Okay, God, let’s have it out. You and me.

I gotta say, you’ve done some pretty weird shit in your life, but there are limits, okay? Katrina, I can’t figure that one out — what was the point of that? And then the Southern California wildfires. And the tsunami. And the droughts.

I get it, I get it — you work in mysterious ways. I’ve been paying attention, I get it.

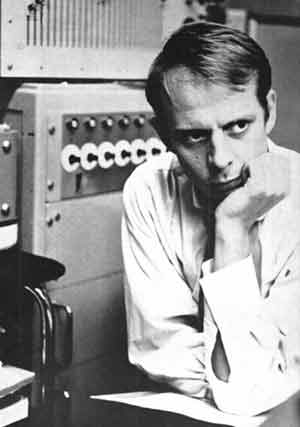

But, please, give me a clue. Help me understand. Why on Earth, in the course of five billion years of our planet’s existence, would you possibly need to take Karlheinz Stockhausen, Ike Turner and — gasp — Dan Fogelberg all in the same week?

Let me try to parse this latest act of bizarreness. You’re up in Heaven, and you say “Hey, you know what we need up here? Some dense, impenetrable German avant-garde music!” So you call Karlheinz and he shows up and you hear the kind of stuff he does and you say “Okay, okay, it’s good, but you know what it needs? It needs a beat, you can’t dance to this stuff, who really knows how to turn a beat down there?” And so you grab Ike Turner and you put these two sounds together. It sounds like it would be super-ugly to me, but what do I know, maybe the clash of high German weirdness and deep American grooves sounded great, but the only thing I can think is that it sounded a little, you know, heavy, what with the postwar anomie and the wife-beating and all that.

That’s the only justification I can see for adding wimpy folk-rocker Dan Freaking Fogelberg to the mix. Have you even heard this guy before? Can you even begin to imagine the world of pain your ears are in for, trying to weld together Stockhausen, Turner and Fogelberg?

And who’s going to be next? Christ, who’s going to have to show up to this jam session to meld together all these sounds? Bassist from Ratt? Yma Sumac? Ornette Coleman?

Star Wars Episode VII

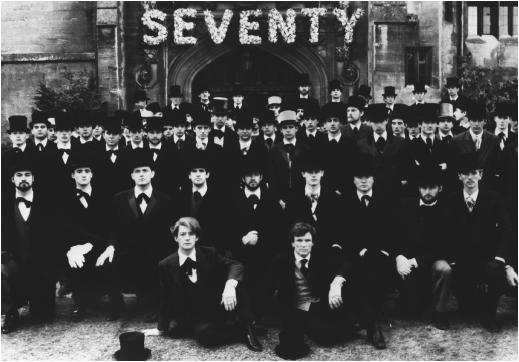

Produced, written and directed by Sam Alcott (6). Edited by Todd Alcott. Performers: Sam Alcott and Todd Alcott.

This movie was created under the strict supervision of Sam. The shot list, scene order and camera placement were all his (with occasional input from me). When you hear me say a line of dialog, I am saying only and exactly what Sam has directed me to say. (In certain cases we had to do several takes of a scene because my voice was not right or I improvised too much with Sam’s dialog.) It was shot entirely on a Sony Cybershot, a digital camera designed to take still photos and short movies.

Sam has picked up the lingo of moviemakingvery quickly. He will ask if we’re rolling and understands the commands “Action,” “Cut” and “Pull back,” and soon I’m sure will be saying things like “Okay, now I want a steady tracking shot along this way, then push in close to here, then we’ll cut to a close-up of the girl’s face reacting.” He has an innate, if incomplete, understanding of cutting techniques and carries the whole movie inside his head. On occasions when I left out a scene I thought was confusing or dragged the narrative, he would see the gap immediately and instruct me to put it back in. As a result, I felt it would be best to insert some titles to help explain the action, which might not be immediately apparent to non-aficionados.

PLOT SYNOPSIS: General Grievous is planning some kind of attack on Kashyyyk. The Clone Army arrive and foil his plans. Grievous sends his troops to fight the clones but they fail (these scenes were not shot). Grievous then attacks the Jedi himself, killing several of them. The Clones then receive “Order 66” from Darth Sidious, which causes them to attack the Jedi. Yoda and Obi-Wan fight the Clones, and Obi-Wan kills General Grievous and wipes out the remainder of his forces. Then, for reasons that elude me, the ending of Episode III is recapitulated.

(I am being disingenuous — I know why the ending of Episode III is recapitulated — it’s Sam’s favorite part of the whole Star Wars saga, specifically the fight between Obi-Wan and Anakin on Mustafar. The mining apparatus and volcanic surface of Mustafar are here represented by a credenza, a chair and a Disney Princess scooter (belonging to Sam’s little sister).

Sam was disappointed with the final cut only because he hadn’t thought his hands would be so visible in the shot. In his mind, the characters moved and acted the way they do in the movies. He instructed me to digitally remove his hands and body from the shots. When I explained that that is possible but cost-prohibitive, he said “But we could scan the movie into Photoshop and erase all the parts we don’t want.” When I told him that that would involve working on literally thousands of individual still frames, he relented. But I think the boy has a future.

Coen Bros: O Brother, Where Art Thou?

I clearly remember seeing this movie for the first time. I was in Paris with

and our wives and we were all very excited to see the new Coen Bros movie before it opened in the US. Before the title sequence even began, I knew that I was watching a singular work of genius.

And there in my seat in the small, boxy Paris theater (it was, literally, the last day of the movie’s run in France) I thought “You know what would be a good idea for a movie? A movie that shows the evolution of American music, beginning with its roots in slavery, showing how it springs from both broad sociological movements, yes, but also ties it to the specific rhythms of the everyday activities of the people performing it.” And then the movie began and I realized I am watching that movie right now.

(If you’ve never done it, it’s a real treat to watch an American movie, especially a comedy, with a foreign audience. They laugh at the jokes a few seconds before you do because they read the subtitles faster than the actors can speak.)

O Brother, Where Art Thou stands as the Coen Bros warmest, most expansive, most generous, most delightful, most optimistic movie. That it does all those things without having a proper plot is something of a miracle.

THE LITTLE MAN: Ulysses Everett McGill and his compadres (seemingly the only three white people in prison in Mississippi, who all happen to be chained together), like many Coen protagonists, seek a treasure, the suitcase full of money that will transform their lives and make them worth living. As with most Coen movies, the search for, control over and lack of money is the driving force of the narrative.

Now look at where that money comes from. According to Ulysses, the treasure was stolen in an armored car heist. That would make the money the possession of “the bank,” an institution that lost favor in Depression America for foreclosing on mortgages (which gave a bank robber like Baby-face Nelson heroic status, despite being a certifiable pyschopath). So Ulysses is a criminal, uniting with two other criminals to pursue money gotten in a crime, which was in turn gotten by banks in the act of what was widely perceived as another crime. Ulysses and his pals don’t find their treasure (because, of course, there is no treasure) but they do find success as recording artists, getting paid $60 to sing a song, which the record company then turns into unnamed profits, in yet another kind of criminal scheme. This all ends up benefiting Capital, in O Brother symbolized by biscuit magnate and corrupt governor Pappy O’Daniel, who hands out patronage and represents Politics As Usual.

So there is plenty of money flowing through the narrative of O Brother, and all of it is achieved through ill-gotten gain. Money flutters through the air around George Nelson’s car, gotten as easily as walking into a bank and taking it, lost as easily as running into a crooked Bible salesman. Everything is a con, Ulysses is a fake (as opposed to his “bona fide” romantic rival), everyone is trying to make a dishonest buck. God is a racket, music is a racket, even sex is used as a trick to turn a man in for the bounty on his head. The “real people” of O Brother, the farmers and clerks and store customers, the churchgoers and voters, are seen by all the main characters as rubes, sheep and marks.

(Money is not the only thing that flutters through the frame in O Brother. A number of butterflies also happen by, usually in scenes associated with Delmar. I take this to mean that money, as it is in Lebowski, is an abstract commodity that happens by by sheer chance, or else that Delmar is like a butterfly.)

(And then there are the cows. The Coens go to a lot of trouble and expense to mistreat cows in one scene [“I hate cows!” shouts George Nelson, apropos of nothing], and then place a cow on top of a building at the climax as proof of the Magic Negro’s prophecy. I’m not sure what the cows are all about.)

There’s a moment in Act I when Ulysses and his pals go into the recording studio to sing “Man of Constant Sorrow,” a stunning piece of music direction all by itself, but George Clooney’s doing something interesting in the scene. As Tommy plays his guitar and Delmar and Pete sincerely belt out their harmonies, Ulysses looks, of all things, worried. This always puzzled me until I realized that he’s worried about getting caught in yet another criminal activity — it doesn’t seem possible that “singing into a can” could be seen as a legitimate way to make a living.

(The notion of “artist as outlaw” is one that the Coens share with their fellow Minnesotan Bob Dylan [who provides The Dude’s theme song in Lebowski], a connection I will explore more in my thoughts on The Man Who Wasn’t There.)

(But while I’m here, of course there is a more explicit Dylan reference in O Brother with the Coens’ use of “old-timey music,” which was enjoying its first revival in the Depression-era South, and then had a second revival in the late fifties in the North. Bob Dylan recorded the song that Ulysses sings, “Man of Constant Sorrow,” on his first LP.)

(Wash Hogwallop refers to the O Brother‘s economy by saying “They got this Depression on,” a line which has always sounded telling to me. Wash doesn’t see the Depression as the result of any confluence of economic events, he sees it as a a deliberate choice made by powerful people in faraway places, as though one would throw a Depression the way one would throw a garden party, as though it was a deliberate trick played on the poor, uneducated people of the South. Which I’m sure is how it felt.)

MUSIC: Music, we find, transcends the criminal world in O Brother, and is the thing that lifts the narrative from the commercial to the spiritual. As in most Coen movies, there are two major strands of music at war with each other — in this case, “black” music (blues and spirituals) and “white” music (folk and gospel). Instead of symbolizing the conflicts of the main characters as it does in most Coen movies, music here becomes subject matter itself. O Brother, in the course of its Three-Stooges narrative, chronicles a moment in American musical history where black music and white music fused, through the secular miracle of mass communications. Radio in the ’30s was like MTV in the ’80s — it brought all kinds of music into all kinds of worlds that had never heard it before, and musical cross-pollination in O Brother almost single-handedly transforms The Old South into The New South.

(Sam Phillips said in the ’50s that if he could find a white singer with the negro sound and the negro feel, he could revolutionize music. O Brother turns this formulation on its head, having its trio of white singers [who actually are seen in blackface for one sequence] be confused for black singers singing white music — a notion that shocks and enrages the racists of The Old South but delights the enlightened souls of The New South.)

CRIME AND PUNISHMENT: Surprisingly, O Brother presents the Coens’ darkest view yet of law enforcement. Police are absent in Blood Simple, comic bunglers in Raising Arizona, corrupt in Miller’s Crossing and menacing in Barton Fink, but O Brother goes so far as to paint them as literally evil, and the sheriff in charge of tracking Ulysses is no less than the Devil himself.

Thismakes tracking the spiritual signifiers of O Brother easy as pie. If Sheriff Cooley is the Devil and damnation, and is symbolized by fire, then God and salvation must be symbolized by water, and water symbols flow through O Brother like, well, I’d have to say like water I guess. The churchgoers in the forest walk down to the river, where their sins are washed away, the sirens pretend salvation while washing their clothes, Pappy O’Daniel, selling his biscuits on the radio, reminds his pious listeners to use “cool, clear water” in their recipes, a flood comes to save Ulysses and his pals, and even Pete’s cousin, who frees them from their chains, is named “Wash.”

(Then there is the moment where Sheriff Cooley almost lynches Pete by torchlight during a thunderstorm, and even makes a reference to the “sweet summer rain,” the Devil, we might say, quoting scripture to suit his purpose.)

The flood at the end of O Brother is caused by the building of a hydroelectric dam, the dam that’s going to bring enlightenment to the South. Which would make Franklin Roosevelt God, I guess, but it’s worth noting that George Nelson, in his final appearance, rejoices that it is electricity generated by this dam that’s going to shoot through his body and make him “go off like a Roman candle.”

(Radio is a force explicitly linked to God in O Brother — the soul-saving music goes out on it, Pappy O’Daniel depends on it for his campaign, and, at the climax, when Ulysses tells Cooley that the governor himself has pardoned him, on the radio, Cooley’s icy reply is “Well we ain’t got a radio.”)

MAGIC: There is a higher percentage of supernatural occurrences in O Brother than usual, or so it seems. Pete gets turned into a toad, but then it turns out not, the Devil buys Tommy’s soul, or maybe not, God saves Ulysses, or maybe that’s just the federal government. There is a balancing act going on all through the movie, every time something mysterious happens another explanation soon comes along to render it mundane. Magic is mostly cleansed from the narrative, but doubts still linger — in the final shot, the Magic Negro who advises Ulysses in Act I is seen still pushing his handcar across the railroad tracks of the New South.

“Everybody’s lookin’ for answers” in O Brother — some turn to racism, some turn to crime, some turn to sex, some turn to old-time religion, some turn to political reform. Penny’s daughters turn to her. The only answer that seems to be “right” is music, which seems to be able to heal all wounds and knit together a sundered society.

THE MELTING POT: Ulysses and his wife, Dan Teague and Pappy O’Daniel are all Irish-American. I don’t know where Delmar is from, and as for the Hogwallops, well, your guess is as good as mine. (Dan Teague, I’m guessing, is a reference to “McTeague,” the protagonist of Eric von Stroheim’s Greed. Other characters seem to be French-American, such as the Radio Station Man, and then there are the Afrian-Americans, largely unnamed (except for Tommy Johnson, the Robert Johnson stand-in) who make up a kind of Greek chorus.

The movie starts with the image of the chain gang singing a spiritual and ends with the image of a photograph of a rebel soldier being washed away in a technologically-induced flood. There are centuries of history in those two images, tracing the history of the south from slavery, the Civil War, through Reconstruction (which gave birth to the KKK), widespread poverty, the Depression and the Tennessee Valley Authority, which, as Ulysses notes, created a New South, literally washing away centuries of backward living, superstition and corruption (I remember visiting relatives in the South in the 1960s, and there were still plenty of people who were the first in their families histories to own telephones). Which is all very interesting, but one must note, what does that have to do with us?

I think O Brother, in a way, is about the internet. In the same way that radio (and then television) changed the way America saw itself, the internet is doing the same thing to the world. The language that Ulysses uses to describe the New South (“They’re going to run everyone a wire, hook ’em up to a grid”) could be applied with greater accuracy to our global situation today. And, without a doubt, we find ourselves in the middle of another cultural cross-pollination, which, according to the philosophy of O Brother, will save us from ourselves.

Following this metaphor would mean, of course, that America in AD 2000 was a nation of racist, intolerant, superstitious, backward-thinking yahoos. Oh, wait.

One nice thing about the generosity of O Brother is that it is not absolute. Pappy O’Daniel is, without a doubt, a corrupt, cynical politician, and is still very much in charge at the end of the movie. We like him better than we like Horace Stokes because Stokes is a blatant racist and O’Daniel endorses mixed-race music, but even in Ulysses’s moment of redemption there is still a threat behind O’Daniel’s endorsement — O’Daniel will pardon Ulysses only if he promises to go straight, which Ulysses promptly does. But, given the moral universe presented in the movie up to that point, it’s hard to imagine Ulysses being very happy working a straight job.

ECHOES: O Brother features the second of (to date) three scenes in Coen Bros movies where escaped fugitives have peculiar conversations with clerks in roadside establishments.

Another long, awkward elevator ride?

Perhaps, but man, dig that crazy sound.

Karlheinz and Ike, two great 20th-century composers, rest in peace.

Crass commercialism

You’ve seen him write about movies, maybe you’ve even seen his movies, now you can own his movie memorabilia!

It’s occurred to this writer that his children are not, in fact, going to educate themselves, and all the toys he bought as a carefree, spendthrift, childless movie nut would now be better turned into cold hard cash. Starting with this handsome Godzilla toy from the ill-regarded 1998 release. Matthew Broderick not included.

If you are interested in obtaining this crucial piece of pop-culture history, or if you just want to read this author’s pithy description of same, here’s your chance.

And here‘s another!

Star Wars: Episode VII — the treatment, part 1

My son Sam (6), if I haven’t mentioned it before, loves Star Wars. He’s watched all six of the movies numerous times (Episode III is his favorite, followed by Episode II), owns over a hundred action figures (many of them hand-me-downs from Dad) draws pictures of the characters every chance he gets, and has recently completed a movie (which Dad is now editing — it has, I’m afraid, many longueurs). It was inevitable that he would turn to writing scenarios for imaginary Star Wars stories. I don’t have the heart to tell him that he could probably make good money at doing this work.

Tonight’s bedtime conversation:

SAM: Dad?

DAD: Yes?

SAM: You know what would be better?

DAD: What would be better?

SAM: If, at the end of Episode IV (A New Hope, or Star Wars, to peopleover 30 years old), if instead of Luke Skywalker shooting a photon torpedo into the Death Star? If instead he shot down a TIE Fighter and the TIE Fighter crashed into the exhaust port instead and set off the chain reaction.

DAD: Yes. You are correct, that would be better.

SAM: And in Episode VI (that is, Return of the Jedi)?

DAD: Yes?

SAM: Well, actually, Episode VI is good the way it is.

DAD: You think so?

SAM: Yeah. Except —

DAD: Except?

SAM: It would be cool if, instead of the rebels blowing up the reactor in the middle of the Second Death Star? If, like a million Star Destroyers and Super Star Destroyers crashed into the Second Death Star.

I cannot tell you how much these little conversations make my heart burst with pride.

As a service to my loyal readers, allow me to offer a version of this story with proper spelling, punctuation, and a few small textual notes:

1)”As the second Death Star explodes, the Dark Trooper arrives in a TIE Fighter at a Battleship, with lots of Troopers. There is a menace named Darth Black.”

NOTES:

The “Dark Trooper” is a reference to the bad guy of the unplayably outdated video game Star Wars: Dark Forces. Sam has never played this video game, but he does have an action figure of the Dark Trooper, who looks like this:

By “Battleship” he is referring to a Star Destroyer. “Darth Black” is not a typo but a new character, a heretofore uncelebrated Sith lord.

Sam completed the first page of this story after school one day and was hugely excited by it, as was I.

SAM, pen in hand: What should I write next?

DAD: Well, what happens next? It’s the end of Episode VI, the second Death Star has just exploded, that’s a great beginning. Now I see you’ve got a Dark Trooper who survived the explosion. That’s also a great idea — the Empire has just collapsed, the Emperor is dead, but there are all these millions of soldiers who worked for him — what are they going to do? What are their loyalties? Are they being hunted by rebels, do they form their own army, what do they do? And here I see you’ve got a new character, this Darth Black — what does he want? What makes him a menace? And who’s saying he’s a menace? A menace to whom?

SAM, visibly distressed: Just tell me what to write…

And then, moments later, he was off again, no help needed from me. And, as you will see, he utterly ignored every helpful suggestion I made, a decision that makes my heart sing. (I have since learned that, when he wrote the first page, he didn’t actually know the meaning of the word “menace.”)

2) “As, waiting, Darth Black calls the Imperial Spy. All troopers are in position, and as the Imperial Spy sets up his troopers, a figure arrives in the distance.”

As the proud father, I note that Sam has already mastered the technique of always pitching a story in the present tense. I also note, with some interest, that he begins two pages in a row with the word “as.”

The geography of these scenes, however, is confusing, and doesn’t get better. I think the Imperial Spy and Darth Black are on two different space ships, but I could be wrong.

The “Imperial Spy,” for those who don’t speak Star Wars, is this guy:

A minor character from Episode IV, without any proper dialogue, he has nonetheless captured Sam’s imagination. You never know what’s going to do it I guess.

3) “It was Qui-Gon Jin. The Imperial Spy saw his lightsaber was red. He went up to the Imperial Spy. He [stood] there. The Imperial Spy called Darth Black.”

Qui-Gon Jin, of course, died at the end of Episode I. His appearance here, therefore, counts as a major revelation. Close readers will note the color of his lightsaber — only Sith’s lightsabers are red.

At this point, I had to ask what Darth Black looked like. Sam replied that Darth Black was the brother of Darth Maul, had the same horns growing out of his head, and had black skin. I imagine him having the same kind of wild face-decoration as Darth Maul (that is, I think it’s a decoration) but in a kind of black-on-black pattern instead of red-on-black, which, I’ve got to admit, is a whole lot more cool.

4) “Suddenly Rebels [a]re surrounding the two figures [by which I think he means Qui-Gon and the Imperial Spy]. They [take] out their guns. Suddenly, Qui-Gon jump[s] up in the air and kill[s] all the rebels. He [is] a good fighter. He [Darth Black] [is] impressed.”

I have to say, for a six-year-old, having the red lightsaber pay off with a stunning plot twist of Qui-Gon turning out to be evil, is truly inspired.

5) “Darth Black heard about the Jedi [that is, had heard of Qui-Gon Jin, and, by extension, knows that he is supposed to be dead]. He calls him over [calls who, and from where, is unclear]. The Imperial Spy got in his ship. The Jedi [Qui-Gon] snuck in after him. He flew to the battleship [the same battleship as the Dark Trooper?]. He got out. The Jedi snuck out too. He [the Jedi, Qui-Gon] explored. Someone saw him. He [the someone? The Imperial Spy?] [brought] him to Darth Black.”

6)”Darth Black ask[s] where they found him [that is, Qui-Gon]. ‘He was walking around’ [replies someone]. ‘Maybe he [is] the bad Jedi I[‘ve] heard about’ [says Darth Black]. ‘What Jedi?’ [asks the someone]. The Imperial Spy walk[s] past. He [sees them talking] [that is, he saw Darth Black talking to the someone]. Suddenly a ship arrived in the distance.”

Again, I’m a little confused about who Darth Black is talking to and what role the Imperial Spy plays in all this, but this much is clear: Qui-Gon Jin is alive, and evil, and he’s looking to join the ranks of a Sith lord who has, somehow, survived the collapse of the Empire. If you’ve got a better idea for Episode VII, I want to hear it.

Movie Night With Urbaniak: Heaven’s Gate (part 1)

As

is an actor of delicate constitution who requires his beauty sleep, we were unable to watch all 219 minutes of Michael Cimino’s legendary cinematic disaster in one go — we left off at the intermission and will pick it up again soon (the promise of a DVD screener of There Will Be Blood is the carrot, watching Heaven’s Gate is the stick in this relationship).

I rushed right out to see Heaven’s Gate when it opened in 1980 in a shortened version. I had seen The Deer Hunter several times in the theater and enjoyed it quite a bit and I was anxious to see what Cimino would do with a western. I had heard all the stories about his extravagant profligacy on the set (the budget was, reportedly, over $40 million) and, being who I was, I was pulling for the director. I had heard about the disastrous screening of the long version, I had read all the terrible, terrible reviews, I knew no one was going to go see this movie, yet I was there, first screening, opening day, hoping against hope that, somehow, everyone was wrong and some kind of unique, misunderstood masterpiece awaited me.

Well, that didn’t happen, but I still couldn’t quite bring myself to hate the movie. Being a mere wisp of a 19-year-old, I did not possess the relative understanding of story structure I do now, so I couldn’t quite put my finger on why the movie didn’t work. But I could not deny that much of it was beautifully rendered, and there was something weird and mysterious about its insistence on having nothing happen for long, long stretches of movie. And that was the short version.

Now that I’m a big-deal Hollywood hotshot, it’s easy to identify the movie’s problems, although it might not have seemed that way in 1979. Basically, there is a HUGE amount of atmosphere

and very little plot.At the two-hour mark, I found I could count the total number of plot-points covered on the fingers of one hand. This is, alas, not an exaggeration.

PLOT POINT 1: Kris Kristofferson graduates from Harvard in 1870. The statement of this fact takes up an astounding 23 minutes of screen time.

PLOT POINT 2: Twenty years later, Kris is a sheriff (I think — it’s unclear and the sound mix on the DVD is perhaps the worst I’ve ever heard — ambient background thunders in the speakers while actors in the foreground murmur beyond audibility) in Wyoming, where Big Doings are going down: corporate ranchers are preparing to go to war with poor immigrant farmers. The establishment of this plot point takes us another twenty minutes.

PLOT POINT 3: Kris is in love with a French prostitute. Getting this idea across takes, I’m not kidding, 30 minutes of screen time.

PLOT POINT 4: The poor immigrants may be poor, but they sure know how to have fun. This accounts for another 30 minutes, as we watch cheerful immigrants pose for pictures, juggle, roller skate, dance, have sex, play music, sing, stage cockfights, fight and swear and grin. As Urbaniak noted, it’s like the party scene in steerage in Titanic, but expanded a half-hour.

PLOT POINT 5: Chris Walken, a hatchet-man for the corporate ranchers, is also in love with the French prostitute, and intends to sue for her hand. This accounts for the final 20 minutes of screen time before intermission.

And that’s it. Honestly.

Now compare this to, say, the plot of Raising Arizona: The protagonist robs convenience stores, goes to prison at least three times, meets and falls in love with the police officer in charge of booking him, rehabilitates himself, asks her to marry him, moves in with her, settles down, tries and fails to start a family all before the title sequence begins. If Michael Cimino had directed Raising Arizona he would have spent a half hour just examining the daily activities of the convenience-store clerk.

It’s hard to watch this movie and not feel for the studio executives in 1980 — faced with this extraordinarily slow, almost-plotless story, it’s impossible not to think “well, they could easily trim this down and have a taut little western.” And yet, if you cut out all the impressive atmosphere (and a good deal of the atmosphere is truly impressive) you would not have a “taut little western,” you would have a slack, underplotted little western. Now, there was, once upon a time, room for movies that place atmosphere over plot, but not to the ridiculous extremes taken by Heaven’s Gate. I mean, Jean-Luc Godard is Steven Spielberg compared to Michael Cimino in this regard.

And yet, for some strange reason, the movie is not “boring,” exactly. It sustains interest, partly through its dense atmosphere, partly through its peculiarity — it’s novel, and even pleasurable in a certain way, to see a big-budget movie utterly unconcerned with forward momentum. Urbaniak says that it’s interesting without being dramatic, a sentiment I echo, and add only that the scenario is dramatic it’s just very poorly structured dramatically. You’ve got a bunch of evil ranchers who are hiring an army of gunmen to wipe out a community of immigrants, that’s an excellent start for a drama. But that plot point is not announced until minute 43, and nothing is done about that struggle for another hour of screen time. Kris Kristofferson hears about the rancher’s nefarious plan and heads off to the immigrant community to, um, to do, um, well, we don’t know what exactly he plans to do, but we know he doesn’t like the ranchers so we assume he is on the side of the immigrants. So he goes pouncing off to the immigrant community and immediately spends thirty minutes horsing around with his girlfriend.

The cast is large and capable and includes many actors who went on to become big stars, so that’s always fun. Most of the acting is decent enough (there is one scene where Kris Kristofferson and John Hurt square off in a billiard room, having a “barely audible growl-off”)

and some is quite excellent. Urbaniak adores Chris Walken in this movie, an appreciation I can’t quite share — his presence seems too modern, too off-center and not of-the-time. But I bow to his superior judgment in this regard. Sam Waterston, on the other hand, is just dreadful as the main Evil Ranch Guy. He struts, preens, glares and flares his nostrils as his forces gather around him, all to remind us that this guy is Evil. It seems to me that once the screenplay identifies you as the Evil Guy, the best thing you can do is As Little As Possible.

The sound mix is, as I’ve noted, abysmal, and the transfer is substandard — probably because they had to cram a four-hour movie onto a single DVD. The production design is sumptuous and absurdly detailed, without ever clearly showing where the $40 million went. The score is an embarrassment, it sounds exactly like the first idea pitched at the initial post-production meeting.

Oh, and the haircuts — why can’t they ever get the haircuts right? All the supporting players look appropriately 19th century, but every time a lead actor strolls on, it’s 1979 again.

Coen Bros: The Big Lebowski

“Your revolution is over! The bums lost!” images swiped from the excellent Coen resource “You Know, For Kids!”.

NOTE: I have gone over (not to be confused with “micturated upon”) the deeper meanings of The Big Lebowski once before — you may read my previous analysis here.

THE LITTLE GUY: The Dude is unique in the Coen universe in being a protagonist who is perfectly happy with his social standing. He does not seek money, betterment, achievement, a child, a mate, clean clothes or, really, anything besides a state of blissful intoxication. Anything he does he does because someone else is forcing him to do it. As the Stranger describes him, “he’s the laziest man in Los Angeles County, which would place him high in the running for laziest worldwide.” He’s not particularly interested in saving the kidnapped girl, recovering the stolen fortune or even defending himself from hoodlums. Even his desire to reclaim his soiled rug is something that his bellicose friend Walter puts him up to — if it were up to The Dude, his peed-on rug would be worth it just for the story to tell his bowling buddies.

(It’s also worth noting that, for all the time The Dude spends hanging out in a bowling alley, listening to bowling games of the past and fantasizing about bowling scenarios, we never actually see him bowl.)

Many dismiss, or praise, The Big Lebowski as a “shaggy dog story.” These are people with not enough time on their hands. Lebowski is a movie positively overstuffed with meanings, far too many meanings to be gleaned from a single viewing.

WHERE’S THE MONEY, LEBOWSKI? Let’s start with Lebowski’s brilliance as a detective story. Lebowski presents us with a Big Sleep-style mystery: What Happened To The Kidnapped Heiress? But the kidnapping plot, we eventually find, is a gigantic red herring. The real mystery in The Big Lebowski is Where’s The Money? This is not anidle plot-point, it is a key subtext to understanding the importance of the movie. The kidnapped girl is a worthless idiot of importance to no one, but the money, ah, the money, as Mose in Hudsucker would say, “drives that ol’ global economy and keeps big Daddy Earth a-spinnin’ on ‘roun’.” The Big Lebowski is a social critique disguised as a mystery disguised as a stoner comedy.

The key to understanding the social dynamics of The Big Lebowski is to always follow the money. So where is “the money” in The Big Lebowski? (“Where’s the money, Lebowski?” is, in fact, the movie’s first line of dialogue.) The Dude doesn’t have it — he lives in a crappy Venice bungalow and is late on his rent. His friend Walter has his own business, but doesn’t have any appreciable amount of it. Jeffrey Lebowski, despite appearances, doesn’t have it, and his wife Bunny obviously doesn’t have it. The Nihilists don’t have it and neither does Larry Sellers, even though Walter is positive he has it.

The joke is, of course, that no one has it — “the money” belonged to the first Mrs. Lebowski, who is long dead. We don’t know how Mrs. Lebowski got her money — “Capital,” the source of “the money” in The Big Lebowski, is nebulous and taken for granted. “The Money” is like “The Gold” in Eric Von Stroheim’s Greed — it’s not something to be earned, it’s almost a natural resource, something that’s just sitting around waiting for someone to figure out how to get it.

Who has any money in The Big Lebowski? Maud Lebowski, Jeffrey’s daughter, the aggressively “feminist” artist, has some money, but even that is not hers, it’s her mother’s. She hasn’t earned it and seems to be frittering it away on ugly art and an inane lifestyle (the other artist presented in Lebowski is The Dude’s landlord, with his stupefying Greek Modern Dance routine — art doesn’t seem to count for much in the Lebowski universe). The only other wealthy personage in Lebowski is Jackie Treehorn, the pornographer. So: in the world of The Big Lebowski, “Money” is represented by an embezzler, an heir and a pornographer — as harsh a critique of American capitalism as I’ve ever heard.

Everyone else is barely scraping by or actively losing money hand over fist. The indignities heaped upon The Dude in this narrative are great: his house is repeatedly broken into (“Hey, Man, this is a private residence” he lazily chides a trio of armed thugs), his possessions are smashed until nothing is left of them, his car is shot at, crashed, stolen, crashed again, peed in, bashed and finally set fire to. He is punched unconscious, drugged and hit with a coffee mug. The Rich in Lebowski get richer by soaking the Poor, and every transaction between social unequals is a heartbeat away from physical violence. Even Maud, who only wants her rug back, can’t resist using force upon The Dude in order to get what she wants.

(The other thing Maud wants, of course, is to conceive a child. This is a succinct reversal of the argument of Raising Arizona. In the earlier movie, Ed reasoned that the Arizonas [The Rich] deserved to lose a child so that she [The Poor] could have one. In Lebowski, Maud [The Rich] assumes that it is her right to use The Dude [The Poor] as a method to get her own child — in both movies, children are merely another expression of capital [or, as the Dude complains about pornographer Jackie Treehorn, “he treats objects as people, man.”)

THIS AGGRESSION WILL NOT STAND: “Aggression” is a big word in Lebowski. The Dude is, of course, the least aggressive person in the story, yet he invites aggression at every turn, from his friends, his bowling rivals, his various contacts in the mystery. The parallel is drawn to the Gulf War, and if there is a coherent critique of the Gulf War to be found in Lebowski (and I’m not sure there is) it could be better applied to our present situation in Iraq: in Lebowski, aggression is met with violent retribution — but it always falls on the wrong person. Jackie Treehorn wants his money, but his goons beat up the wrong Lebowski. The Dude’s rug is peed on, so he demands retribution from a complete stranger. Jeffrey Lebowski sends The Dude to identify the kidnappers as Jackie Treehorn’s thugs (he won’t take responsibility for The Dude’s rug, but insists that The Dude take responsibility for his missing wife), but finds they are completely different people (and gets his car shot up for his trouble). The Nihilists demand a ransom for Bunny, but cut off the toes of one of their own to prove their seriousness. Walter exacts violent retribution on Little Larry Sellers, but ends up bashing the car of a complete stranger.

This, I think, is the meaning of poor Donny’s death. In times of war, wealthy, powerful men make up their minds to be aggressive (Saddam against Kuwait, Bush against Saddam), but the people affected are always the poor and powerless, people who die without ever understanding what the true cause of the aggression was. In the case of the Gulf War, it was the Iraqi soldiers and civilians who sided with the US, only to be abandoned, in the case of Lebowski it’s poor Donny, who’s salient quality is that he never knows what the hell is going on and who dies, absurdly, of a heart attack during an attack by the Nihilists.

(This is also, I think why Walter compares Donny’s death to the troops lost in Vietnam, although Walter, to be fair, tends to compare everything to Vietnam. He compares Bunny’s kidnapping to Vietnam, he finds service in diners lacking due to his experiences in Vietnam. The Dude chides Walter for this habit, but Walter, I think, is on to something. Bunny’s “kidnapping” can be compared to Vietnam, insofar as it’s a mysterious act of aggression perpetrated by a wealthy man scheming to steal a ton of money and make a poor man pay for it.)

CRIME AND PUNISHMENT: The Big Lebowski presents the widest view of law enforcement in the Coen canon. While not as warm or good as the police in Fargo, the police in Lebowski could at least be described as cheerfully unhelpful. They laugh at The Dude’s problems for the most part, but they don’t actively seek to harm him and they are not shown to be in direct employ of the forces of evil.

That’s LA’s cops, obviously. Malibu is a different story — the sheriff in Malibu is a reactionary hothead, the fascist boot protecting the rights of a pornographer.

Jeffrey Lebowski lives, of course, in Pasadena — but we manage to get in and out of his community without a run-in with the police.

THE MELTING POT: Race and national origin always plays a significant role in the Coens movies, and Lebowski emphasizes this more than ever. Oddly, all the main characters are Polish-American. Donny is Greek, Brandt I’m going to say is a WASP, Bunny is Swedish, the Nihilists are German (as is the administrator for The Dude’s bowling league), Jesus Quintana is Hispanic (and a pedarast), the cops are racially mixed (as are Jackie Treehorn’s goons, and the casts of his porn movies), Maud’s friends are European (one might say “Eurotrash”), the poor owner of the Ferrari is Hispanic, the detective shadowing The Dude is Italian (as is Maud’s chauffeur, although Jeffrey Lebowski’s chauffeur is French). Maud’s doctor is Iranian, and The Dude gets thrown out of a cab driven by an African-American man who likes the Eagles. The only Jew visible is, of course, Walter, who isn’t really Jewish. I wonder if it means anything that the only character identified as Jewish (that is, Walter’s ex-wife) is out of town for the duration of the narrative?

What is the point of this rainbow coalition of characters? Is it merely a comment on the diversity of LA, or is the city in Lebowski meant to symbolize something bigger, the whole of the US, or even the whole of the world? Is Jesus’s florid aggression toward our heroes meant to be an analogue to Saddam’s aggression against Kuwait?

PANCAKES: Nihilist Uli Kunkel favors pancakes for a meal, just as Gaere did in Fargo. I can see no significance here except that “pancake” is a funny word. In The Ladykillers the protagonist favors waffles, which I think explains that movie’s miserable death at the box office.

Hulk To-Do List

Found this post-it note, as is, stuck to my refrigerator door one morning. Needless to say, between the color of the paper and the items listed, I could only come to one conclusion — The Incredible Hulk had left his to-do list in my kitchen for some reason.

(Turns out SMASH is an acronym for a Santa Monica school organization my wife needed to call — but I like my version better.)

UPDATE:

Coen Bros: Fargo

Fargo is a remake of Blood Simple, insofar as they are both crime dramas without protagonists. Oh, one remembers Fargo ashaving a protagonist, but it doesn’t really. What it has is a likable main character, which is a different thing from a protagonist, and is something that Blood Simple doesn’t really have. Marge, the pregnant sheriff, is but one-third of the three-pronged narrative of Fargo, and does not show up until the beginning of Act II. Up until that point, it appears that the protagonist of Fargo is Jerry Lundergaard, the hapless, bitterly frustrated car salesman who plots to have his wife kidnapped. That would, in fact, make Marge the antagonist, the Javert to Jerry’s Jean Valjean. But, as the narrative develops, we find that Fargo is balanced between Jerry, Marge and Carl Showalter, the fuming, delusional, small-time crook whom Jerry hires to kidnap his wife.