Coen Bros: Inside Llewyn Davis part 9

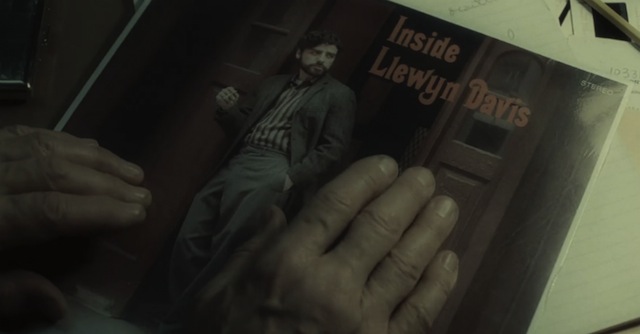

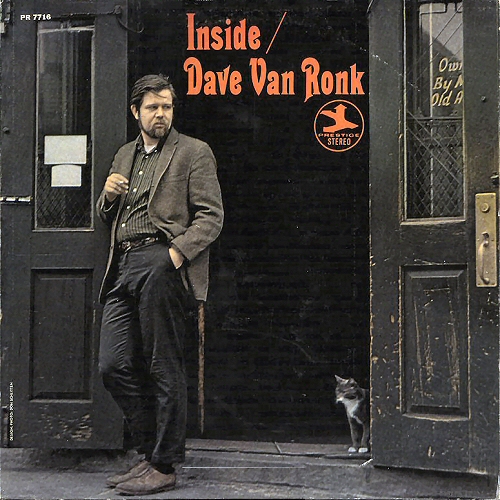

Llewyn’s album, and Dave Van Ronk’s. Complete with cat.

In the middle of the night, outside of Chicago, Llewyn falls asleep in the passenger seat. When he wakes up, the car has stopped and the police are in the middle of arresting Johnny Five. Spoiler alert!

Johnny Five doesn’t take kindly to authority figures. Maybe it’s his affection for the Beats, maybe it’s the time he spent in The Brig, maybe this particular cop is a particular asshole. In any case, Johnny gets whisked away by the police, leaving Llewyn, Roland and the cat stranded by the side of the highway. If Llewyn is a kind of dark sequel to O Brother, then Johnny Five is Llewyn‘s version of Baby-Face Nelson, the trigger-happy bank robber who blows into that narrative like a hurricane and blows out again just as fast, a manic-depressive whirlwind. Johnny Five, like Nelson, has two sides, but instead of manic and depressive, he’s laconic and volcanic, rage with a hair trigger.

In any case, he’s suddenly gone from the narrative, never to return, and Llewyn, an expert escape artist, does not think twice before he abandons the car (which is also his friend Al Cody’s car) with the sleeping, crippled Roland, and the cat who is not the Gorfein’s cat inside. The cat, that last shred of humanity Llewyn had left, is left, literally on the side of the road on a highway somewhere in the darkness of America.

Llewyn hitches a ride to a bus station and then takes a bus into Chicago, leaving Roland and the cat to their own devices. The enormity of this is kind of hard to pass up. He doesn’t even wake up Roland to tell him what’s happened, or attempt to take the cat anywhere. Nor does he try to contact any authority to alert them to the stranded car with the crippled jazz musician and the cat in it. Roland and the cat are just two more pieces of jetsam in Llewyn’s wake.

Where is Llewyn off to in such a hurry? Well, since he didn’t tell us at the top of the act, when he got in the car, he tells us now with his actions: he’s going to go see Bud Grossman at the Gate of Horn, that place where truth is told. Before he can get there though, he needs to rest, perhaps because it’s morning and the club isn’t open yet. In any case, while he’s waiting he gets ejected from a diner by an impatient waitress and then ejected from the train station by an impatient cop. Llewyn doesn’t give the cop any lip, he saw what happened to Johnny Five. He’s got an appointment with destiny (or so he thinks) and he can’t stop to be hassled by the man. He’s got to toe the line.

He gets to the Gate of Horn, which is empty (the gatekeeper is not in attendance) and huge, but the administrator on duty at least let’s Llewyn wait there, out of the Chicago cold. While Llewyn warms up (musically, if not temperature-wise), Bud Grossman, the Great Man, the man who symbolizes the ultimate authority, the man who appears in every Coen Bros movie, Capital, walks in and past Llewyn, without seeing him.

Llewyn gathers his nerve and approaches Bud in his office, as the Great Man struggles to remove his galoshes. Suddenly the Great Man is just another club-owner, struggling to get by on a cold winter’s day. Llewyn introduces himself and reminds Bud that his manager, Mel, has sent him his album. “Oh, you’re with Mel,” says Bud, with a glint in his eye that indicates that Mel is, perhaps, a manager of suckers and losers, the 1960s folk music version of ARK Music Factory. “I was just passing through,” says Llewyn, as though he hadn’t just traveled three days and left his compadres by the side of the road in order to attain this meeting. Turns out, Mel never sent Llewyn’s record to Bud, which means perhaps that Mel’s never really sold any records to anybody. Bud sighs and rolls his eyes as Llewyn struggles to get a copy of his album out of his bag. “Here it is,” his expression says, “Another fucking folk singer from Mel, another poorly-dressed loser with a guitar and a record under his arm.” In spite of Bud’s despair at Llewyn, and in spite of his disdain for Mel, Bud actually steps up. “You’re here, play me something,” he says, game and, under the circumstances, welcoming. “Play me something from inside Llewyn Davis,” he adds, with just a hint of venom in his voice. He seems to doubt that there is, in fact, anything inside Llewyn Davis. From what we’ve been seeing, we’re worried that perhaps he’s right.

Llewyn, who refused to sing for the Gorfeins, then used the opportunity to berate them, then played to Johnny Five and Roland to irritate them, faces a new task: will he, should he, play for Bud Grossman, on demand? Should he be able to put aside his pride and artistic altruism for the sake of impressing Capital, in the hopes of career advancement?

The answer, of course, is “yes.” Because LLewyn, for all his talk of artistic integrity and how advancement is for squares, is still perfectly capable of sucking up to authority, if that authority could launch his career. So Llewyn sits down with Bud on the floor of the Gate of Horn, that place where truth is spoken, and tells the truth. He sings “The Death of Queen Jane,” a song about a woman in a difficult labor. She pleads with her husband, King Henry, to cut her open so that she can be out of pain and that the baby might live. King Henry refuses; he’s worried that the operation might kill both. Because the King cannot choose, the queen dies and the baby lives.

The song has obvious literal relevance for Llewyn, who has one child he doesn’t know and another due to be terminated in a few days’ time. But what other significance might it have? Perhaps Llewyn feels that he is Queen Jane, with a great and precious gift inside himself, willing to die so that the baby might live. Perhaps he feels that he’s King Henry and Queen Jane is his music, and he feels forced to choose between killing the music to save the baby (whatever arises from a career in music) or letting both die. In any case, his performance of this woeful song is definitely sad, bitter and rueful, a real tour-de-force. And Bud Grossman’s verdict is, without question, the most devastating Llewyn could hear: “I don’t see a lot of money here.”

Because, of course, the guardian of the Gate of Horn, where truth is told, is a capitalist. And while LLewyn’s performance of “The Death of Queen Jane” might be a pinnacle of artistic truth, Bud’s verdict is the pinnacle of another kind of truth: there is no place in show business for an artist like Llewyn. And yet, Bud isn’t a heartless businessman: he mentions that he really likes Troy Nelson, the gawky serviceman from Act I. Why? Because “he really connects with people.” Llewyn, both literally and artistically, does not connect with people, he’s a stubborn individualist, albeit an individualist who requires a raft of people to support him and his individualist ways. Bud, in a moment of compassion, even offers to put Llewyn together with a trio he manages (presumably Peter, Paul and Mary, who were created by Albert Grossman and for whom Dave Van Ronk auditioned, and was rejected for being too uncommercial). Llewyn turns Bud down, which, if you know anything about folk music, is a super bonehead move: within a year, Peter, Paul and Mary would be a million-selling group, the spearhead of the folk movement and a skyrocket that would bring Bob Dylan to national prominence with their recording of “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

Bud suggests that Llewyn get back together with his partner, not knowing that Llewyn’s partner is dead. “That’s good advice,” says Llewyn, his path now officially cut short. It’s one of the best scenes of the American movie year.

Here are the Coens commenting on how they chose ‘The Death of Queen Jane:’

http://www.vulture.com/2013/12/toughest-scene-i-wrote-the-coens-llewyn-davis.html

I did see that! I wish it actually said how they chose the song, or why the scene was “the hardest I ever wrote.”

I also wonder if Mel actually sent the album, but Grossman just couldn’t be bothered to listen to it…

On the subject of Gate of Horn, have you ever heard this song by Roger McGuinn? http://youtu.be/lj3M0km1lPg