami? This is even less cool than that: Khan takes time out from his ill-defined scheme to do whatever the fuck he’s doing in order to hustle backgammon in Delhi. Backgammon! A backgammon hustler! What’s next, shuffleboard? And don’t get me started on the tiger hunt.

He also makes a common Bond-villain choice, one that makes no sense to me. Once he knows Bond is onto him, he hires two competing teams of assassins to kill him. Now, I’m no supervillain, but it seems to me you hire one team of assassins to kill a guy, and if they fail you might have a second team standing by, but why would you send both teams out at the same time?

For that matter, how many different people would a guy have to kill in a week that he has two separate teams of assassins on his payroll?

Khan also wears the classic “Dr. No” Nehru jacket, but let’s face it, Khan is no No.

FAVORITE MOMENT: Bond stumbles out of the woods, looking for a ride to the circus. A bunch of kids in a sports car come by and slow down, waving for him to get into the car. As he approaches, they laugh and speed off. The image of the aging James Bond being literally left behind by a bunch of laughing teenagers is heartbreaking and the truest moment in the movie.

NOTES: To say the least, a major step backwards for James Bond after For Your Eyes Only. It suffers from a nonsensical plot, an interminable Act II, and a motiveless villain. It contains both a fight scene ended by a fortuitous crocodile and a thug with a circular-saw yo-yo. The last half-hour of the movie, everything past the point where Bond is required to dress up as a clown to save the world, is just one jaw-dropping travesty after another. The big climactic set-piece involves a team of circus performers storming the bad-guy’s fortress in their circus costumes, including a team of women in leather bikinis toting tranquilizer guns.

No wait, I almost forgot, before Bond dresses up as a clown he must dress up as a gorilla.

For some reason, the title song is not titled “Octopussy.” Rather, Rita Coolidge sings a soft-rock number called “All Time High.” To sing as song titled “All Time High” for a movie titled Octopussy strikes me as either the definition of hubris or the epitome of faith.

CONTEST! I invite my readers to come up with a title more childishly offensive and stupid than Octopussy. It must involve (a) a pun, (b) a Latin word for a number, and (c) a vulgar name for genitalia (male or female will do). I’ll start: Septemember. (I had another involving the word “Prime” but it was too disgusting even for this journal.)