Batman: The Dark Knight Rises part 5

The next step on Bruce Wayne’s road to recovery is stopping in to see Lucius Fox, the inventor to whom Bruce entrusted the running of his company back in Begins. Lucius finally brings Bruce’s monetary woes into focus — he spent his entire research-and-development budget on this mysterious “save-the-world” project, then cancelled it, leaving Wayne Enterprises ripe for takeover by industrial predator Daggett. (If Harvey Dent was Daytime Batman, John Daggett is Overground Bane, taking over Bruce’s legitimate business while Bane prepares to go after his darker identity.) Note that the screenplay still doesn’t tell us what the project is, exactly. Because what the project is is the maguffin of the piece, and if we know what it is too soon, it tips the narrative’s hand in undesired ways. Suffice to say that the comely Miranda Tate was instrumental in developing said project, and that Lucius strongly supports Bruce settling down with her. And, when Lucius is played by no less a personage than Morgan Freeman, the viewer takes it on faith that if Lucius wants you to settle down with a particular woman, you should probably do that.

Batman: The Dark Knight Rises part 4

With Jim Gordon hospitalized, John Blake emerges as a significant secondary protagonist in The Dark Knight Rises a kind of “young Gordon.” What does Blake want? Blake wants Bruce Wayne to stop sitting around feeling sorry for himself and become Batman again.

Now then. Some have expressed discomfort with the idea that John Blake, Rookie Cop, knows that Bruce Wayne is Batman while neither Jim Gordon nor any other citizen of Gotham City has apparently even given the matter a moment’s thought. This, for me, goes hand in hand with other narrative contrivances that occasionally poke through the cloth of Nolan’s Batman trilogy. The presentation and production design of these movies is so grounded, so realistic, it’s easy to forget Batman’s pulp roots, nay his operatic roots, and moments like “Blake knows Bruce Wayne is Batman,” in my experience, are endemic to the genre. I’ll say it again, the moment you decide to make a movie about a man who dresses up like a bat to fight crime, you enter the realm of the fantastic. The reader may remember my analysis of Batman and Robin, where I discovered that the psychedelic outrages of that screenplay all stem from the choice of making the flamboyantly fantastical character Mr. Freeze the chief antagonist of the piece — once that decision was made, everything else had to be made that much more crazy to fit that character. A similar thing happens here: as much as director Nolan wants to ground his Batman movies, the fact remains that they are about a man who dresses up as a bat to fight crime. Thousands of creative and narrative choices flow from that single plot point. Since that single plot point is flat-out absurd, it greatly affects everything that flows from it. In this case, wait, why hasn’t anyone, anywhere, even tried to figure out who Batman is? If a movie tried to address that question in any realistic way we’d be here all day, and the narrative would quickly spiral out of control as the thousands of questions raised by a man dressing up as a bat to fight crime would echo down and down and down until the very thing we get out of a Batman story — that is, the metaphor — would be lost. That’s why narratives like The Dark Knight Rises needs occasional contrivances like “Rookie Cop Figures Out Bruce Wayne is Batman” (or “SEC Approves Trades Made By Terrorists at Stock Exchange”). Anyone whose disbelief crashes down at this juncture would fall down dead if the same everyday logic was pressed onto any other aspect of the narrative.

Batman: The Dark Knight Rises part 3

The time has come to ask: What does Bruce Wayne want?

We’ve seen that he’s eradicated organized crime in Gotham City, so theoretically he’s overcome the sense of helplessness he felt about his parents’ deaths — there will be no more Joe Chills running around making orphans out of billionaires’ sons. Now, it would seem, he’s looking for a way out, a way to move on, to finally emerge from his cave, bury his parents and his girlfriend (and her boyfriend Harvey Dent) and become a fully-integrated man. The Dark Knight Rises is, at its heart, a dramatization of how a world-class control freak finds a way to let go.

But “to let go,” that’s not what he wants, that’s what he needs. What he wants is the opposite: to close the world off, to brood, to pout, essentially, to consider his losses and to hell with the world.

Batman: The Dark Knight Rises part 2

We’re still at the Dent-related function at Wayne Manor, and there are still characters scurrying around to meet. John Daggett is some level of businessman, disliked by Alfred and apparently by Miranda Tate as well, a dissolute lout who opines that Bruce Wayne pounced off with his investors’ money with his “save the world” project, and offers to get Miranda her money back in his own way. Miranda, it seems, shares Bruce’s ideals and snubs Daggett. In keeping with the theme of deception, Daggett thinks Bruce has deceived his investors and Miranda thinks Daggett is deceiving her. Later, we will find that Miranda was deceiving everybody.

Batman: The Dark Knight Rises part 1

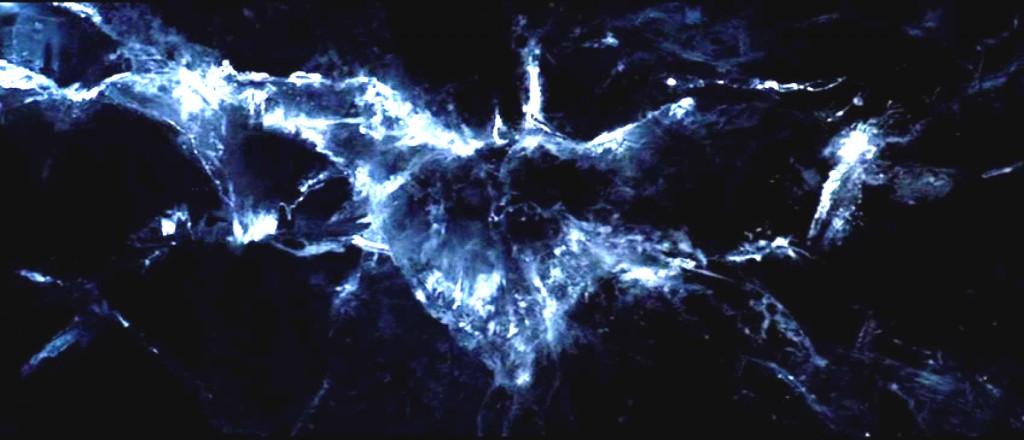

The “titles” of Batman Begins showed the symbol of a bat formed in a swarm of bats, the titles of The Dark Knight showed it in fire, now The Dark Knight Rises shows it in ice. The bats in Begins were a symbol of fear, the titles a metaphor for an identity forming out of shadows. The fire of The Dark Knight was like a wall of fire for that bat, that symbol, pushing through the chaos inflicted by the Joker. Now, the bat is, literally, the cracks in the ice formed by the isolation of Gotham City at the hands of Bane. “I knew Harvey Dent,” Jim Gordon lies, as the title image gives way to a scene of Gordon addressing a memorial service for the late District Attorney, “I believed in Harvey Dent.” Gordon is not speaking of Dent at all but of Batman, the man who (the reader will recall) took responsibility for Dent’s bizarre chance-induced crimes, became Gotham’s Dark Knight so that Dent could remain its White Knight, its Daytime Batman as it were. Thus caught up, the viewer is plunged into a new story.

X-Men: First Class part 11

The most striking, most unusual feature of the screeplay for X-Men: First Class is that it does not have a traditional end-of-second-act low point. In the typical superhero narrative, the story is: villain appears, superhero fights, villain triumphs, superhero comes back from defeat. That doesn’t happen here, because First Class, lest we forget, is a romance. The romantic comedy goes: boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl back, but a straight romance doesn’t need a happy ending, and in fact can have a tragic ending, as in Romeo and Juliet or The Fly. In the romantic tragedy, the two leads want to be together but cannot — the forces arrayed against their union are too great. The forces arrayed against Erik and Xavier are all internal, and deal with their past and upbringing, irreconcilable questions of identity and personality. Erik cannot wake up in the morning and no longer be a persecuted Jew, and Xavier, for all his psychic power, cannot imagine life in Erik’s shoes, because he’s always had everything he needs. If they could change, if they could reconcile their differences (that’s why the movie spent the first act underlining those differences), they could stay together and save the world, but the narrative drives them irrevocably toward breakup and tragedy.

So what is the structure of First Class? I would say it’s: Act I, Erik and Xavier head on a path toward each other with Shaw as their common enemy, culminating in their meeting; Act II, Erik and Xavier pursue Shaw together and fall in love through the action of doing so, culminating in the raid on the Russian general’s house; Act III, a retreat to more internal matters as Xavier attempts to temper Erik’s anger with love while he trains his recruits; and Act IV, where Erik’s and Xavier’s relationship is put to the test: can they work together, save the world and be happy, or will the polar opposites of their pasts hinder their efforts and tear them apart, simultaneously bringing the end of the world? (“The end of the world” is an overused trope in superhero narratives — hell, a lot of narratives — but when it’s tied to a love story it become elevated; a romantic breakup often does feel like the end of the world, First Class merely literalizes it.)

X-Men: First Class part 10

As the fantastic merges with the historic, no less a personage than John F. Kennedy is brought in lend weight to plot of X:Men: First Class. The footage is real, as is the footage that follows, of stores being sold out of canned goods and people stockpiling fallout shelters. Fallout shelters were big news at the time. The Twilight Zone had featured an episode about a fallout shelter a year earlier than the Cuban Missile Crisis; Bob Dylan, in February 1962, recorded a song about them, “Let Me Die in My Footsteps.” What seems quaint now, the idea that one could run and hide from a nuclear war, was, unbelievably, very real and present to the general populace. I myself was a mere tadpole in October of 1962, but my parents assured me, yes, for a few days, you pretty much just didn’t know if the world was suddenly going to end. In its way, it’s a comforting thought, that this level of madness was brought on by fantastical mutants bent on world domination, as the reality of the situation is too mind-bending to absorb.

In practical terms for the adventure narrative of First Class, the Cuban Missile Crisis is a clue for our protagonists to find Shaw. Remember, “to save the world” is not their goal, only “to find Shaw.” Xavier to stop him (to make the world a better place), Erik for his private, personal revenge. Xavier is high-minded, Erik is low-minded. Xavier may be who we want to be, but Erik is who we are.

X-Men: First Class part 9

While Erik and Xavier, er, “have their way” with Emma in Russia, Shaw and his team make their move on MiB HQ. Shaw is striking back at Xavier for poking around with Cerebro (the shots of Xavier with his head in Cerebro, ecstatic and lit from within, tie him to 60s mind-expansion gurus like Timothy Leary and John C. Lilly). First they kill all the humans, then they come for the mutants. You can come with me and be free, Shaw says, or stay here and live in slavery, and the camera points to Darwin, because, you know, slavery. In the scheme of First Class, this is like the Students for a Democratic Society (which formed in — you guessed — 1962) crashing the peace-and-love party. Shaw, of course, is no student, he’s been around forever, he’s more like an outside agitator, a warmonger disguised as one of the hip kids, fomenting rebellion because, well, that’s the business he’s in. “You can join me and live like kings and queens,” he says, looking at Angel, but we’ve seen how Shaw treats Emma — there will be no equality in Shaw’s version of the future. Angel, she of low self-esteem (she is a stripper, after all) comes with Shaw, but Darwin and Havok try to stop her. Darwin, sadly, goes from being the non-stereotypical black guy to being the stereotypical black-guy-in-the-movies, and becomes the Noble Sacrifice to the cause, the first one to die in the fight against evil.

Read more

X-Men: First Class part 8

The joyous gathering of the new X-men recruits, in the inner sanctum of the MiB HQ, echoes what was happening in college campuses all over the world. It begins with young people discovering themselves, claiming their powers, forging new identities and enjoying their commonality and diversity, and ends with one of them destroying the Establishment leader in effigy. I was struck by the moment of Havok slicing and burning the statue of the MiB (odd that he has a statue of himself on his compound) and trying to remember what it reminded me of. Then I realized, of course, it reminds me of campus protests, where all sorts of unspeakable acts are visited upon the statues of the Great White Men who built the temples of learning but whose relavence had long since vanished. The young recruits are the campus youth movement, the Other gathered in an establishment sanctuary, free from the worries of employment (stripper, cabbie), freed from imprisonment, free to concentrate on “finding themselves,” and, thus, free to concentrate on the next thing. The next thing, in college campuses, is supposed to be “studying,” and here in X-Universe is supposed to be “finding Shaw,” but the end result in both cases is the same: “saving the world.” That’s what the 1960s youth movement, the Hippie Dream, was all about, although, like with the X-Men recruits, “toppling the Establishment” (or at least thumbing one’s nose at it) is the first step in defining themselves. The reason Bob Dylan became the “voice of his generation” was not his politics, it was his refusal to be identified, to be pinned: “Whatever you say I am, that is what I am not.” That strikes at the core of the appeal of X-Men from the beginning, and First Class is not just a history lesson, but an X-Men history lesson. Other movies pay homage (or lip service) to their comics origins, First Class actually puts its comics in historical context and thus illuminates their genuine cultural import.

X-Men: First Class part 7

Erik and Xavier, two straight men in 1962, have fallen in love. Like all straight men who fall in love, they must find things to do together in order to have an excuse to hang out. The manlier the better. Hence, the first thing they do after deciding to work together to find Shaw is to go to a strip club and indulge in some very groovy Mad Men style sexist shenanigans. The joke here being, of course, that they’re not looking for sex but for mutants, in this case a winged young lady named Angel Salvador. Still, the message is clear: like James Bond, Erik and Xavier have found that saving the world doesn’t have to mean you can swing a little. Next, they find a young black cabbie in NYC named Armando Munoz, a imprisoned young man named Alex Summers, an awkward youth with a hyper-sonic voice named Sean Cassidy (not Shaun Cassidy), and, briefly, a taciturn guy named Logan, who, in the movie’s single funniest moment, politely rebuffs their advances. Even Erik and Xavier strike out sometimes, and not everyone wants to join a family.

The team that they assemble are all variations on the Other — a stripper, a black youth, a prisoner, an awkward, rejected teen boy, they’re like the cast of a Bob Dylan song come to life. We’re watching the 1960s come together. Logan, of course, had his ’60s a hundred years earlier, this is not his movement. (I also note that Armando, while black, is not black and angry, just a working-class dude driving a cab, which makes him “other” enough in 1962 New York, no reason to disenfranchise him as well, or make him a stereotype.)