Hail, Caesar! part 3

Eighteen minutes into Hail, Caesar! we are treated to a water ballet number from another one of Capitol Pictures’ production slate, Jonah’s Daughter. The sequence is quite long and involved, with dozens of synchronized swimmers, a mechanical whale and Scarlett Johansson in a mermaid outfit. Hail, Caesar! takes care, when presenting its movies-within-the-movie, to present the finished product, as though complex sequences like the one shown here or the shootout in the Hobie Doyle movie are shot live by multiple camera. The Coens are careful to save their “cutting to reality” jokes for key moments; they otherwise give these Technicolor spectacles their due, letting us luxuriate in the tactile thrills of their sumptuous production values. Which makes me think that the title, Hail, Caesar!, isn’t meant ironically; the Coens really intend their movie to be a heartfelt salute to “capital” and the colorful fantasies it provides for the people.

And although the title of the mermaid picture is only fleetingly mentioned in an earlier scene, the whale is very much present, and we are reminded that the tale of Jonah and the whale is, like Hail, Caesar! ATOTC, also from the Bible, although from the Old Testament, the one with the “angry God” mentioned in the scene with the religious leaders. So an examination of the story of Jonah is in order.

From Wikipedia:

Jonah is the central character in the Book of Jonah. Commanded by God to go to the city of Nineveh to prophesy against it “for their great wickedness is come up before me,” Jonah instead seeks to flee from “the presence of the Lord” by sailing to Tarshish. A huge storm arises and the sailors, realizing that it is no ordinary storm, cast lots and discover that Jonah is to blame. Jonah admits this and states that if he is thrown overboard, the storm will cease. The sailors try to dump as much cargo as possible before giving up, but feel forced to throw him overboard, at which point the sea calms. The sailors then offer sacrifices to God. Jonah is miraculously saved by being swallowed by a large whale-like fish in whose belly he spends three days and three nights.[3] While in the great fish, Jonah prays to God in his affliction and commits to thanksgiving and to paying what he has vowed. God commands the fish to spew Jonah out.

How extraordinary that Eddie Mannix is producing a movie inspired by this story. Jonah is told by God to go preach to Ninevah, but doesn’t think he’s up to the task and flees from God’s command. God answers his reluctance with a storm, but then offers him salvation with a whale. In Eddie’s world, we see no indication of his fleeing from his God’s (Mr. Schenck) command, but we do see him terribly worried about disappointing Jesus (even though he doesn’t know a lot about Jesus). I think Eddie is a man who feels that he should be devoting more attention to God, but instead spends his time in activities of desperately earthly nature, even though he himself has only one vice, cigarettes.

The Jonah’s Daughter sequence tells the story of Jonah in a compact, abstract form, and adds a twist. DeAnna Moran (the mermaid) is shown seeking undersea treasure, and is swallowed by the whale presumably as a punishment for her greed, her attachment to earthly things. The whale then spews her out (she gets to keep the tiara that was in the treasure chest), just as it did Jonah, and DeAnna is shown “reborn,” holding Neptune’s trident. That is, she went to the treasure seeking gain, underwent a trial, and now emerges as something greater than she was before (with utterly inappropriate cross-religion symbology). It’s all there — pursuit of wealth, danger, beauty, trial and redemption. The difference between Jonah’s daughter and Eddie Mannix is that Eddie can’t honestly be said to be pursuing wealth for its own sake. When we finally see where Eddie lives, it’s a modest house with middle-class trappings; he only pursues wealth for the sake of his Caesar Mr. Schenck.

What does DeAnna Moran want? Immediately, she wants out of her mermaid costume, her “fish ass” as she puts it, because she’s pregnant and it doesn’t fit her anymore. She can’t tell anyone she’s pregnant though, because she’s not married. And, as we will see, she also doesn’t know who the father of her baby is. I think it may be a stretch to suggest that DeAnna carries within her the Son of God, but the implication is there. Perhaps that’s why Eddie has no moral outrage towards DeAnna’s predicament, only a desire to address the problem of a starlet pregnant without a husband. To wit, Eddie wants DeAnna to get married, and soon, before her pregnancy becomes common knowledge. Eddie has had to break up two previous marriages of hers, one to a crime figure and one to a junkie, in order for the studio to save face. DeAnna, for her part, doesn’t seem bothered that the studio controls her love life, she just doesn’t want to marry another louse.

Eddie lays it out for her: “The public loves you because they know how innocent you are.” Which DeAnna cannot disagree with. It’s a parallel to the religious-leaders scene, where they fight about the nature of God but agree that Baird Whitlock is “a prestige talent.” Everyone in Hail, Caesar disagrees about everything, except the ability of motion pictures to charm and entertain, to form powerful images that alter people’s minds.

(Side note: the word “prestige” has a common root with “prestidigitation” and, for that matter, the magician’s exclamation “Presto!” That is, it refers not to “quality” but to “illusion.” One hires “a prestige talent” not to demonstrate the bona-fides of one’s vision but to obscure its lack of quality. Capitol Pictures, it could be said, deals primarily in prestige, creating glossy entertainments that, at root, are pretty stupid. Or are they? After all, as Leonard Cohen said, “There’s a blaze of light in every word, it doesn’t matter which you heard, the holy or the broken Hallelujah.” Another way to sum up Eddie’s life is that he is a manufacturer of broken Hallelujahs.)

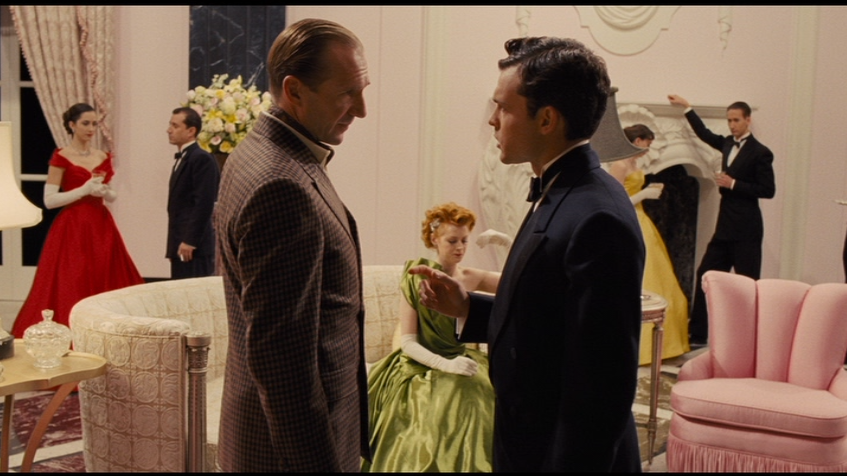

Eddie goes to talk to “Arnie Seslum,” a musical director whom, DeAnna is “pretty sure,” is the father of her child. Meanwhile, Baird Whitlock is trundled up the 101 to Malibu and Hobie Doyle reports to the studio to appear in Merrily We Dance, the drawing-room comedy he’s been assigned to. He’s uncomfortable in his costume and utterly at sea in the surroundings, the actress he’s playing against clearly despises him and the director, Laurence Laurentz, is at a complete loss to know how to direct him. Hobie, being a “natural” talent, has no business being in this picture — and this world — of elegant sophisticates. Laurentz deals in nuance and subtext, while his movie’s surfaces are pretty and placid. Hobie, on the other hand, deals in charm and movement, and his movies surfaces are physical and exciting. It’s not that Hobie isn’t up to the task of appearing in a drawing room comedy, it’s that Caesar (Mr. Schenck) has commanded that he do so, and Hobie, unlike Jonah, does not flee from God’s command. Nor does he look down at the material or disrespect Laurentz, quite the opposite; he does his level best to address every director’s note that flies over his head. The script sets Hobie into a comic situation ordained by Caesar; the important narrative question is how Hobie deals with his task. Laurentz, on the other hand, has his own burden from Caesar to address, and his problem is different: he’s directing a motion picture, which emphasizes the visual over the verbal, and he’s got a star who, in Eddie’s own words, “can barely talk.” (As a side note, Ralph Fiennes’s performance as Laurentz is his second finest, after his incredible turn in The Grand Budapest Hotel.) Lauretnz’s response to his predicament, his insistence on Hobie fitting into a mold ill-fitting, we will find, is hilariously self-defeating.

I remember thinking the line that Hobie struggles with, “would that it ’twere so simple”, was significant to the thesis of the movie, but it didn’t seem to play out that way. Was it just an ironic comment on the lack of simplicity of its pronunciation?

I think “Would that it were so simple” applies to analysis of any Coen Bros movie.

“emphasizes the visual over the verbal” – I think you mean the opposite, right? Lauretnz’s film is more verbal.

I totally agree with you about Ralph Fiennes. I’ve thought he was a talented actor since I first saw him (probably in Schindler’s List), but lately he’s been knocking it out of the park, especially with The Grand Budapest Hotel. (I’d love to read your analysis of Grand Budapest, by the way, if you’ve a mind to delve into that one.) And have you seen A Bigger Splash? It’s an uneven film, but worth watching for Fiennes and Swinton’s performances alone.

Laurentz’s movies certainly emphasize the verbal over the visual, but, as we shall see, when you have movie star who can’t act in your drawing room comedy, the only thing to do is to throw out your script and go with what the actor can do. Laurentz, a seasoned, quality director of many fine pictures, loses his bet against Caesar and must re-frame his entire movie to match his charismatic newcomer’s physicality.

That said, I can’t believe Merrily We Dance went on to be a big hit.