Movie Night with Urbaniak: The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance

urbaniak and I are in the middle of a little John Ford – John Wayne retrospective. Last Thursday we watched The Searchers (because it’s out now on a spectacular blu-ray transfer) and tonight it was The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. (We’ve just finished a little "30s Gangster Movie" retrospective, having watched Scarface, The Roaring Twenties and Little Caesar all in a row, with The Public Enemy still waiting in its shrinkwrap.)

Can superheroes grow up?

voiceofisaac writes:

"So, if most superhero comic books are adolescent power fantasies, what about them would need to be changed in order to make them a more adult fantasy? Or are all power fantasies adolescent by definition?"

ted_slaughter ripostes:

"First, ‘adolescent’? Are you saying it’s adolescent to desire power, or that comics are inherently jejune? Because I beg to differ, on both counts.

Ted and Isaac cut to the core of the issue here. This is, in a way, the whole ball game.

First, let me make something clear: there is nothing wrong, shameful or second-rate about adolescent fantasies. Adolescent fantasies drive the entire movie business and have for more than a generation. "Grown-up" drama was once where all the money was spent in Hollywood, now it’s the opposite: all the money is spent on adolescent fantasies, while adult drama must squeeze itself in where it can. Adolescent fantasies thus call the shots in this world of professionals — movies based on superhero comics, fantasy novels, children’s books and pop-culture flotsam attract the biggest names, the highest salaries and our brightest talents. No offense to the wonderful movies nominated for Best Picture this year, but the three movies I went to see more than once in the theaters, Iron Man, Kung Fu Panda and The Dark Knight, are not on the list. The question here is not "are superhero movies any good?" but "can superhero movies ever be anything but adolescent fantasies?"

Spielberg: Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade part 1

WHAT DOES THE PROTAGONIST WANT? Indiana Jones, although still interested in historic artifacts, is here interested in a goal less tangible and harder to gain than a Peruvian idol or Sankara Stone — communication with his father.

The structure of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade is quite a bit more conventional than the structures of Raiders of the Lost Ark and Temple of Doom — those movies had four acts of roughly equal length, with three chapters in each act, for a total of twelve chapters. I find Last Crusade to be more conventionally structured, a straight-ahead three-act narrative with a prelude.

Coen Bros: The Hudsucker Proxy

THE LITTLE GUY: No Coen Bros movie illustrates their interest in social mobility more graphically than The Hudsucker Proxy. Norville Barnes is a hick from Muncie, Indiana who rises up, up, up in the sophisticated New York corporate world, then falls down, down, down and then, miraculously (the word is not too strong) rises back up to the top.

“Up” and “Down” are not mere words in The Hudsucker Proxy — they are story elements,almost characters. The action takes place in New York City, certainly the most vertical place in America, and largely within the Hudsucker headquarters, a 45-story skyscraper (44, not counting the mezzanine). Great emphasis is placed on the verticality of the building and what it means to its inhabitants. Norville begins his work at Hudsucker in the basement mailroom, a seething, windowless dungeon filled with oppressed humanity, and ends his work at the top, where the offices are huge, unpopulated rooms with vast floor space and high windows. Waring Hudsucker (the outgoing president) starts out at the top, both metaphorically and physically, but finds the top wanting, and so jumps out the 44th-floor window (45th, not counting the mezzanine) and plunges to his death. But we see by the end of the movie that Waring Hudsucker has risen again, this time into Heaven, before descending, yet again, to help Norville out of his problem.

So “up” is good and “down” is bad. Everyone wants to be “up,” no one wants to be “down.” Except for the beatniks, of course, who live “downtown” and whose oddball coffee bar is located in a basement. That’s just like those beatniks, turning the status quo on its head and drinking carrot juice on New Year’s Eve. Buzz the Elevator Gnat gets a great thrill from taking people up to the top or sending them down to the bottom. Norville Barnes must take a dozen different rides in that elevator in his journey from the bottom to the top to the bottom and back up to the top.

“Up and down,” it seems, in the world of The Hudsucker Proxy, are heavily loaded terms, full of danger and stress and sorrow. Fortunately, there is a solution: a thing that goes round and round, specifically the hula hoop, the blockbuster idea that Norville carries around in his head and The Hudsucker Proxy‘s narrative secret weapon. His blueprint for the hoop, a simple circle drawn on a piece of scrap paper, baffles and confounds all the Hudsucker employees who behold it. No wonder: they live in New York City (the most grid-like major city on Earth), and work in a building that’s all about rising up and falling down. There’s nothing “round and round” about their lives, and Norville seems either quite stupid or stunningly insane to them for thinking of a circle (the hoop prototype is even made crimson red, to better set it off from all the squares and rectangles in the board room).

The hula hoop, like the baby in Raising Arizona, is nothing less than a holy ideal, one the “squares” (another beatnik term!) in Hudsucker Industries aren’t quite ready for. In a world of up and down, Norville thinks in terms of round and round, and that makes him inscrutable, unpredictable and dangerous. And so much of the dialog around Hudsucker Industries concerns things going up and down and round and round. The business stock falls, then rises, then falls again, then rises again, four different characters are compelled to jump out the 44th floor (45th, not counting the mezzanine), while divine, ineffable notions are expressed in terms like “the great wheel of life” or “what goes around comes around” or “the music plays and the wheel turns.”

What besides divinity could explain the actions of the lone hula hoop, the one that escapes its death in the alley of the toy store to roll purposefully out into the street, through the grid of the small town streets, to circle a child and land at his feet (upon the firmly-stated grid of the sidewalk)?

(A scientist shows up in a newsreel to tell us that the hula hoop operates on “the same principles that keep the earth spinning around and around,” and keep you from flying off into space — an instance of science vainly trying to explain the divine, as though there were a quantifiable “reason” why the Earth spins.)

(We know that the hula hoop is a divinely inspired creation because Waring Hudsucker’s halo, at the end of the movie, is also a hula hoop. He even makes a comment about how halos on angels won’t last, are simply “a fad.”)

(The hula hoop is not the only “holy spinning thing” that shows up in Coen Bros movies. There is also the hubcap/lampshade/flying-saucer in The Man Who Knew Too Much and the bowling balls in The Big Lebowski.)

In between the square and the round, quite literally, is the big clock at the top of the Hudsucker building. The clock symbolizes Time, which, it has been noted, moves on (“Tempus Fugit” is the slogan of the newsreel shown halfway through, Tidbits of Time). Yes, time does move on, as we are reminded whenever we see the enormous clock hand sweep through the office of Sidney J. Mussberger. The narrator (another Coen mainstay), Mose the Clockkeeper, does not identify himself as God but that’s the role he plays in Hudsucker. Time is money, says Mose, and money is what makes the world go around, and that, I suppose, is why the round clock is fixed in its square hole on the side of the rectangular Hudsucker building. Because Time may be round, and so is the world (at least the globe in Mussberger’s office is) but Money is square in both shape and temperament, and I guess that means Mose’s job is to square the circle and keep everything in balance, which I suppose is why the clock in The Hudsucker Proxy is so influential. When the Hudsucker clock stops, everything stops (except the snow, oddly).

(That clock wasn’t chosen at random — it bears a startling resemblance to the clock in Metropolis — another movie where down is bad and crowded, up is good and roomy, and a clock rules the world.)

(Waring Hudsucker, when he appears as an angel at the end of the movie, sings “She’ll Be Comin’ ‘Round the Mountain” as he descends from the heavens — a small point perhaps, but he’s not singing about going up a mountain or coming down a mountain, which one would think would be the natural order of things in songs about mountains.)

(Mussberger, it should be said, has his own influence over time — he makes his clacking pendulum balls [five round objects in a rectangular framework] stop on command, something Mose also accomplishes when he stops the world in Act III.)

Mose explains in the opening narration that everyone on New Year’s Eve wants to be able to grab hold of a moment and keep it, but only Norville manages to actually do such a thing, because he is, alone among characters in Hudsucker, divinely inspired. (Well, except for Buzz, who turns out, incongruously, to have his own round idea.)

IS NORVILLE A MORON? This is the question that haunts The Hudsucker Proxy and which, I submit, accounts for its lack of popularity. For the plot of Hudsucker to have maximum impact, the audience must believe, as Mussberger and streetwise reporter Amy Archer do, that Norville is a blithering idiot. Then, when it turns out he is divinely inspired, we are to look at Norville in a new light. The trouble is, the Coens have cast Tim Robbins, an actor who oozes intelligence, to play Norville. To compensate for his innate intelligence, Robbins plays the part as though wearing a neon “DOOFUS” sign on his head. When I read the script, the story of Norville amazed me and made me weep. I could see what the Coens (and Sam Raimi) were after — a comedy along the lines of Mr. Deeds Goes To Town or It’s a Wonderful Life, with a helping of His Girl Friday thrown in for good measure. Trouble is, Gary Cooper and James Stewart and Cary Grant are all long dead, and Tim Robbins, although an excellent actor, is not a Gary Cooper or a James Stewart or a Cary Grant. When I read the script I imagined Tom Hanks in the part of Norville (Hanks would, of course, catch up with the Coens in The Ladykillers) — I’m convinced the star of Big would have knocked Norville out of the park. The result of Robbins’s casting is that Norville’s actions are all in big quotation marks — we don’t see a simple guy trying to front, we see an intelligent actor trying to convince us he’s a country-born rube. The actor holds the character at arm’s length, showing him to us, commenting on him, not quite able to inhabit him.

(I should note that Robbins’s performance is a symptom of a larger problem in The Hudsucker Proxy — the Coens have lured a huge raft of talented actors and instructed them to act in the style of 30s screwball comedies — a task they all pull off with great skill [I am particularly astonished of Jennifer Jason Leigh’s jaw-dropping rendition of Rosalind Russell]. The trouble is that that style of acting was a natural outgrowth of its time, not an homage to an earlier style of acting. Watch The Lady Eve [which Hudsucker explicitly quotes a couple of times] back to back with The Hudsucker Proxy and you’ll see exactly what I mean.)

(And while I’m here, I should note that the Coens, in their script for Hudsucker, have crafted an incredible simulation of a Preston Sturges 30s screwball comedy, but then, oddly, have set the story in a Billy Wilder sort of world of 1950s business comedies. That right there, I think, accounts for people not quite being able to get a handle on Hudsucker, despite its towering achievements. And I do mean towering — this movie, with one of the greatest scripts I’ve ever read, is a bursting cornucopia of invention, wit and bravura moviemaking.)

(And while I’m at it, I should not that I am not immune from this temptation. I once wrote a romantic comedy with roles for Cary Grant and Katherine Hepburn. Imagine my chagrin when I learned they were, in a big way, not available.)

A SECOND CHANCE: Norville fails, and falls, but rises again. Waring Hudsucker falls and rises, then descends and rises again. Waring Hudsucker could not give himself a second chance, but he posthumously grants one to Norville. It seems everything in The Hudsucker Proxy happens more than once — Norville comes into Mussberger’s office to show him his idea, only to get fired and collapse on the floor. Later, Buzz comes into Norville’s office to show him his idea, only to get fired and collapse on the floor. The music plays and the wheel goes round, humanity keeps repeating the same scenes over and over. And this might be coincidence, if not for Norville discussing reincarnation with Amy — in a way, Norville is both a reincarnation of Waring Hudsucker and his second chance. He arrives at the building the instant Waring hits the street in front of it, is instantly made president, and is ultimately granted all of Hudsucker’s stock — precisely so that he need not make the same mistakes that Hudsucker did. Norville believes in reincarnation and roundness, while Mussberger can only think of up and down, squares and “when you’re dead, you stay dead.”

Failure, Waring Hudsucker notes, whether in business or in love, looks only to the past, and the future, as it says on his big clock, is now. This is The Hudsucker Proxy‘s notion of Zen — there is no future, it insists, there is only the moment, grabbing it, holding it, and living in it. Ironically, it was the Coen’s first real commercial disaster, showing them how the real world reacts to the real Norvilles who come along with their divinely inspired inventions.

(Full disclosure: this writer has a tiny role in The Hudsucker Proxy — I would call it a one-line role, but since they messed with my voice, I’m not even sure if I have the one line any more. It was a lot of fun shooting it and maybe I’ll write a piece about that some day. But not today.)

Query

Let’s say I’m thinking of writing a western. In actual fact, I am thinking of writing a western, an idea I’ve had for a long time now, a western based on a classic work of literature. To say more would be to give it away.

If it is not too much trouble, I would greatly appreciate hearing your favorites, and why they are your favorites. Why do they work, why are they better than others, what do they all have in common (besides taking place in the Old West), where do they diverge, and why.

I thank you in advance for your cooperation.

The Gods Must Be Crazy

It is not the goal of this journal to heap scorn, so I will keep this brief.

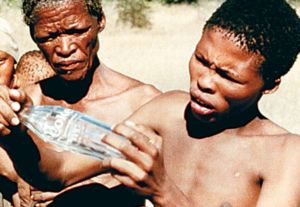

In the early 1980s, the movie The Gods Must Be Crazy was a surprise worldwide smash hit.

Why? Well, it has a delicious premise — a Coke bottle falls out of the sky (tossed from a passing airplane) and is found by a tribe of Bushmen in the Kalahari desert. The bottle, being unique and beautiful, leads to jealousy and conflicts in the tribe. So the leader of the tribe, Xi, decides to travel to “the end of the Earth” to return this gift to the Gods who, Xi believes, dropped it. As he travels to the end of the Earth, he encounters civilization, and civilization is shown to be ugly, cruel and insane compared to the simple, edenic life of Xi’s blessed, carefree people.

In addition to the premise, it showed, or claimed to show, the world something it had never seen or heard before — “real” Bushmen (that is, non-actors) and their click-consonant language.

People were amazed that, in the go-go 1980s, there were still “savages” living in total innocence, peaceful, child-like people whose world could be turned topsy-turvy by an object as innocuous as a Coke bottle. The movie’s fake National Geographic-documentary format helps reinforce this notion.

Wikipedia informs us:

“While a large Western white audience found the films funny, there was some considerable debate about its racial politics. The portrayal of Xi (particularly in the first film) as the naive innocent incapable of understanding the ways of the “gods” was viewed by some as patronising and insulting.”

Count me in!

Now, I’m a storyteller by trade, so I understand the comedic potential in viewing civilization through the eyes of a naif. It worked in Splash, it worked in Being There, it worked in Forrest Gump, it worked in Crocodile Dundee. But those movies weren’t pretending to show us “real” naifs; they employed professional actors to pretend to be innocent. The Gods Must Be Crazy got its international frisson by telling us that its protagonist was a real innocent, the comedic equivalent of a snuff film. “Watch as a genuine innocent gets humiliated and corrupted by the evil, evil West!”

What is “patronising and insulting” about the filmmaker’s treatment of the Bushmen in general and Xi in specific? The narrator tells us, many times, that conflict is unheard of in the Bushman world, that they don’t have words for “fight” or “punishment” or “war.” This may or may not be true; the writer (who is also the director, producer, cameraman and editor) presents it not for its factual basis but for its potential for comedic juxtaposition. The Bushmen were living in Eden and then this wicked, wicked Coke bottle fell out of the sky and brought conflict to them.

Now, I’m trying to think of something more insulting, more patronising one could say about a people than that they have no conflict, and no notion of conflict in their lives, and it’s not coming to me. To call such people “childlike” is an insult to children, whose lives positively boil over with conflict. To call such people more “natural” is an insult to Nature, which is defined as remorseless, brutal and ceaselessly ridden with conflict.

The DVD of this movie comes with a 2003 documentary, wherin a vidographer travels to Africa to find the tribe of N!xau (the actor, or non-actor, playing Xi) to find out for himself how much of The Gods Must Be Crazy‘s presentation of the Bushmen’s world is accurate. I could have saved him the time, because the falsehood of the movie’s premise is right there on the screen; the Bushmen of the movie are flabbergasted by the sight of a Coke bottle, but not of a film crew, recording their fictional actions. This is the height of insult in this loathsome movie — the filmmaker goes to the Kalahari, explains to the tribespeople who he is and what he’s trying to accomplish, puts the “genuine” tribespeople in costumes (or lack of them), constructs a fictional world they live in, asks them to perform comedic pantomimes illustrating a dramatic situation (“now, pretend you’ve never seen a Coke bottle before — it’ll be comedy gold!”), gets convincing, “authentic” performances from them, records it all on film, then assembles the finished movie to convince people that they are watching genuine innocents cavorting in an unspoiled Eden. And the white people of the Western world eat it up.

The insult to Xi and his people is compounded as Xi gains his education in civilization. He is put through hell in the form of the local justice system, with arrest, convicition and imprisonment for a crime he does not understand, and yet he remains, of course, thoroughly innocent, bewildered by what is happening to him. So apparently he is not only innocent, he is stupid and unconcerned for his own welfare. Not only that, he goes through his entire ordeal and apparently never sees another Coke bottle, or anything resembling such, never puts together that the magical, evil item that has beset his existence is, in fact, a common item of little consequence. That would make him a very stupid innocent indeed, but that is how the filmmaker presents him.

None of this would matter if the movie happened to also be a comedic gem, but it is not. It has a terrible script, wherin Xi’s quest to venture to the end of the earth is quickly shunted aside for unrelated storylines concerning a bumbling terrorist group and a bumbling researcher’s attempts to woo a pretty young schoolteacher. Sooner or later, all the storylines meet up, and wouldn’t you know it, Xi’s naivety and savage ways come in useful for the white people in the attainment their goals. In true western film tradition, and just so you know where the filmmaker’s heart truly lies, the white couple end up with most of the screen time and are given top billing.

The comedy is exceptionally broad and grating, and most of it operates at the level of an episode of Benny Hill, complete with copius undercranking and music-hall piano.

The technical aspects are abysmal; the image is washed-out, grainy and flat, and most of the sound seems to have been dubbed, badly, by amateurs.

Hulk

A number of extremely talented people worked to try to make this the best movie possible. It’s hugely ambitious and has a complex, elaborate editing scheme. I liked it a lot better than I did when I saw it in the theater.

I wish I had a better understanding of exactly what the hell is going on in it.

This paragraph from A.O. Scott’s review in the New York Times sums up my feelings regarding the plot:

“I’m far from an expert in such matters, but I would have thought that a combination of nanomeds and gamma radiation would be sufficient to make a nerdy researcher burst out of his clothes, turn green and start smashing things. I have now learned that this will occur only if there is a pre-existing genetic anomaly compounded by a history of parental abuse and repressed memories. This would be a fascinating paper in The New England Journal of Medicine, but it makes a supremely irritating — and borderline nonsensical — premise for a movie.”

And I also agree with this paragraph:

“All of this takes a very long time to explain, usually in choked-up, half-whispered dialogue or by means of flashbacks inside flashbacks. Themes and emotions that should stand out in relief are muddied and cancel one another out, so that no central crisis or relationship emerges.”

The tone sways wildly from ponderous to outrageously campy, sometimes in the same scene. At one moment a father and daughter discuss the unpredictability of the human heart, at the next moment the daughter is attacked by a giant mutated poodle. At one moment the Hulk is smashing tanks and swatting down helicopters, the next moment he’s lounging on a hillside contemplating lichens with a misty, faraway look in his eyes. At one moment a father and son have a colloquy on matters of identity and social order, the next moment Nick Nolte is gnawing on an electrical cable.

There are three bad guys, and none of their plots seem to make any sense. The biggest of them, which gets a very late start at an hour and eighteen minutes into the movie, involves Nick Nolte turning on some kind of machine and huffing on some sort of hose, then turning into some kind of super-being with some kind of super-powers which are visually impressive but which also seem tacked on, forced and incoherent.

There seems to be some kind of battle going on between the creative team and the genre they’re working in. They’ve chosen to make a movie about an enraged green smashing guy, but they also want the movie to be about “deep” themes and ideas. They’ve given their protagonist an inward journey (“Who am I?”) instead of an outward problem (“I’ve got to stop the bad guys”) and so the narrative seems choked, static and listless at just the points where it should be fleet, extravagant and larger-than-life.

Then there’s some problems with the plot. I’ve seen the movie twice now and there’s things I just don’t follow. I think I know why Hulk’s dad tries to kill him but I don’t know why he set off whatever green bomb thing he set off, or what the consequences of the blast were. I know in the comic book, it’s the “gamma blast” that created the Hulk, but here the script takes great pains to explain that the blast had nothing to do with it. Then why is it in the movie?

Then there’s the matter of the General’s daughter. This is a movie about, among other things, intergenerational conflicts, and so in addition to a scientist who has problems with his scientist father, there is a daughter who has problems with her general father. And the plot has to bend itself into a pretzel in order to keep those conflicts afloat, which is too bad because there isn’t much interesting going on in them.

But for the record, here goes: A Long Time Ago, there was this army base, see? And there was this general. And the general had a daughter. And the general was tussling with this scientist, who blew up the base with the Gamma bomb and then ran home to try to murder his son. And then many years later, the son grew up, forgot all about his murderous father, and then became a scientist, where he, by sheer coincidence, began studying in the exact same field as his murderous father, alongside the general’s now-grown-up daughter! This is a plot to make The Comedy of Errors seem like the acme of observational behavioralism.

Then there’s whatever Nick Nolte turns into. It’s pitched as the big battle that the narrative has been leading up to all this time, but it comes off as a late attempt to kick the movie into gear. Nick Nolte argues with his son, bites into an electrical cable, becomes a Big Weird Thing, then flies off, somehow, with The Hulk, to Some Place Far Away where the two of them fight as Nick turns into rocks and water and lightning and ice. Then a jet comes by and drops some kind of Large Bomb on them and somehow that takes care of Nick but also leaves Hulk alive. If anyone has any idea what any of that is supposed to mean, please let me know.

Then there are the special effects, which never quite take off. There are moments of great visual flair and compelling action, although the titular Hulk never really seems to be part of the scene he’s in. That’s okay, I don’t quite buy the special effects in the Spider-Man movies either. The difference, I think, is that the Spider-Man movies are pulp, understand they are pulp and function well as pulp, carrying their cliched truths lightly and with grace, while this movie slows down so often to think about “serious ideas” that it gives you too much time to realize how silly all of it is.