The Avengers part 7

At the top of Act II of The Avengers we begin where we began Act I, in space, with The Other and Loki, checking in. They talk about The Chitauri, to remind us that that’s a thing, they talk about the mysterious boss at the other end of the jukebox, and remind us that the boss wants The Tesseract, Or Else. We also learn that Loki was once “the rightful king of Asgard,” which gives him the horse in this race. Loki may not be the Ultimate Boss of The Avengers, but he has a much more compelling motivation: revenge against his brother Thor, who exiled him. This narrative stroke, to make two characters from Thor the hinge of the screenplay, is masterful: the traditional studio approach would be to take the wild cards of the franchise (Norse gods!) and ignore them compleely, or give them only token attention. But to put Loki and Thor at the middle of this gigantic tentpole money-making machine provides a useful bridge between the mundane (Hawkeye), the fantastic-but-still-believable (Iron Man), the straight-out fantastic (Capt America, Hulk), and the gonzo sci-fi alien spectacle of The Chitauri. The mere fact that one movie embraces all these characters is daring enough, but the screenplay for The Avengers distrubutes its narratve effects so judiciously and balances its characters so well that a common, non-comics-reading audient sees a Norse god taking orders from an alien in a robe and thinks “Okay, sure, I get it.” The fact that Loki’s motivation is both human and not centered on “conquering the universe” but one-upping his good-looking brother gives the narrative an appreciable scale and, thus, creates audience involvement in something patently absurd.

The Avengers part 6

Perhaps the most impressive feature of The Avengers is the way it balances the separate stories of its wildly disparate leads, so that we never, ever feel like “Oh, another Thor scene, ho hum, I guess it will end soon.” The screenplay keeps so many balls in the air that everything feels lively and inventive and fun, even when the plot isn’t being forwarded, or especially when the plot isn’t being forwarded. The balance of the superheroes is so strong, here it is, twenty-three minutes into the movie and we are suddenly thinking “Oh yeah, Iron Man is in this movie too, I totally forgot.”

What does Tony Stark want? Tony Stark wants to show the world that the machine that powers his heart, and his suit — his life, really — the Arc Reactor, is also a viable energy source. “Energy,” in this instance, is just another word for “power,” and power is what superhero narratives are all about — who has it, who does not, who wants it and what they will do to get it. In the case of Iron Man, “power” defines the two sides of Tony’s life — he is both a weapons merchant, a power broker of the purest kind, and a power provider, with his Arc Reactor. He bets both sides of the coin, even if he stops selling weapons, he is still a weapon himself, a walking, thinking weapon.

Of defense, of course, which is always the problem of a superhero narrative — if the protagonist has more power than those around him, he must, must use that power in defense of those people. The trick is how to make that character interesting, to not make him a Boy Scout. Batman makes its protagonist obsessive and brooding, Hulk makes its protagonist an agonist who doesn’t want to use his powers at all, and Superman — well, that’s part of the reason why Superman is so hard to do in a cinematic narrative, he’s both a boy scout and resolutely unbeatable. Iron Man, on the other hand, makes its protagonist kind of a jerk — flawed, vain, conceited.

Who has power in The Avengers isn’t as interesting as who wants it, and who loves it. Thanos, apparently, has all the power in the universe, except for that one thing. The Other, it would seem, has as much power as any being could hope for — he towers over Loki, a freaking god already, and has armies at his disposal, but is a mere lackey in the presence of Thanos, and a bootlicker at that. Contrast him with Nick Fury, who also must report to a mysterious disembodied power, his committee, but who holds them at arm’s length, with distrust, and wants primarily to create a family. Then contrast Fury with Coulson, who is polite and diffident with Fury but holds a stunning amount of his own power, then contrast Coulson with Tony Stark, who treats Coulson like a teaching assistant he has to be nice to.

The Avengers part 5

We now scoot over to India, where we meet Bruce Banner. Or rather, first we meet a little Indian girl, who dashes through a slum in search of Dr. Banner to aid her dying father. The little girl’s desperation is palpable, and the good doctor can hardly help but follow her. Our hearts go out to the little girl, and we desperately want to see Dr. Banner help her father. Like everything in The Avengers, this is played out very quickly but with great efficiency. A little drama is created, as our protagonist shifts from Nick Fury to Black Widow to this little girl on her mission to save her father. And, because the direction is so sure and the production design so convincing, we accept the truth and stakes of the girl’s plight.

The little girl, it turns out, is bait, set by Black Widow to capture Bruce. The little girl, in her helplessness, plays on Bruce’s good nature and feelings of sympathy and gets him to go to an empty house. There’s a wonderful moment just before they get to the house where the police roll by and Bruce shields the little girl with his body, as though keeping her out of the hands of the authorities. He is, of course, keeping himself out of the hands of the authorities, but he plays the moment for the sake of the girl, as “the caring father.”

Kurt Vonnegut once said “We are what we pretend to be, so we must be very careful what we pretend to be.” This applies to no one in the comics universe more than Bruce Banner, who must be very careful indeed what he pretends to be. His life as a doctor is, in its way, a performance, or an act of contrition, a way to pay for the things he does as “the other guy.”

When the little girl leaves Bruce like a groom at the altar, we realize: the little girl isn’t just like Black Widow, she is Black Widow, using the patented Black Widow technique of getting men to let their guard down by putting on a weak-and-helpless act.

Read more

The Avengers part 4

Now that our movie has a protagonist, the question, as always, is “What does the protagonist want?” Superficially, the protagonist of The Avengers, Nick Fury, wants “to save the world,” that most generic of motives. To save the world, Fury must get a group of superheroes from vastly different backgrounds to work together.

Surprise! What the protagonist wants is exactly the same thing as what the writer-director wants! If Joss Whedon cannot succeed in getting his dog’s-breakfast of a cast to mesh, meld and work as a unit, his narrative will fail and no one will go see his movie. This not only gives the writer a keen insight into his protagonist’s character, it’s a stroke of genius, giving the narrative a spine that would otherwise make it an ensemble comedy-spectacle, an It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World with superheroes.

The Avengers part 3

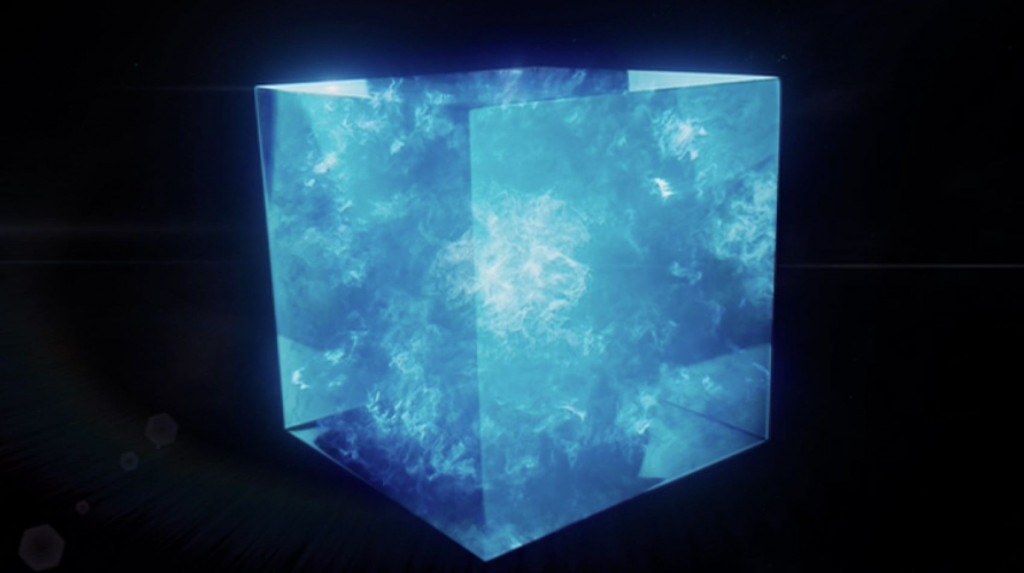

Our protagonist, Nick Fury, gets out of his helicopter, along with his sidekick Agent Maria Hill, and exchanges some rapid-fire dialogue with Agent Coulson as he heads down, down, down into the depths of the installation. He’s arrived in a helicopter, a symbol of power, and now he descends deep, deep underground. What does he talk about with Coulson? “A bunch of stuff.” The Tesseract, we come to understand, has done something surprising, which has necessitated the evacuation of the installation. The Tesseract, which, again, we don’t know what it is or what it does, is kept deep, deep underground because it’s so freaking powerful.

(Incidentally, why must the installation be evacuated? The answer: because The Avengers, in order to make the ton of money it needs to make, must be rated PG-13. The installation is about to go sky-high, so to speak, and if the movie begins with a catastrophic loss of life, it becomes Saving Private Ryan instead of the colorful spectacle it needs to be.)

The Avengers part 2

At the end of the last post I mentioned “stakes.” An important thing to understand about stakes is that they are directly related to the success of a cinematic narrative. When the stakes are low, the movie feels “small,” and the narrative decreases audience involvement. A movie about a guy who loses his keys is going to be less involving, to most people, than a movie about the end of the world. On a macro scale, less audience involvement generally means less audience. When the stakes are life-or-death, audience involvement increases. So The Avengers takes care to mention, right up front, that nothing less than the fate of all humanity, and the universe, is at stake. Not the planet, not the solar system or even the galaxy, but the universe. Obviously, this movie is playing for keeps.

The Avengers part 1

In the coming weeks, there will be much discussion of what the “best screenplay” of 2012 is. The Avengers will probably be absent from that discussion. That’s a shame, because the screenplay for The Avengers is a startling model of precision, density and propulsive narrative. It manages to balance no fewer than ten wildly disparate main characters in its ensemble cast, but gives each of them weight, clarity and purpose. Dear readers, I’ve worked on many a comic-book movie, none of which ever got near production. Getting one superhero narrative to work is damn near impossible; The Avengers has a screenplay that soars with seven.

A note on The Avengers

You know, it’s quite good.

And it appears the entire world wants to see this movie about a scrappy band of misfits who put their differences aside and refuse to bow down to an individual who would oppress them.

Many years ago I went with my friend R. Sikoryak to see the first Sam Raimi Spider-Man movie. R. had been waiting all his life for that movie, and it did not disappoint him — it all felt right to him. I wasn’t well-read in Spider-Man comics at the time, so I assumed he was right.

Looking back on it now, Spider-Man is a wonderful movie, but does it capture the tone of the comics? My reading of Spider-Man was that he wasn’t so tortured, that he wore his heroism lightly, that he was always there with a quip, that nothing really bothered him that much — as long as he had his Spider-Man suit on, anyway. The act of putting a teenager in a Spider-Man suit on film, I think, meant that the character and his world needed to become — here’s the dreaded word — “grounded.” And the Raimi movies got that down well. When you take a character in spandex and put him on screen, he’s bound to look ridiculous. Because of that, everyone in the movie must take this all very seriously, or else there is no dramatic tension.

Look at where we’ve come in this genre from the Batman TV show to The Avengers. The Batman creators saw that a man dressed like a bat punching people was ridiculous, and so everyone played it for laughs. The Superman movie creators saw that a little weight could add resonance to this pulp material, but they had no real faith in the source material. Deep down, they thought it was all kind of silly and gave Superman a buffoonish Lex Luthor to fight. Look at a project like Justice League of America: The Movie and you can see how disastrous a too-light approach can be to this kind of material. How can we care about anything onscreen if everyone is an idiot?

The Avengers, I think, gets it all right, more so even than X-Men: First Class, up ’til now my favorite Marvel movie. The characters are well drawn, well played, taken seriously and grounded, but it all plays very lightly, the way I remember Avengers comics being. Disaster always looms, the world is always on the brink of collapse, but everyone in the movie manages to bear the burden with a grin. I mean, we’re talking about a world where a thawed-out super-soldier, a Norse god and a Jekyll-and-Hyde monster all live in the same space, where an aircraft-carrier can fly, where the multi-billionaire arms dealer with the flying super-suit is the most “grounded” character of the bunch.

Add to this the fact that the movie has to juggle the concerns and arcs of no fewer than ten main characters, and does so with grace, humor and panache. There is never a moment where you’re thinking “Come on, where’s the Hulk already?” or “Ugh, Captain America, I’m gonna go get some popcorn,” but neither does the movie get so bogged down in any one character’s struggles that the narrative slows.

And we remember, we read superhero comics as children because they were fun. The adventures were huge, the mayhem panoramic, the tests of will and strength arduous, but above all, they were fun. The Avengers remembers that.

Avengers Defeat Galactus!

This was the scene early yesterday morning in Sam’s bedroom, where one of the most fearsome titans in the universe was soundly defeated by the Avengers, aided by members of the X-Men and the Fantastic Four. Ben Grimm stood proudly upon the stomach of the fallen giant and surveyed the scene with a calm wisdom while Iceman, Spider-Man, Logan and Bishop covered the lower half of this seemingly unbeatable foe.

The Hulk stomped out the eyes of the intergalatic plunderer and gave a triumphant roar of “Hulk smash!” while Professor Reed Richards plunged his elastic arm deep within Galactus’s ear to scramble his brains.

Among the fallen was a collection of villains formidable in their own rights, but puny mortals compared to the immense, god-like Galactus. Left to right: Sabretooth, Magneto, Dr. Doom (his gun still clutched in his cold, dead hand), Dr. Octopus and Juggernaut.

Iron Man was unable to participate in the attack on the supervillains, as he was out of scale. He had to be content with providing moral support from the headboard.