James Bond: Skyfall part 2

Skyfall is easily the most elegantly directed Bond movie. Bond movies date back to the early ’60s, the tail end of the “big producer” era, and EON Productions, which has produced Bond from the beginning, retains its hold on the stylistic choices made. No actor, no director is a bigger “star” than James Bond. It’s rare to see any kind of point of view from behind the camera. Bond movies are generally directed by skilled journeymen, directors who can organize a complicated set, deal well with actors, juggle egos, make their days and not go over budget. I remember watching Die Another Day with James Urbaniak, and him mentioning that he couldn’t remember seeing a less-intentional directorial style, and I feel like Die Another Day is actually one of the more stylish of Bond movies. Skyfall‘s direction is not merely skillful and elegant, but has a specific point of view. Spielberg, Scorsese and Tarantino have all mentioned wanting to make a Bond movie, and while I think the ship has sailed for those guys, I wonder if perhaps we’re approaching the point where a genuine stylist might be invited to put their stamp on the biggest franchise in history.

(Skyfall benefits not only from Sam Mendes’s direction, but also from the Coenesque team of Roger Deakins as DP and Dennis Gassner as production designer, surely the greatest artists working in those jobs today. Indeed, apart from Ken Adam, I can’t identify more talented people to have ever worked on a Bond movie.)

The “Bond title sequence” has been a feature of that franchise from the very beginning. Maurice Binder, who constructed all the titles from Dr. No to License to Kill, has to be counted as one of the most influential artists of the 20th century. Here we are, fifty years later, still trying to top him at the game he invented. Skyfall‘s titles acquit themselves very well — lush, evocative, thematically dense, telling the story of the movie in dream symbols. One of my readers suggested yesterday that Skyfall is perhaps all in Bond’s mind as he plunges to the bottom of the river in Turkey, and the titles certainly suggest it. The swirling hole that swallows Bond up at the top of the sequence suggests the rifled gun barrel that has been Bond’s logo from the beginning, suggesting that Bond isn’t merely drowning in a river, but drowning in his past. “The past” has haunted James Bond at least since Diamonds Are Forever, and Bond movies have been referring to themselves since From Russia With Love. Bond has been trotting around the world for fifty years now, aging, then becoming young again, then aging again, sometimes keeping in touch with past selves, sometimes throwing those past selves. To me, it’s weird enough that Daniel Craig shares an M with Pierce Brosnan, since Craig is a definite reboot, but the repeating M only scratches the surface of the weird temporality that Bond inhabits.

But we’re here to talk about the screenplay.

M has a problem. This, in and of itself, is unusual for a Bond movie. Judi Dench took over the role in Goldeneye and has absolutely crushed from the beginning, drawing far more intelligence, vigor and psychological depth from the part than any of her predecessors. I can’t remember giving a moment’s thought to how M might feel about things in, say, The Man With the Golden Gun or Diamonds Are Forever. He was just a dusty old father figure for bad-boy Bond to disobey. Making M a woman, and thus a mother figure for Bond, was a stroke of genius and led us to this great progression of interest in the character. Bond obviously has problems relating to women, and to give him a mother deepens not just her character but his.

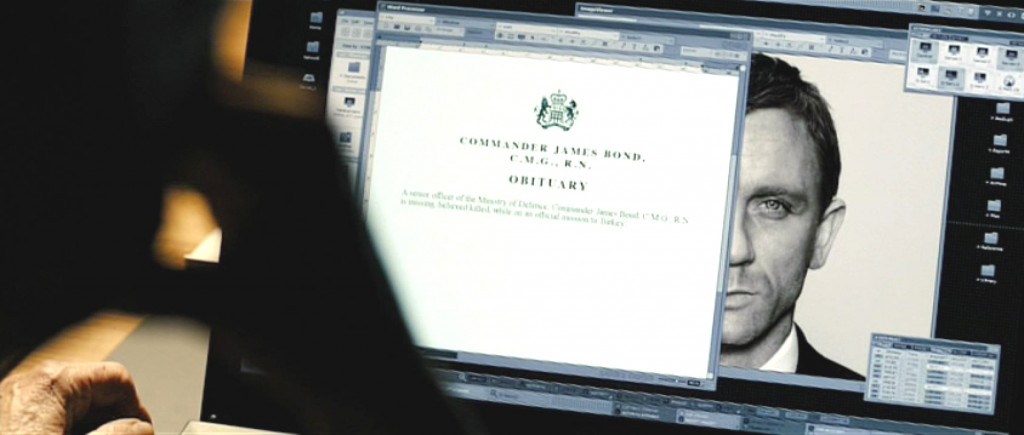

But, as I say, M has a problem. Bond is dead and her list of agents is in the hands of an unknown Bad Guy. We watch her linger over his obituary at her desk, her desk with the ceramic British Bulldog on it. The bulldog, of course, is an avatar of Churchill, and while Judi Dench isn’t old enough to have held M’s job that long, the bulldog on her desk suggests that she was born into government work, that perhaps her father was in MI6 before she was, but certainly that she is connected in a personal way to a high point in British history. Churchill, if nothing else, was a great inspiration for the people of wartime Britian (this is WWII we’re talking about, for the benefit of my younger readers), his “We will fight them on the beaches” speech was a rallying cry for national purpose. M’s problem, extending beyond Bond’s death and the loss of the list, is that the kind of war that Churchill fought doesn’t happen any more — there is no national enemy to fight against, no clearly marked armies marching, no swastika-bedecked planes bombing rainy London. M’s problem is, ultimately, an internal one — how can she do this job, this job where she favors one man’s life over another’s, every day, when she doesn’t know what she’s fighting for? She took the job at the end of the Cold War, which was a challenging enough time for Bond, thematically speaking, and espionage has only become more vague and discomfoting since then.

M’s tender lingering over Bond’s obituary (she’s taking a break before completing her topic sentence) raises an important question, not just for Skyfall but for Dench’s M in general. What is Bond to her? We know what Bond is to us, he’s the reason we came to see the movie, but why is Bond special to M, or to MI6 for that matter? All agents are, no doubt, considered and trained and fretted over, but the narrative construction of Skyfall and the history of Bond suggests that Bond is some sort of special case, as though he were Harry Potter (like Bond and Bruce Wayne, another orphan), the only boy who can defeat He Who Must Not Be Named. (In M’s case, literally — she doesn’t know the name of whoever has her list. My reference to Harry Potter is a joke, but then again they cast both Voldemort and Mrs. Malfoy in the movie, Harry Potter couldn’t have been that far from the minds of the producers.) (To torture the gag, the villain of Casino Royale, Le Chiffre, has a name that is literally not a name — it means “the number,” or, more accurately, “the cipher,” indicating that Le Chiffre could be literally anyone. And that, really is M’s problem — she’s dealing with an espionage world where anyone can be anyone, or, as the New Yorker cartoon put it, “on the internet no one knows you’re a dog.“) Is Bond a Special Case? Does he occupy a secret drawer in the file cabinet of M’s heart? Is he, in fact, a favorite son?

One thing is for sure, M is not a favored daughter. (For what it’s worth, Judi Dench played Regan, not Cordelia, at the RSC.) She’s called to the office of this guy Mallory, who appears to be superior to her in the government. We suspect him immediately, of course — not only is he Voldemort, he’s freaking Amon Goth, Hades and Francis Dolarhyde, for crying out loud. At any moment we expect him to turn into a snake or shoot lightning out of his eyes. But no, Mallory is just a bureaucrat, junior in years to M, but senior in office. This is an important distinction because Mallory is here to tell us that M is on her way out, because of the Istanbul fiasco, and, in spite of him calling her “Mum” as Bond does, there is no indication that Mallory considers M a mother or sister or daughter or sexual conquest. But, perhaps, he thinks of her as an estranged spouse — the meeting has the air of a breakup, and M certainly reacts as a woman who’s been dumped by a man she thought she could trust.

Mallory has two paintings hanging up in his office, dusty looking 19th-centure landscapes from the look of them. Who’s paintings are they? Are they Mallory’s property, or did they come with the office? Mallory is only 50, younger than the Bond franchise, why does he have such old paintings in his office? It might sound silly, but the significance of paintings in Skyfall rears its head occasionally, and I notice that Mallory, in addition to the two landscapes, has a space for a third painting, one that’s recently been taken down. Why was it taken down? There are some cardboard boxes in the corner, is Mallory planning on moving his office (foreshadowing)? Does that mean that the two paintings belong to the office but the third, the one that’s missing, is Mallory’s? It’s not a coincidence, because Mallory’s office is a set and it’s indicated that “there is a space on the wall where a painting used to be.” I don’t know if it’s a piece of production design or if it’s mentioned in the screenplay, but paintings do come to signal narrative shifts in Skyfall.

M, chagrined, leaves Mallory’s office and heads back to her own (interesting, that Mallory’s offices are quite a bit stodgier than M’s 1980s office complex — it gives the air of the establishment bringing the whippersnapper to heel). On the way, her assistant informs her that whoever stole her list has hacked into the system. Tracing the signal leads back to M’s computer itself. “THINK ON YOUR SINS” is the message that pops up on her laptop just before her office explodes.

M’s sins, of course, we’ve already seen in action — she gets agents killed, she places one agent’s life ahead of another’s. That’s her job, and she is by her own admission in over her head. But what mother does not feel in over her head? If M’s sin is being a bad mother, is her sin the original one? Is Mallory dad to M’s mum, the distant father preparing to come home?

I should’ve saved my comment on the title sequence for this part, looks like! 🙂 I’ve noticed that when most people see Ralph Fiennes in this movie, they always reference Harry Potter…nobody ever mentions the other British landmark, specifically in the spy genre, that he has a connection to.

I’m actually surprised that people mention Voldemort at all, it’s not like Mallory, or Fiennes for that matter, resembles Voldemort in any way. My son sure didn’t pick up on it.

Fiennes has two connections to British spy drama. One is The Avengers, which has been completely forgotten at this point (although it wouldn’t be the first time John Steed would show up to play second fiddle to James Bond — Patrick Macnee is in A View to a Kill. The other is The Constant Gardener, which is a great movie but not really an institution.

“The swirling hole that swallows Bond up at the top of the sequence suggests the rifled gun barrel that has been Bond’s logo from the beginning, suggesting that Bond isn’t merely drowning in a river, but drowning in his past.”

Not only that, but if you not the three other swirling holes, they all combine to create a skull like image, which is the calling card of the movie’s still-unnamed villain, at this point…but this being an anniversary film, there are plenty of references to Bond’s past, if not his previous missions (which don’t count w/ this rebooted version of the character), at least in a subtextual fashion.

NOTE* the three other swirling holes…

I tried to sum up which references were to which movies here – http://mehlsbells.wordpress.com/2012/11/23/art-of-the-title-skyfall/ – I’m sure I missed some, but it’s all brilliantly well done.

I thought they were saying “mum” the first time around, in Skyfall and Quantum of Sollace, but I’ve become convinced they’re just saying “ma’am”. The mother parallels are pretty explicit, so maybe the ambiguity is intended, but it seems like the character M wouldn’t abide being called mum by Bond, let alone her assistant, Eve, et al.

They’re definitely saying “ma’am” – the English pronounciation of this sounds like “mum” to American ears. “Mum” is the English equivalent of “Mom” and I’m pretty sure they wouldn’t have intended anyone to hear it as “Mum.” Not only would it be absurd to think that anyone (especially an Englishman) would call a boss or colleage “Mum” it would also be a crass literalisation of any intended subtext.

It’s just how we Brits say “ma’am”. Or how we would say it, if anyone ever did.

I missed it the first time, but it’s interesting that M apparently has Bond staring at her as she writes his Obit.

I’m also certain the “Mum” both Bond and Mallory use is actually “Ma’am”.

(Also, towards the end of the film, wossname presumably assumed “M” was short for “Em”, as in “Emma”.)