Batman: The Dark Knight Rises part 8

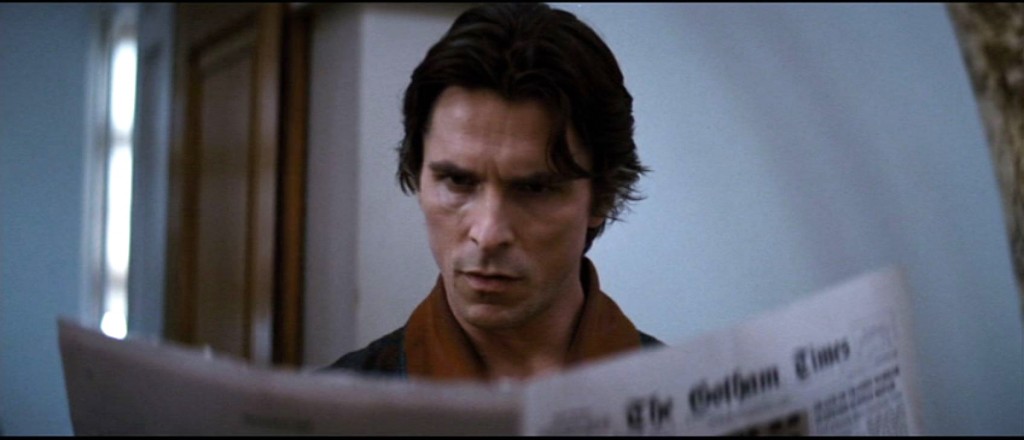

In Act I of The Dark Knight Rises, Bruce’s goal is “to hide.” In Act II it became “to emerge.” Act III his goal seems to be “to lose.” The act of emerging, even though that emergence was in defense of his beloved Gotham (he didn’t know Bane was robbing him personally at the stock exchange) has left him bereft. Alfred, his father-figure, is gone, and even the rain can’t keep from pouring down upon him as he pauses to take stock (sorry) of his losses. At this low point (not to be confused with the low point, which is still to come) here comes Miranda Tate, to whom Bruce has given Wayne Enterprises (“I’ll take care of your parents’ legacy,” mwah ha ha), to pull Bruce together.

Batman: The Dark Knight Rises part 7

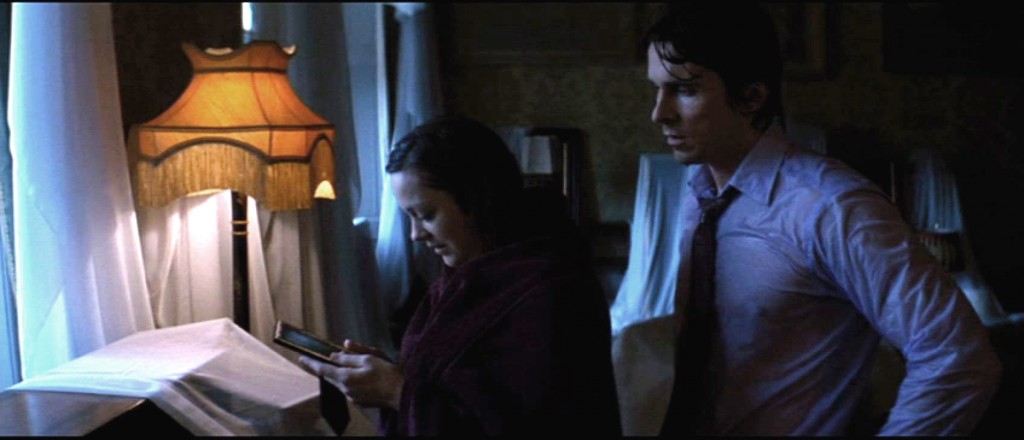

Lucius Fox comes to Bruce’s now-Alfredless house to deliver the bad news: Bane’s hit on the stock exchange, where he used Bruce’s Selina-stolen thumbprint to approve some very bad stock buys, has left Bruce broke. (Comics readers know that Bane, historically, “broke” Batman physically — his punishment for Bruce Wayne is more fitting. You break Batman physically, you break a billionaire financially.) (Note that “billionaire playboy” is no longer Bruce’s job description, but rather “billionaire recluse.”) Broke Bruce means that John Daggett can now take over Wayne Enterprises, which means that he has control over the “save the world” project, unless Bruce can put seeming good-guy Miranda Tate in charge of the company.

Batman: The Dark Knight Rises part 6

One bright day, Bane and his minions take over the Gotham City Stock Exchange. Let’s break this down.

Batman: The Dark Knight Rises part 5

The next step on Bruce Wayne’s road to recovery is stopping in to see Lucius Fox, the inventor to whom Bruce entrusted the running of his company back in Begins. Lucius finally brings Bruce’s monetary woes into focus — he spent his entire research-and-development budget on this mysterious “save-the-world” project, then cancelled it, leaving Wayne Enterprises ripe for takeover by industrial predator Daggett. (If Harvey Dent was Daytime Batman, John Daggett is Overground Bane, taking over Bruce’s legitimate business while Bane prepares to go after his darker identity.) Note that the screenplay still doesn’t tell us what the project is, exactly. Because what the project is is the maguffin of the piece, and if we know what it is too soon, it tips the narrative’s hand in undesired ways. Suffice to say that the comely Miranda Tate was instrumental in developing said project, and that Lucius strongly supports Bruce settling down with her. And, when Lucius is played by no less a personage than Morgan Freeman, the viewer takes it on faith that if Lucius wants you to settle down with a particular woman, you should probably do that.

Batman: The Dark Knight Rises part 4

With Jim Gordon hospitalized, John Blake emerges as a significant secondary protagonist in The Dark Knight Rises a kind of “young Gordon.” What does Blake want? Blake wants Bruce Wayne to stop sitting around feeling sorry for himself and become Batman again.

Now then. Some have expressed discomfort with the idea that John Blake, Rookie Cop, knows that Bruce Wayne is Batman while neither Jim Gordon nor any other citizen of Gotham City has apparently even given the matter a moment’s thought. This, for me, goes hand in hand with other narrative contrivances that occasionally poke through the cloth of Nolan’s Batman trilogy. The presentation and production design of these movies is so grounded, so realistic, it’s easy to forget Batman’s pulp roots, nay his operatic roots, and moments like “Blake knows Bruce Wayne is Batman,” in my experience, are endemic to the genre. I’ll say it again, the moment you decide to make a movie about a man who dresses up like a bat to fight crime, you enter the realm of the fantastic. The reader may remember my analysis of Batman and Robin, where I discovered that the psychedelic outrages of that screenplay all stem from the choice of making the flamboyantly fantastical character Mr. Freeze the chief antagonist of the piece — once that decision was made, everything else had to be made that much more crazy to fit that character. A similar thing happens here: as much as director Nolan wants to ground his Batman movies, the fact remains that they are about a man who dresses up as a bat to fight crime. Thousands of creative and narrative choices flow from that single plot point. Since that single plot point is flat-out absurd, it greatly affects everything that flows from it. In this case, wait, why hasn’t anyone, anywhere, even tried to figure out who Batman is? If a movie tried to address that question in any realistic way we’d be here all day, and the narrative would quickly spiral out of control as the thousands of questions raised by a man dressing up as a bat to fight crime would echo down and down and down until the very thing we get out of a Batman story — that is, the metaphor — would be lost. That’s why narratives like The Dark Knight Rises needs occasional contrivances like “Rookie Cop Figures Out Bruce Wayne is Batman” (or “SEC Approves Trades Made By Terrorists at Stock Exchange”). Anyone whose disbelief crashes down at this juncture would fall down dead if the same everyday logic was pressed onto any other aspect of the narrative.

Batman: The Dark Knight Rises part 3

The time has come to ask: What does Bruce Wayne want?

We’ve seen that he’s eradicated organized crime in Gotham City, so theoretically he’s overcome the sense of helplessness he felt about his parents’ deaths — there will be no more Joe Chills running around making orphans out of billionaires’ sons. Now, it would seem, he’s looking for a way out, a way to move on, to finally emerge from his cave, bury his parents and his girlfriend (and her boyfriend Harvey Dent) and become a fully-integrated man. The Dark Knight Rises is, at its heart, a dramatization of how a world-class control freak finds a way to let go.

But “to let go,” that’s not what he wants, that’s what he needs. What he wants is the opposite: to close the world off, to brood, to pout, essentially, to consider his losses and to hell with the world.

Batman: The Dark Knight Rises part 2

We’re still at the Dent-related function at Wayne Manor, and there are still characters scurrying around to meet. John Daggett is some level of businessman, disliked by Alfred and apparently by Miranda Tate as well, a dissolute lout who opines that Bruce Wayne pounced off with his investors’ money with his “save the world” project, and offers to get Miranda her money back in his own way. Miranda, it seems, shares Bruce’s ideals and snubs Daggett. In keeping with the theme of deception, Daggett thinks Bruce has deceived his investors and Miranda thinks Daggett is deceiving her. Later, we will find that Miranda was deceiving everybody.

Batman: The Dark Knight Rises part 1

The “titles” of Batman Begins showed the symbol of a bat formed in a swarm of bats, the titles of The Dark Knight showed it in fire, now The Dark Knight Rises shows it in ice. The bats in Begins were a symbol of fear, the titles a metaphor for an identity forming out of shadows. The fire of The Dark Knight was like a wall of fire for that bat, that symbol, pushing through the chaos inflicted by the Joker. Now, the bat is, literally, the cracks in the ice formed by the isolation of Gotham City at the hands of Bane. “I knew Harvey Dent,” Jim Gordon lies, as the title image gives way to a scene of Gordon addressing a memorial service for the late District Attorney, “I believed in Harvey Dent.” Gordon is not speaking of Dent at all but of Batman, the man who (the reader will recall) took responsibility for Dent’s bizarre chance-induced crimes, became Gotham’s Dark Knight so that Dent could remain its White Knight, its Daytime Batman as it were. Thus caught up, the viewer is plunged into a new story.

Spielberg: The Adventures of Tintin part 8

Tintin and Haddock are at an impasse. Tintin has lost the scrolls and his story, which means, to him, his identity — he is his story. Haddock has lost his ship — again — and thus his connection to his family. Tintin, despondent, is ready to give up, but Haddock bucks him up with what he intends to be a big inspirational speech on the nature of failure. Haddock succeeds, but not in the way he intended — instead, his truncated inspirational speech gives Tintin a practical idea, to track Sakharine by radio. Spielberg builds up a sentimental moment, then sweeps away the sentiment with a nuts-and-bolts answer — Tintin is not about introspection but action.

Spielberg: The Adventures of Tintin part 7

Tintin and Haddock journey by camel to Bagghar, getting there just ahead of Sakharine in the Karaboudjan. Where are we now, in the structure of The Adventures of Tintin? Good question. Timing-wise, the grand transition from Tintin and Haddock in the legionnaire’s camp to them arriving in Bagghar falls at 1:12:00, with 34 minutes left to go in the movie. Given an assumption of acts of equal length, that would make the move to Bagghar a natural move into Act III. But don’t forget, act breaks are not about location or transition, but about the journey of the protagonist. In Act I, Tintin became embroiled in a mystery that led him to be taken aboard the Karaboudjan, an irreversible direction, led to by a choice but not a choice in and of itself (although Tintin would have surely tried to sneak onto the Karaboudjan on his own, given the opportunity). Act II is then divided into three parts, typical of Spielberg: meeting Haddock, travelling with Haddock, and acting with Haddock. The entrance into Bagghar is only the beginning of that third chapter of Act II. And, as we’ll see, the traditional end-of-Act-II low point, where the protagonist has lost everything “but there was one thing he’d forgotten,” comes with a mere 14 minutes left in narrative. All of Tintin is brisk, but that’s super brisk for Spielberg. And yet, it’s not necessarily brisk for animation — many classics, for whatever reason, dating back to Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, follow what Jeffrey Katzenberg once explained to me as a “10-10-4” structure: 10 beats in Act I, 10 beats to Act II, 4 beats to Act III, Act III being, as Katzenberg described it, “a race to the finish line.”