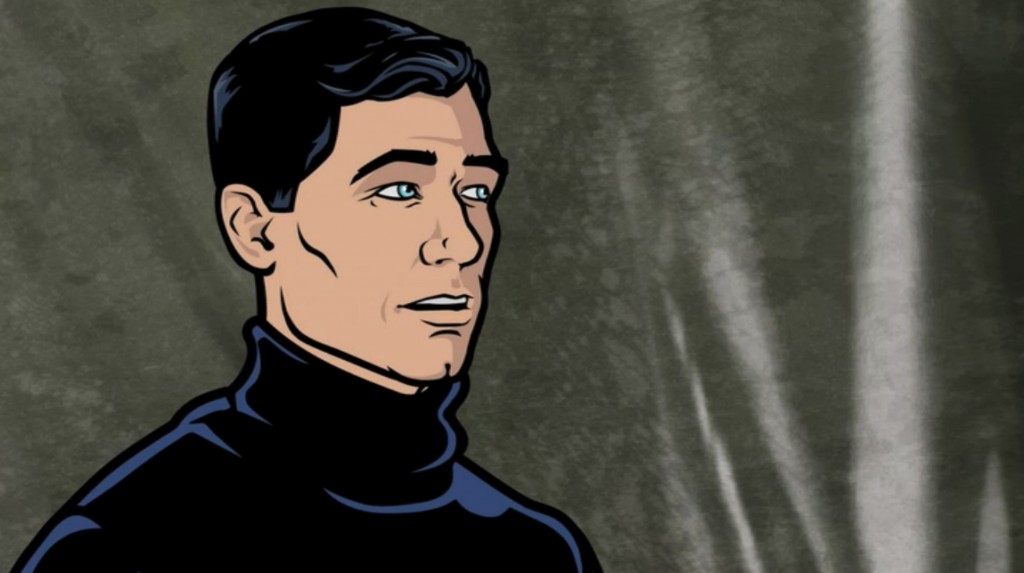

Archer: “Skytanic” part 4

Archer’s arc for “Skytanic” is:

(1) He has no interest in defending a rigid airship against a bomb threat, but goes on a mission to do so, in order to have sex with Lana.

(2) Once aboard the ship, he goes about his job of “finding the bomber” half-heartedly and incompetently, while still trying to have sex with Lana.

(3) His twin motives of “find the bomber” and “sex with Lana” conflict in the person of Singh, and force him to drive Lana into the arms of Cyril, his romantic rival.

(4) Finally, once it is revealed that there never was a real bomb threat, Archer discovers a very real bomb.

Archer: “Skytanic” part 3

Up in the sky aboard a rigid airship, Lana has reached a crisis point with her boyfriend Cyril. Dressed as a bellhop and bearing a basket of fruit, Cyril has stumbled upon Lana in her underwear with a naked Archer. Lana, fed up with Cyril’s mistrust, breaks up with him, and Cyril flees, sobbing. Archer, whose first priority is to have sex with Lana, tells her to “go after him.” Not to patch up their relationship, of course, but because “we’re almost out of fruit.”

Mind you, this is all in the service of foiling a bomb plot. That’s one of the key things to remember with farce — the higher the stakes are, the more serious the “mission,” the more base the cast’s motivations should be. In Fawlty Towers it’s “the hotel inspectors are coming,” in Arrested Development it’s “we’re going to trial,” in Curb Your Enthusiasm it’s “There’s an important party and you need to be on your best behavior.” With the Marx Bros it’s A Night at the Opera, with Bugs Bunny it’s “The Rabbit of Seville,” with the Three Stooges it’s the “important society gala,” with Caddyshack it’s the big golf tournament, with Animal House it’s the homecoming parade.

And one of the things that makes Archer that much more startling is that it’s, of all things, “a James Bond parody,” a genre unto itself, something that’s been done to death, in every possible medium, from Get Smart to Austin Powers, from radio to newspaper comics. How Archer manages to be not just fresh, but startlingly so, is a miracle unto itself, and a testament to the vision of the show’s creators, who have turned a liability into an asset — they use the “Bond parody” style as a familiar way into their extremely bent worldview.

Archer: “Skytanic” part 2

So, our team of self-involved, superficial super-spies are now on the Excelsior. But there is one key player we haven’t met yet — Cyril, Lana’s current boyfriend. Cyril, anxious and insecure on the best of days, can’t stand the idea that Lana is going to be spending the voyage in a cramped stateroom with his rival Archer, so he sneaks aboard the airship and disguises himself as a bellhop in order to spy on them. The perfect ingredient to raise the level of farce — a character with a secret, involved in a deception, and best of all in disguise. Add to that the enclosed space of the airship, the ballooning of free-floating sexual tension and the escalation of the bomb plot (which may or may not be real) and you have a farce narrative that would work under far less well-written circumstances. (It’s essentially the plot of The Hindenburg. “Skytanic” manages to cover the same ground with 100 minutes to spare and a lot more laughs.)

Archer: “Skytanic” part 1

We are living in a second golden age of television. Some of the best writing in any field is being done right now there, from the finely-calibrated social analysis of Mad Men to the demented dark fantasies of The Venture Bros. Somewhere in between those two shows lies Archer, perhaps the most consistently well-mounted farce ever presented. Comedy is hard, and farce is the hardest form of comedy, and the scripts for Archer manage to deliver quality, satisfying, twenty-minute farces on a weekly basis. Those twenty minutes fly by like a cool breeze but actually are hard won crystalline comedy. Today, let’s look at my favorite episode from Season 1, “Skytanic.”

Mindhunter vs One Neck

Watching the new Netflix show Mindhunter, I am reminded how the concept of “serial murder” was brand spanking new when I was a teenager, that killers like Ted Bundy, John Wayne Gacy, Jeffrey Dahmer and the rest were a terrifying new phenomenon to law-enforcement agencies, who had no vocabulary or protocol to deal with them. A novel like The Silence of the Lambs was capturing events that were still in the headlines, the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit being a weird experimental new idea in an FBI where Dillinger-hunter J. Edgar Hoover’s death was still a fresh memory. Suddenly the FBI went from gangbusting to psychology, which required men like the protagonists of Mindhunter to travel around interviewing serial killers, to try to understand how their crimes were possible.

When I sat down to write the play One Neck, I read a whole stack of books on serial murder, and none — not one — came close to a clear explanation for their subject matter. For a researcher, the quest to understand involves trying to get inside the mind of a sociopath, which puts one in a very strange, very dangerous mental place (which the show Mindhunter explores to an extent). I can still remember trying to capture the voice of “my” killer, Lucian, writing for months in my room in Brooklyn, and how, in order to achieve his voice, I had to abandon every scrap of what I knew about morality. I would spend nights writing, hunched over my Royal portable typewriter, and then venture out in the morning to go to work and the world would seem like a very strange place.

That was just from reading those books and struggling to write that character, I can’t imagine what it was like for the FBI agents and psychologists who were actually in the room with those murderers.

There has been exactly one good movie about serial murder, one that captures what it’s like to struggle with a mind like that, and that’s David Fincher’s Zodiac (Fincher is a producer on Mindhunter, and directed the first two episodes). There is one great play about it, and that’s Lee Blessing’s Down the Road, which is about a “true-crime” writing couple who decide to take on the job of interviewing a serial killer for a book and how those interviews destroy their marriage. When I saw a reading of Down the Road in the early 90s, I said “That’s it. That’s what it’s like.”

My play One Neck isn’t about about that obsession or the (thankfully temporary) damage it did to my psyche. Rather it’s about what happens when a piece of chaos crashes a dinner party in Long Island, a party starring the peak of western civilization: a scientist, a stock broker, a TV news producer, a painter and a lawyer. While it’s almost been a movie a number of times, the play is deliberately anti-dramatic. The first act is a comedy of manners, the second act is pure existential horror. (As I liked to say in rehearsals, the first act is The Man Who Came to Dinner, the second act is Endgame). The narrative invites the audience in the same way the killer does, by being funny, weird, honest and discomforting. Then, when it’s got your interest piqued, it goes in for the kill.

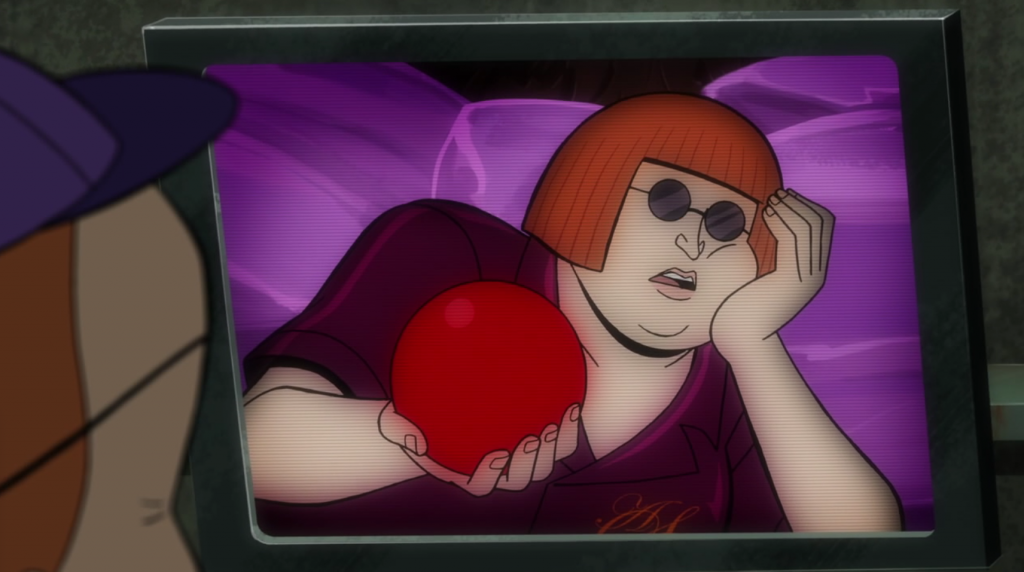

The Venture Bros “Maybe No Go” part 1

One of the most potent themes of The Venture Bros involves the question of the value of popular culture. Is it worthless garbage manufactured by corporations to distract people from the horrors those same corporations inflict daily upon the world, or is it a kind of magic, or both, or neither? The show might be a kind of a family saga, but it is also very much about the entertainment that reaches us when we are children. That entertainment, the shows and comics and commercials that hook us when we’re young, for better or worse, informs who we are as adults. It contains lessons about life, but also trains us to be consumers. I don’t think any episode of Venture Bros addresses that aspect of the theme better than “Maybe No Go.”

Out in the desert, the A-story of the episode begins with Billy Quizboy and Pete White experimenting with putting mouthwash in cookie dough (presumably for a cookie recipe). This experiment is taking place in their ancient trailer, under the broken neon sign advertising their company Conjectural Technologies. Obviously, business has been slow since the Ventures moved to New York, and no worthwhile inventions are coming down the pike.

Into this threadbare idyll comes a Truckasaurus operated by Augustus St. Cloud, the creepy collector of classic pop-culture memorabilia who has taken it upon himself to arch Billy Quizboy. “To the Quiz-Cave!” exclaims Billy, and we next see the opening titles to what I take to be an imaginary kids’ show starring Billy and Pete “The Pink Pilgrim,” done in the Hanna-Barbera style of the 1960s. The question is, if the show is imaginary, who is imagining it? My guess is Billy, who has lived too long in the shadow of Rusty Venture, who, even though he’s miserable because of it, once had his own TV show when he was a child. In taking on St. Cloud as an arch, Billy is, in his own way, getting out from under Rusty’s shadow and “getting his own show.” The entertainment of Billy’s childhood got into his system so completely, he’s willing to risk everything for a chance to join the party, as it were, and become his own super-science crime-fighter.

His fantasy is involved enough that, the next time we see him, he and Pete and their robot assistant are in the aforementioned Quiz-Cave, in their super-hero costumes, struggling to defeat the Truckasaurus attacking their trailer. The interesting thing about the scene, and the “Quiz-Cave,” is that, unlike, say, Batman and Robin going to the Batcave, where they analyze clues and hop in the Batmobile, the Quiz-Cave is entirely defensive in its effect. Even in his fantasies as an adventurer, Billy’s tendencies are inward.

The Truckasaurus, it turns out, is a mere distraction. Under this noisy cover, St. Cloud has stolen from Billy and Pete what appears to be a red rubber ball. Only a red rubber ball, but to Billy and Pete it’s “the holiest of holies” and “the source of all our powers.” The question of what exactly this ball is and what is its worth becomes the linchpin of the A-story.

The Venture Bros: “Hostile Makeover” part 2

Brock’s reappearance as the Ventures’ bodyguard very much indicates a fresh start for the series. And yet no fresh start in the Venture-verse is without casualties. In this case, Brock’s reinstatement means reassignment for Sgt. Hatred. A nobler character would take the change in stride, but Sgt. Hatred is not a nobler character, and the sight gag alone of the cut between Brock, above, and Hatred, below, is indicative enough of the two men’s characters: Brock is cocksure, respectful and upright, and Hatred is hunched, defeated and whining. He not only doesn’t take the setback easily, he refuses to take it at all, and stays on as the Venture’s unassigned stalker-bodyguard, sneaking around the Venture building and spying on the other security forces, looking for errors, echoing the more comic tension between HELPeR and the J-bots.

(On a more meta level, how cruel is this world, where Hunter S. Thompson is still alive in a cartoon, but David Bowie is not?)

The Venture Bros: “Hostile Makeover” part 1

It is a new season of The Venture Bros, and so it is time to once again ask “What does Rusty want?” “Hostile Makeover” answers the question before the titles even begin. Rusty wants his dead brother’s money, and receives it. Having outlived both his distant father and his parasitic twin, Rusty, who has lived in the past for so long, now has a new fortune to squander, and a new place to squander it in. Having been trapped since childhood in the dark, backward 1970s-Hanna-Barbera-netherworld of the Venture Compound, Rusty now has his own high-rise building smack on Columbus Circle in up-to-the-minute New York City. Now, perhaps, we can see him age in a 2010s-era Manhattan penthouse as his shiny new surroundings gradually get old and then burnish into nostalgia.

X-Men: First Class part 5

Erik, tracking the man he knows as Dr. Schmidt to Miami, surfaces, James-Bond-in-Goldfinger style, in the harbor near Schmidt’s yacht, the one with the boat’s name in Trajan. He climbs aboard the yacht and finds Schmidt (who of course is actually Sebastian Shaw), lounging with Emma Frost and Riptide. Erik has brought a knife, the Nazi dagger he got from the “pig farmer” in Argentina. He is, of course, thinking of the right tool for the job of killing Schmidt — a Nazi dagger reading “Blood and Honor” on the blade, he feels, should carry the right moral heft. He’s wrong in this, and it will take him until the end of the movie to figure out the right tool to use to kill Schmidt.

To Erik, it looks like Schmidt is a callow jet-setter with a bimbo and a manservant, or perhaps a bisexual playboy, but surprise! all three are mutants. Erik gets the full brunt of Emma’s powers — the mind-reading (“He’s here to kill you” she divines, using only her psychic powers, and maybe the fact that Erik has snuck aboard in a black wetsuit and is brandishing a dagger), the diamond-skin, a sonic blast that incapacitates him and, apparently, some telekinetic powers — rather a lot of abilities for one mutant — that blast him overboard. Shaw adds a moral wrinkle to the scene, chastises Emma: “We don’t harm our own kind,” he says, perhaps forgetting about that time he killed Erik’s mother.

Coincidentally, the Coast Guard shows up.

Movie Night with Urbaniak: She Wore a Yellow Ribbon

So urbaniak and I have been watching some of the classic John Ford-John Wayne movies. We started with The Searchers, because everyone does, and then moved to The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence, then Fort Apache. The result: Urbaniak feels that this Wayne guy could really be going places. "He’s my new favorite actor," quoth the thespian, who apparently had never really sat down and watched a John Wayne movie before. Not even True Grit.