The (other) Man Who Knew Too Much

While it’s too much to say that the 1934 version of The Man Who Knew Too Much is “better” than the better-known 1956 version, there are areas where the original is a substantially better work.

The biggest tonal shift is the married couple. In 1956 they are middle-class Americans, Christian, uptight and oblivious to their surroundings, blundering around foreign countries at a loss. In 1934 they are wealthy, white-tie sophisticates, world-travelers who drink, trade bon mots with celebrities and joke about sleeping around. The shift makes the 1934 version both more giddy and more exotic — this couple seems to take the kidnapping of their child in stride, a simple problem to be solved with reserve, pluck and stiff upper lips, and there is plenty of time for banter and hijinx, and instead of recognizing the couple as people we know, we wonder what their private life must be like when they’re not dashing about Europe and participating in skeet-shooting competitions.

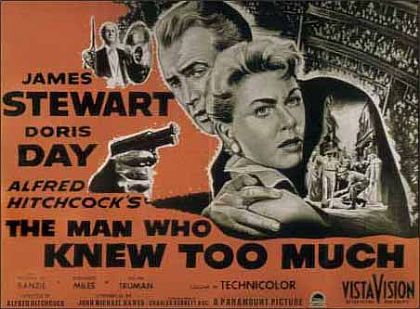

The Man Who Knew Too Much

The Man Who Knew Too Much could be one of the most influential movies in history, although it may not seem like it at first.

In the first 20 minutes alone, we see an American couple whose marriage is on the rocks trying to patch things up with a bus ride through Morrocco (which showed up later in Babel) an American doctor and his wife attending a medical conference in a foreign country getting tangled up in international intrigue (which showed up later in the echt-Hitchcockian Frantic) and a hectic chase through a crowded Morroccan marketplace (which showed up later in Raiders of the Lost Ark). For good measure, Jimmy Stewart also mentions that he was stationed in Casablanca during WWII. With movies like these flooding the culture it’s amazing that Americans ever leave home at all.

(And of course the whole “assassination at the concert” sequence was lifted for the 70s Hitchcock pastiche Foul Play.)

Friend

I stumbled across this piece today. It dates back to the early 90s. Even though I performed it fairly regularly, I have no memory of having written it. That’s how it goes sometimes.

She could never take care of herself. She was an accident waiting to happen, she was a bull in a china shop, she was dead but she wouldn’t lie down.

I used to say to her, forget it, this place, this time, it’s not for us, not for me and you. You walk down the street and what is this place, this place is a shambles, this place is a slaughterhouse, people a hundred years from now will look back on us and say “My God, how could they live like that?!”

Get Carter, Snatch

The alpha and omega of British gangster movies. The two could not be further apart in every way. Get Carter, from 1971, has a single protagonist, the structure of a revenge tragedy, an elegant, inexorable screenplay, gritty 70s realism, a palpable, Altmanesque sense of place, stunning, ferocious moments of brutality and ugliness, canny, closely-observed directing, and characters who are thinking, feeling human beings. Snatch has multiple protagonists, the structure of a screwball comedy, a ridiculously complicated screenplay bursting with incident and coincidence, flip 00s surrealism, action where even murder victims don’t seem to suffer, restless, anything-for-a-gag direction and a cast of screwy cartoon characters.

I dearly love both of them. When I can understand the accents, anyway.

My movie-going life crossed paths with Michael Caine during his “I’ll choose roles for the sunny locations” phase (beginning, I’d say, with The Swarm, continuing through Jaws: The Revenge and on to Dirty Rotten Scoundrels. This is Michael Caine during his “eminence for hire” era, and it’s easy to forget what an impressive, cold-eyed, nasty, mean little fucker he could be. He’s absolutely blood-chilling in Get Carter (and check him out in Mona Lisa as well, a dynamite script), a real cockney Samuel L. Jackson.

The script really helps. Everything is underplayed and unexplained. For the first half-hour, we’re not even sure who Caine is and what he’s doing. We know he’s some kind of London lowlife and we know he’s going to somebody’s funeral, but it isn’t until 25 minutes into the movie, when he suddenly picks up a fallen branch to knock a lookout man unconscious to we realize what kind of man we’re dealing with. We learn that the funeral was for his brother and that he didn’t die by accident, and we soon learn that Carter isn’t going to take his brother’s death in stride, and by the third act we almost feel sorry for the pornographers, gamblers and real-estate developers in his path, we cringe anticipating each savage remorseless, merciless encounter. We see him kick a car-door closed on a man’s head, grab another man by the genitals, throw yet another man off a seven-story car park. We see him drown a drugged woman, stab a man repeatedly in the gut and club another to death with a shotgun. We also get to see him engage in explicit phone sex (a cinematic first, I believe) while his landlady sits mere feet away.

Not that Carter is happy with himself, mind you. A good deal of his rage is directed inward as he knows that he, himself, is at least partly responsible for the death of his brother. He’s filled with turmoil and self-loathing and he plows through the underworld of Newcastle knowing that he’s never going to get back to London, he’s playing for keeps.

A lot of gangsters have passed into cinema history since Carter, but Snatch still manages to bristle with indelible portraits. The acting in Snatch is wonderful across the board, but two performances always stand out for me: Brad Pitt as the Irish traveler and Alan Ford as Brick Top, the gangster who feeds his enemies to his pigs. I’ve always enjoyed Pitt’s work, but his performance here is, I believe, without precedent. He’s game, lovable, fascinating and completely indecipherable, playing a character both utterly simple and yet utterly unknowable, and he positively inhabits the role, vanishes into it. It’s no star turn and no goof, he’s both playing the role straight and also performing it in the context of a comedy and you can’t take your eyes off him. This and Fight Club are his two best performances.

(I first saw Snatch in Paris [with Urbaniak and our wives, if you must know]: between the heavily-accented English and the French subtitles, we could almost make out what the actual plot of the movie was.)

When Alan Ford’s character first showed up, I first thought “Oh well, here’s another mean gang boss, I’ve seen this character a hundred times,” but Ford brings such a livid, seething intensity to the role that he’s breathtaking. I found myself actually scared of what he was going to do next, since there seemed to be no limit to his rage. Maybe it helped that I’d never seen Alan Ford’s work before (although he has a small role in Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels and has apparently done a lot of British television), I had no casting reference to fall back on (you know, the way we feel that it’s okay if Matt Damon kills someone in The Departed because we’ve seen him do it in The Talented Mr. Ripley but we freak when we see Henry Fonda kill someone in Once Upon a Time in the West because, damn it, he’s Henry Fonda, he’s not supposed to kill people!).

And, as different as the script for Snatch is from Get Carter‘s, I love the way the stories dovetail, I love tracing the plotlines from character to character and dive to dive, from madcap situation to madcap situation. If Richard Lester made gangster movies, they would probably be a lot like this. The scripts for this and two other Matthew Vaughn productions (Lock, Stock and Layer Cake) are, as far as I’m concerned, top-notch, intricate puzzle-boxes of narrative invention, Roman candles of collision and intrigue.

Screenwriting 101 — Finishing The Damn Thing

asks —

“I have about 100 different little ideas for themes, or characters or scenes, and I will start working on a screenplay and at about the beginning of the third act I get frustrated and what originally seemed to be a well thought out idea ends up seeming as if it falls apart and I will put it aside and start working on the next project. In all i have about 47 unfinished screenplays ranging from 1 page to 60 pages to about 100 and in total, i have finished two in my life; both for classes. Is this common?”

Yes.

But maybe deadline is not your problem. If your screenplay gets tied up in insoluble knots at the top of Act III, it may be because you didn’t plot it out well enough ahead of time. This is where treatments come in handy. They take a lot less time to write and they reduce the stress of writing the actual screenplay. If you’ve plotted the whole thing out ahead of time, the screenplay should be a simple filling in of the blanks.

I see that you have “about 100 different little ideas for themes, or characters or scenes.” What about story? David Lynch once said that writing a screenplay is easy, you just jot down ideas for scenes on notecards, and when you have 70 of those, you’ve got a feature. Well, David Lynch is one of the most imaginative, creative artists of our time but in this regard he is full of shit. You need a solid story before you start writing your screenplay, otherwise you are wasting your time, your screenplay will become a tangled mess by the end of Act II, justwhen it should be turning into an unstoppable dramatic juggernaut.

In fact, maybe it’s the second-act break that you’re getting stuck on. By the end Act II, the entire “problem” of the screenplay should be in complete focus and honed to its irreducible point. By the end of Act II, the protagonist should know who he is, what’s going on and where he needs to go to get to the ending, and then Act III should be how he gets there (whether he arrives at his goal or not is a different matter). At the end of Act II, Dr. Kimble has identified the one-armed man. At the end of Act II, the killer Brad Pitt’s been chasing suddenly turns himself in to the police. At the end of Act II, Clarice has her final confrontation with Lecter and he gives her the clue she needs to solve the case. If you’re arriving at the end of Act II and your script is suddenly falling apart, you may be structuring your acts wrong.

If you know how your second act ends but you don’t know what happens afterward, think of what you want the ending to be and write that. I do this all the time; there will be big spot in the script where I don’t know what’s supposed to happen, and instead of giving up I just type a row of X’s and skip to the next place where I know what’s supposed to happen. Or else write what we in Hollywood call “the bad version,” just the dumbest, most cliched version of events you can think of. Then at least you’ve got something written down and you can finish the thing and then go back, read it as a complete thing instead of a broken idea, and set about fixing it.

One thing I know: all writing is re-writing. If you don’t like re-writing you should not write screenplays. Early on in my career I had the good fortune to have a conversation with Scott Frank. I had just finished working on Curtain Call and he had just finished working on, I believe, Saving Private Ryan (I know, I know, he didn’t get a credit — this is the life we’ve chosen). I was carping about how often the producer of Curtain Call had made me endlessly re-write scenes and all I wanted was to have the damn thing done, and Scott said “Gee, that’s weird, I have the exact opposite problem, my scripts are always going into production before I feel like I’m done with them, I’ll see the movie in the theater and think ‘Man, if they had only given me one more day with that scene, I could’ve really made it sing.'” And he’s right — you have to enjoy the whole process and look forward to working on the script more.

Hope this helps.

My computer’s been sluggish.

Everything has been slow. Firefox, email, iTunes, everything. Plus, out of nowhere, it overheats two or three times a week.

I assumed it was just old, and had gotten filled up with a bunch of crap, as computers will. Little did I know the crap it was getting filled up with had come off my cats.

This afternoon, when it overheated for the second time in a day, I took the lid off, much as I would with the hood of my car, pretending I would be able to find something wrong. Well, the CPU was entirely covered in a snuggly blanket of cat hair and dust (pictured above).

They Might Be Giants at Walter Reed

From the liner notes for the 1997 They Might Be Giants album Then: The Earlier Years:

“The germ for Weep Day was the hyphenated reference to a song on the back of a Bob Dylan record jacket which read “Mr. Tambo-urine Man.” Flansburgh drew disturbing likenesses of both Mr. Tambo and Urine Man and Linnell dreamed up their antithetical relationship and set it to music.”

Another example of TMBG’s keen insight into national affairs. Here we are, years later, and we have our own real-life Urine Man, Army Surgeon General Kevin C. Kiley MD.

Who is this man and what is his destiny? Learn more…

Elvis vs. Elvis

These two songs came up on iTunes today, two of my favorite music stars ever, illustrating two approaches to writing songs about women.

Elvis C’s description of his subject is bitter, multi-layered, multi-dimensional and hyper-literate:

“So you began to recognize the well-dressed man that everybody loves

It started when you chopped off all the fingers on your pony skin gloves

Then you cut a hole out where your love-light used to shine

Your tears of pleasure equal measure crocodile and brine

You tried to laugh it all off saying “I knew all the time…

But it’s starting to come to me”

— Elvis Costello, “Starting to Come to Me”

While Elvis P’s view is more practical, topical and down-to-earth.

“And when I pick up a sandwich to munch

A crunch-a-crunchity-a-crunchity-crunch

I never ever get to finish my lunch

Because there’s always bound to be a bunch of girls”

Elvis Presley, “Girls! Girls! Girls!”

Screenwriting 101 — The Life of a Screenwriter

To those considering a career in screenwriting I offer the following statistics.

When an actor (Urbaniak, say) auditions for a movie, he must memorize a few pages of dialogue and go into the room with a clear idea of the character he’s portraying. When I audition for a movie, I must, essentially, write the entire thing before I go into the room. I must know who all the major characters are and have a handful of character beats that establish their personalities in a warm, human way, I must have a clear idea of not just the over-arching story but also the ins and outs of the scene-to-scene plot. I must invent every twist, reversal and revelation to give the thing thrust and excitement. I must, basically, see the entire movie in my head from beginning to end and I must be able to describe it, in the room, in a lively, entertaining, surprising way that meshes with that studios hopes for their production slate. Then, if I don’t get the job, I start the process all over with the next project the next day.

(Q: “why don’t you get the job?” A: For a lot of the same reasons an actor doesn’t — I’m just not what the studio is looking for. The problem is, often, that the studio doesn’t know what it’s looking for, and uses this audition process, in part, to hone its notion of what kind of movie it wants to make.)

I have been a professional screenwriter since 1994. In the ensuing years, I have written 25 or so screenplays. Of those, I’ve been paid actual money (and very good money at that, I hasten to add) for perhaps a dozen (the rest have been things I wrote for myself or for friends). For each of “actual job” or “money gig” (that is, a feature at a major studio), I create, typically, eight drafts, for which I get paid for four (courtesy dictates that one writes a draftfor the producer, incorporates the producer’s notes, then writes another for the studio).

So that’s all well and good. But then there are the treatments.

I cannot speak for other writers, but if I’m going to invent an entire movie I have to write at least a portion of it down on paper (by “paper” I mean, of course, a computer). For the plot to play out in a logical, consistent order I have to write it all out so I can go back, review,

amend, improve, edit, remove, etc. Basically, I write out the whole plot of the movie with notes regarding why this or that is important to the telling.

(The Writer’s Guild says that writers must be paid for treatments, but I have found that this is rare. What generally ends up happening is that I go in and pitch and the producer says “I like it, I’d like to think about it more, do you have something on paper I could look at to refresh my memory?” and the onus is placed on me to to be helpful for the good of the project. Personally, I don’t mind this practice because I think that my written words are a better presentation of my ideas than my fumbling, scattered pitch manner.)

I had a meeting with an old producer friend the other day and she asked me what old ideas I had kicking around. She specifically asked me to trawl through my treatments I’ve written for other projects, jobs I didn’t get, knowing that there are most likely some good ideas for movies in there. So I went through my files and found that I have, in the past dozen years, written 83 treatments. These treatments range from 10-page collections of notes and plot ideas to 50-page scene-by-scene descriptions. In some cases, I have written multiple treatments for projects, bringing the number well past 100. Creating these treatments is, in fact, how I spend the bulk of my writing life.

Of all these treatments, I have been paid for writing two; the rest have been created for the purposes of auditions.

So, to review: 12 years, 100+ treatments to get jobs writing 25 screenplays, of which I have been paid for 12, of which three have been turned into actual feature films (although there are perhaps a half-dozen others I’ve worked without receiving credit), of which one was an actual hit in-the-theaters movie (without which I’d probably be working at your local Denny’s).