The Great Debates

ANNOUNCER.

Candidate number one, your opening statement.

C1.

Apples are better than oranges.

A.

Candidate number two, your opening statement.

C2.

Oranges are better than apples.

A.

Candidate number one, your rebuttal.

C1.

Apples are American. We put them in pies. And we call it Apple Pie. As in Mom and Apple Pie. We do not put oranges in pies. There is no such thing as Orange Pie. No one will ever say “Mom and Orange Pie”. Or even “Mom and Oranges”. No one will ever mention oranges in the context of America. No one will ever say “It’s as American as fresh squeezed orange juice.” Apples are better than oranges.

A.

Candidate number two, your rebuttal.

C2.

Apples, as candidate number one knows all too well, are covered with a red or green skin which can cut into the gums when one happens to bite into an apple. This hurts. It hurts me, and it hurts you, and it hurts America. Oranges come safely wrapped in an Orange Peel, which one removes easily and then one can eat the orange in individual sections. Or one could give half of the segments to charity. No one would ever give half an apple to charity. Only an orange. Only an orange represents the democratic ideal.

A.

Candidate number one?

C1.

I would like to ask candidate number two a question: have you ever peeled an orange when you have a hangnail? Hm? Hurts, don’t it. Hurts. Hurts like the Dickens. Why? Because, as candidate number two knows all too well, Oranges are Filled With Acid. It says so right on the label. And yet some Americans, I won’t name them, give them to their children. To eat at lunch. They feed their children GLASSES OF ACID for breakfast. This is not American. Nowhere in the constitution does it say “Oh yeah, and go ahead and feed ACID TO YOUR CHILDREN.

A.

Candidate number two?

C2.

I promised the American people that I would never stoop to negative campaigning. And yet candidate number one leaves me no choice. It is a known fact that apples cause cancer. It is also a known fact that apples have shady financial histories and ties to organized crime. It is also a known fact that apples were brought here by creatures from another planet for the purposes of enslaving the human race. I am not going to address these points. I am simply going to hold up this piece of paper. This piece of paper shows Candidate number one engaging in kiddie porn while eating an apple.

A.

Candidate number one?

C1.

Well. I am embarrassed. Yes I eat apples. Yes I have had sex with children on videotape for money while eating an apple. Does the American public care about that? I say that they don’t. And let me just say one thing: Apples come in two colors, “Apple Red” and “Apple Green”. Oranges come in only one color: orange. How’s that for simplemindedness? “What is it?” “An orange.” “What color is it?” “Orange.” My fellow Americans, God made the little green apples, just as he made the space creatures who brought them to us. God did not make oranges and candidate number two knows it.

A.

Candidate number two, your closing statement.

C2.

I believe in the United States of America. And you can call it hope, or faith, or blind devotion, or paranoid schizophrenia, but when my voices tell me to eat an orange, I do it. I do it. I don’t “doubt” them. I don’t “question” them. And you should not question me. You should merely vote for me and then do my bidding. And that is what America is to me.

A.

Candidate number one, your closing statement.

C1.

Let me just say this: I am so incredibly high right now.

A.

Thank you candidate number one and candidate number two. Please join us next time on “The Great Debates”.

Sweet and Lowdown

Emmett Ray and Rusty Venture compare notes. Pun intended.

If The Venture Bros were a musical biopic, it would be Woody Allen’s Sweet and Lowdown.

Emmett Ray (Sean Penn) is a brilliant guitar player, but he lives in the shadow of greatness, namely Django Reinhart. Living in this shadow has apparently cast a pall over Emmett’s entire life. (![]() urbaniak fans know that Rusty Venture himself is in the movie, in a very Rusty kind of role, The Guy With Few Lines Sitting Next To The Star. So Emmett spends the movie in the shadow of Django, and “Harry” [

urbaniak fans know that Rusty Venture himself is in the movie, in a very Rusty kind of role, The Guy With Few Lines Sitting Next To The Star. So Emmett spends the movie in the shadow of Django, and “Harry” [![]() urbaniak‘s character] spends the movie in the shadow of Emmett.)

urbaniak‘s character] spends the movie in the shadow of Emmett.)

Emmett’s problem, it seems, is that he keeps his feelings under tight control, and that has crippled his artistic muse.

(Robert Fripp tells a story where a critic takes him aside one day to inform him that he (Fripp) and Jimi Hendrix were the two greatest guitar players of their day, the difference between them being that Fripp had all the technique in the world but nothing to say, and Hendrix had no technique and everything in the world to say. Fripp, being who he is, and English besides, could only agree with the critic’s assessment.)

(And I own one CD by Hendrix and 85 by Fripp, which probably tells you everything you need to know about my aesthetic tastes.)

What does Emmett Ray want? Well, like Charles Foster Kane, he wants to be loved, but only on his own terms. A hugely talented artist with one of the most impoverished souls ever brought to the screen, he’s bought his own line; he routinely introduces himself as “Emmett Ray, the greatest guitar player in the world” (and occasionally adds, in shame, “except for this gypsy in France, Django Reinhart.”) Women, for Emmett, are an audience, so when he starts up (“falls in love with” is too generous a phrase) with mute Hattie (Samantha Morton) it seems like he’s found his perfect mate.

His life with Hattie brings his soul to the brink of awakening, and brings with it a certain amount of artistic and financial success. (Allen can’t quite bring himself to equate the two; instead, he brings success to Emmett Ray by having him, literally, fall into a pile of money.) Being the egotistical boor he is, Emmett assumes that he’s achieved the success all on his own and promptly leaves Hattie for Blanche (Uma Thurman), who is Hattie’s polar opposite. Hattie is poor, simple and mute, Blanche is society-born, pseudo-intellectual and won’t shut up.

Blanche is attracted to Emmett because he’s a lowlife and that makes him “real.” So it’s only a matter of time before she drops him for someone even more “real,” namely button-man Anthony LaPaglia. (The equation/comparison of artist and killer is explored more fully in the superior [and funnier] Bullets Over Broadway.)

What makes Emmett “real,” in spite of his shortcomings? He has three consuming passions in the movie: playing guitar, watching trains and shooting rats at the dump. Blanche tries to plumb the depths of these bizarre pastimes on an intellectual level, but neither Allen nor Emmett seem interested in them on that level. Emmett is simple enough to do what he does and not think about it, but he’s not simple enough (or generous enough) to entirely lose himself. He’s always got to show off, he’s always got to announce himself. He needs an audience or else nothing is worthwhile. The movie never shows him merely practicing, or doing anything by himself really. It seems he couldn’t imagine playing guitar for the sake of playing; it would have to be in front of people. There’s a climactic scene where a heartbroken Emmett (see below) tries to conjure up some choice licks to seduce Gretchen Mol, a dimwitted dance-hall girl, in a train yard; when he realizes she’s not listening, he disintegrates emotionally and destroys his guitar.

The tone of the movie occasionally veers from warm, detailed, straightforward behavioralism into broad silliness, which strikes me as odd and unnecessary. It seems as though Allen doesn’t trust his material enough to write Emmett’s story entirely seriously, or doesn’t trust his audience’s willingness to consider a subject as ethereal and complex as the artistic muse.

Another way of addressing this problem is to ask, Why is Emmett the way he is? The script doesn’t really say — it suggests that maybe Emmett had a bad childhood, grew up poor and without proper parenting, but that’s true of hundreds of artists more generous of spirit than Emmett — why is Emmett so stunted and unavailable? The movie leaves the question unanswered. He is the way he is. (Allen has never been shy of making plentiful use of the lazy screenwriter’s friend, narration, and uses it to connect the dots and fill in the blanks here as well, both in the witty “real life” narrators like Nat Hentoff and Allen himself and in Uma Thurman’s Blanche, all of whom attempt to allow the audience under Emmett’s skin, to no avail.)

The acting in general is very good, but Sean Penn is extraordinary here. There are a number of scenes where he is called upon to be a genuine human being and we can see the war in his eyes between his desire to feel and his inability to do so. He’s not just a jerk, he’s a jerk who has salvation easily within his reach at every turn and yet chooses to shun it.

There’s a scene toward the end where Emmett goes back home to find Hattie and ask her forgiveness. In the movie’s best moment in both the acting and screenwriting departments, Sean Penn grudgingly asks Hattie if she wants to come back to him and she, unable to speak, hands him a note. He reads it, and after a pause, asks “…Happily?”

Strangely, given the subject matter (an artist unwilling to engage with his feelings, and thus failing), this was Woody Allen’s last really good movie for a long, long time.

Venture Bros: Viva los Muertos!

I don’t think it’s too much of an exaggeration to say that “Viva los Muertos!” is the reason that television was invented.

No joke: just the other day I was asking myself if there is an upper limit to the themes and issues that an episode of Venture Bros could address.

Question answered.

The themes this week are among the grandest imaginable: war, authoritarian control, the one-ness of existence, the border of life and death and the nature of humanity.

We start in the middle of a war film. The Monarch is sending his henchmen into battle. We are behind the orange-tinted goggles of one of them. The Monarch, unlike last episode, is not there for the invasion; no, this battle he’s sitting out, content for now to send his men to their deaths, as any good general does in any war.

It’s present day, but the language of the henchmen comes from older war films. The trench recalls World War I and the reference to “taking this hill” recalls Paths of Glory, Kubrick’s study of military cruelty, where primping generals sip tea in chateaus while sending their men to die for no reason at all. It makes me wonder what the Monarch’s goal for this incursion was, why he’s not participating today, what he has to do that’s more important.

As in Paths, the incursion is a failure and our POV henchman is quickly dispatched by Brock, only to be brought back to life by Dr. Venture, in the manner of Frankenstein’s Creature, just in time for that landmark film’s 75th anniversary. “The Holy Grail of super-science,” Rusty crows, life from death. Death, science wishes to show, is not the undiscovered country, the land from which no traveler returns, but just another tool for maximizing profit. The fact that Venturestein can hardly be called human atthis point seems to be beside the point — Dr. Venture has re-animated dead flesh and stands to profit greatly from it.

Like Frankenstein’s Creature, “Venturestein” identifies Dr. Venture as his father, a notion Dr. Venture quickly quashes. “I get enough of that noise from these two,” he says, gesturing to Hank and Dean. This brings up an important and vital aspect of Dr. Venture’s parental instincts: why does he keep bringing Hank and Dean back to life, since he has no interest in being a father? “Dean, as of right now Hank is better than you,” he snaps at his children, as good an example of bad parenting as we are likely to see on television this season. And yet we will see later in the episode that parenting isn’t always just a nurturing instinct born of love, it can also spring from a desire to mold and warp, to control and shape an unformed mind. Dr. Venture puts Venturestein in Hank’s bed to teach him, what else, the relative value of a life of legalized slavery (which explains his afro head and the beat about Hank and Dean trying to find “Africa-America” on the globe), or, as Venturestein succinctly puts it, “Prostitution!”

Now then: The Groovy Gang.

The average writer says “Hey, let’s have the Mystery Gang meet up with the Venture Bros. It’s a natural. And they can be middle-aged and failed, driving around in a beat-up van solving mysteries.” But it takes the genius of the creators of Venture Bros to take the mystery gang and invert them from optimistic, youthful children of the 60s (don’t forget, Fred, Daphne, Velma, Shaggy and Scooby were, literally, on their way to the Woodstock festival when they were waylaid by their first mystery) to a pack of the darkest, most repugnant criminals of ’68-’78, namely Ted Bundy, Patty Hearst, Valerie Solanas and David Berkowitz (and his talking dog Harvey). And so “Ted,” the leader, becomes a vicious, controlling thug, good looking and charming on the outside but murderous and brutal on the turn of a dime, threatening to put Patty “back in her box” and regularly threatening “Sonny’s” life. (It’s hard to see why Val, whose real-life counterpart felt that her life was controlled by men in general and Andy Warhol in particular, would be part of this gang, except that she seems to see herself as some sort of protector/predator of victimized Patty.)

Ted pulls the van up to the Venture compound in a thunderous rainstorm (a rare use of “atmosphere” in the Venture world). “I smell a mystery!” he says, apropos of nothing. Or is it? Ted can’t know about Venturestein running amok inside the compound. What mystery is he referring to? And then we realize: Ted Bundy, and all intelligent, cold-blooded killers, fascinate us precisely for their investigations into the same mystery that Dr. Venture is “prostituting” inside the compound: the border between life and death. In a sense, Ted is always pursuing not just “a mystery” but the mystery — what happens to us when we die?

The serial killer cannot keep himself from his quest in the same way that Dr. Venture can’t keep himself from his own. One kills from insanity and the other brings men back to life from a different kind of insanity. The killer answers to a higher power (a point driven home by Sonny’s dog, growling at him about “The master’s orders”) while the scientist pretends to be that higher power to reverse the process. And so unholy Creator and equally unholy Destroyer are set on a collision course on the Venture compound on a dark and stormy day.

(There’s more than a little of George W. Bush in Ted as well. When asked for reasons for invading the Venture Compound, Ted invokes both God and the lack of gasoline as reasons enough. When Sonny questions further, he’s met with accusations of disloyalty and the barrel of a gun.)

Because Venture Bros episodes consistently teem with twinning and reflections, our B-story this week concerns a more serious version of Creator and Destroyer. Brock feels bad about killing Venturestein (twice) and crashes Dr. Orpheus’s shaman party (or “Dracula factory!” as Ted puts it, completing the “Universal Monster Movie 75th Anniversary reference” beat [and also bringing up vampirism, the other most-potent “life from death” myth of the 20th century]) . The shamans all drink wine made from the ego-destroying “Death Vine” (which reminds Brock a little too much of “a Jonestown thing,” yet another reminder of authortarian control, a bad father, run amok) and when Brock tells his story of killing the henchman, the oldest, most respected shaman tells a seemingly unrelated story of having sex with a dolphin.

Or is it unrelated? Sex, after all, is the opposite of murder, and the dolphin could be seen a purer, more instinctual level of existence. The dolpin, which science has shown is the intellectual equal (if not superior) of humanity, manages to live a free, toil-free life in spite of its intelligence. It sees no need to organize into complex societies, print money, go to war or enslave children (to name only the most radical of the offenses listed this week). The shaman’s story of the dolphin, in spite of its absurdity, is truly the opposite of Brock’s story of senseless, state-sanctioned murder.

Dr. Venture is a bad father, and so is Ted, and so is the unseen government constantly lurking in the background of the Venture world. Dr. Venture has finally achieved success; the army wants 144 of his Venturesteins to use as walking bombs; Rusty has no trouble taking the order, and assumes that Brock, the born killer, will simply “make some dead bodies” for him.

But Brock is changing; he’s questioning the limits and certitude of his powers, his “license to kill.” And so he “drinks the Kool-Aid,” as it were, with the shamans (who lose their lunches, as well as their egos, as they drink from the Death Vine) and has his hallucination involving that same dolphin spoken of earlier. The dolphin explains the importance of empathy and the oneness of existence to Brock (just as its darker twin, Groovy, commands Sonny to murder on the behalf of the mysterious “Master”). The hallucinatory dolphin is then, of course, murdered by a hallucinatory Hunter Gatherer, Brock’s own authority (and father-) figure. Hunter sets Brock straight on his nature and purpose in the world. We are here to kill, he insists, on the behalf of our masters, invoking another Kubrick war film, Full Metal Jacket. It’s enough to snap Brock out of his confusion and set him back on his path of righteous destruction.

Meanwhile, in another part of the compound, Sonny sees Hank and Dean and freaks out. They’re supposed to be dead. He knows because he killed them some time earlier. And again, it’s funny but it’s also not. The serial killer, the one who sees it as his brief to send souls off to the undiscoverd country, confronted with two of those souls returning? The Destroyer confronted with two souls undestroyed? It’s as serious and confounding idea as the scientist bringing the dead back to life.

And so there’s a showdown in the cloning lab, where Hank and Dean are confronted with their own confounding image, rows and rows of themselves (providing the show with its best line, “I think they’re in a ‘saw their own clones’ coma”). Ted and Sonny are ready to kill Hank and Dean, but we see that, as murderous as they are, they are, after all, mere amateurs. Brock is a highly trained, skilled professional, acting on behalf of a government (and the family he loves).

Dr. Venture comes in just in time to snap Hank and Dean out of their stupor, pulling, what else, a great, paternal lie out of his back pocket, a parental fib, prompting Hank and Dean to exclaim that Rusty is “the best dad ever!” bringing the episode full circle. The ultimate bad father has, magically, become the ultimate good father, at least in the eyes of his cruelly manipulated children, and that’s a lesson that needs to be learned, especially with an election five weeks away.

UPDATE: ![]() mcbrennan, typically, has spurred a few more thoughts, mainly about Dr. Venture and his back-up plan to, essentially, send his own children off to die as brainless zombies in an unnamed war. I was reminded of two Leonard Cohen songs. He was writing, of course, about Vietnam, but they will serve here:

mcbrennan, typically, has spurred a few more thoughts, mainly about Dr. Venture and his back-up plan to, essentially, send his own children off to die as brainless zombies in an unnamed war. I was reminded of two Leonard Cohen songs. He was writing, of course, about Vietnam, but they will serve here:

“Story of Isaac” contains this verse:

You who build these altars now

to sacrifice these children,

you must not do it anymore.

A scheme is not a vision

and you never have been tempted

by a demon or a god.

And “The Butcher” begins:

I came upon a butcher,

he was slaughtering a lamb,

I accused him there

with his tortured lamb.

He said, “Listen to me, child,

I am what I am and you, you are my only son.”

“She Loves You:” a closer look

Above: the young McCartney, pale and drawn, haunted by his recent encounter, and the ensuing recording. Is the awkward pose a kind of code? And why are the other Beatles obviously distancing themselves from McCartney? Are they worried about possible sniper fire?

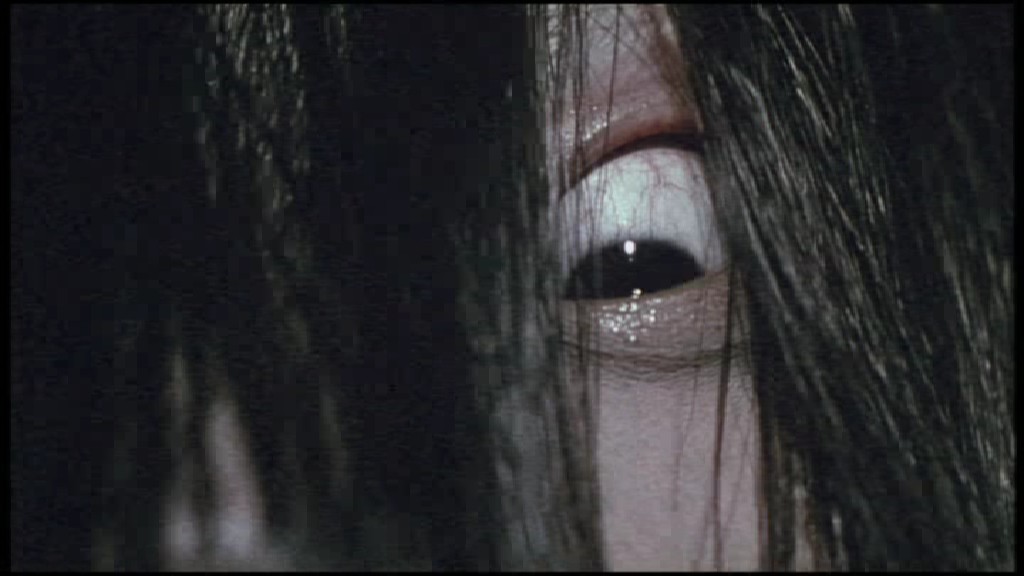

Below: the young woman in question.

______________________________________________________________

Your ex-girlfriend has a message for you. The message is, “She loves you.”

And you know that can’t be bad.

Can’t it?

Let us consider.

It is 1963. You are, presumably, a teenage boy, although the song does not specify age or sex. The point is, you have an ex-girlfriend and she says she loves you.

The question becomes: Who is your ex-girlfriend?

Your ex-girlfriend is, apparently, a person of considerable power and influence. How do we know this? We know this because Paul McCartney is her messenger boy.

McCartney, one of the most celebrated young men in the United Kingdom at this point, has recently been in contact with your ex-girlfriend and she has impressed upon him the overwhelming, urgent nature of her message, which is that she loves you. Not only is McCartney impressed, but he is sufficiently terrified of the repercussions of his failure to deliver this message that he has enlisted the aid of his band The Beatles, overwhelmingly the most popular and influential musical act in the UK, to assist him with this message delivery. McCartney, you see, apparently does not know you personally, nor does he know where to find you. All he knows is that your ex-girlfriend has a message for you and it is his urgent need to deliver this message.

And so McCartney has used every ounce of his compositional talent to craft a bombastic, hysterical football-chant of a song, immediate in its impact and devastating in its catchiness, and has enlisted The Beatles to play it, and on top of that has enlisted the aid of Parlophone records to distribute the recording to every record store in the nation, and Swan records in the United States (and, when their distribution capabilities prove inadequate, Capitol). Every radio station in the English-speaking world will be pressed into service to play it, and The Beatles will even sing a version in German on the off-chance that the message might reach you in Deutschland as well. On top of that, The Beatles, leaving no stone unturned, will eventually visit every civilized nation in the world (and Indonesia), playing this song in concerts before millions of listeners, and will continue to do so for three years, in a marathon attempt to deliver this message to you.

That’s some ex-girlfriend.

Who is she? How did she come to wield such power and influence? Why didn’t McCartney simply say to her “I’m sorry luv, I’m a rather busy pop star and this, frankly, seems to be a private matter?” What methods did she use to impress upon him the overwhelming importance of her love, so that he would spend the next three years of his life delivering the message, through recordings and live performance, to every possible recipient in the hope of reaching you? Your ex-girlfriend, it seems, has an iron grip on the attention of Mr. McCartney.

I think we have to allow the possibility that your ex-girlfriend is unstable and possibly dangerous.

What suggests this? Let’s examine the primary evidence, the message itself.

“You think you’ve lost your love, well I saw her yesterday, it’s you she’s thinking of, and she told me what to say.”

Seems simple enough. Let’s move on.

“She says you hurt her so, she almost lost her mind.”

Okay, let’s stop right there.

Your ex-girlfriend has instructed Mr. McCartney to write in his message to you that she has “almost lost her mind.” What kind of declaration of love is that? “Please come back to me, I’M NOT CRAZY.” This passage speaks volumes.

Now let’s go back to that first line. “You think you’ve lost your love.” Why were you trying to lose your love? What makes you think you’ve succeeded in losing your love? How intense were your efforts, and how diligent has she been in following you? And consider the subtext of McCartney’s desperation: “You think you’ve lost your love, well I saw her yesterday.” What he’s telling you is “You think you’ve lost your love, well, she she was able to get to me, Paul McCartney, the biggest celebrity in the UK, a man of considerable power and influence. What chance do you think you stand of avoiding her? Give it up, for the love of God, talk to her, PLEASE, TALK TO HER.”

And “I saw her yesterday.” Apparently she can get to him any time she wants. Note how in every performance of this song, and McCartney must’ve racked up thousands by now, he still sings “Well I saw her yesterday.” She is, for years, in near constant contact with one of the most heavily guarded personalities of his time. This ex-girlfriend, obviously, has her ways of getting to people, and does not give up easily.

(“Yesterday.” There’s that word, a word that would haunt McCartney for the rest of his life. He saw your ex-girlfriend yesterday; is it only coincidence that yesterday is the same day that so shattered him, that saw him reduced to “not half the man [he] used to be?” There’s “a shadow hanging over me” — a troubling image we will examine the implications of later.)

“But now she says she knows your not the hurting kind.” This line could be read a number of ways. Either your ex-girlfriend is confident in her abilities to overpower you physically (Why not? She’s got Paul McCartney wrapped around her little finger) or else she’s whistling in the dark. You have disappeared, fled this dangerous, unstable young woman, in fear for your life, and in her desperation she has crafted a fiction about the nature of your personality. “Come back, I know you didn’t mean to hurt me, I understand completely and I love you, and I won’t let Paul McCartney out of my clutches until you respond in kind, in order to prove my point.” What could this possibly be except the actions of a crazy person?

(In German! They recorded a version in German! Why? Has your ex-girlfriend expressed a concern that you perhaps have amnesia, and are living in Germany? Does she think, perhaps, that some German-speaking friends or relatives might relay the message to you? What evidence does she have of this? Does she think that, in your desperate avoidance, you have fled the country, changed your name and taken up speaking a foreign language? What the hell did this young woman do to you?)

“Although it’s up to you, I think it’s only fair.” Yes, that’s right, it’s totally up to you. Please don’t let me, Paul McCartney, biggest pop star in the UK, influence your decision in any way, it’s absolutely your decision to make. HOWEVER: “Pride can hurt you too.” Ah, there’s the rub. It’s utterly your decision to make, but YOU WILL FEEL THE PAIN OF THAT DECISION.”

“Apologize to her.” Oh, now wait, what the hell? I thought the message is that she loves you, now she’s demanding an apology? Not herself, of course, no, that’s not her style. No, it’s McCartney, McCartney is pleading with you, please, for the love of God, apologize to her, or you will find yourself in a world of pain. This is no tender declaration of love, this is a plain-spoken threat.

“And with a love like that, you know you should be glad.” Yes, you should be. But McCartney, at this point, is fooling no one. Look at the way certain phrases are repeated, chantlike, over and over — “She loves you, yeah yeah yeah,” “and you know that can’t be bad,” “and you know you should be glad.” This is what Shakespeare referred to as “protesting too much.”

An image forms in my mind. The Beatles return from a world tour, exhausted and terrified from their international mission of message delivery. A pale, drawn, shaken McCartney returns home to London, thinking he’s fulfilled his duty, but is greeted at his door by your ex-girlfriend.

The rain pours down, wetting the young composer’s hair as he stands, crestfallen at the sight of the trembling, enraged young woman. “Did you deliver the message?” She asks. “What was the reply?”

McCartney has no answer. Distractedly, he fumbles with a cigarette. He can’t get a match to strike, not in this sodden English weather. “I didn’t hear back,” he stammers, “I did my best. Please, you have to understand –“

“You didn’t even locate the recipient, did you?” she cuts him off. McCartney goes pale. The cigarette, soaked and lifeless, trembles in his lips. He knows that he will have to go back to the other Beatles and insist that they tour the world once again, enduring constant threat to their lives, in the service of this young woman. It’s going to be another long year.

(Did McCartney, perhaps, actually die in 1966, as was widely rumored? Was it at the hands of your ex-girlfriend?)

More important, perhaps: who are you? What did you do to this young woman, who must be a middle-aged woman by now, if she’s still alive? Are you still alive, or did you pay for your relationship with this young woman with your life? When will it be safe for you to come out of hiding? Are you waiting for another message from McCartney, a song whose chorus goes “It’s all right, she’s dead, you’re in the clear?” What will it take to heal this wound? Can your ex-girlfriend ever be satisfied?

Let’s face it, in the end there is only one possibility: your ex-girlfriend is a supernatural being of terrible power. Your ex-girlfriend may be, in fact, not your ex-girlfriend at all. The song does not, after all, identify her as an ex-girlfriend, merely that she is female, that you “hurt her so,” and that she loves you. She could be your daughter, your sister or even your mother. You may not even be aware of her existence, but she loves you and her love is powerful, constant and unstoppable. She could, in fact, be a ghost and, like Sadako in Hideo Nakata’s Ringu films, she will never rest until her message has been disseminated to every living person on the planet. Which begs the question: what did you do to her? You “hurt her so.” As per Sadako, did you push her down a well because of her awesome powers of destruction?

Whoever she is and whatever her powers, her mark on McCartney was permanent and irreversible. In three short years, she turned him and the other Beatles from cheeky, entertaining moptops to sallow bickering, paranoid drug addicts. What else explains the Beatles’ withdrawl from public life, their investigations into psychedelia and escape into hallucinations, John Lennon’s relationship with the Sadako-like Yoko Ono, George Harrison’s obsession with spiritual life?

What will free the world from the curse of her “love?”

8 1/2 off!

As part of my “movies about crazy directors making movies” research, I just watched Fellini’s landmark classic 8 1/2. I have nothing pertinent to add to the avalanche of praise that this dense, multi-layered, hallucinatory, infinitely graceful masterpiece has garnered, except to note that it seems to have inspired a number of imitators over the years.

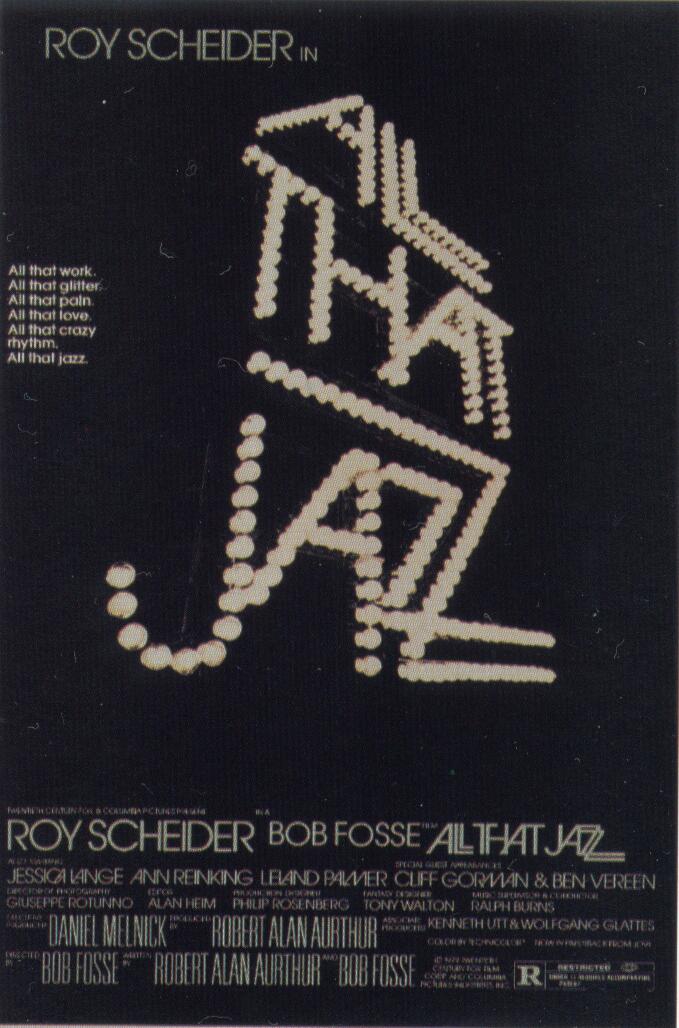

Because I was born into a provincial, parochial Chicago suburb with limited access to classics of European cinema of the 1960s, I probably saw both All That Jazz and Stardust Memories a dozen times each before I ever saw 8 1/2 but both of them strike me as not just “inspired by” the original, but practically direct remakes, at least as much as A Fistful of Dollars is a remake of Yojimbo and A Bug’s Life is a remake of Seven Samurai. (And The Lion King is a remake of Kimba. Or Hamlet, I forget which.)

Both Fosse and Allen lift Fellini’s structure, have their protagonists drift back and forth in time and from fantasy to reality, from the art their working on to the mental processes that create that art. Allen also lifts the black-and-white photography, the “extras as gargoyles” tone, and quotes pretty directly from the dream sequences as well. Fosse does all those things too, but filters it more through his own sensibility.

It’s a tribute to the quality of Fellini’s work that both of his imitators were inspired enough to turn in movies that are, let’s face it, both pretty freakin’ amazing in their own rights.

Who else is there? Are there other movies drifting around out there that we could say are remakes of 8 1/2? Tom DiCillo’s Living in Oblivion comes close, similarly weaving fantasy and reality, dreams and reality, “filmed reality” and reality (it also has more of a nuts-and-bolts attitude to production life — more problems with shooting, less conceptual agony). It has a much more programmatic structure and is more anecdotal in its approach, but serves as a kind of pocket-sized 8 1/2 — call it 4 1/4.

UPDATE: And now that I think of it, Adaptation, in its own way, is a valid entry in the 8 1/2 genre.

Sven Nykvist update

The New York Times reported the other day that Sven Nykvist’s “last film” was the thudding, club-footed rom-com Curtain Call, causing me no end of distress.

I am pleased to report that, while technically true, Curtain Call was not the last feature Mr. Nykvist shot. That honor belongs to Woody Allen’s thorny, scabrous, underrated, impeccably staged, luminously shot Celebrity. Celebrity was shot, cut and released into theaters while Curtain Call was still failing to find a distributor.

I can’t tell you how much better this makes me feel.

Munich

Narratively speaking, Munich is, literally, the oldest story in the book. A handsome young man is called upon to protect his homeland from a monster. He ventures out into the world to slay the monster, thus saving his homeland, but once he returns home he find that the experience he’s gathered in the world leaves him incapable of remaining there.

Thematically, complex questions of nationalism, tribalism, religion and ideology ping-pong and ricochet all over the place. But they all keep circling back to the prime Spielbergian themes of “Family” and “Home.”

And then there’s the question of “Home.” The Jews want a home, but so do the Palestinians. The espionage family has a wonderful, warm home in the French countryside. Everywhere Eric turns, people are falling in love, having children, setting up housekeeping, making plans. The terrorists targeted for assassination are shown bickering with their wives and doting on their children, going on dates and having parties. There isn’t an inhuman one in the bunch and they all seem to have nice homes and good families.

In terms of genre, something of a head-scratcher. It’s structured like an espionage thriller, like Three Days of the Condor, and certainly is as suspensful and gripping as that movie, but tonally it feels closer a historical drama like Schindler’s List.

Spielberg works very hard to keep things real and cliche-free and mostly succeeds (some cliches do slip through, such as the cold-blooded assassin cooly walking up a darkened staircase while slipping on his black leather gloves, or the espionage guys talking about assassinations and terror plots while slicing vegetables or tinkering with toys). The assassination sequences don’t look or feel like anything ever shown before. The assassins are human and prone to mistakes and improvisation. Nothing feels planned or flawless (unlikethe assassinations in Three Days of the Condor). For every cute Spielbergism that slips through, there are a dozen scenes of stunning originality, like the assassination of the woman in Holland. Not a pleasant film by any means, I had to take a break in the middle of watching it — not because of its unpleasantness, but to catch my breath, which I had been holding rather too much without realizing it.

Venture Bros: I Know Why the Caged Bird Kills

In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Shakespeare wrote “the course of true love never did run smooth,” and while this episode of The Venture Bros shares much with that play, including star-crossed lovers and magical spirits, I doubt Shakespeare could have ever come up with a path to true love involving Catherine the Great, Henry Kissinger, a haunted car and a refugee from American Gladiators.

As with any love story, “I Know Why the Caged Bird Kills” has two protagonists, The Monarch and Dr. Venture. Both protagonists have love problems (to say the least), but for the moment, neither protagonist can pay attention to them. (Typically for this show, the Monarch’s plot is active, with him trying to solve his administrative problems, while Dr. Venture’s plot is passive, with him merely trying to get rid of his immediate problem so that he can go back to his life of steadily increasing failure.)

The Monarch’s attention is taken up by an immediate problem, that his plans to attack Dr. Venture are failing. His henchmen (at least 21 and 24) believe that the problem is one of armament (which is absurd, as the attack shown at the top of the episode is the most well-armed and effective in The Monarch’s history). Meanwhile, Dr. Venture is being harrassed by a vengeful Oni.

Meanwhile, The Monarch is visited by a mysterious stranger, Dr. Henry Killinger and his magic murder bag. The Monarch, impressed with Killinger’s organizational skills, allows him free access to his staff and secrets. In no time at all, Killinger has an elite staff of Blackguards in cool suits and has completely re-organized the Monarchs’ operation (Literally, in no time at all. Killinger does all this in the time it takes for Drs. Venture and Orpheus to walk from the library to the parking lot).

Henchman 24, suspicious of Killinger’s intentions, refers to him as a “sheep in wolf’s clothing,” and while that sounds like a mere malapropism, it’s actually a key line in the episode. Because we see that, in each plot here, love comes disguised as hate, tenderness disguised as threat. Myra shows her love for Hank and Dean by kidnapping them, 21 shows his love for the Monarch by bringing in Dr. Girlfriend to infiltrate and assault the cocoon (and ends up falling in love with her, but that’s another story). I will also argue that the Monarch’s obsession with and attempts to destroy Dr. Venture also constitute a kind of love, one paralleled by Myra’s obsession with and attempts to destroy Dr. Venture’s family. (It also occurs to me that Henry Kissinger was the inspiration for Dr., ahem, Strangelove.)

And then of course there is Dr. Killinger, who turns out to be not a malevolent figure of doom but a magical spirit of love and reconciliation (would that his real-life counterpart turn out similarly), and the Oni turns out to be working for him. Killinger is shown to be a fat, male version of Mary Poppins, which, again, seems completely lunatic on the face of it, but underneath has a deep thematic resonance with the rest of the show.

The protagonist of Mary Poppins, lest we forget, is not Mary Poppins but rather the father. What does the father in Mary Poppins want? The same thing as Dr. Venture — to have someone, anyone besides himself take responsibility for raising his children. A key difference between Dr. Venture and Dr. Benton Quest is that Race Bannon is assigned to be a bodyguard for Dr. Quest’s son Jonny, Dr. Venture has hired Brock to be a bodyguard for himself; the boys’ safety is never anywhere on Dr. Venture’s list of priorities. Brock, the much better parent of the two, seems to take on the boys’ safety himself, but only to the extent that it’s usually too much trouble to clone them again. If the boys die, well, there’s always more where that came from. The father of Mary Poppins at least hires a nanny; Dr. Venture is content to leave that job to an inadequate robot and the “lie machines” that talk to them in their sleep. The father in Mary Poppins, of course, learns his lesson and re-centers his life around his children; Dr. Venture, I fear, will never learn that lesson.

The theme of this episode is the course of true love, but there is a sub-theme of misguided rescue. Hank and Dean, out practicing their driving skills, happen upon a stricken woman, who turns out to be a deranged ex-girlfriend of Dr. Venture. They set about rescuing her, but end up being taken captive by her. Later we will find that she feels that she is “rescuing” them from Dr. Venture. The henchmen misguidedly try to rescue the Monarch, and even take turns rescuing each other at different points of the episode.

Of the episode’s short-circuited love affairs, the most elliptical is the one between Drs. Venture and Orpheus, which seemingly ends with Dr. Venture hysterically accusing Dr. Orpheus of coming on to him, then mysteriously seems to begin again when he, minutes later, casually suggests that they watch pornography together. This rocky, contentious relationship is presented as a contrast to the other “true loves” of the episode.

In an episode rife with parallel scenes, Brock and Helper are given a nice pair where, in one scene, Brock attempts to educate Helper on the subject of Led Zeppelin, and in the next, Helper is educating Brock on the poetry of Maya Angelou.

The advice Dr. Orpheus gets from Catherine the Great’s horse is never revealed — but given the circumstances, that might be for the best.

(Strangely enough, although Myra’s story is explained away by Brock, her own version of events makes more sense. In her version, she rescues Dr. Venture’s life during the unveiling of the new Venture Industries car, and later the two of them have sex in that same car, and it is that car that the Oni chooses to haunt in order to bring Dr. Venture to Myra. So perhaps Brock’s story is the inaccurate one after all.)

Contempt

If Harold Pinter wrote a version of The Big Knife, it might come out something like this.

I’d be kidding you if I said that the movie struck me immediately as a masterpiece. Because it’s Godard and for me, Godard always comes off as willfully opaque and even boring on first viewing. It takes some time, in this case 18 hours and a good night’s sleep, for his narrative strategies to reveal themselves.

A french writer (A novelist? A playwright? We’re not sure; he describes himself as a playwright but his wife says he’s a “crime novelist”) living in Rome is hired by a boorish (that is, American) producer to “fix” a new film by director Fritz Lang (played by, well, director Fritz Lang). The film in question is an adaptation of “The Odyssey.” The director wants to put myth on screen, gods and goddesses and mermaids, heroism and simplicity. The producer wants to make Ulysses a “modern man,” ie neurotic and perverse, so that the audience will have a way into the story. The writer is caught between these two impulses.

None of this is immediately apparent.

The writer is married to Birgitte Bardot, the ne plus ultra of “desirable women” in 1963. He has, in other words, everything a man could want. He is offered the job by the producer and goes to the studio to watch what there is of the movie the director has made.

(The film, as shown, appears to be even more opaque and than the one we’re watching. Only a few of the shots are of actors doing things, the rest are shots of Greek statues posed in fields. When actors appear, they have no dialogue, only a few poses and motions. If the director was trying to resurrect the gods, he’s crashed on the shores of film’s limitations — a static shot of a painted statue does not evokes godhood, it evokes tackiness and pretension.)

After the screening, the writer, completely baffled, is invited by the producer to come back to his villa to talk. The producer offers the writer’s wife a ride in his Alfa Romeo and the writer encourages her to go. This action, for reasons that remain mysterious to the end of the movie, ends his marriage, although it will take him the rest of the movie to figure that out.

The producer asks the writer and his wife to come to the set in Capris that weekend and they part. The writer and his wife go home to their flat somewhere in Rome. We’re all set for an involving drama about the making of a motion picture, but Godard, as Godard will, dashes our expectations and instead gives us a half-hour scene in the couple’s apartment where the writer asks his wife, over and over, in a dozen different ways, if he should go ahead and take this job, and what happened that afternoon that has made her start acting so strange. Did the producer do something to her in the car? Did the writer say something to offend her? What the hell is going on? Birgitte Bardot is pissed, and one tends to want to know what Birgitte Bardot is pissed about. The couple putter around the flat, take baths and set the table, start twenty different halting, incomplete conversations, take off and put on clothes, hats and wigs, fight and make up and fight again and make up again. This scene takes up the entire second act of the picture and, like many things in a Godard picture, the purpose of it remains hidden for a while.

The writer and his wife, in any case, go to Capris. The writer takes walks through the wilderness with the director where they discuss what writers and directors have always discussed: What does the protagonist want? That is, Why does Ulysses go off to the war to begin with, and why does it take him ten years to get home? The director believes that that’s just the story, it is what it is, but the writer believes (or is being paid to believe) that Ulysses went to the war to get away from his wife and is taking his sweet time getting home because he’s not sure if he ever wants to see her again.

Aha, so that’s what the 30-minute Pinteresque flat scene was about. The writer whines and grumbles about how he wants the job and worries about whether his wife still loves him, when secretly he wants to both reject the job and get rid of his wife altogether. The man who has everything is intent on throwing it all away.

And so in the end (spoiler alert) the protagonist of this movie gets exactly what he wants, although not in the way he expected. Instead, the gods that the director wanted to put in his movie enter, as gods often do, offscreen, in the form of , literally, a deus ex machina. When I was a youngster, a high-school comp teacher warned that the weakest ending imaginable is “And then they were all hit by a truck.” Godard, surely, must have had that rule in mind when he devised the ending for Contempt, a fitting end for a movie about modern perversity.

Renaissance

Go.

See it on the biggest screen you can.

You have never seen anything like it. This I promise.

Required viewing for anyone with an interest in the art of animation.

The story is a sci-fi noir not unlike Blade Runner or Minority Report (but without the Dickian moral complexities); the look recalls Sin City but more styized (ironically, it looks more like a Frank Miller graphic novel come to life than that movie did) and the visuals are absolutely mind-blowingly staggering. Without exaggeration, I would say that there are more fresh ideas and innovations in any given three minutes of this film than there are in most other entire animated features.

Made me believe that there is still something new to say in the art form of film, that we haven’t quite reached the boundaries of this medium.