Wonders never cease

Who doesn’t like chocolate? Not me! I love chocolate!

Who doesn’t like bacon? Nobody, that’s who! Everybody loves bacon! Pigs love bacon! If I was a pig I would regularly undergo belly surgery so that I could have an endless supply of bacon.

From the dawn of civilization, people have eaten chocolate, and also bacon. Why, oh why, has it taken from then ’til now to put the two together?

My wife brought home this curious artifact today, “Mo’s Bacon Bar,” described as containing “applewood smoked bacon, Alder wood smoked salt, and deep milk chocolate.” My son Sam (6), who sees absolutely no reason why bacon and chocolate should not commingle, dove right in and rushed to be the first to try this new confection. I followed suit, and Mom, more out of curiosity than craving, took a small piece.

It’s seems odd to say it, but it tastes exactly like bacon, and chocolate. As though you had, perhaps, a piece of bacon and then a little square of chocolate. Or perhaps a thin square of chocolate, then a thin slice of bacon, then another thin slice of chocolate on top, a little chocolate-and-bacon sandwich. Neither flavor overpowers the other — you don’t say “You can really taste the bacon!”, it’s actually rather subtle. And chocolatey, and bacony.

On the back of the package is an essay by the treat’s inventor, explaining herself. As well she should.*

For more information on chocolate and bacon, consult your local library. Or go here.

for pointing out that, although the name “Mo’s Bacon Bar” led me to believe the inventor was a man named Mo, the inventor of this confection is, in fact, a woman. Named Katrina. Go figure.

Story structure: it’s not just for movies anymore

It is 1995 and I have purchased my first PC.

A friend of mine tells me about this game Doom that is the wildest, scariest, freakiest, most addictive thing he has ever encountered. I happen across a free shareware version of the game at Staples and think “What the heck, I’ll try it.”

The next 24 hours or so are a blur. I’m aware afterward that my arms hurt from working the keys so frantically for such an extended period of time, but otherwise it’s just me and the game.

Shortly thereafter, the folks who made Doom also make Quake, a game where you play, um, some kind of soldier, again trapped in some kind of weird science-fiction world where hideous, stomach-turning monsters wait for you within ingeniously-designed castles and laboratories and whatnot. Quake is somewhat more imaginative than Doom, features monsters ranging from angry knights to exploding blobs of blue protoplasm, has weapons like a nailgun and some kind of lightning-shooting thing, and a dense, suffocating score by Trent Reznor. Again, you’re given no explanation as to who you are or why any of this is happening. Again, you’re on your own, abandoned, left to figure things out for yourself. Instead of getting to a room with a button, you move from “slipgate” to “slipgate,” a kind of teleportation pad that takes you to the next level. Somewhere in there it’s mentioned that this “slipgate” technology is the key to the whole situation: some military scientists (I think) have developed this teleportation device to transport equipment from place to place and in the process have accidentally opened a portal to another dimension.

And time goes on, and Doom and Quake have many, many sequels and spinoffs and ripoffs and imitations and I enjoy playing a lot of them.

Then along comes Half-Life. It’s only a few years later (1998) but it feels like a hugestep forward in gaming. After five minutes of Half-Life, Doom and Quake and their progeny feel crude, silly and pointless. In Half-Life, you fight your way through recognizable spaces with specific purposes, offices and hallways and research labs. The creatures you’re fighting are just as horrifying as those in Doom or Quake, but there is an unnerving psychology to them — they don’t merely attack, they think and scheme, lay traps and panic. You have friends and allies, clear goals and specific, logical destinations and a complex motivation.

Half-Life is hugely involving, much more so than the earlier games, a whole world to get lost in, and I am playing it for two weeks before I realize that it has, essentially, the exact same plot as Doom. You’re on Earth, sure, and you’re a scientist instead of a soldier, but otherwise the games are the same — hideous monsters appear out of nowhere because, yes, scientists have developed a teleporter that has accidentally created a portal into another dimension.

I am dumbfounded — the two games are conceptually the same to the point of copyright infringement, but feel completely different. How has Half-Life managed to do this?

The difference, it will not surprise readers of this journal, is story structure. In Half-Life, you’re not an anonymous grunt, you’re a specific person with a specific purpose. You’re not in some formless, pointless structure, you’re in a detailed, recognizable space, one you can relate to, a place with filing cabinets and worn linoleum tiles and a dropped ceiling and soda machines and telephones. This makes the monsters more disorienting and terrifying — they seem to be as frightened of you as you are of them, the difference being that they shoot lightning out of their hands to defend themselves.

You work your way through the thrilling, terrifying, underground, Area-51-type research lab known as Black Mesa with only one goal in mind — get upstairs. You are repeatedly told that your only hope for survival is to get to the surface. The drive to move ever upward becomes paramount, and the suffocating sense of being trapped in an underground complex with these horrible creatures becomes unbearable.

Finally you reach a freight elevator that will take you to the surface. Marines are there to rescue you — hooray! You made it! The game is over!

Except it’s not. No, it turns out that the marines aren’t there to rescue you, they’re there to kill you — they’re there to kill everything in Black Mesa. And they may not look as scary as the monsters from the other dimension, but they’re twice as smart and they don’t get confused.

And you realize — the difference between Doom and Half-Life is that Half-Life has a genuine plot, an ever-unfolding mystery that gets weirder and more frightening as the game goes on. Doom is a great game, but Half-Life is a great narrative. It’s like a movie and you’re in it, influencing the plot and at the center of the action. There’s a sense of unspooling narrative that simply isn’t present in Doom, and every time it seems like the drama cannot escalate any further, it does, in frightening and unexpected ways. The other characters have differing personalities, the fights have different structures and brilliant choreography.

You fight marines and monsters on the surface and through the labyrinthine passageways of Black Mesa, and finally you come to the secret of the catastrophe, the teleporter complex that started it all. For the second time, just when you think the game is ending, it takes another unthinkable twist — you must now go through the teleporter, alone and unarmed, to the alternate dimension to destroy whatever intelligence is sending the monsters through. Youthink this might be a single “boss” level, but no, it turns out it’s a whole new world that goes on for another whole third of the game. And you realize that Half-Life has, in fact, a classic three-act structure. Act I is “get to the surface, help is on the way” Act II is “help is your enemy, you’re on your own,” Act III is “stop running and face the evil.” The “twists” are a-line action-movie caliber, and there’s even an end-of-Act-II “low point” where you realize you have to leave your dangerous-but-recognizable world to fight monsters in an alien landscape with its own rules and physics.

I walk around in a daze after playing Half-Life and I realize I’m living through the birth of a new medium. Just as movies began as novelties shown before “real” entertainment, or as nickel entertainments in amusement arcades, well, that describes the early days of gaming as well. Movies went from Train Arriving at a Station to The Great Train Robbery in twelve years and from the 15-minute Great Train Robbery to the maximum-opus Birth of a Nation in seven. Gaming started with Pong and Pac-Man in the 70s and got to Doom in the 90s, then Half-Life a mere four years later. If Half-Life is the Birth of a Nation of gaming, that means that the Gone With the Wind of gaming is still in our future, and the Godfather of gaming as well.

Young screenwriters take note: you may be working for the wrong medium. Apply your storytelling skills effectively to the medium of gaming and the world will appear at your doorstep.

As for me, my gaming education pretty much ends here. I’ve played the staggering Half-Life 2 and Doom 3 and Quake 4, but I don’t own an Xbox or Playstation or even a Gameboy. I suppose as my children age that situation will change. I invite my gaming readers to educate me in my future choices.

Spielberg: The Color Purple

WHAT DOES THE PROTAGONIST WANT? Celie, the impoverished, helpless protagonist of The Color Purple, begins the narrative by having her child is stolen from her by a cruel, oppressive man. By the end of Act I, her sister is driven away from her by a different cruel, oppressive man. Celie, like the protagonist of The Sugarland Express (and hardly alone in the Spielberg canon), wants her family reunited. Unlike the protagonist of The Sugarland Express, Celie is not only reactive, she is oppressed, beaten down, fearful. She can’t even open her keeper’s mail box, much less leave home in pursuit of her lost family.

The structure of The Color Purple goes something like this:

ACT I (0:00-28:30): This act could be called “Celie’s Family Torn Asunder.” Celie’s child is taken from her (and we hear of an earlier child who was similarly taken), she is traded by her father to a local farmer, who beats her mercilessly and treats her like dirt. Her sister Nettie runs away from home, away from her and Celie’s father, to be with her. The farmer, “Mister,” sets his eyes on Nettie, but when he attacks her she retaliates, and he drives her from the house. She leaves, reluctantly, promising that nothing but death can keep her and Celie apart.

ACT II (28:30-45:30): Many years pass. Celie grows from girl to woman. Mister’s son Harpo brings home a woman named Sophia. Sophia stands in contrast to both Celie and Nettie. She’s bossy, proud, short-tempered and unbendable. Celie, seeing an opportunity to get back at her tormentors, sparks a conflict between Sophia and Harpo. Her plan backfires and Sophia leaves Mister’s farm.

ACT III (45:30-1:24:00) Shug Avery, a colorful blues singer and an old flame of Mister’s, comes to stay on Mister’s farm. Shug, like Sophia, also stands in contrast to Celie. She is both weaker, in that she is drawn to men’s power, but also stronger, as she seems to move independently of them and has learned to use them to her advantage. Both Mister and Celie are obsessed with Shug. Shug initially calls Celie ugly and laughs in her face, but as she gets better (it’s not explained why she’s ill, but some sort of substance abuse seems likely) and gets back into singing (at Harpo’s backwoods juke-joint) she warms to Celie, writes and sings a song for her and even makes love to her. Shug then tries to enter the local church, but is rebuffed by the minister. She leaves Mister’s farm. Celie tries to go with her but loses her nerve. This is Celie’s low-point.

ACT IV (1:24:00-2:07:00) Sophiamouths off to the wrong person and ends up pistol-whipped, jailed and turned into a servant to a white man’s idiot wife, Miss Millie. Shug returns, now married to a grinning showboater, Grady. Mister and Grady bond over their mutual lust for Shug while Shug goes to the mailbox and discovers a letter to Celie from her long-lost sister Nettie. While Mister is off drinking, Shug and Celie discover a whole cache of letters from Nettie, where she outlines her life as a missionary in Africa and tells Celie that her children are alive and well and living as Africans. Now that Celie knows that she has a family elsewhere, she leaves Mister and goes with Shug to Memphis. Sophia leaves Miss Millie and returns to her home.

ACT V (2:07:00-2:30:00) An act of forgiveness and reconciliation. In Celie’s absence, Mister’s farm devolves into chaos as he staggers around in an alcohol-induced haze. Celie’s father dies, whereupon she learns that her father was actually her step-father and her real father has left her the family house. Now an empowered, independent landowner, Celie opens a pants-making business and prospers. Shug returns and takes up singing at Harpo’s again, but then repents and leads a crowd of sinners to the local church, where we learn that the minister is also Shug’s father. Meanwhile, Mister, having bottomed out, turns over a new leaf and secretly helps Nettie return to the US. Celie is reunited with her sister and her children.

NOTES: Spielberg, obviously chafing at the limitations of genre, steps way outside his comfort zone with this, his most complex narrative yet. The Color Purple has a protagonist who is frustrated in her desires and incapable of action until well past the two-hour mark. When her want is rewarded it is without her direct action. There is something Dickensian about the narrative, a life-spanning story of the poor and helpless suffering at the hands of brutal oppressors. But there is also something Capra-esque about it; Celie reminds me a lot of George Bailey, who longs to get out of his small town but is tied there by family obligations. George wants to get away in spite of his family, Celie wants to get away to find her family, both are stuck, both are incapable of action, and both are rewarded in the end in spite of their inability to leave town.

There is also something Capra-esque about Spielberg’s direction. As with It’s a Wonderful Life, The Color Purple is a story of extreme sadness and frustrated desire, yet the direction of each emphasizes the warmth and comedy of the narrative instead of the bleakness and despair. The performances in The Color Purple are sometimes startlingly broad — some of the scenes would absolutely not look out of place in 1941. Spielberg’s typically fluid, seamless direction doesn’t feel like it matches the material and leads to hyperbole and cartoonishness. Everything is overdone — Harpo isn’t just a poor carpenter, he’s a bumbling oaf who repeatedly falls through rooftops. His juke-joint doesn’t merely leak in the rain, it becomes a veritable indoor shower. Miss Millie isn’t merely a poor driver, she’s a caricature of a hysterical, swerving madwoman. Mister’s farm doesn’t just fall into ruin, he ends up with goats in the kitchen and shutters falling off the windows on cue. Shug doesn’t merely refuse a poorly-cooked breakfast, she hurls it across the hallway so that it leaves primary-colored splatters on the wall.

When the scenes don’t move as broad comedy they move as suspense — there are several sequences that would fit comfortably into Hitchcock. What the scenes do not work as is moments of genuine human interaction, which feels like a loss to me — the action feels like it’s all choreographed for the camera instead of the camera happening to witness moments of spontaneous behavior. Which is to say, I feel like Spielberg took a bold step forward by choosing this very non-genre narrative to shoot, but then shot it as though it were a genre piece anyway, relying on his sense of rhythm and his ability to manufacture suspense and emotional involvement to propel his largely plotless story forward.

Spielberg softens the brutality of the narrative in other ways as well. The antagonists of The Color Purple are all foolish, stumbling blowhards. Mister is a threat to Celie, but we never feel like he’s a threat to us — we can see he’s a petty tyrant easily bested. Likewise, Mister’s father is a muttering old codger and Miss Millie is a squealing, bug-eyed idiot. This helps us forgive them and aids Act V’s motions of reconciliation (which are not in the book), but it robs the story of drama. How effective an antagonist would Mr. Potter be in It’s a Wonderful Life if, at the end of the movie, it turned out that he was the one who brought Harry Bailey home and donated the money to get George out of debt?

The more I think of it, I’m not at all sure what to make of Act V of The Color Purple. Mister redeems himself, but does not announce it. Celie finds out that the man who raped her as a child was not her father but her stepfather, and Shug Avery begs for forgiveness from her own estranged father. After two hours of telling us about the horrors visited upon women by men, it’s like the story, in the end, pulls its punch — Mister isn’t so bad after all, Celie’s father is not only innocent but a benefactor, and Shug is all too desperate for the approval not only of her father but of the patriarchal church he represents. None of this is motivated by plot — it just sort of happens out of the blue. Celie even seems baffled herself: she accepts her father’s house but tells the previous owner she still doesn’t understand how she got it. The previous owner’s explanation doesn’t help very much.

It’s well known that The Color Purple is the only Spielberg movie that is not scored by John Williams, and yet I’d be hard-pressed to tell you how what Quincy Jones does here is very different from what Williams would have done. There is a lot of musical heartstring-tugging, and a good deal of Mickey-Mousing as well. Which is a shame, because there is a little shadow-movie within The Color Purple that is related to O Brother, Where Art Thou, a movie about the history of southern black American music that could have been fascinating. (The Color Purple is now, of course, a musical, so I suppose it’s not too late.)

Seen on the street

These have been showing up in Santa Monica. First it was just a few signs here and there, now they’re everywhere.

Disneyland report ’08

My apologies to my readers who wait with bated breath for my analysis of The Color Purple. My son Sam (6) had a day off from school, and my daughter Kit (5) has a school that consists primarily of her being out of the house for four hours, so my wife and I decided to take them to Disneyland.

We got to the gate at 10:00 on the dot, ie at the exact same time as everyone else. It was surprisingly crowded, I thought, for a Monday morning in April. I have memories of going on a Tuesday afternoon in February of 1996 and the place was almost deserted — there were no lines for anything and I was able to see absolutely everything I wanted to, including the robot Abraham Lincoln, by late afternoon. At which point I shrugged and said “Well, I guess I’m kind of done with this place until I have a couple of kids.” Hence yesterday.

Sam was keen on seeing only two things — the Indiana Jones Adventure ride and Star Tours, the Star Wars-themed simulator ride. He was a little anxious about the rides themselves — he dislikes roller coasters — but he wanted very badly to visit the gift shops associated with the rides to gather props and costume pieces. Kit, on the other hand, likes the Teacups, and generally would be happy to spend the whole day in the pink section of the map.

(Sam had just attended a Star Wars themed birthday party over the weekend where Obi-Wan, Anakin, Boba Fett, Darth Vader and Darth Sidious had all shown up and done bits with the kids. Sam had worn his elaborate Darth Vader costume and is very much into dressing up, or “cosplay” as the older set refers to it.)

The Indiana Jones Adventure was the longest wait of the day — 50 minutes before we got on the ride — and Sam loved, loved, loved absolutely everything about it, right up until the point where he actually had to get into the oversize Jeep that takes you through the experience. I see his point — the wait for the ride is, by a long measure, the most elaborate, detailed and atmospheric I’ve ever experienced, and in the middle of Disneyland that’s saying a lot. There are caves, booby-traps, an ancient temple, a newsreel, period music and all sorts of mood-enhancing foofaraw to get visitors hyped on the experience. The ride itself is rattlingly, shudderingly violent in the way it whips you around in your seat and parades you past a host of scares, thrills and spectacles — far too much to absorb in one go-around — and Sam spent the three-minute experience clutching my arm, with his face buried in my elbow. He was very precise in his assessment of the experience; he didn’t mind the scares — he likes being scared — but he cannot abide the “jerking around.” Indeed, I would agree with him. The Indiana Jones Adventure is an incredible ride, but the violence inflicted on my physical body is considerable.

(I now wonder if Sam’s love of being scared and his disdain for being “jerked around” explains his love of Jurassic Park and his indifference toward E.T.)

While Sam was being terrified on the dark, violent, genuinely frightening Indiana Jones Adventure, Kit was being terrified on the sunny, cheesy, outdated Jungle Cruise, the benign, walk-through Tarzan Treehouse and the utterly laid-back Storybook Land Cruise. Kit, it should be noted, does not like getting scared.

After Indiana Jones, Sam wanted to proceed directly to Star Tours, but my wife and I had made the decision to not split up the day in boy/boy-girl/girl adventures, and we met up on Tom Sawyer Island, or, as it’s now known, “Pirate’s Lair.” The whole way, Sam was insistent almost to the point of complaining (Why can’t we do Star Tours and then meet Mom and Kit? Why do we have to go to the island? Why can’t Mom and Kit come to us? etc.), then, the second we got to the island, he saw there was a treehouse and a complex network of caves, bridges and shipwrecks and we didn’t see either kid for about two hours as they went exploring.

I was a little dismayed at the half-hearted conversion of Tom Sawyer Island into Pirate’s Lair. A lot of the structures are the same, with only tiny emendations to change the island from the Mississippi to the Caribbean. The treetrunk of the treehouse still has “Tom + Becky” carved in it and the island is littered with an utterly anachronistic Indian Village, a river raft, a moose and a derailed coal train. It’s almost as though the Disney folk were hedging their bets, worried that this whole “Pirate” fad will blow over at any time and they’ll have to change the island back to Twainland.

(On the way back from Pirate’s Lair we ran into Jack Sparrow, who, when addressed by that name by a park visitor, resentfully murmured “Captain Jack Sparrow,” in a completely convincing Depp-like drawl, his delivery pitched at a volume no one but me could actually hear. This forced me to realize, yet again, that for all its faults, Disneyland is a demon for details.)

(Oddly, this visit was, for me, one of discovery — almost every attraction we hit was brand-new to me, even though it had been sitting there in plain sight for 54 years.)

Once off Pirate’s Lair (highlight for adults — real baby ducks) Sam and I split off again to see Star Tours while Kit and Mom headed for the Teacups and the Disney Princess Fantasy Faire. The wait at Star Tours wasn’t very long, and as usual there’s plenty of atmosphere to soak up, but as the ride itself approached I began to get apprehensive on Sam’s behalf. Sam understands what a simulator is, but the signs warned that Star Tours is a “turbulent” ride — meaning, you get jerked around a lot. I tried to explain this to Sam, who was confident he’d be okay. In the case of Star Tours, he was willing to get jerked around since there was no actual forward motion involved. Somehow the combination of the two is the thing that sets him on edge.

In the end, Sam made it through a good portion of Star Tours with his eyes open, then enthusiastically made a beeline for the gift shop. He had been given a special Disney Allowance of $20 and spent it on a special Star Tours blaster rifle. When he found out there was a separate entrance to the shop, he said, rather in the manner of a man who has just realized he has been duped, “Wait a minute — you mean I could have made it to the gift shop without having to go on the ride?”

(A note on Star Tours: the signs out front mention that it’s a collaboration between Disney and Lucas, and the experience confirms that — and points out how uneasy a fit those two sensibilities are. Cool Lucas-type design sits right next to cloying, Disney-type design, with big-eyed wisecracking droids and production values that only help remind the guest that Star Wars is a very cool movie indeed, while The Black Hole is deeply uncool.)

Hard upon Star Tours was the Jedi Training Academy, held at the Tomorrowland Terrace, an interactive stage show where kids can train with lightsabers — provided they are picked from the crowd by the Jedi teaching the class. We got there early to get a good seat, and once the show started things got overwhelming very quickly. The actor playing the Jedi Master was convincing, dynamic and in complete control of his difficult situation — organizing, inspiring and directing a group of small children in a rather complicated game, with a dramatic arc, that had to be wrapped up in 30 minutes.

The process of selecting which children go up on stage was, we were told, up to the actor playing the Jedi Master, and Sam, for reasons still a little mysterious to me, didn’t want to press his case too emphatically. As the Jedi Master selected kids from the crowd, everyone else jumped up and down and screamed while Sam subtly raised his hand. I don’t know if it was his sense of manners, a fear of being chosen, or a belief in the justness of his cause that kept him from speaking up, but in the end he was chosen and took his place on stage. Each youngling was given a training robe and a “training lightsaber” (ie, a plastic toy just like the ones they have at home) and the class was then led through a series of sword-fighting moves. No sooner had they learned a simple five-step fight routine than Darth Vader showed up with Darth Maul to challenge the students to a fight.

The actors playing Vader and Maul were both very convincing, to the point where some of the kids started freaking out. There was no attempt to softpedal the villains’ scariness, and the actor playing Maul was particularly aggressive in his attack. When it came time to fight, some of the kids were overenthusiastic, others were terrified to the point of tears. Sam tried to take the whole thing seriously but found that it all went too fast. I also have the feeling that Sam’s emotions were clouded by the fact that he greatly prefers the dark side characters — if he could have, he would have joined Vader and taken over the galaxy.

In any case, Vader and Maul were defeated, the Stormtroopers were sent packing, and all the kids were pronounced Padawans, complete with diploma (but without the robes and lightsabers). The diploma, interestingly, includes a political message, reminding the child that the Force must only be used in defense, never to attack.

Sam and I headed toward Fantasyland to hook up with Mom and Kit, who were investigating the Alice in Wonderland ride, King Arthur’s Carrousel and the Princess Faire show. We stopped at Autopia, another ride I’d never been on, where Sam got to drive his own car. He was a little too short to reach the pedal, but once he got the hang of it he delighted in swerving back and forth, trying to crash into stuff. I said “So, wait — I thought you said you don’t like being jerked around,” to which Sam replied, giggling, “Yeah, but not when I’m the one doing the jerking.” So the issue, finally, is not the jerking but the lack of control.

We found Mom and Kit at the Once Upon A Time shop in Fantasyland, where Kit was purchasing a Minnie Mouse As Princess doll. I don’t know where Kit’s interest in Minnie Mouse comes from. I don’t know where any child’s interest in Minnie Mouse comes from. Or Mickey Mouse, for that matter. They are barely represented in Disney fare except on the most superficial level, faces on corporate product. As characters they barely register to me; they stand for nothing, personify no particular point of view. Who looks at them and feels a deep sense of identification?

The kids were still going strong at this point, but Mom and Dad were about to drop, so we headed to the Rancho del Zocalo, the Mexican place in Frontierland. The food was great, the line was short and there were plenty of places to sit, which is all one can ask of a Disney restaurant. It was a big improvement over the last Disneyland dining experience my family had, where it was so crowded in New Orleans Square that we had to eat our clam chowder while perched on a wall on a major thoroughfare.

At one point, Kit was handed a sheet of temporary tattoos by a cast member who happened by, and at another point was handed a pair of Tinkerbell pins by another (“one to keep, and one to give”). These encounters were random and unsolicited. And again, one can find plenty of things to complain about in Disneyland, but the way they’ve got the guest’s experience figured out sets them far apart from any other theme park I’ve ever experienced. I’ve been to great roller coaster parks like Cedar Point in Sandusky, Ohio, a park with no particular point of view, where guests are forced to wait for hours in the hot sun with nothing to do but stare at the people ahead of them in line. There’s always something to look at while in line at Disneyland and the longest lines are always engineered in interesting ways that help build anticipation for the experience instead of emphasizing the length of the wait. The time generally flies at Disneyland, and while the prices are steep, I can’t remember a time when I left feeling cheated. Add to that random encounters with movie characters who hand out free stuff to your kids and I’m sorry, for a parent it’s all pretty awesome. Yes I know, it’s a gesture designed by a behemoth corporation, intended solely to extract more money from the child’s parents, but I feel like that’s the society we live in, and if a corporation takes your money while teaching your children generosity and non-aggression, well, at least it’s something.

After dinner we happened upon the nearly deserted Sailing Ship Columbia, which was about six times more interesting than I expected it to be. It’s outfitted like a genuine eighteenth-century merchant vessel and it, improbably, actually succeeded in giving one a vague impression of what lifeat sea on a ship like this, for years at a time, might have been like.

Then we headed over to New Orleans Square, where there was no line for the Haunted Mansion. Kit had never been to the Haunted Mansion, and Sam has only been to it while it was re-dressed in Nightmare Before Christmas holiday mode, so we decided to go in. Sam was underwhelmed, I was delighted (it was better than I remember it and has been subtly improved over the years), Mom was slightly disappointed (she remembered it being not so dark). Kit, sadly, went in frightened and was reduced to whimpering apoplexy by the end.

To help Kit over her trauma, I took her for three or four (I lost count) rides on the no-line Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh ride. The Winnie-the-Pooh ride, like many of the younger-skewing experiences, is weirder, more disturbing and more psychedelic than one would imagine. But it did the trick and got Kit ready for the final events of the day, the Dumbo ride in Fantasyland and the Astro Orbiters in Tommorowland. The difference between the two rides, as far as I can tell, is that they revolve in opposite directions, and Dumbo is three minutes long, while the Astro Orbiters are only a minute and a half. Neither had lines worth worrying about, typical for the younger rides after sundown.

All in all, I think I saw more of the park than I have in any other single-day visit and didn’t even lay eyes on huge swaths of it.

Kit was asleep before we left the parking structure, Sam examined his Star Wars toys for a few minutes but was out before we got to the highway.

Record Store Day

As mcbrennan and The New York Times remind me, today is Record Store Day in the US.

I offer three anecdotes:

1. Back in the day, there used to be a whole district of radio-repair shops in lower Manhattan. It was a thriving district, but by the late 60s it was thriving with cranky old men who gathered in musty shops arguing about arcana. Then David Rockefeller got the idea to wipe the district off the face of the earth and put the World Trade Center there instead. Overnight, a dying, outmoded business disappeared, and the World Trade Center stood in that spot, triumphant and unmovable, 110 stories tall and proud, for, um, 28 years. Well, all things must pass, and pride goeth before a fall, and substitute “record stores” for “radio-repair” and “iTunes” for “World Trade Center” and maybe, perhaps, you won’t feel so bad about the passing of this particular dusty institution.

2. I have spent more time in used record stores than probably any other kind of store in my life. I have, literally, thousands of used-record-store stories, of which only three or so are of interest to anyone but me. Suffice to say, when I was a teenager, living in an unheated trailer in southern Illinois in March of 1980, literally starving to death, living on a 25-cent can of store-brand spaghetti a day and a 33-cent frozen chicken-pot-pie on Sundays, a friend sent me 20 dollars in a letter. Fifteen dollars of that 20 dollars I spent on food, five I spent on a copy of Elvis Costello’s Get Happy!!

3. When I moved to New York in the autumn of 1983, ground zero of my existence was Tower Records at Broadway and 4th St. Tower was a five-minute walk from St. Mark’s Place, which held Sounds, St. Mark’s Books, Venus Records and a few other choice used-record stores. My goal for being a New Yorker was to live within a block of Broadway and 4th St. I lived in New York for 22 years and by 1999 I achieved my goal, living in a loft at Broadway and Washington Place, finally within walking distance of all the places I considered the lifeblood of my creative imagination. Any given Tuesday afternoon I could be found making the trek from Tower to St. Mark’s to the Strand and back. Including Tuesday, September 11, 2001, upon which morning I watched the World Trade Center burn on my TV, 1.5 miles away from the site, then walk downstairs and head over to Tower. The sidewalks were filled with refugees fleeing the financial district and Tower was filled with sobbing, distraught New Yorkers watching the TV monitors. I took all this in, and then bought Bob Dylan’s “Love and Theft” and Leonard Cohen’s Ten New Songs and went back home.

Support your local record store today! I will be at Amoeba in Hollywood this evening. (And let me just note that it was only a couple of years ago that the opening of Amoeba, which is a great store, forced the closing of several worthy Hollywood used record stores. Plus ca change.

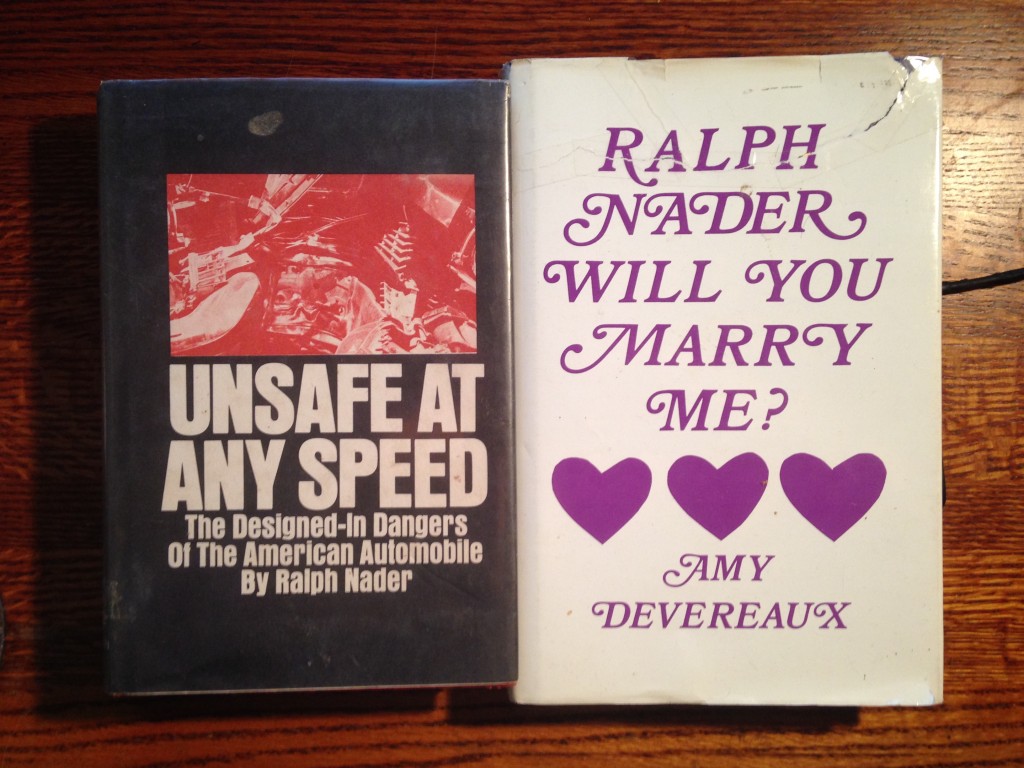

Literary Oddities: Ralph Nader, Will You Marry Me?

The first thing you notice about the book Ralph Nader, Will You Marry Me? is that its title is Ralph Nader, Will You Marry Me? If that is not enough of a stimulus to pick up a book, I don’t know what is.

Um, okay…

“The author has succeeded in placing herself in a totally vulnerable position where she is completely exposed. Actually at the end she surrenders because she is sick and tired of this war which has taken so much of her time and energy with no tangible results. Now that she is defeated, Amy Devereaux is wondering if Ralph Nader takes prisoners of war or if he shoots them on the spot. In either event, she says she will be happy to finally be at peace with herself and that will be her greatest victory.”

You assume at first that Ms. Devereaux’s wartime metaphor sprung from her writing this book during the Vietnam conflict, but no, it was published in 1988, long past Vietnam, and long past Nader’s glory days as a passionate consumer advocate for that matter.

The incoherence presents a different problem. You’re not sure exactly what the jacket blurb is getting at with this paragraph, except that the author of Ralph Nader, Will You Marry Me? is a bundle of raw nerves, ready to die if that what it takes, to — to — to what, exactly?

“This true story is about how foolish one can act when one is captivated by romantic love. Amy Devereaux is not a fictitious character and neither is Ralph Nader, but this story is really about her. Ralph Nader Will You Marry Me? follows the path that the author’s imagination takes writing letters, songs, poems, and a musical play to her hero. The actual contact that she makes with the real man misses her mark. Afraid to find out what he is really like, she avoids the opportunities she is given to confront him in person.”

Um, so, okay. The grammar is a little off but the message seems clear enough. Ms. Devereaux, it seems, is genuinely in love with, um, with Ralph Nader, and has actually written a book about her love for him. A 165-page-long book. One that includes the aforementioned letters, songs, poems, and, yes, a musical play, which the Table of Contents tells us is entitled Passionate Purple to Ralph Nader, a musical play.

“Confessing her failing, the author hopes to become free of it. In a way the story does not have an end because Ralph Nader and Amy Devereaux do not meet again inside the pages of this book. Will they ever meet? Will Amy and Ralph marry someone else? The answers to these questions remain unknown. Perhaps they will be answered in a prologue to the next edition of her next book.”

Yes, perhaps they will.

In the meantime, you’re still scratching your head. The prose of the jacket flap is not encouraging, but it’s still not entirely clear whether Ms. Devereaux means this book to be tongue-in-cheek, or, or — well, the alternative is that she’s written a book-length marriage proposal to Ralph Nader, and that’s just too weird to contemplate.

Luckily, this copy comes with a press release tucked inside the front cover, from the desk of one Mary Ann Belyea, Ms. Devereaux’s public-relations representative. The press release is four pages long and describes Devereaux’s many attempts to gain Nader’s attention. “During her 12-year romantic pursuit of her dream hero, Devereaux has directed hundreds of letters, gifts, packages and poems to Nader’s Washington office…None of her letters have been returned; none have been answered.”

It goes on: “Nader’s obvious disregard for her pleas for attention have not deterred Devereaux from her pursuit. Nor did it stop her from visiting his office, confronting him in the hallway to sing a solar energy song she had written, and later intruding on a conference to hand him birthday gifts. Even after his angry dismissal that day, Devereaux continued to bombard the consumer advocate with her pleas, devising elaborate schemes to make contact with him, even composing a ‘contract’ for his signature, promising that if they met she would never divulge their conversation. The contract went unanswered, too.”

You can’t imagine what Nader was thinking. A woman accosts him in the hall, sings him an unsolicited song on the subject of solar energy, interrupts a conference to bring him birthday gifts and sends him a contract for a personal conversation — what’s not to like?

The press release — my God, you exclaim, this is a press release! That means she wants people to know these things! — continues to discuss how Devereaux’s obsession with Nader has “caused her to reject other men with whom she might have had meaningful relationships,” and adds, “[Devereaux] sometimes fantasizes that the book…’will get Ralph’s attention, we’ll meet and he will marry me.'”

Well naturally — if you want a man to marry you, what would persuade him to do so better than a book-length marriage proposal?

We also learn that Ms. Devereaux is “a graduate of Arica Institute, est, Insight Transformational Trainings, Silva Mind Control, Adventures in Attitudes, and Peace Theological Seminary classes…and is a minister in the Movement of Spiritual Inner Awareness.” You know, you say, if you ask me, the only thing more convincing than graduating from a crackpot self-help program is graduating from six.

What is wrong with this Nader guy? How could he let a catch like this get away? The press release concludes with an itinerary for Ms. Devereaux’s five-city book tour.

And all of that is before you even open the book.

The introduction begins “I wrote this book attempting to convince Ralph Nader that my love for him is sincere and that I have the ability to fulfill my promises. It will be impossible for Ralph to deny my reality and for me to continue my fantasy once we face the truth together, whatever that is.”

Well, exactly.

“Once RALPH NADER WILL YOU MARRY ME? is in print and widely publicized, I can no longer rationalize Ralph’s silence by telling myself that he has been sheltered from knowing about my existence and my letters by his staff. I do not want to spend the rest of my life in a dream world, like Cervante’s [sic] Don Quixote tilting at windmills. I want to be loved on earth as well as in heaven.”

Well, that answers your question — she is sincere, she loves Ralph Nader, and she’s written a book to get his attention. Singing to him in the hallway didn’t do it, delivering a birthday present to him during a conference didn’t do it, deluging his office with hundreds of letters, gifts, packages and poems didn’t do it, well, god damn it, this book will do it. It has to.

The book proper consists of letters, poems, song lyrics, personal reminisces, a little autobiography, and yes, a musical play. The play begins with a character named AMY entering the offices of a character named RALPH, who is apparently some kind of important consumer advocate. Ralph is reluctant to meet Amy at first, and indeed shows signs of fear and desperation when he hears she has entered his offices. Eventually he realizes what a unique, impressive person she is, and views on solar energy are discussed. There are many love duets.

Sample lyric:

AMY: YES, I REALLY LOVE YOU, RALPH, AS I LOVE MYSELF.

RALPH: WILL YOU HELP ME WITH MY WORK AS WELL AS IRON MY SHIRTS?

AMY: I WILL WORK AS HARD AS YOU, BUT IRONING MAKES ME BLUE.

RALPH: WHAT WILL YOU DO AS MY WIFE, WHEN YOU SHARE MY LIFE?

AMY: I WILL COOK AND CLEAN OUR HOUSE, JUST DON’T BE A LOUSE.

Sample dialogue:

RALPH. Amy. I’m so grateful that I didn’t write you off as crazy. You are crazy. You know that, but blissfully so. Your craziness did save me, as you intended it to.

AMY. I did want to save you, but I didn’t know what from.

RALPH. From my false self, the part which is always so serious, the part which bores people. Would you like to dance?

AMY. Yes, I would.

Sample stage direction:

(Ralph lifts Amy into his arms and carries her into his bedroom where he lays her gently on his bed. Ralph lights a candle by the bed and turns out the rest of the lights.)

The play ends, as all romantic comedies must, with a wedding. No points for guessing who gets married.

The book also includes a short story, “Maria’s Farewell,” which does not seem to be directly related to the author’s pursuit of Ralph Nader, and is apparently inserted here to show that Ms. Devereaux is capable of writing something other than book-length marriage proposals to Ralph Nader.

It ends with this personal message to Nader: “Taking the personal, emotional, and financial risks I have by exposing myself to the public and to you, unprotected as I am, is the final demonstration of my love for you, short of personal contact which depends on your cooperation. I can do no more. It is up to you. Will you accept my love or reject it? That is the question, just like Shakespeare’s ‘To be or not to be.’ Will you be with me? Ralph Nader, will you marry me?”

From the Introduction: “I wanted Ralph’s fans to know that he is loved by an intelligent, sensitive, loving, attractive, single woman. The fact that he has remained unmarried up until now is not the result of his being unloved or unlovable.” Tell that to the Democrats of 2000.

Google does not divulge the existence of Initiation Publications, nor that of Mary Ann Belyea Public Relations. However, apparently Ms. Devereaux is still very much around, creating art, which I am pleased to report is not bad at all, and can be viewed here.

eBay item of the week: the recordings of Leonard Nimoy

The great interpretive singer Leonard Nimoy exploded upon the popular-music scene with his first album, the curiously-titled Mr. Spock’s Music From Outer Space (1967). Still an unknown quantity, he nevertheless took a daring stance and adopted a distinct, recognizable “persona” for his performances, an alien space man named “Mr. Spock.” This interpretive strategy, designed to create an air of mystique around the singer, was at the same time being adopted by The Beatles, who copied Nimoy for their groundbreaking work Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Much later, David Bowie would grab this idea and run with it all the way to the bank, but it should be noted that Nimoy did it first.

The song titles on Mr. Spock are intriguing and otherworldly: “Theme from Star Trek,” “Music to Watch Space Girls By”, “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Earth” and the immortal “Visit to a Sad Planet.” The album caught the “space” craze of the mid-sixties, was a huge hit and Nimoy’s label, Dot Records, was soon clamoring for more.

The “Mr. Spock” persona had made Nimoy a household word among lovers of song, and Nimoy was under great pressure from his label to deliver more of the same. But Nimoy, a formidable artist with incredible powers of persuasion, already felt that he had “done” the Mr. Spock thing. Like Dylan, Nimoy is an ever-changing chameleon who cannot be constrained by the demands of the marketplace. But commercial pressure at the time was intense, and Nimoy was forced to create at least half an album with the “Mr. Spock” persona intact.

The result of all this conflict was 1968’s Two Sides of Leonard Nimoy, a bifurcated whatsit that, in the hands of a lesser artist, would have stank of bitter compromise. Instead, it is a blazing triumph and perhaps Nimoy’s masterpiece. It was 1968, there were riots in the streets, change was in the air, and Nimoy was right in the middle of it. “Mr. Spock” handles Side 1, singing “Highly Illogical,” a stinging rebuke of the entire human race on the level of “Desolation Row” or “Sympathy for the Devil.” Later he sings “Spock Thoughts,” practically a philosophical treatise in song. The side closes with “Amphibious Assault,” which the liner notes describes thusly: “A surrealistic battle of the future. Will war come to this?”

On the “Leonard Nimoy” side, the mask comes off and the warm, tender humanism of Nimoy bursts through. The results are intoxicating as he sings “Bilbo Baggins,” a jocular celebration of “the bravest little Hobbit of them all,” Glenn Campbell’s “Gentle on My Mind” and Tim Hardin’s “If I Were a Carpenter.” No elitist, Nimoy closes the album with the touching parable “Love of the Common People.”

Obviously chafing from the compromise of Two Sides, Nimoy ditched the “Mr. Spock” persona once and for all with 1968’s The Way I Feel. Creating a soft pocket of sensitive peace amid a world gone crazy and turned upside-down, this album of delightful love songs and quirky portraits is a small triumph on the level of Dylan’s John Wesley Harding. The titles say it all: “I’d Love Making Love To You,” “Please Don’t Try to Change My Mind” and Joni Mitchell’s poignant “Both Sides Now” — this is an album of love and its consequences. But social commentary also raises its triumphant head; the LP’s highlight is “If I Had a Hammer,” not to be confused with Two Sides’ “If I Were a Carpenter.” Intended as a “little”, transitional album, The Way I Feel was a huge hit, its sales bigger than those of Nimoy’s first two albums combined, and Dot, ever the raging capitalists, demanded more of the same. This time, luckily for the music world, Nimoy was happy to comply.

Who would not want to feel The Touch of Leonard Nimoy? Almost a sequel to Feel, 1969’s Touch expands upon that album’s greatest themes and then goes further, including Randy Newman’s “I Think It’s Going to Rain Today” and the jazz standard “Nature Boy.” Nimoy then, unexpectedly, brilliantly, brings his career full circle with “Contact,” a song about contact with aliens.

No one knew it at the time, but Nimoy was, in fact, saying good bye with the inclusion of a “Spock”-themed song on the otherwise tender Touch. He abruptly withdrew from the marketplace of song, retired to his mountain retreat in Massachusetts and has since disappeared. The Salinger of Song, he has not issued an album of new material in almost 40 years. Why this happened is one of the great mysteries of popular music. Maybe the pressures of the pop-star world proved to be too much for this sensitive artist, maybe he’d decided he’d had enough, or maybe he felt he’d said everything there was to be said. Who knows? But we have these albums and that is treasure enough.

Sensitive to the demands of a marketplace starved for greatness, the prestigious label Famous Twinsets released a two-LP set of choice cuts called Outer Space/Inner Mind. For a new generation of listeners, this was a gold mine of delight. Strangely, Famous Twinsets didn’t think to put a photo of Nimoy on the cover, instead focusing the packaging on the model spaceship the “Mr. Spock” character is shown fondling on Nimoy’s first album. I guess they were trying to preserve the mystique of their reclusive star, or perhaps Nimoy demanded that his picture not be used in order that he be able to move through the world unrecognized. We may never know. In any case, Outer/Inner provides an excellent overview of this vital artist, even though it does, for some inexplicable reason, completely ignore songs from Touch.

DID YOU KNOW? Nimoy has also worked as an actor.

Spielberg: Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom part 2

So. Moving on:

Chapter 1 (1:00:00-1:10:00) This gripping little reel involves Indy and his family stumbling upon an obscene, terrifying blood-cult ceremony. I myself have never stumbled across an obscene, terrifying blood-cult ceremony so I don’t honestly know if the one depicted here is accurate or not, but I’m going to go ahead and say that for members of blood cults I’m guessing that this sequence is probably pretty cheesy. I mean, lava? Who has lava at their blood-cult ceremony? That’s just stupid.

For the rest of us though, it’s pretty freakin’ dark. The design of the temple, the human skins fluttering in the breeze, the high priest wearing an animal skull on his head, the swaying, groveling celebrants, the sacrificial victim getting his heart ripped out and surviving, it’s all perfectly stupid and utterly intoxicating. Spielberg is a master at taking an assignment and running with it — “Oh, it’s a weird, scary blood-cult ceremony? Well then, let’s make it the weirdest, scariest ever.”

One flaw: we meet our head villain, cult priest Mola Ram, an hour into the movie, and they don’t even tell us he’s the head villain, we just kind of have to figure it out after a while. Plus he’s wearing a weird costume and is hellishly lit — it’s a great entrance, but would have been more effective an hour earlier — you know, like at the point where the head villain of Raiders showed up. Is there some reason Mola Ram couldn’t be one of the guests at the Maharajah’s dinner table? Or for that matter, why couldn’t he be the Prime Minister? The PM is, we eventually learn, one of the cultists, why not make him the head priest?

(I do have one problem with the cult ceremony. The victim has his still-beating heart removed from his body, which is really cool. But then, when Willie is the victim, Mola Ram doesn’t bother ripping out her heart, which is good for Willie, but pulls the villain’s punch. Better, I think, to forgo the cool effect of the first victim’s heart being ripped out than to make it look like the villain is “just kidding” later on in the act. But then, I get the feeling that the architecture of the sacrifice ritual is based on Mola Ram holding the still-beating heart as it bursts into flames. I get the feeling this image came into Spielberg’s head before anything else and he structured the whole ceremony around it.)

Funny thing is, as implausible as the plot of Temple is, Mola Ram is a great villain and his plan, in its weird, twisted way, makes sense. He’s got a solid motive, a decent plan and a logical endgame. This puts him ahead of 80% of Bond villains and even ahead of Belloq, who had huge balls on him to think he could wrest control of the Ark of the Covenant while in the employ of Adolf Hitler, but had no plan for what he was going to do once the Ark was opened.

(That is, Belloq thinks the Ark is a transmitter to God, and that by opening the Ark before handing it over to Hitler will give him the power that Hitler craves. But he doesn’t know what “transmitter to God” actually means, a bit of shortsightedness that turns out to be disastrous. “Hmm, my head is exploding — maybe I should put the lid back on this thing and think this plan through a little more.”)

After the ceremony, the temple immediately empties and Indy goes after the Sankara Stones. Two things: hey, wait, wasn’t this temple just filled with hundreds of zombie celebrants? How did they get out so fast? And doesn’t anybody stay to, you know, clean up? Not a single altar-boy or acolyte to be seen. And, I notice that Indy treats the Temple of Doom with ten times the respect he shows to either the Well of Souls or the Peruvian temple in Raiders — he tiptoes carefully through the rafters, cautious not to upset anything. Well, come to think of it, this isn’t an ancient temple, it’s practically brand new — what’s the point of wrecking it?

In any case, Indy nabs the stones, but as he is heading out of the temple, he discovers the mine, being operated by the kidnapped village children and the movie, in case it wasn’t dark enough yet, takes an even darker turn.

Chapter 2 (1:10:00-1:17:00) Indy might be a fortune hunter, but he can’t just turn his back on a mine full of enslaved children, but before he can do much for them he and his family are nabbed by the bad guys. Indy is tied up, Short Round is whipped, Willie is spirited away somewhere (odd that Spielberg lingers on showing us children being whipped, but shies from showing what might have happened to Willie). Indy is poisoned for the second time in the movie, forced to drink the blood of the whatever. And for some reason the boy Maharajah is on hand with a voodoo doll. What? A voodoo doll? Either Spielberg is just throwing in any creepy thing he can think of at this point, or else the young Maharajah was educated in, um, Haiti? I can imagine a Kali-worshiper watching this scene and finally throwing up his hands and saying “Okay, forget it, I was with this movie up to this point, but voodoo? That’s just insulting.”

In any case, the scene is almost unwatchably brutal and intense, which is great because it is, wouldn’t you know it, another expository scene, where the head villain explains his plot to the protagonist, and we don’t even notice because it’s just so unspeakably ghastly. And yet the movie still hasn’t gotten as dark as it’s going to. Because the next thing you know, there is, yes, another blood-cult ceremony, this time with Willie as the sacrifice and Indy as the priest.

Chapter 3 (1:17:00-1:27:30) Hey, wait a minute! These Kali-worshipers just had a ceremony, like, ten minutes ago! And now they’re having another one! How many of these ceremonies do they have in a day? How are the worshipers supposed to get anything done? What is the rest of their day like? I have this image in my head of a bunch of Kali worshipers getting back to their office jobs after changing out of their Kali-worshiping duds, and they’re filing papers and entering data and playing Minesweeper, and then suddenly one of their co-workers comes along and says “Hey guys! They’re doing a second sacrifice today! Everybody back to the Temple!” and everybody kind of looking at each other like “Hey, you know, Kali is great and all, but I have a life, dude.“

Speaking of which, if Mola Ram has a congregation of zombies that are able to drop whatever they’re doing at a moment’s notice to come attend a sacrifice, why doesn’t he use them to help dig for diamonds? Surely they’d be more efficient than child slaves.

Anyway, so Indy is now bad and Willie is now his sacrificial victim. And I suppose there may be a metaphor at work here — if Willie represents the cynical, greedy side of Indy, and Indy himself has now been boiled down to a “true believer,” then there could be a comment in here about the bad side of pure faith.

But something tells me that it’s really just “plot.” I suspect this because, fact is, the rest of the movie from here on out is pretty much just plot. This is a good thing. Movies need plot, and few directors understand plot better than Spielberg, and, as any screenwriter will tell you, plot is hard. In fact, I’m going to go ahead and say that Temple of Doom is probably the most tightly plotted movie in Spielberg’s filmography, which is the reason I find it so compulsively watchable.

Oh, and the action/suspense elements of all this are just masterfully presented. The roasting cage bobbing up and down with Willie inside, Indy backhanding Short Round, the fight on the altar, it’s all just incredible.

Anyway, Short Round cures Indy (that is, the son cures the father, a plot turn I attribute to George Lucas, since he made six movies revolving around the idea), driving us into —

ACT IV (1:27:30-1:54) Here we have another textbook ur-Dreamworks “race to the finish line” final act, a breathless sequence of stupefying, expertly-mounted set pieces, each topping the last.

Chapter 1 (1:27:30-1:35) We begin with the massive slugfest in the mine, as Indy and his family free the enslaved children and beat the crap out of their captors. The chapter climaxes with Indy’s fight with the Enormous Thuggee atop the Rock-Smashing Machine.

Chapter 2 (1:35-1:43) We go straight from the stupefying slugfest into the stupefying mine-car chase, a sequence so mind-bogglingly complex I cannot even begin to imagine how it was planned, much less shot. The chapter ends with a literal cliffhanger, as Indy and his family are left, yes, hanging from a literal cliff as torrents of water blast out of the mine entrance.

(Of course if I slow down long enough to ponder the design of this ridiculous mine, which apparently is inside an active volcano, the whole thing seems kind of silly.)

Chapter 3 (1:43-1:54) The cliffside scene bleeds into the bridge scene, and at this point I’d like to pause to break the fourth wall and tell a personal anecdote:

When I was at Dreamworks working on Antz, I had an idea for a scene that took place on a high, narrow bridge. As it happened, Spielberg was in the room during the pitch meeting and so I pitched the scene and added “you know, like the end of Temple of Doom,” at which point Spielberg closed his eyes like he had a headache and said, with no small amount of anguish, “I hated that scene.” And I could barely think of what I was supposed to say next about my own project, because all I wanted to say was “What? You hated that scene? But, but — you’re Steven Spielberg! And when you shot Temple of Doom you were at the peak of your powers! What power could have compelled you to shoot a scene you hated that much?” This moment bothered me for years, rolling around in my head — how, why, would Spielberg shoot a scene he hated? I breathed a sigh of relief when I saw the “making of” DVD and the mystery was solved: Spielberg explains that while shooting Temple of Doom he found out, too late, that he has a fear of heights. This fear kept him from shooting the bridge scene the way he had planned (he literally could not make it more than a third of the way out onto the bridge without breaking out in a cold sweat) and he spent the entire shooting of the sequence in a state of physical discomfort. Needless to say, the bridge scene did not make into the script for Antz.

End of personal anecdote.

Anyway, I think the bridge sequence comes off well enough — the shot of Indy realizing the extremity of his dilemma is probably my favorite of the character, and the action of the climb back up to the cliffside is, again, expertly handled. Although of course I would love to know what Spielberg had intended for the scene to begin with. I imagine the cuts to the alligators below could have been more gracefully integrated — I never believe that anyone is ever actually eaten by an alligator, although it would serve the people right for all the disgusting things that get eaten in this movie — but otherwise I think it all works fine.

Once Indy gets Mola Ram in his sights, he snarls “Prepare to meet Kali — in Hell!” And I just can’t help but think “Jeez, what a lame threat.” Honestly, howis Mola Ram supposed to be scared by a guy who doesn’t even have a token understanding of his faith? Threatening Mola Ram with “prepare to meet Kali — in Hell!” is like threatening a rabbi with “Prepare to meet Jehovah — in Hades!” or threatening a Muslim with “Prepare to meet Mohammad — in Nirvana!” or threatening the Green Goblin with “Prepare to meet Spiderman — in Gotham City!” I want Mola Ram to look scared for a second and then pause and say “What? What the hell are you talking about? Why would Kali be in Hell? Who are you?” And then Indy would have to do some hasty backpedaling: “Well, you know what I mean, I mean, you know, whatever bad-place afterworld you guys have — I’m sorry, I haven’t studied Kali blood cults that much.” And then Mola Ram could say “Why not just say ‘Prepare to meet Kali?’ You had me up to that point, my heart was really racing, but then you had to add “in Hell” and all I could think was “Christ, what a douche.”

Indy’s complete ignorance of Mola Ram’s faith is confusing since, mere seconds later, he knows just the magic words that will make the magic rocks ignite into flames. “You betrayed Shiva!” he growls, then helpfully translates the phrase into, I’m guessing, Hindi. Because, apparently, Shiva, up to this point, was unaware that Mola Ram had acquired the Sankara Stones and was using them to amass a power base for himself on Earth. No, it took Indiana Jones pointing that out before Shiva, wherever Shiva hangs out, to look up and say “What’s that? Mola Ram betrayed me? Well, I’ll settle his hash, you just watch! Gimme my rocks back!”

(As with the Ark in Raiders, Indy, the non-believer, is spared the wrath of the god-of-the-moment and allowed to make off with the magic artifact. There is a message in there somewhere.)

The young Maharajah, now transformed into a good colonialist, leads Capt Blumburtt and his troops to the bridge to help save the day. And I can’t help but wonder if that’s necessarily a good thing. There is a troubling thread of colonialism running through all the Indiana Jones movies (and all of George Lucas’s movies too for that matter) but Spielberg breezes past the moment without comment, even though its perfectly obvious that, if not for people like Capt Blumburtt, there wouldn’t be people like Mola Ram in the first place.

(As Walter Sobchak might say, “Say what you want about the tenets of the Kali Ma, at least it’s an ethos.”)

Spielberg: Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom part 1

Like Raiders of the Lost Ark, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom has four acts, each lasting about 30 minutes. Each of the acts has three distinct chapters, giving us a twelve-chapter serial drama.

What’s different, structurally, is that Raiders has a restless spirit, jetting (well, prop-planing) about all over the globe, from Peru to the US to Nepal to Cairo to Secret Sub Base Island. Temple gets all the travel out of the way in the first 25 minutes and spends the rest of its time in more or less one place, and an hour of that in one location, underground in a cave. The result is a much differently-shaped narrative than Raiders, one that’s spirited and frantic for the first act, then claustrophobic and inward for the rest of the movie, and dark, dark, dark. It gives us twenty minutes of breathless forward movement, seventy minutes of horror and torture, then thirty minutes of blasting escape.

The movie is often criticized for its unpleasantness and weirdness, as well as its generally heavy attitude, but I find it as compulsively watchable as any of the best of Spielberg and a much meatier experience than either Raiders or Crusade.