cartoonist of the day: Mark Gleim

Mark Gleim’s A Simple Apology is good. The drawing, as you can see, could not be simpler, but is deceptively so. But I’m impressed by the sheer number of left turns he manages to put into his strips.

Some thoughts on the anniversary of Katrina

Of all the horrifying images of Katrina, the one above is the one that sticks with me most. Bush, in the photo, is flying over New Orleans surveying the flood damage. He has turned to the camera to give what he thinks is his best “heavy is the crown” face, but all I can see in his expression is “can I go home now?” “I’ve flown over the destroyed city, I’ve looked out the window, I’ve ‘shown I care,’ can I go home now and get back to killing people, spying on Americans, crushing dissent, gutting the constitution and making all my friends wealthy?”

Katrina, for me, was when the mask finally came all the way off, revealing the administration of Bush II for what it was: an unfathomably brutal, cynical, uncaring cabal of monsters concerned only about accruing wealth and power. Karl Rove spoke often of building a “permanent Republican majority,” but time has shown that the Bush II people (who, let’s face it, are also the Bush I people, the Reagan people, the Nixon people) don’t even care about their party — they care only about themselves. They act as though they are the last people who will ever preside over the government of the United States. They believe this whole system of government was set up for them to loot the treasury for eight years and then leave town chortling.

But I was talking about Katrina.

First thing that happened two years ago today was that, for me anyway, the mainstream American news media became obsolete. The news out of New Orleans was coming too fast for outlets like the New York Times to keep up with, so I started looking elsewhere. News blogs like Eschaton, Crooks and Liars, Daily Kos and Americablog I had heard spoken of but never frequented, but during Katrina I sought them out because they were gathering information from all kinds of different places, giving me a much fuller, more truthful picture of what was going on on the ground than, say, CNN or Fox News were, including Anderson Cooper and Chuck Roberts and Geraldo and their efforts to convey the horrors of the flood.

I have not looked back since. I haven’t turned on the TV to watch an American news outlet since Katrina and I find that I am better informed for it. American TV news, it will surprise no one, is driven not by a search for journalistic truth but by advertising dollars. This formulation can only lead to networks promoting sensation over substance in their attempts to garner more viewers than their competition. The “liberal blogs,” I find, regardless of their openly-stated biases, to be more informative and ultimately more truthful than any money-driven corporate news organization.

The second thing that happened was that Katrina exposed America’s conservative movement for what it truly is. I saw a clip from The O’Reilly Factor where Bill O’Reilly, within days of the disaster, denounced the dead, the homeless and the doomed as lazy, shiftless losers who deserved exactly what they got. Now, I know that O’Reilly is a merely a heartless clown who believes in no ideology beyond the continued dominance of his little patch of media real estate, but I, who have seen a lot from these monsters in the past few years, was still struck by the sheer hatefulness of his response. I couldn’t find the clip on YouTube, but the quote I remember was O’Reilly saying something along the lines of “It is not the responsibility of the federal government to help the people of New Orleans, it was the responsibility of the people of New Orleans to get good jobs and good educations so that they would not have to live in poor neighborhoods below sea level.” His words were decidedly more snide and scabrous, but you get the idea.

Anyway, I got stuck on the first part of the statement and it rolled around in my head for days. It’s not the responsibility of the federal government to help the citizens of a major American city when it is struck by a natural disaster? I had heard a lot of denial of responsibility from conservatives over the previous five years, but this was a new one on me. If the federal government is not responsible for protecting its citizens, what, in God’s name, are they there for? Why should we pay federal taxes to a government who, literally, does not care if we live or die?

This concept bothered me so much that I went around reporting this to friends. One of those friends, not a poli-sci major but a regular, garden-variety college graduate, gave me a strange look, as though she suddenly realized that I was, in fact, only five years old, and said “But Todd, that’s the whole point of a conservative government — you give them all your money and they use it to fight wars forever.”

And so that weekend, not only Katrina but Iraq came into sharp focus for me. The Bush administration declared war on Iraq not because Iraq had weapons of mass destruction, or because they were linked to Al Qaeda, or because Saddam was a bad, bad man, but because it served their political ideal of always being at war so that nothing they do can be questioned and they can take all the money they want. I guess I always knew that on some level, but it took Katrina, and that quote from O’Reilly, and the above photograph to fully expose Bush and Cheney for what they are.

Because I realized, the reason Bush has that look on his face is because, for him, Katrina was not a disaster. When he told the lying, stupid, incompetent, crony head of FEMA he was doing “a heckuva job,” he wasn’t being clueless or idiotic, he was speaking honestly. Because for him, Katrina, far from being a disaster or tragedy of monumental, history-changing proportion, was the perfect fulfillment of his principles, namely, that in the perfect conservative world, the wealth of the nation is ever-concentrated upward from the poor to the middle class to the upper class to the ruling class, where it stays, and then the poor die, proving, by divine providence, that they were unfit to live in the first place. Bush, in his actions, said “I am your leader. Give me your money and then die, so that I and my friends in the military/industrial complex may flourish.” I remember one Republican politician surveying photos of the inundated 9th Ward and reasonably judging that “it looks like that could all just be bulldozed,” as though it was not actually a city, where thousands of people had homes, but simply another felicitous opportunity for gentrification for some lucky real-estate developer.

It was only when even Fox News was horrified by the scenes of unspeakable carnage and loss that Bush and company realized that they had to put on some kind of show of caring, which is exactly what they did — they put on a show. They put Bush in New Orleans, turned on the lights, put a camera on him, and as soon as he was off the air, turned off the lights again, and as far as I know, that’s the last time Bush ever thought about the destruction of New Orleans. Bush in that speech looked ridiculously uncomfortable and stiff, not because he was reeling from the loss of a major American city on his watch, but because he honestly had no idea what the hell it had to do with him.

UPDATE: Given the above, how appropriate it is that Bush chose the anniversary of Katrina to ask the American people for another $50 billion to continue his endless war in Iraq (which has, by the by, now killed more Iraqis in four years than Saddam Hussein managed to kill in thirty).

UPDATE UPDATE: Pam Spaulding of Americablog is on the ground in New Orleans today and efficiently outlines just how much caring has been done by the Bush administration on the behalf of the city.

The fault lies not in our stars

Stars: “I am not gay, I have never been gay.”

One of the major tenets of conservative thought, a perfectly legitimate one, is that people should be responsible for their own lives. And yet, one of the major tenets of the conservatives in Washington today is that nothing is their fault and they never do anything wrong, even when, especially when, there is overwhelming evidence that it is and they have. Pushing this example to its most absurd extreme, Senator Larry Craig (R-Idaho), a major opponent of gay-rights legislation, claims that an Idaho newspaper is to blame for his actions in a Minnesota airport men’s room.

How this works I’m not exactly sure. A newspaper devotes column space to trying to prove you’re gay, so you, understandably distracted and anxious about this crisis, proposition a cop in an airport men’s room? Then, when you’re arrested for this behavior, instead of saying “no, wait, this is all a misunderstanding, and it’s ironic that this has happened, because, oddly enough, there’s this newspaper in Idaho that keeps saying that I do things exactly like this all the time, and I’ve been very distracted and anxious about that,” instead of saying that, you say “I am guilty as charged and I hope this ends the matter.” Damn those Idaho newspapers! They get our highest elected officials into the most awkward situations! How do they do that?

Senator Craig

Crooks and Liars posts this video of Senator Larry Craig (R-Idaho) giving his statement regarding his arrest for and confession of propositioning an undercover cop in a Minnesota airport men’s room.

Aside from the obvious (yet another anti-gay Republican senator being revealed to be a closet case), I am interested in the piece for the senator’s opening remarks. He begins by saying “I’d like to thank you all for coming out today — ” and my pulse was momentarily raised by the possibility that he was then going to finish the sentence with ” — by doing the same myself.”

Alas, he didn’t. But that would certainly be something, would it not? Imagine if this were his statement instead of his blah-de-blah boilerplate, easily-dismissed denial (“denial” having multiple meanings here):

“You know, I’m glad this happened. I’m glad this happened, because it’s a perfect example of the kind of behavior people like me have been driven to by the repressive, inhumane laws that people like me have passed. Now that everyone knows I’m gay, that my personal life is a sham and that my professional life is a gigantic, brutal machine of self-hate, maybe now I can say “screw all that, I’m not going to be a politician any more, I’m going to finally try to make my life line up with the acts I spend my waking life performing, I can let my wife have some kind of normal existence for her remaining years, and I won’t have to proposition strange men in airport men’s rooms for my kicks. I’m 60, I’m fit, I’m rich, I’m ready for action — who wants me?”

Unless, of course, he’s afraid the answer would be “no one.”

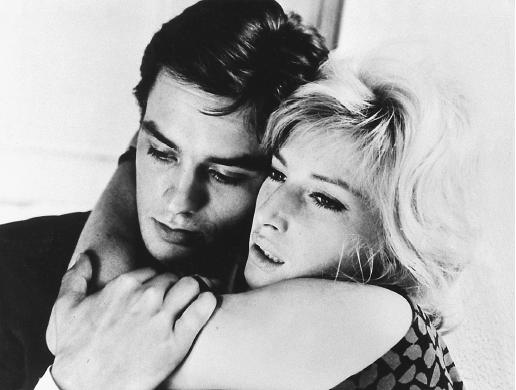

Movie Night With Urbaniak: L’Eclisse

YOUR ATTENTION, PLEASE: This post was originally at least twice as long. Somewhere in the posting of it, half of it got mysteriously eaten by some livejournal program glitch. This makes me angry, but I currently don’t have the time or energy to re-write it. Suffice to say, I liked this movie and so did

.

[beginning of original post]

You know how I mentioned last time around how L’Avventura has no plot, yet is still tremendously exciting? Well, L’Eclisse has even less plot than L’Avventura, and is even more exciting. It’s almost like Antonioni is daring himself to stretch this method of designing narratives as far as it will go.

[significant portion of post mysteriously eaten here.]

[description of first 50 minutes of the movie — Vittoria’s difficulty with relationships, her restlessness, her discomfort, her flight to Verona]

[we join the post half-way through — I am describing a rather amazing 10-minute scene set in the buzz and flurry of a bad day at the stock exchange]

Urbaniak says, “the best extra work of all time.” I mean, it’s really quite stunning, it’s a hugely complicated scene, certainly as complicated as, say, any Hitchcock suspense scene, and as exciting, but like I say, it’s even more of an impressive stunt because we have no idea what it has to do with anything.

Anyway, Vittoria’s mother is there at the stock market, as usual, but today she’s really upset because she’s losing all her money. The market takes a downturn and stays there and everyone is quite upset by the end of the day. And Vittoria shows up toward the end of the day, wondering what all the excitement’s about. She knows nothing about the market and less about crashes (“But if someone lost the money, then surely someone else had to get that money — right?” she asks, hopefully).

10. Piero points out to her a man who has lost 50 million lira in the day’s trading, a sad, overweight, bespectacled man who wanders silently out of the marketplace, and I say “it would be great if the movie now just suddenly dropped everything and followed that guy around,” which, much to my amazement, it then proceeds to do, for about five minutes. Vittoria follows him as wanders, a little shell-shocked, around Rome, much like we’ve watched Vittoria wander shell-shocked, only we know the reason for this guy’s discomfort. But it seems Vittoria sees a kindred spirit in this man who’s lost everything and doesn’t quite know how that happened. She tails him to a little cafe, where he sits down and busies himself with a pencil and paper. We think maybe he’s writing a suicide note or a letter of resignation, but when Vittoria (and we) finally see the paper, it’s covered with childish, even girlish, drawings of little flowers.

11. Vittoria takes Piero to her mother’s apartment for some reason, I don’t know why. She barely knows him, only that he’s her mother’s stockbroker (and her mother now owes him quite a lot of money). We see the room where Vittoria grew up and learn that her father died in the war and her mother is terrified of poverty. As is everyone, quips Piero, but Vittoria says that she never thinks about it. Or being rich either. And we realize that Vittoria doesn’t seem to have given much thought to anything in her future at all — she just kind of blindly gropes forward, hoping the next thing that comes along won’t be quite as much of a dead end as the last thing. She flirts with Piero, then shies away, then flirts with him again. Mom comes home, worrying about where she’s going to get the money to pay Piero — she’s already hocked all her jewelry.

12. At Piero’s office, Piero’s boss tries to explain to the workers how they’re going to get through the crisis of the next stock cycle, how it’s vital to get the money lost from the deadbeats who’ve lost it. Piero needs no coaching on this — he’s regular monster when it comes to making investors feel like losers and idiots for trusting him with their money. And like I say, suddenly we’re seeing everything from Piero’s point of view instead of Vittoria’s. And while Vittoria is vaguely unhappy and fidgety and uncomfortable with everything, Piero is a callous heel who doesn’t seem to have a thought in his head beyond eating and drinking and screwing and doing business — which is to say he’s a stockbroker.

13. After work, Piero, at a loose end, drives over to Vittoria’s place and woos her beneath her balcony (aha! So the Romeo and Juliet reference was intentional!). Why is he attracted to her? Does it have something to do with her mother owing him a great deal of money? More to the point, what does she see in him? Anything? Or is this just how she is with men, just kind of wandering in and out of relationships, not really knowing what she’s doing there, not really having the will to break away? While Piero’s chatting her up, a friendly drunk steals Piero’s pricey sports car and drives it away. This bothers Piero, but not enough to stop him from trying to get a leg over with Vittoria.

14. Next thing we know, the drunk (I think) has crashed Piero’s car and it’s getting fished out of the river. Vittoria is a little horrified by this, but Piero is only concerned about whether or not it will greatly affect the car’s resale value. Everything in the audience’s will screams for Vittoria to go far away from this cad, but she spends the afternoon wandering around the suburbs with him anyway, strolling past a number of rapidly piling up symbols — baby carriages, priests, a recurring horse-drawn cart, and most important, a half-finished new building and the stacks of construction materials surrounding it, which get treated to many disconcerting, lingering closeups.

Vittoria grabs a balloon off a baby carriage, then sends it aloft to her not-very-good friend Marta’s balcony. Marta, the daughter of the big-game hunter, obliges her by getting her father’s elephant gun and blowing the balloon into atoms.

As Vittoria tries to decide to let Piero have his way with her, she rather strangely plunges a chunk of wood into a rain barrel on the new building’s construction site. It’s an odd moment, but it gets odder still, as we will see.

15. Later that night, Vittoria calls up Piero but then doesn’t say anything when he answers.

16. Several times before the end of the movie, we cut back to that chunk of wood in the rain barrel. I don’t know why, but apparently the chunk of wood means something. Is it Vittoria’s soul? Are we checking to see that her soul is remaining afloat? Or is it hope that floats? In any case, the chunk of wood starts to take on significant emotional significance. We want to shout out “go chunk of wood! float! float! float!”

17. Vittoria allows Piero to take her up to his place. Piero is just as big a heel in his own apartment as he is in public. Even though he grew up in this apartment, he has no connection to anything there and seems to have no inner life. He’s decorated the place in cheap bachelor-pad decor and keeps his supply of nudie novelty pens in the study. To underline the metaphor succinctly, he offers Vittoria a chocolate from a box, but when he opens it he finds that the box is, in fact, empty.

Vittoria and Piero fidget around in this apartment, trying to figure out how to start this love affair the two of them apparently want to have, not knowing quite how to do it. The sequence is almost as long as, and serves as a bookend to, the first scene with Riccardo — there, Vittoria was stumblingly trying to figure out how to leave a guy, here she’s trying to stumblingly figure out how to get together with one. “Around you I feel like I’m in a foreign country,” she says, and we know exactly what she means. To make his point succinctly, Antonioni has their first kiss happen through a pane of glass.

The tag line for Annie Hall was “A nervous love story,” but that fits L’Eclisse even better. Both of these beautiful young people are absurdly nervous about something — love or “the world” or something, I don’t think they know. I think Antonioni knows, but I don’t think he wants to tell us — that would somehow ruin everything.

They apparently finally get it on, and Vittoria, for a moment or so, seems happy. Why, we don’t know.

18. Then — crisis! The rain barrel leaks, spilling its water into the street and down the gutter. The camera lingers on this for a long time, the water gushing out of the rusted barrel, Vittoria’s special chunk of wood, her stick of hope, swirling around helplessly as water level drops.

19. Then, as a denouement, some buildings, some faceless people wandering around the cold, modernist, characterless suburb, and a curtain call of symbols. The baby carriage again, the priest, the horse and carriage. A sprinkler is shut off. A modernist streetlamp comes on. There’s that building again, with its heaps of unused construction materials. A man gets off a bus carrying a newspaper — the headline is something like “ARMS RACE SHOWDOWN” and “A NUCLEAR SHADOW,” which almost ruins the whole movie. It’s like Da Vinci writing at the bottom of the Mona Lisa, “She’s smiling because Italy has justemerged from a thousand years of church-dominated ignorance.” Does the H-bomb account for Vittoria’s discomfort, for Piero’s callousness, for the stock-market crash? Is that what the movie is finally “about?” Or is the nuclear threat only a symptom of something else, something harder to put one’s finger on? Because these answers are harder to come to, ultimately I think L’Eclisse is a more daring and accomplished movie than L’Avventura — Antonioni here really seems to be on the verge of something profound. This is tough, unsentimental, rigorous, hugely disciplined filmmaking, with the highest of artistic aspirations — no wonder the purists are so upset by Blow-Up, which is stylish, superficial and glib in comparison.

In the closing moments of the movie, a jet plane flies overhead. The sound-effect geek in me cannot help but note that the “jet plane” sound used is the exact same recording heard a few years later at the beginning of The Beatles’ recording “Back in the USSR.” Coincidence or incredibly-obscure homage? You be the judge.

Casino Royale (2006)

(For those coming in late, I’ve been watching all the James Bond movies in order. You may read my other Bond pieces here.)

As this is a recent movie, I’m going to go ahead and say SPOILER ALERT.

WHO IS JAMES BOND?

James Bond is one cold bastard. He’s recently been promoted to “double-O” status — I may have missed what he was before that. Was he a “regular-O” agent? Did he have a license to hurt? What was he doing for MI6 before they decided he would make good assassin material? Whatever it was, M seems to have a good eye for talent — Bond seems to enjoy killing people almost more than he enjoys boinking the ladies. He’s also young, untried, cocky, reckless, bossy, impatient, quick on his feet and more physical than any five previous Bonds put together.

WHAT DOES THE BAD GUY WANT? One of the many new-to-Bondworld innovations in Casino Royale is the nature of the bad guy. Le Chiffre (“The Number” or, more literally, “The Figure,” both things are of importance to the world of Casino Royale) has the least megalomaniacal and most human scheme of all Bond villains in history. His devious, world-ending plot involves not a giant space-laser or a scheme to blow up Fort Knox or the theft of two nuclear weapons. He doesn’t have a gigantic subterranean lair or a secret labratory or a fluffy white cat. His nefarious plot involves nothing more than short-selling some stock and then winning a high-stakes poker game. Sounds like an average day at Bear Stearns, if you ask me. Of course, his stock-selling scheme involves the dramatic blowing-up of an airplane, but even then he sets his sights low — the plane is empty, and parked on the ground. This is truly a new style of Bond villain — not a monster, not a sadist, not a deformed freak — well, not much anyway — he is, gasp, recognizably human, which is something that extends to the rest of Casino Royale.

Le Chiffre, it seems, is an investment banker for bad guys. He takes the money of an African warlord and uses it in this short-selling scheme. When Bond foils the airplane-blowing-up part of the plan, Le Chiffre has to figure out how to get the African warlord’s money back — hence the high-stakes poker game. He doesn’t dream of world domination, he’s a desperate man in debt to some very bad people. It’s even weirder that he dies at the end of Act III — in a four-act movie — but more on why that all ends upworking later.

WHAT DOES JAMES BOND ACTUALLY DO TO SAVE THE WORLD? Bond kills a double agent at the beginning of the movie — two, actually, if you count the one in the flashback. Wait! What? A flashback? Since when does a James Bond movie have a flashback? Next thing you know, there will be exotic cinematic techniques showing up all over Bond movies, rack zooms and parallel action and shaky-cams and sunburst flares. Is nothing sacred with these heartless bastards?

Anyway, so Bond kills a pair of double agents before the titles roll, one of whom is actually a Brit — another first for the Bond series, if I’m not mistaken (Jonathan Pryce doesn’t count — he was playing an Australian). Next he goes to Madagascar, on the trailer of a bomb-maker. After a stupefying chase at a construction site, a scene of endless leaps, falls, punches, dives and gunplay, he tails the bomb-maker to an embassy, which he promptly destroys. (I swear, Bond exerts himself more in the first 20 minutes of Casino Royale than he does in the totality of Dr. No, From Russia With Love and Goldfinger.)

M, angry with Bond for blowing up the embassy, throws him off the case. Does Bond comply? Yes. He does. He spends the rest of the movie relaxing and hanging out with his buds. No, wait, no he doesn’t — he ignores M’s orders and goes to the Bahamas to try to find whoever the Madagascar bomb-maker was working for.

The Madagascar bomb-maker was working for a d-list villain named Dimitrios. Dimitrios functions essentially the same way a movie producer does, bringing together talent (bomb-makers) and money (Le Chiffre) (all puns intended). Dimitrios has a wife, and Bond seduces the wife to get to the guy. He trails Dimitrios to Miami, where he contacts another bomb-maker just in time to make Le Chiffre’s deadline for blowing up a parked airplane. Bond, as I say, spoils the airplane-blowing-up deal and then enters the high-stakes poker game to make sure Le Chiffre doesn’t make his money back. The plan is that, once broke and desperate, Le Chiffre will turn himself over to MI6 and spill all he knows about his shadowy employers.

Huh. You know, now that I’m looking at it spelled out like that, this plot seems to actually seems to resemble something amazingly like intelligence work. You’ve got terrorists and financiers, you’ve got people who blow up stuff for stock swindles through complicated plausibly-deniable contacts, you’ve got undercover agents and cell-phone traces — by jiminy if that doesn’t sound convincingly real. What the hell are they doing to my movie franchise?! Why, not once does Le Chiffre say to a henchman “Find him and kill him.”

Once Le Chiffre is beaten, he comes to Bond’s side and gladly, gratefully even, turns himself in. Oh wait, no, I’m sorry, what I meant to say is he kidnaps Bond and his girlfriend, tortures them both, then gets shot in the head by his shadowy employers.

And, bizarrely, the movie isn’t over yet. Bond takes himself, the poker money and his MI6-accountant girlfriend to Venice, where he learns, too late, that the girlfriend is (reluctantly) in league with the bad guys. Upon learning this, he takes the only logical course of action — he destroys a Venetian building and kills a bunch of people. Then he tracks the shadowy employer (“Mr. White” — doesn’t sound very shadowy to me, and I for one was very disappointed that, with a name like that, he was not played by Harvey Keitel) to, I’m gonna say Switzerland, and shoots him in the leg.

Whew! What a workout for Bond in this, his longest movie ever. And, I would have to check my notes, but I’m gonna say that this is also the most complicated of Bond plots, although Live and Let Die would probably come a close second. And yet, Casino Royale never feels labored or dense — it flies along through a mid-movie plot shift, an abrupt and improbable love story and a very long poker game (for the record, we see exactly three actual hands of poker in that game, interrupted by two fist-fights, two deaths, four dress shirts, a poisoning, and a heart-re-starting).

WOMEN: There are two women of note in Casino Royale. Three things tie them together thematically — they both make love to Bond, they both are tied to men absurdly below their station (one has a unibrow, the other wears sunglasses with only one dark lens — how bargain-basement Bond Villain could you get?! Dude, you’re Bond Villains, can’t you get a metal skull or prehensile toes or something? Oo-ah, look at me, I’ve only got one dark lens on my glasses! Fear Me!), and they both wind up dead.

Eva Green as Vesper Lynd has the heaviest lifting to do — she shows up halfway through the movie and has to go from “I couldn’t care less about James Bond” to “Omigod, I just totally saw a bunch of guys get freakin’ killed!” to “Help! I’ve been kidnapped!” to “I think I love James Bond after all” to “I am tragically, hopelessly screwed up and don’t want to live any longer” in an hour and fifteen minutes, interrupted by poker hands and killings and emergency medical procedures and car-crashes and torturings and mass destruction. And Craig has to believably answer her.

Guess what? For the most part the love story totally works. I don’t exactly buy a couple of scenes, but not only does Vesper Lynd count as the first Bond Girl with more than two or three attributes to play, but the love story comes off as the first credible one of the series. Lynd doesn’t just fall into Bond’s arms, he has to work at earning her trust, and then her lust. The early scenes of the two of them giddy about their high-stakes adventure are smashing, and I wish they went on for longer. I especially like the scene about the tux, where Bond objects to the one she’s picked out and they argue about fashion. (I’ve only seen high-stakes poker games on ESPN, and I would have loved — loved — to see Bond come swanning into the poker room in his tailored tux to find a table full of guys who look like this.

HOW COOL IS THE BAD GUY? Le Chiffre has a scar on his eye and weeps blood. That’s pretty cool, but the filmmakers seemed to feel that only one minor physical deformity for their bad guy would be short-changing their audiences, so they’ve also given him asthma. Asthma! How the hell are we supposed to be scared of a guy with asthma? Why not a cleft palate or webbed toes? Le Chiffre overcomes his lame disability with style however, and stands as one of the most compelling bad guys of the series, in spite of the fact that he doesn’t even get a cool, spectacular death at the hands of Bond.

NOTES: I dislike the title sequence for this movie,and I don’t care much for the song either, although it’s growing on me. I like the animation, but Bond firing hearts out his gun and punching bad guys into shattering animated diamonds strikes me as dire and lame.

I love the beat where the Madagascar bomb-maker throws his gun a Bond and Bond catches it and throws it back. Was that in the script, worked out during the fight choreography, or improvised on the set?

Due, apparently, to budget cuts at MI6, M no longer has a Moneypenny to flirt with Bond, so she must take on the job herself. I applaud Dame Judy Dench’s playing of these scenes and look forward to some hot Craig-on-Dench scenes in a future installment.

I like his car, and I like very much the spectacular crash that ends its life, but I can’t for the life of my figure out why they would put a defibrillator in the glove compartment.

Giancarlo Giannini, I’m happy to report, survived getting disemboweled, hanged and thrown out a window by Hannibal Lecter, and shows up as some Italian guy who may or may not be a good guy. His and Felix Leiter’s main roles in the movie seem to be explaining to the audience how Poker is played, revealing the meaning behind obscure terms like “stake” and “tell” (Felix: “I’ll stake you — that means I’ll put up the money for you to play.” GG: “There’s his ‘tell!’ That’s how we know he’s bluffing!”) as though anyone walking in from the street to see a movie called Casino Royale would be ignorant of what actually happens inside a casino.

Jeffrey Wright is surely the greatest actor to ever play Felix Leiter and here’s to hoping he comes back for the next movie (although he is not listed as such.) Geez, if the real Felix Leiter was as smart and efficient as Jeffrey Wright, 9/11 would never have happened.

After Bond is tortured by Le Chiffre, is it just my imagination or does he recuperate at a hospital located near Senator Amidala’s house on Naboo? I kept expecting to have Bond look over to see Anakin Skywalker wooing his beloved with his killer lines about how she’s nothing like sand.

Act III of Casino Royale revolves around a poker game. The filmmakers get around this action-movie non-starter by having the game constantly interrupted by fights, killings, showers, poisonings, and no less than four changes of clothes (six if you count Le Chiffre and Vesper). After each one of these events, the characters in the movie go back to doing exactly what they were doing beforehand. Most disappointing of these pulse-raising events is when the African warlord breaks into Le Chiffre’s hotel room and threatens his girlfriend’s arm with a machete. He pulls his punch at the last second, and while I in no way wanted to see the girlfriend’s arm cut off, I was disappointed that the ruthless African warlord turned out to be ruthful after all.

I am also a little disappointed to see Bond relying so much on wireless technology (and I’d love to know if it’s actually possible to get a signal in the middle of the Laguna Veneta). The second time Bond is interrupted in his love-making by a ringing cell-phone I expected him to throw it out the window. The third time I expected him to shoot it.

What makes all this work? The makers of Casino Royale seem to have made a decision early on in the process, one unprecedented in the franchise history. That is, they decided to make a movie about James Bond. Le Chiffre’s death at the hands of some guy who’s name we don’t even know, 3/4 of the way through the movie, works because the movie isn’t about him, it’s about Bond. The love story, absurdly complex by Bond standards, works because the movie isn’t about sex or conquest or gadgets or style or violence, it’s about this guy and his, you know, character. Get this — when this Bond kills a couple of guys in a stairwell or gets thrown off a speeding truck? He still has red marks on his face and hands in the next scene! This Bond, amazingly, takes a moment to steady himself and think about what he’s doing before he heads into a dangerous situation. Did Roger Moore ever take a moment to look at himself in a mirror and wonder if perhaps he’d made a wrong decision? Can one imagine Sean Connery expressing gratitude to a woman for falling in love with him?

The script manages to pull off this feat without making Bond self-obsessed or self-pitying, and, indeed, without actually telling us very much about the character. Other Bonds have been stylish and seductive and funny and charismatic, but this one is something like an actual human being, and, as every real filmmaker knows, there is nothing more intriguing than that.

The Cat in the Hat part 2

Preamble: When my son Sam (6) first began to read, I handed him a copy of The Cat in the Hat and asked him to read the cover. He went for the “Beginner Books” logo in the lower center of the cover and read aloud, “I CAN READ IT ALL BY MYSELF.” Then he looked up, amazed, and said “How did they know that?”

Anyway. To review:

The kids (Sally and I) are All Humanity, and they have been abandoned by God (Mom). They sit and stare out the windows of their house (that is, out the eyes of their skull, or the “windows of their perception” [The Doors of Perception, Aldous Huxley, 1954, The Cat in the Hat, 1957]).

The kids, however, are not alone. No, Geisel has given them a companion — a fish. The fish, we will see, functions as their superego. When the Cat encourages the kids to be bad, the fish instructs them to be good. When I first started reading a spiritual metaphor into The Cat in the Hat it seemed flat-footed and obvious that the spiritual superego would be conveyed by a Christ-like fish, but then Geisel is working on a literal level too, and what else would kids have around the house? A gerbil? Would it make sense for a gerbil to pontificate about right and wrong? What’s more, a fish is the natural prey of a Cat (and a black cat is the traditional companion of the witch) (and “gerbil” was probably not on the list of permissible words).

So: kids, house, absent God, Christ-fish. Let’s move forward.

The Cat arrives. Walks in the door, nice as you please.

Why does this not surprise us? Why has no one, of any age, in all humanity, ever in the past 50 years reached this point of the book and said “What? A six-foot-tall talking cat?! With an umbrella?! Fuck this shit!” We buy it. We buy that the Cat is six feet tall, we buy his clown-like outfit of hat and bow tie and gloves, we buy his umbrella.

We buy the Cat because we, like the kids, are waiting for something. That’s why we picked up the book — to be entertained. God is dead and so our lives are meaningless, we live in a state of anxiety, out of balance, waiting for something, anything, to give us some kind of answers about, well, about anything at all.

“I know it is wet and the sun is not sunny. But we can have lots of good fun that is funny.”

The Cat, master con man, magician and trickster (and lame jam-master — honestly, that’s your opening line, dude, is “fun that is funny” the best you can come up with? Is this how you make an impression?) is all too ready to fill this void, the void God’s absence has made. Obviously, the Cat must be the Devil.

Or is he? Maybe, maybe not — it depends on your definition of the Devil.

“‘I know some new tricks,’ said the Cat in the Hat.”

Tricks, not truth. The Cat has nothing meaningful to offer the kids. Not yet, anyway. And he adds subversion and divisiveness to his offer — “Your mother will not mind at all if I do.”

“Then Sally and I did not know what to say. Our mother was out of the house for the day.” The kids are lost, directionless. They cannot stop the Cat from walking in, they don’t know what to make of him, they don’t think twice about a six-foot-tall cat in a clown outfit with an umbrella (the umbrella shows that the Cat can move in a Godless world and not be affected by it — a skill the kids are keenly interested in). Some kids might react strongly at the sight of a six-foot-tall cat in a clown outfit (the hat, gloves and tie are a parody of being “dressed up,” ie “adult”) who can talk, in rhyme, in anapestic tetrameter, but not these kids — they act like it’s the most normal thing in the world.

Why? Why don’t they run screaming? Why don’t they hide? Why don’t they call the police? Because, as I say above, they are living in a world absent God and are looking for something, anything, to fill that void. They don’t run, they don’t scream — check out their faces — they gaze at the Cat with dumb acceptance. They look exactly like children watching television (which is maybe why Geisel did not put a TV in the house — the Cat is “evil entertainment” enough for one story).

The fish, of course, sets them straight, saying, essentially, “HEY! SIX-FOOT TALKING CAT! HEL-LO?“

(The kids don’t react to the talking fish either — why should they? He’s just a fish, a normal, life-sized, unclothed fish. Once you’ve seen a six-foot talking cat, a normal-sized talking fish [one who’s a wet blanket, at that] isn’t going to raise your pulse much.)

The Cat’s first trick is to humiliate the fish, just as the Devil’s first trick is to force you to cast doubt on your faith. Then he goes into his circus act — the ball, the ball, the book, the fish — as the kids look on in mute helplessness. They’re helpless, entranced by the Cat’s shenanigans. They could probably watch him balance a book (the Book?) and a fish (Christ) while balancing on a ball (the Earth) all day long. I know I could.

But the Cat seems to get bored and restless by his own act, and starts adding to it. He adds a boat, a birthday cake, another book and some milk.

The boat seems to signify Christ again, the fisher of men, while the birthday cake perhaps indicates a “new birth” that has taken place, or will soon. The milk is perhaps that of human kindness, but what could the second book be?

In any case, the Cat is not just juggling household crap, he’s juggling signifiers. And doing so masterfully. As one would expect from the Devil.

The act keeps growing — growing, I’m afraid, into the realm of ridiculousness. A rake, a little man, a Japanese fan, a third book, a cup. I could probably find significance in this yard-sale collection of objects, but I think it’s just household crap now. The string is broken — the Cat, not knowing when he’s ahead, has piled too much stuff into his act.

And so he does the only thing he can — he falls. He falls and all the crap falls with him. If it was losing meaning before, it’s lost all meaning now. Now it’s just household crap all over the floor — a mess. The Cat has failed. He’s failed to entertain, he’s failed to provide meaning, he’s failed to replace God.

The fish scolds him and the Cat, instead of eating the fish like a real cat would, picks himself up, dusts himself off and, undaunted, announces a new game.

And here’s where it gets interesting.

The Cat brings in a box, a big red box (I wonder if the big red box is any relation to the “small red box” of David Bowie’s song “Red Money.” Or the small blue box of David Lynch’s Mulholland Dr.) “In this box are two things I will show to you now,” says the Cat. The “two things” turn out to be, of course, literally Two Things: Thing One and Thing Two.

And this is where I must pause. This is very peculiar. What is going on here? Two things? Two things? The work of Dr. Seuss overflows with imaginatively-named creatures, from Cindy-Lou-Who to Dr. Terwilliger to Gertrude McFuzz, why are these creatures Thing One and Thing Two? They’re not Frick and Frack, they’re not Gary and Jerry, they’re not Wizzer and Wuzzer, they’re Thing One and Thing Two. They’re not even described as creatures, only as things. Dr. Seuss has not only refused to give them names, he’s drained them of all possible personality.

Why?

Well, let’s look first at what they do. What do Thing One and Thing Two do? They introduce themselves to the children (who are helpless to resist), then they trash the house in the name of “play.” They fly kites, they knock over a vase, they push over an end-table, they endanger Mother’s dress and teapot and bed (Dr. Seuss, have you met Dr. Freud?). Come to think of it, Thing One and Thing Two don’t hurt the kids and they don’t damage anything that belongs to the kids — only Mom’s things are endangered.

It is only here that the narrator (“I”) puts his foot down. He realizes, finally, what is at stake here and says “I do NOT like the way that they play! If Mother could see this, oh what would she say!”

When I behave in a moral fashion, I occasionally stop and wonder why. A little voice inside me tells me don’t steal that newspaper, don’t throw that wrapper in the gutter, don’t kick that animal. Who does that little voice belong to?

It doesn’t belong to Jesus, and it doesn’t belong to a talking fish. It belongs, inevitably, I think, to my mother. It is our mother’s voice I believe we inevitably hear when we’re tempted to do something immoral. It’s not Dad’s voice, that seems clear. It is, in fact, probably just the opposite for Dad — if Mom is the one who says “Look both ways before crossing the street,” Dad is the one who says “What, you gonna be a pussy your whole life?”

So maybe the missing Mother isn’t God after all. Or if she is a God, she’s a secular, post-war, atomic-age God. A humanist God. God is absent, the humanists say, and therefore we must be moral, for the good of humanity. There is no punishment or reward that awaits us after life in the godless postwar era, only the world we create here on earth through our actions. What are the kids doing? Waiting for Mom to get home. What are Thing One and Thing Two doing? Destroying Mom’s stuff. This bugs the kids (or the boy, anyway — Sally doesn’t seem to have much of a say about anything in this story — Seuss somehow lived through the entire sexual revolution without ever getting around to writing a feminist book).

Okay. Thing One and Thing Two. Let’s take a step aside for a moment and talk about Bruno Bettleheim. In his book The Uses of Enchantment (which I strongly recommend to anyone who wishes to become a storyteller) Bettleheim instructs us that there are always fewer characters in a story than there appear to be. The Wicked Stepmother in “Hansel and Gretel” isn’t really a wicked stepmother, she’s merely the children’s mother when she’s in a bad mood. There is also no “strange woman who lives in the woods” — that too is Hansel and Gretel’s mother, and the story is how Hansel and Gretel feel threatened by their mother and so kill her (which is why she is magically gone at the end of the story when Hansel and Gretel get back from their adventure). In children’s stories, we kill the mother and replace her with a wicked stepmother so that the child can revel in the negative feelings they have about their mother without actually endangering their relationship with her. The proliferation of characters by proxy is a powerful and elementary device in storytelling and Seuss employs it beautifully here.

Why, I ask, Why are they named Thing One and Thing Two? They are named Thing One and Thing Two because they are not real creatures — they are empty signifiers — they are the physical manifestation of the children’s worst selves.

That is the trick, the truth that the Cat in the Hat brings into the house. The Cat allows the children to see their worst selves. The things that Thing One and Thing Two do are exactly what a couple of bored kids would do if they were feeling devilish enough while mother is out. “Good” kids will sit and wait and watch for Mother’s feet coming up the walk (we don’t see Mother’s face, of course — how does one put a picture of God in a children’s book?), “Bad” kids will run around and engage in horseplay and knock stuff over and break things.

Finally, I know why the kids don’t react to the Cat in the Hat. The kids don’t react to the Cat in the Hat because there is no Cat in the Hat. The kids made him up — they created him. They threw the stuff all over the house, they put the boat in the cake, they put the fish in the teapot, they knocked over the lamp. They made up the Cat to take the blame, like children have done since the beginning of time, but then they took it too far — or just far enough, because when the boy is confronted with the physical manifestation of his worst self, he recognizes it for what it is and demands that it leave.

The superego fish says “Here comes your mother now! Do something, fast!” And the boy catches Thing One and Thing Two in a net amid the rubble of his ruined house and orders the Cat to take them away. Now the house is still a mess and there’s no way the kids can clean it up, but the Cat magically returns with a machine of some kind (the deus ex kind, I’m afraid, now that I think of it) and effortlessly cleans it up.

He does all this while Mother is still walking up the walk. Which is, of course, an impossibility. But that’s okay, because in all probability, none of this ever happened. Not content to push the story into the realm of psychology, Seuss now pushes it even further — there was no Cat, there were no Things, there wasn’t even an event — the boy made it all up, a story, to pass the time while waiting for Mother to get home, exactly like the protagonists of Beckett’s late work (Rockaby, Ohio Impromptu, Company, etc.) “It is midnight. The rain is beating on the windows” begins part 2 of Molloy, “It was not midnight. It was not raining” is how it ends.

So there is no Cat, there are no Things, and there is no destruction of the house. What there is is a boyand a girl alone in the house on a rainy day, and the boy tells the girl a story, a story about a giant cat who shows up and wrecks the place, who shows the children their worst selves, so that they may then, with the help of their superego fish, know how to act when their Mother is gone.

Now that the kids have cleared this psychological/spiritual hurdle, Mother does indeed return. The children don’t ask her where she’s been or why she was gone, they only light up like Christmas (sorry) trees upon seeing her.

“Did you have any fun?” asks Mother. “Tell me. What did you do?” To which the boy asks “Should we tell her about it? What SHOULD we do?” Well, indeed, what should he do? The children have taken their first step into a moral life; they’ve fantasized about destroying the house, they lived that fantasy to the fullest, but they have then thought better of it. They now have a secret — some part of them wanted to destroy their Mother’s house. If they tell their Mother, they run the risk of losing her trust (unless they’re Catholic,of course — confession is always forgiven). If they don’t tell her, if they keep their secret, they take a step toward adulthood, a step toward a moral life independent of their mother. Which is, of course, the whole point of good parenting, to get to the point where your children are capable of making their own decisions. Which is, of course, the story of God and humanity — God leaves us alone, refuses to show himself, so that we can learn to make decisions on our own, exercise our free will. In that regard, Mother (God) and Cat (Devil) are part of the same bargain — Mother sends the Cat in as a test of our will, our faith, our sense of duty.

Finally, The Cat in the Hat is not about the Cat, or the hat, or the fish, or the Things, or the mess. It’s about the boy creating a narrative, to entertain himself and his sister (maybe that’s why he has a sister at all, to be an audience). The boy is Seuss, most likely, and he creates a narrative because that’s what storytellers, and all of us, really, do in order to make sense of the world. We make up stories about God and the Devil, or the Cat and the Fish, or Hamlet and Claudius, or Harry and Voldemort, or James Bond and SMERSH, so that we might have a roadmap to guide our life.

The Cat, as cats will, comes back. But that’s a story for another day.

The Cat in the Hat part 1

It’s difficult for us, now, to fully appreciate the impact The Cat in the Hat had on generation of parents, children and educators. The Cat, as an aide to teaching children to read, seems as obvious and omnipresent as the alphabet itself and has not been improved upon in 50 years.

The story of the book, which has been told many times (and can be found in greater detail here), is that the reading programs of the US were a laughingstock for their inefficiency and waste, and an editor of children’s books decided to take it upon himself to rectify the situation. (If someone could find the name of that editor, I would be in your debt.)

Ted Geisel (that is, Seuss) was given an assignment to create a children’s reading primer that would tell a story that uses only 220 easily-recognized words, which were drawn from a list provided by an educational theorist. One might imagine that a book produced by this technique, in kind and understanding hands, would turn out something like PD Eastman’s charming but plotless Go, Dog. Go! But Ted Geisel came up with something more original, daring and explosive.

(Eastman would later climb this mountain beautifully with the woefully underrated Sam and the Firefly, which I hope to get to at another time.)

The story goes that Geisel wrestled with the difficulty of creating his primer for months before taking the first two words from the list, “cat” and “hat,” and saying, essentially, “screw it, I’ll call it The Cat in the Hat,” and going from there.

The Cat in the Hat does its job as a primer very well indeed. It’s lively, funny, and tells a complete story with its bare-bones vocabulary (Seuss would later, of course, trump himself with the 50-word Green Eggs and Ham, which I discuss here). But the thing that makes The Cat in the Hat a classic, what makes it a book that sticks with you, is not that it teaches children to read but that it contains mysterious worlds of allegory and symbolism. It’s open to many different readings and addresses, in its way, some of the most profound questions of human life.

There was a wonderful piece by Louis Menand in the New Yorker a few years ago that gave a modernist interpretation to the story, and which is not available online, (although some criticism of it is — curse you, internet!). The Cat, says Menand, is Seuss himself, who’s been thrust before an audience of children and is required to entertain them with nothing but a handful of arbitrary, meaningless words — cat, hat, wall, cake, run, thing, etc.)

(The Cat carries an umbrella but the word “umbrella” does not appear in the book — not on the list, and difficult to fit into Geisel’s patented meter in any case.)

Having nothing to work with, the Cat throws a bunch of crap together (a ball, a rake, some books) and puts on a piss-poor circus act. One can feel Geisel’s frustration — “I could tell you some wonderful stories, but look what they gave me to work with!” — as the Cat abandons his mission of entertainment and moves on to destroying the house. The Cat becomes a Beckettian protagonist — ‘there is nothing to express, nothing with which to express, nothing from which to express, no power to express, no desire to express, together with the obligation to express” is the way the author of Waiting for Godot put it.

(Beckett, Seuss’s exact contemporary, would dedicate his life to paring down his work to Seussian levels of economy — was this the influence of The Cat in the Hat? Was it the dare of Green Eggs and Ham that took Beckett from the flourishes of his youth to the spareness of his mature work? The opening sentence of More Pricks Than Kicks, an early collection of stories, is “It was morning and Belacqua was stuck in the first canti in the moon.” The first line of his last work, Worstward Ho, is “On. Say on. Be said on. Somehow on. Till nohow on. Said nohow on.” Worstward Ho, like many of Beckett’s late prose pieces, is about the author’s inability to express himself with the tools at his disposal — he would have recognized the cat’s dilemma immediately.)

The Cat, of course, has been denatured, neutered if you will, through time and love and wide acceptance, as all successful comic anarchists are, from WC Fields to the Marx Brothers to Richard Pryor, but the book itself still retains its mysteries and wildness. We see the Cat on a bookbag or bong and smile — he is there to comfort and charm. But, like Charlie Brown (another classic baby-boomer figure), the Cat represents something much darker and more interesting than the merchandising suggests.

“The sun did not shine.” That’s the opening line of this beloved classic. “The sun did not shine.” Not to torture Seuss’s place in the Modernist pantheon too greatly, but I’m reminded that the sun does not shine in a great many of Ingmar Bergman’s movies. In his case, it’s partly because the stories Bergman tells take place during the Swedish winter, when the sun does not shine as a matter of course. But Bergman always used the lack of sunlight (one of the peaks of his art is actually titled Winter Light) to denote a lack of divine light, an absence of God in the lives of his characters. (The Seventh Seal, lest we forget, was released the same year as The Cat in the Hat. There truly was something in the air — maybe fallout from H-bomb tests; that’s what critics thought the characters in Beckett’s Endgame, also published in 1957, were hiding from in their skull-like bunker.)

(When the sun does shine in Beckett’s work, as it does, unremittingly, in Happy Days, it is a harsh, burning, scorching blast without night. Light in Beckett is always important, whether it’s Krapp caught in his Manichean dualism or the protagonist of “Ohio Impromptu” stuck in his unending night or the beings of “Lessness” caught in their gray un-light.)

“The sun did not shine. It was too wet to play. So we sat in the house all that cold, cold wet day.” Well, this is Endgame. Endgame is about exactly this — two people locked in the house on a cold, wet day. All the Cat would need to do is bring in two old people in garbage cans instead of two Things in boxes and they would be the exact same work. The characters in Endgame, like the characters in Waiting for Godot, like the children in The Cat in the Hat, are faced with interminable boredom and nothing but a handful of ordinary props (a stick, a hat, a chair) to entertain themselves. Geisel stands squarely at the crossroads of mid-20th-century angst. Except, of course, he’s an American, which means that his characters’ problem is that they have things, but those things are useless consumer junk, the things we buy with our post-war dollars in order to feel less empty. The kids in The Cat in the Hat sit staring out the window in their house full of junk — a ball, a bicycle (Beckett again, with Molloy’s preferred mode of transport), a badminton racket. In literal terms, the stuff is useless to the kids because it’s all “outdoor” stuff, and it’s raining outdoors. But I am reminded, again, of Beckett, and his sense of indoors and outdoors. For him, the outdoors is everything outside his skull, that is the “real world,” and the indoors is his mind. The Cat kids are stuck not in a house but in their own minds, or in the mind of Geisel anyway.

(That’s why the shelter in Endgame has two windows — the characters are all inside Beckett’s head, and the windows are his eyes out onto the world, which, in Beckett’s view, is a blasted wasteland devoid of life.)

(It’s also worth noting that Beckett’s characters, like the boy and girl in The Cat in the Hat, are pseudocouples. That is, Didi and Gogo, Hamm and Clov, Mercier and Camier, etc, are not really two different characters, but only different aspects of the same mind, a pair of characters who appear to be a couple but who are really only one character arguing with him-or-her self.)

So I’m tempted to bring a both a psychological and spiritual reading to The Cat in the Hat, and will try to do so hand-in-hand here.

The kids stare out the windows of their suburban house the exact same way the characters in Endgame stare out the windows of their shelter, the same way Winnie stares at the landscape in Happy Days (Winnie also has nothing with which to face eternity but a toothbrush, an umbrella (!), some makeup, a hairbrush and a revolver — Seuss, apparently, couldn’t bring himself to include suicide in his list of possible activities for the kids of The Cat in the Hat), the same way The Unnamable stares, unblinking, out of its jar, at the void. They’re looking for life, and meaning, where experience has taught them none exists.

Beckett’s characters search for any signs of life at all — the possible appearance of a flea counts as a major plot point in Endgame — but the kids of The Cat in the Hat are searching for one specific sign of life — their mother.

Because their mother is out on this cold, cold wet day.

It took Time Magazine until 1966 to ask “Is God Dead?” (that’s Time for you, always behind the curve) but the question was very much on the minds of all the big thinkers in the middle decades of the 20th century. For obvious reasons. The end of the world had just narrowly been avoided, only to be threatened by a different end of the world, one that was in the hands of “the good” but which was still infinitely more scary than, say, Nazism.

In any case, the death of God was the central question informing Bergman’s greatest dramas, The Seventh Seal being only the most famous (Beckett’s works support a spiritual reading, but I think in the end his works are all about the act of writing itself — it is only coincidental that they invoke humanity’s relationship to God). But it’s not too far a leap, I think, to suppose that the absent Mother in The Cat in the Hat is God. God has left the children at home and gone off somewhere, she said she’d be back (like Godot) but there is no sign of her. And so all the children can do is wait (like Godot). They have a house full of stuff, certainly there’s a box of toys somewhere (although Seuss declines to put a TV in their house), but all the kids want to do is sit and stare and wait. Clearly, their mother’s absence worries them. Where has she gone, what is she doing, why is she not there? The story doesn’t say, but then God didn’t leave a note either.

The kids will sit and stare and wait (“All we could do was to Sit! Sit! Sit! Sit!” says the narrator [“I,” which I supposed would make “Sally” “Not I”]). Their house full of junk is meaningless and the world outside the house of their perceptions is a blasted void. Nothing has meaning, everything is dark, until their mother returns. Their anxiety about their lives in this suburban purgatory is palpable.

Alas, this is going on longer than I intended and my time grows short and I’m only on page 3. I will pick this up again on the nonce.

Movie Night With Urbaniak: L’Avventura

The first thing you need to know about L’Avventura is that it has no plot. The second thing you need to know about L’Avventura is that, in spite of having no plot, it is still tremendously exciting.

I don’t know how it manages to do that.

This was a rare instance of

actually requesting a movie to watch, rather than the two of us just kind of pawing through my DVD collection until we find something we both want to watch. He showed up with the movie clutched in his slender, spidery, indie-stalwart hands, still it its shrinkwrap, still with the price tag from Amoeba on it.

The movie is loaded with symbolism, but the characters aren’t symbolic — they’re real people. At least I think they are. Every time I tried to read the movie as purely symbolist it would answer with a scene that said that it was actually a character study.

Come to think of it, the story structure kind of reminds me of Raymond Carver. It’s not about big moments, or about a coherent dramatic arc. It’s about these people caught in a situation and it kind of sits there and studies how the people behave. And all the incidents that make up the narrative are all really small and not necessarily significant in and of themselves, but are so specific, and so ineffably cliche-free, they retain our interest. We keep watching partly because we want to know why the people are doing the things they’re doing and partly because we want to know why the filmmakers chose to shoot the scene. What do all these little moments of behavior add up to? Will the trashy celebrity who shows up in Act III show up again in Act IV? Why this town, why this church, why this shirt, why this room, why this hour of the day? Resonances and echoes show up all over the place (just like they show up in that scene with the church bells) and every time you think a scene isn’t going anywhere the scene goes somewhere, but never where you thought it was going.

In other ways, the story structure reminds me of Kubrick, in that there are long slabs of narrative dedicated to illustrating one plot point and we don’t know what the plot point is until we arrive at it at the end of the slab. Those slabs are, roughly:

1. Let’s go on a cruise! (30 min)

2. Looking for Anna (30 min)

3. Will Sandro get a leg over? Will Claudia give in? (30 min)

4. Claudia commits (30 min)

5. Crisis (17 min)

1. So there’s this woman, Anna. She’s young and Italian in 1960. She was probably a child during the war. Her father is a builder of some sort. We first see her have a halting conversation with dad in front of one of his building projects. He’s tearing down some old buildings to put a new one there.

says that’s a major theme of the movie: destroying down the old to make way for, what, exactly? The anxiety of that question hangs over the entire narrative.

Anna’s in love with Sandro. Or maybe she isn’t. Claudia is in love with Anna. Or maybe she’s in love with Sandro. In any case, there’s a lot of unspoken tension between the three of them. Maybe Anna isn’t really happy with Sandro and would rather go with Claudia. Maybe the opposite is the case.

This bunch of funsters go on a cruise in the Mediterranean with some friends. Their friends’ relationships are, to put it mildly, dysfunctional at best and doomed at worst.

Theyarrive at an island. Folks go swimming, folks climb on rocks, folks bicker.

2. Somebody notices Anna isn’t around any more. The group searches the island. They call the police. The police and whatever authorities do things like this search the island. For 30 minutes we watch people climb over rocks and gaze into the water and wonder what the hell happened to Anna. Because either she’s hiding, which is unlikely, or she’s unconscious somewhere we haven’t looked yet, or she’s dead somewhere we haven’t looked yet, or she got on a boat we didn’t see and rode off somewhere. If she’s dead, she could be dead by suicide or by murder or by accident.

3. Apparently Anna is not on the island and nowhere near the island. The other couples go on with their vacation while Claudia worries about Anna and Sandro half-heartedly searches a nearby town. I say half-heartedly because, well, for some reason Sandro, now that Anna is gone, doesn’t want to waste the opportunity to make a move on Claudia. Claudia is horrified by Sandro’s advances — her friend-girlfriend -Sandro’s-girlfriend is missing and she feels guilty and terrible about it — this is no time to be messing around the ancient, tumble-down towns of rural Italy.

The narrative starts to splinter here as Sandro gets distracted and Claudia gets anxious. Sandro runs into that trashy celebrity mentioned above, Claudia gets caught at a society gathering refereeing for her non-friend Giulia’s (or is it Patrizia’s?) makeout-session with a Bob Denver-lookalike teenage artist, whose paintings are an affront not just to the beauty of the villa where he’s staying but an affront to their subjects and to the act of painting itself.

4. Claudia suddenly, and without preamble, gives in to Sandro’s advances and declares herself desperately in love with him. Maybe she’s been in love with him from the beginning, maybe she’s just recently decided she is, maybe she’s fooling herself. We know Sandro is a lout who has no idea what love is, that seems clear enough, but Claudia seems to be cut from different cloth. First, she’s the only one on Team Ennui who wasn’t born wealthy, second she’s the only one who carried any sense of guilt about Anna’s disappearance all the way through Act III. This is where I started to think L’Avventura is about postwar Italy, how a new generation chose to move ahead into some ill-defined bright tomorrow while others couldn’t help but feel a sense of guilt and loss for what had been destroyed in the war. In any case, loss, the careless destruction of the old and beautiful, the replacement of the old and beautiful with the new and ugly (and profitable) is one of the movie’s ongoing concerns.

griped toward the beginning of the movie that he didn’t like the actor playing Sandro, that he was uninteresting and shallow, giving a kind of generic “60s leading man” performance. By the end of the movie he had changed his tune, realizing that the actor was not giving a shallow performance, he was performing the action of being shallow, which is a completely different thing. That is, it’s not the actor who is giving a generic “60s leading man” performance, it is Sandro who is giving it. As Act IV goes on and Sandro starts to reveal his true ugliness, shallowness and restlessness he becomes infinitely more interesting. Conversely, Claudia, once she gives up on honoring Anna and gives in to Sandro’s indelicate advances, becomes slightly less interesting as she pines and swoons and tries on different outfits.

Why does Claudia fall for Sandro? We don’t want her to. If she always had a thingfor him, she’s an idiot, and she doesn’t seem to be an idiot. I prefer to think that both Sandro and Claudia had a thing for Anna and when Anna vanished she created a kind of relationship black hole that sucked Claudia and Sandro toward each other. Claudia becomes attracted to Sandro because they now have something in common — missing Anna.

Let’s say for the moment that Anna is a symbol for something really pretentious like “the soul of Italy.” The soul of Italy has vanished and only Claudia seems to really care about any of that. Sandro doesn’t care — he made his peace a long time ago that he wasn’t going to create anything beautiful. He had his chance — he coulda been a contender architect, we learn at one point, but gave it up for the short-end money. Then we see him knock a bottle of ink over onto a drawing someone’s making of a gorgeous church window. Sandro cares about the soul of Italy insofar as he wishes to destroy it as quickly as possible. To replace it with what? Well, that’s where Sandro’s anxiety comes in. He doesn’t have any idea what he’s going to replace it with. Maybe that’s why he makes such a fast move for Claudia — he’s just reaching out for the nearest available object to replace the hole in his soul that opened up when Anna disappeared.

5. Sandro and Claudia, having declared their undying love for each other, check into a hotel where their friends are staying. There’s a big party going on. Claudia is tired and wants to stay in the room, but Sandro gets duded up in his tuxedo to check out the action. Claudia can’t sleep and mopes around the room while Sandro wanders, bored and restless, among the empty suits and fashionable gowns. He sits down to watch a TV show in the hotel TV room. We don’t see what’s on TV, but it seems to be a show primarily about things that go “WHOOOSH!” He watches this scintillating program for a few seconds before wincing at it and moving on.

Claudia suddenly has a vision that Anna has returned, which she feels would be really bad at this point because it means that her love with Sandro would be doomed. She rushes downstairs to the empty ruined ballroom and finds Sandro making out with the trashy celebrity from Act III.

Claudia dashes out of the hotel, as one does in situations like this, and Sandro chases after her. (The trashy celebrity begs Sandro for a “souvenier” and he disgustedly throws a wad of money at her. She lazily gathers it up with her bare feet like an octopus capturing its prey.)

Sandro collapses on a bench and cries. Does he feel something? Is he worried about losing Claudia? Is he mourning Anna? Is he mourning his own soullessness?

Claudia approaches. A satisfying ending would be: she hits him with a big rock and screams “I KILLED ANNA AND ATE THE BODY, YOU FOOL!” But that’s not what happens. She should, at the very least, be very angry at him — he went pouncing off after Paris Hilton mere moments after declaring his unending love for Claudia — and did so while Claudi was right upstairs! But we watch as she balances that anger for a moment, as she literally balances her own self, gripping the back of the bench to keep herself upright. Then she places a hand on Sandro’s shoulder, as though to forgive him, then, incredibly, she moves her hand up to his head, to pull him to her, to comfort him. We have no idea what happened to Anna, all we know is she’s gone and, as far as the movie is concerned, isn’t coming back.

(Idea for sequel: L’Avventura II: Anna’s Return!)

And then the last shot, reproduced above. Half mountain, half ruined building, the wounded, conflicted, embattled couple facing their uncertain future. “The ‘adventure,'” says

, is the couple’s adventure into adulthood.” “And Italy’s adventure into the future,” I add, half-heartedly, because I’m really not sure.