Guardians of the Galaxy part 3

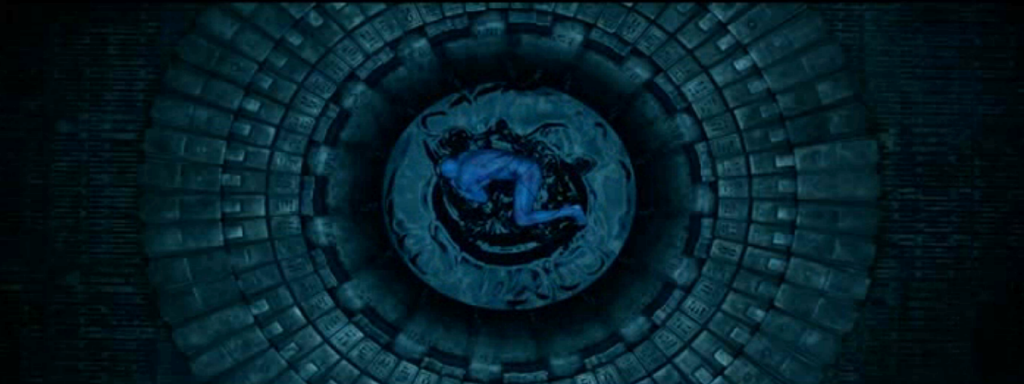

Thirteen minutes into the narrative, the chief antagonist is introduced, Ronan the Accuser. He lives in a tank of goo on a Kree spaceship called the Dark Aster (possibly a reference to the classic early John Carpenter movie Dark Star?)

What does Ronan want? His actable goal, his cinematic goal, is “to get the whatsit that Peter stole.” It was his goons who tried to get it from Peter already. But what will that get him? What does the antagonist want?

Guardians of the Galaxy part 2

After its heart-rending “cold open” in the hospital, the narrative of Guardians leaps ahead a few decades. Peter is now in his 30s, and is engaged in some high-tech sci-fi shenanigans. As the titles roll, a one-man heist sequence plays out, an affectionate parody of the opening of Raiders of the Lost Ark. Peter is no longer a sobbing boy or a helpless victim, he’s now a swaggering space-pirate looting ancient cities for lost treasure. His Walkman is no longer his shield, exactly; it’s now more like the vessel of his mojo. Instead of Indiana Jones carefully reading clues, dodging traps and insisting “That belongs in a museum!” we have Peter casually jiving his way through a ruined planet’s rainy landscape, kicking deadly lizards out of his way and even using one as a pretend microphone.

Guardians of the Galaxy part 1

For a big-budget, gee-whiz, goofy-space-opera summer blockbuster, Guardians of the Galaxy begins surprisingly quietly.

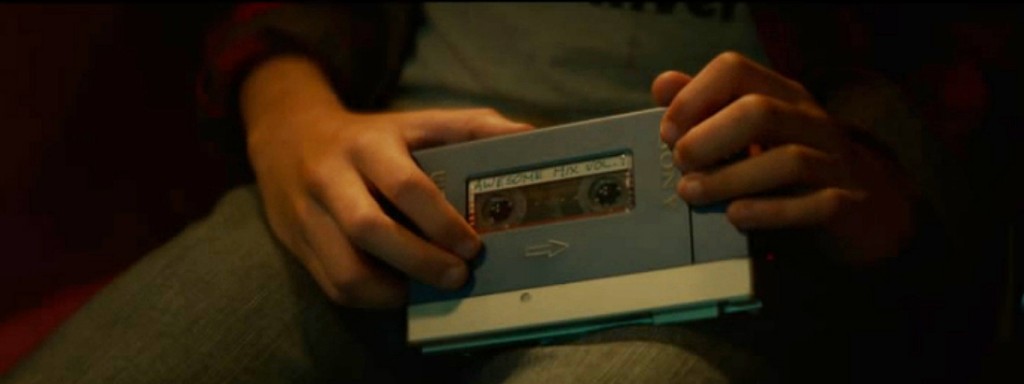

A boy sits in a hospital corridor in 1988 cradling his Walkman. “Awesome Mix Vol 1” reads the label. He’s listening to “I’m Not in Love” by 10cc. “I’m Not in Love,” from the summer of 1975, was instrumental in launching the career of 10cc. Originally written to a bossanova beat, it was reworked to feature an all-choral backing, made up of hundreds of overdubbed voices. Whether this was on the minds of the makers of Guardians or not, but the strength-in-numbers / linking together vast chains of individuals theme resonates throughout the movie. The subject matter, oddly, is a young man refusing to say he’s in love, until finally he’s deluding himself.

What does that have to do with the boy in the corridor? Well, his mother in dying in the next room, and he’s intent on holding in his feelings. His Walkman here is his shield, his way of holding the world and its horrors at arm’s length. And we will find that, in a way, the whole narrative of Guardians, with its reluctant hero who eventually joins society and does so, successfully, on his own terms, is about a boy who insists that he’s not in love until he finally admits that he is.

(“I’m Not in Love” is also a song from an album titled Original Soundtrack, which is a fine enough joke in its own right.)

On top of all that, “I’m Not in Love” sets the tone for Guardians‘s meta-narrative of “modern” humanity and its relationship with culture, especially culture of the past. A pop song from 1975 is an odd thing, I think, to find on the Walkman of a boy in 1988, until you realize, much later, that the “Awesome Mix Vol 1” was a gift from his mother, the same mother who’s dying in the next room. It’s not “his” music the boy is listening to, it’s his mother’s. The “Awesome Mix” is a kind of parting gift from mother to child, an invitation to popular culture and a sweet sampling of “adult” emotions, to guide a son through the rockier moments of life. The culture the boy’s mother has chosen to share is unabashedly popular, populist, “fun” (as opposed to “serious”) and life-affirming, all of which adjectives describe Guardians as well. Just as the boy’s mother’s mix-tape is designed to guide and celebrate, so is the movie.

some thoughts on Guardians of the Galaxy

When the previews for Guardians of the Galaxy started showing up in theaters, I was struck by the ways they used Blue Swede’s “Hooked on a Feeling.” That song was a nutty novelty hit when I was a wee lad in 1974, and I wondered if anyone else in the theater even remembered the recording, much less felt the sense of nostalgia I did when I heard it. Would people think that “Hooked on a Feeling” was some kind of message from another planet? What could its inclusion in the trailers for a Marvel movie possibly mean, except that, obviously, Guardians of the Galaxy was not a movie to be taken entirely seriously? And yet, that song, and the aesthetic choice that led to its inclusion in the movie, is a key part of understanding the appeal of not just Guardians but of the entire Marvel Cinematic Universe project.

X-Men: First Class part 11

The most striking, most unusual feature of the screeplay for X-Men: First Class is that it does not have a traditional end-of-second-act low point. In the typical superhero narrative, the story is: villain appears, superhero fights, villain triumphs, superhero comes back from defeat. That doesn’t happen here, because First Class, lest we forget, is a romance. The romantic comedy goes: boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl back, but a straight romance doesn’t need a happy ending, and in fact can have a tragic ending, as in Romeo and Juliet or The Fly. In the romantic tragedy, the two leads want to be together but cannot — the forces arrayed against their union are too great. The forces arrayed against Erik and Xavier are all internal, and deal with their past and upbringing, irreconcilable questions of identity and personality. Erik cannot wake up in the morning and no longer be a persecuted Jew, and Xavier, for all his psychic power, cannot imagine life in Erik’s shoes, because he’s always had everything he needs. If they could change, if they could reconcile their differences (that’s why the movie spent the first act underlining those differences), they could stay together and save the world, but the narrative drives them irrevocably toward breakup and tragedy.

So what is the structure of First Class? I would say it’s: Act I, Erik and Xavier head on a path toward each other with Shaw as their common enemy, culminating in their meeting; Act II, Erik and Xavier pursue Shaw together and fall in love through the action of doing so, culminating in the raid on the Russian general’s house; Act III, a retreat to more internal matters as Xavier attempts to temper Erik’s anger with love while he trains his recruits; and Act IV, where Erik’s and Xavier’s relationship is put to the test: can they work together, save the world and be happy, or will the polar opposites of their pasts hinder their efforts and tear them apart, simultaneously bringing the end of the world? (“The end of the world” is an overused trope in superhero narratives — hell, a lot of narratives — but when it’s tied to a love story it become elevated; a romantic breakup often does feel like the end of the world, First Class merely literalizes it.)

X-Men: First Class part 10

As the fantastic merges with the historic, no less a personage than John F. Kennedy is brought in lend weight to plot of X:Men: First Class. The footage is real, as is the footage that follows, of stores being sold out of canned goods and people stockpiling fallout shelters. Fallout shelters were big news at the time. The Twilight Zone had featured an episode about a fallout shelter a year earlier than the Cuban Missile Crisis; Bob Dylan, in February 1962, recorded a song about them, “Let Me Die in My Footsteps.” What seems quaint now, the idea that one could run and hide from a nuclear war, was, unbelievably, very real and present to the general populace. I myself was a mere tadpole in October of 1962, but my parents assured me, yes, for a few days, you pretty much just didn’t know if the world was suddenly going to end. In its way, it’s a comforting thought, that this level of madness was brought on by fantastical mutants bent on world domination, as the reality of the situation is too mind-bending to absorb.

In practical terms for the adventure narrative of First Class, the Cuban Missile Crisis is a clue for our protagonists to find Shaw. Remember, “to save the world” is not their goal, only “to find Shaw.” Xavier to stop him (to make the world a better place), Erik for his private, personal revenge. Xavier is high-minded, Erik is low-minded. Xavier may be who we want to be, but Erik is who we are.

X-Men: First Class part 9

While Erik and Xavier, er, “have their way” with Emma in Russia, Shaw and his team make their move on MiB HQ. Shaw is striking back at Xavier for poking around with Cerebro (the shots of Xavier with his head in Cerebro, ecstatic and lit from within, tie him to 60s mind-expansion gurus like Timothy Leary and John C. Lilly). First they kill all the humans, then they come for the mutants. You can come with me and be free, Shaw says, or stay here and live in slavery, and the camera points to Darwin, because, you know, slavery. In the scheme of First Class, this is like the Students for a Democratic Society (which formed in — you guessed — 1962) crashing the peace-and-love party. Shaw, of course, is no student, he’s been around forever, he’s more like an outside agitator, a warmonger disguised as one of the hip kids, fomenting rebellion because, well, that’s the business he’s in. “You can join me and live like kings and queens,” he says, looking at Angel, but we’ve seen how Shaw treats Emma — there will be no equality in Shaw’s version of the future. Angel, she of low self-esteem (she is a stripper, after all) comes with Shaw, but Darwin and Havok try to stop her. Darwin, sadly, goes from being the non-stereotypical black guy to being the stereotypical black-guy-in-the-movies, and becomes the Noble Sacrifice to the cause, the first one to die in the fight against evil.

Read more

X-Men: First Class part 8

The joyous gathering of the new X-men recruits, in the inner sanctum of the MiB HQ, echoes what was happening in college campuses all over the world. It begins with young people discovering themselves, claiming their powers, forging new identities and enjoying their commonality and diversity, and ends with one of them destroying the Establishment leader in effigy. I was struck by the moment of Havok slicing and burning the statue of the MiB (odd that he has a statue of himself on his compound) and trying to remember what it reminded me of. Then I realized, of course, it reminds me of campus protests, where all sorts of unspeakable acts are visited upon the statues of the Great White Men who built the temples of learning but whose relavence had long since vanished. The young recruits are the campus youth movement, the Other gathered in an establishment sanctuary, free from the worries of employment (stripper, cabbie), freed from imprisonment, free to concentrate on “finding themselves,” and, thus, free to concentrate on the next thing. The next thing, in college campuses, is supposed to be “studying,” and here in X-Universe is supposed to be “finding Shaw,” but the end result in both cases is the same: “saving the world.” That’s what the 1960s youth movement, the Hippie Dream, was all about, although, like with the X-Men recruits, “toppling the Establishment” (or at least thumbing one’s nose at it) is the first step in defining themselves. The reason Bob Dylan became the “voice of his generation” was not his politics, it was his refusal to be identified, to be pinned: “Whatever you say I am, that is what I am not.” That strikes at the core of the appeal of X-Men from the beginning, and First Class is not just a history lesson, but an X-Men history lesson. Other movies pay homage (or lip service) to their comics origins, First Class actually puts its comics in historical context and thus illuminates their genuine cultural import.

X-Men: First Class part 7

Erik and Xavier, two straight men in 1962, have fallen in love. Like all straight men who fall in love, they must find things to do together in order to have an excuse to hang out. The manlier the better. Hence, the first thing they do after deciding to work together to find Shaw is to go to a strip club and indulge in some very groovy Mad Men style sexist shenanigans. The joke here being, of course, that they’re not looking for sex but for mutants, in this case a winged young lady named Angel Salvador. Still, the message is clear: like James Bond, Erik and Xavier have found that saving the world doesn’t have to mean you can swing a little. Next, they find a young black cabbie in NYC named Armando Munoz, a imprisoned young man named Alex Summers, an awkward youth with a hyper-sonic voice named Sean Cassidy (not Shaun Cassidy), and, briefly, a taciturn guy named Logan, who, in the movie’s single funniest moment, politely rebuffs their advances. Even Erik and Xavier strike out sometimes, and not everyone wants to join a family.

The team that they assemble are all variations on the Other — a stripper, a black youth, a prisoner, an awkward, rejected teen boy, they’re like the cast of a Bob Dylan song come to life. We’re watching the 1960s come together. Logan, of course, had his ’60s a hundred years earlier, this is not his movement. (I also note that Armando, while black, is not black and angry, just a working-class dude driving a cab, which makes him “other” enough in 1962 New York, no reason to disenfranchise him as well, or make him a stereotype.)

X-Men: First Class part 6

While Shaw is at the North Pole in his submarine, preparing to destroy the world or something, Raven and Hank waste no time in getting to know each other. They bond over their shared desires to appear “normal.” The 1960s are still young, and the postwar conservativism that affected the US, despite the election of Kennedy in 1960, is still very much the order of the day. Perhaps the hippies of San Francisco would accept a boy with hands for feet or a scaly blue young woman, or perhaps they would be accepted at Harvard, where Timothy Leary was beginning his experiments with LSD. (Both Raven and Emma wear miniskirts even though they would not be invented until 1964. Mutants, as always, lead the way in evolution.)

Hank, we learn, has developed a serum that, he believes, will help a mutant maintain his or her abilities while making them appear “normal.” (How this is supposed to work, I have no idea — that’s right, I doubt the veracity of the science of X-Men.) Raven can’t wait to be jabbed by Hank’s needle, so to speak, but Erik comes along to pour cold water on their romantic-scientific tryst. Not only is Erik older and sexier than Hank, he’s prouder and more persuasive than Xavier. When he tells Raven “I wouldn’t change a thing,” it carries more weight than when Xavier says “Mutant and proud,” because Erik has been through the worst a mutant, an Other, can be put through, and come out the other side, while Xavier has never had to suffer a day in his life. Thus, he turns Raven’s head as her one-on-one with Hank suddenly becomes a triangle.