Hail, Caesar! part 8

As Hail, Caesar! hurtles toward its climax, perhaps it’s worth taking a pause to note that this movie, which informs us that Hollywood lies, itself lies about the historical Hollywood.

Eddie Mannix, the reader may be surprised to learn, was a real person, who was the general manager of MGM under the real-life Nicholas Schenck. Mannix did “fix” a lot of MGM’s problems, from getting Clark Gable out of a hit-and-run accident to down-playing Garbo’s lesbianism. The real-life Mannix was also considerably older than Hail, Caesar!‘s, and was dead by 1963. While he was Catholic, there is no indication whatsoever that he was the quiet, soul-searching family man presented here.

While I’ve been saying that Hail, Caesar! takes place in 1951, there isn’t a date presented anywhere in the movie. The official plot description says it takes place in “the early 1950s.” I landed on 1951 primarily because that’s the latest date it’s conceivable to me that a group of communist writers would think up a plot as cockamamie as “kidnapping a movie star.” Baird Whitlock, meanwhile, is starring in a movie clearly modeled on Ben-Hur, which was not released until 1959. 1949’s Samson and Delilah started the “Technicolor Biblical Epic” craze of the 1950s, and Hail, Caesar! ATOTC seems to be a mashup of Ben-Hur and 1951’s Quo Vadis.

So, if 1951 is our benchmark, then Burt Gurney, who is clearly inspired by Gene Kelly, is making a service comedy-musical closely modeled on On the Town (1949). Kelly’s 1951 picture was An American in Paris. DeeAnna Moran, meanwhile, is obviously modeled on Esther Williams, who, like DeeAnna, had a complicated romantic life and made an “aquatic picture” titled Neptune’s Daughter in 1949 and Million Dollar Mermaid in 1952, not to mention Jupiter’s Daughter in 1955 and Athena in 1954.

But, as noted earlier, a 20-something singing cowboy would be seem very old-hat to 1951 audiences, so Hobie Doyle is a puzzling anachronism. Even more so, his date at the Lazy Ol’ Moon premiere, Carlotta Valdez, is clearly modeled on Carmen Miranda, who was 41 years old in 1951, long past her peak and four years away from her untimely death. It seems that Hobie and Carlotta belong to a decade of movies set at least a decade earlier than Whitlock and Gurney. It’s as though Eddie Mannix’s entire career is being packed into one night.

Hail, Caesar! part 7

Eddie heads back to the Chinese restaurant to meet, for a second time, with Cuddahy, the man from Lockheed. What has changed in Eddie’s life in the past six hours? He’s had to deal with a director throwing a hissy fit, he’s had to pay ransom for a kidnapped movie star, figure out a solution to a pregnant mermaid problem, fend off fights from two gossip columnists, and save the life of an editor who was almost killed by her own Moviola. That has involved a lot of running around but nothing that Eddie would call “physical culture.” Cuddahy offers Eddie a contract of ten years, with stock options. He’s essentially offering Eddie a chance to be “set for life,” a sense of permanence in a world full of craziness. He also offers Eddie a set of airplane gifts for his children — he knows that Eddie’s 27-hour days leave him no time to be a husband and father, and that wracks him with guilt.

Hail, Caesar! part 6

At the half-way point of the narrative, Hail, Caesar! introduces a new major character, Burt Gurney, seen on the set of a service-comedy-musical, performing a long, complex tap routine with a group of sailors, to a song called “No Dames.” In the context of the number, Burt and his crew are going to sea for eight months and will be without women and with little to do. Gay joke aside, the number is nevertheless a piece of foreshadowing for Burt’s eventual fate, a sunny Hollywood version of a story that hasn’t happened yet. There is no biblical subtext to the number that I can divine, but Hail, Caesar! doesn’t seem to be that adamant about laying on the Christian symbolism too heavily. Hobie Doyle’s movie, for instance, has no biblical subtext either, beyond a kind of Manichean good-guy-bad-guy reading of human interactions. Like Hobie’s movie, and DeeAnna’s mermaid picture, the “No Dames” sequence relishes the pure visual joy of bodies in motion, shifting patterns and colors.

(Also like the other movie-within-a-movie scenes, “No Dames” is presented as though being shot in sequence, live on a soundstage. In this way, Hail, Caesar! becomes a movie about itself, a movie that lies to us about how movies are made while on the way to telling us about how movies lie to us.)

Hail, Caesar! part 5

After Eddie collects the $100,000 in ransom, before he can make it back to his office he runs into Thora Thacker’s identical twin sister Thessaly, who, like her sister, intends to run a story on Baird Whitlock, this one about his current disappearance. Eddie asks both sisters “What kind of a name is _____?” Well, “Thora” is, of course, a Scandinavian name, the female version of Thor. “Thessaly,” on the other hand, is a city in Greece. Both civilizations, and names, predate Christianity. Perhaps the Thacker sisters (“Thacker” being a corruption of “Thatcher,” or “the guy who builds roofs” in Old English, also derived from the Norman) are meant to be reactionaries, students of “the old ways,” predating even Caesar’s Rome, who are resistant to both Mr. Schenck’s Capitol and to the message of Jesus.

Hail, Caesar! part 4

Eddie Mannix meets with the producer of Hail, Caesar! ATOTC to discuss the crisis of Baird Whitlock’s disappearance. The producer is, if anything, even more passionate about the project than Eddie. He’s not prepared to “shoot around” Baird, the “heart of the movie” depends on Baird’s face, his star power. And so a ticking clock is installed in Hail, Caesar!: Eddie must find and recover Baird Whitlock by tomorrow morning or else his tale of the Christ is forfeit. (I find it hard to believe that a project the size and scope of Hail, Caesar! ATOTC hasn’t already been beset by massive delays and cost overruns, but apparently Eddie Mannix runs a pretty tight ship.)

Hail, Caesar! part 3

Eighteen minutes into Hail, Caesar! we are treated to a water ballet number from another one of Capitol Pictures’ production slate, Jonah’s Daughter. The sequence is quite long and involved, with dozens of synchronized swimmers, a mechanical whale and Scarlett Johansson in a mermaid outfit. Hail, Caesar! takes care, when presenting its movies-within-the-movie, to present the finished product, as though complex sequences like the one shown here or the shootout in the Hobie Doyle movie are shot live by multiple camera. The Coens are careful to save their “cutting to reality” jokes for key moments; they otherwise give these Technicolor spectacles their due, letting us luxuriate in the tactile thrills of their sumptuous production values. Which makes me think that the title, Hail, Caesar!, isn’t meant ironically; the Coens really intend their movie to be a heartfelt salute to “capital” and the colorful fantasies it provides for the people.

And although the title of the mermaid picture is only fleetingly mentioned in an earlier scene, the whale is very much present, and we are reminded that the tale of Jonah and the whale is, like Hail, Caesar! ATOTC, also from the Bible, although from the Old Testament, the one with the “angry God” mentioned in the scene with the religious leaders. So an examination of the story of Jonah is in order.

From Wikipedia:

Jonah is the central character in the Book of Jonah. Commanded by God to go to the city of Nineveh to prophesy against it “for their great wickedness is come up before me,” Jonah instead seeks to flee from “the presence of the Lord” by sailing to Tarshish. A huge storm arises and the sailors, realizing that it is no ordinary storm, cast lots and discover that Jonah is to blame. Jonah admits this and states that if he is thrown overboard, the storm will cease. The sailors try to dump as much cargo as possible before giving up, but feel forced to throw him overboard, at which point the sea calms. The sailors then offer sacrifices to God. Jonah is miraculously saved by being swallowed by a large whale-like fish in whose belly he spends three days and three nights.[3] While in the great fish, Jonah prays to God in his affliction and commits to thanksgiving and to paying what he has vowed. God commands the fish to spew Jonah out.

How extraordinary that Eddie Mannix is producing a movie inspired by this story. Jonah is told by God to go preach to Ninevah, but doesn’t think he’s up to the task and flees from God’s command. God answers his reluctance with a storm, but then offers him salvation with a whale. In Eddie’s world, we see no indication of his fleeing from his God’s (Mr. Schenck) command, but we do see him terribly worried about disappointing Jesus (even though he doesn’t know a lot about Jesus). I think Eddie is a man who feels that he should be devoting more attention to God, but instead spends his time in activities of desperately earthly nature, even though he himself has only one vice, cigarettes.

Hail, Caesar! part 2

If Nick Schenck is the “capital” of Hail, Caesar!, I think Hobie Doyle, the singing cowboy western star is it’s “little guy.” Hobie is naturally gifted: he can ride a horse and rope a steer, and he has effortless charm and slinky good looks. Hollywood has made him a star, but he has no affect whatsoever — what you see onscreen is exactly who he is. That’s an important distinction, because, alone among the actors presented in Hail, Caesar!, Hobie doesn’t put on airs, doesn’t wear a disguise, isn’t manufactured. He’s the genuine article. He feels lucky to be where he is, lucky to be in pictures, lucky to be famous, and lucky that he’s got people like Eddie Mannix looking out for him.

Hobie is unique among Coen Bros “little guys,” because later in the movie we’ll meet a group of people who believe themselves to be little guys but are not. In many ways, Hail, Caesar! is like a sequel to Barton Fink but told from the other side of the studio executive’s desk. That may, perhaps, signal a change in the Coens’ perspective; once critical of capital as Hollywood outsiders, now they have a more nuanced approach as Hollywood titans — capital, they seem to think now, is just as human as the little guy. (It’s worth noting that True Grit, the Coens’ first and, so far, only blockbuster hit, was also their first screenplay where “capital” is also the narrative’s protagonist.)

Hail, Caesar! part 1

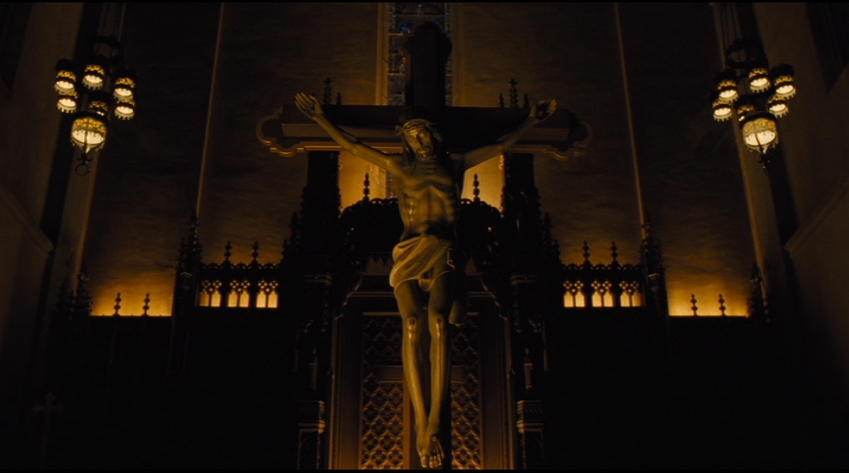

Hail, Caesar! begins with the image of a crucifix. This is imn portant to note, even before we know anything about the story, because it defines the poles of the narrative: the movie is titled Hail, Caesar! but Jesus is the opposite of Caesar. (As the gospels say,”Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s.”) The movie, we will soon learn, is about a protagonist constantly running from Jesus to Caesar and back again, forever unsure about which one he’s serving.

All Coen Bros movies are, on one level or another, an examination of capitalism. There is always a character who represents “capital,” that is, the guy with all the money, and there is generally a character who represents “the little guy,” that is, the working Joe who’s just trying to get by. And the story of Jesus, as it happens, begins with the character who represents “capital” maybe more than any other in history, Caesar, raising taxes. Caesar raises taxes, which necessitates a census, which brings Joseph and his wife Mary from Nazareth to Bethlehem, and there’s no room at the inn because everyone is in town for the census. The boy who is born in a manger because of taxes eventually grows up to be a threat to Roman peace in Jerusalem. That’s the so-called “greatest story ever told,” and the protagonist of Hail, Caesar! is a storyteller.

NAMCAR Night Race

It's here. The NAMCAR Night Race Trailer. #TVMA #NASCARonACID #slotcarracing #comedy

Posted by NAMCAR Night Race on Wednesday, June 22, 2016

When I was a young man in the 1990s, creating experimental theater pieces in downtown New York, John Leguizamo and his producing partner David Bar Katz, for no good reason, gave me a job working on their sketch-comedy show House of Buggin.’ The rest of the writing staff was honest-to-goodness sketch-comedy professionals, and I was some weirdo who was thrown into the mix. One of those professionals was Lance Khazei, who, I recently learned, has now created his own mind-bending piece of TV-land hysteria, NAMCAR Night Race.

NAMCAR Night Race is a show about people who are way too into slot-car racing. NAMCAR (North American Model Car Races), in the world of this seriously bent half-hour, is a kind of shadow-realm of NASCAR, but more intense, because the stakes are so very very small. Like The Wacky Races, there is a cast of more-or-less insane drivers who, for various reasons, can’t stand each other. All have the desperate need to prove themselves out on the track, except, of course, that they can’t fit on the track, and the track would fall down if they tried.

The comedy is presented in a mock-sports-show format, but then that’s where the real world ends. Like NASCAR crossed with “Too Many Cooks,” the race-car-driver narrative will take sudden, bizarre left turns. An interview will suddenly turn into a sketch, which will then turn into a commercial, which will then melt down and explode into a graphics assault, all without warning, before suddenly swinging back around to the sports-show format. There is a narrative in there, but it unfolds in a kind of impressionistic Bugs-Bunny dream frenzy. Like Monty Python or Mr. Show, it’s impossible to predict what’s going to happen from moment to moment, only that it’s going to be weird.

And yet, the show also bristles with humanity. While there are characters who might suddenly shoot lasers out of their eyes without warning or imagine themselves to be robots from the future, the struggles that the racers have are as simple and direct as can be. One racer, Scout, is a homespun tomboy Dixie Chick who wants to reclaim her father’s legacy. She also has eyes for likeable dude Manny, who only has eyes for Pit Girl, who is a man-eating succubus who also spends a lot of time thinking about Lego figures. You see what I’m saying – just when you think “Oh, I get what this show is,” that’s not what the show is. The co-hosts, D’Arcy Fellona and Theo Von, are as likely to bicker about who’s forgotten to take their meds as they are to describe the race unfolding, and every one of the characters is prone to hallucinations. Interviews devolve into digressions on Jenga and Paula Abdul, HO-scale figures on the track unexpectedly come to life, and third-prize winners in the race receive a year’s supply of ransom notes. It’s a demented spin around the NASCAR track and a breath of fresh air to comedy TV.

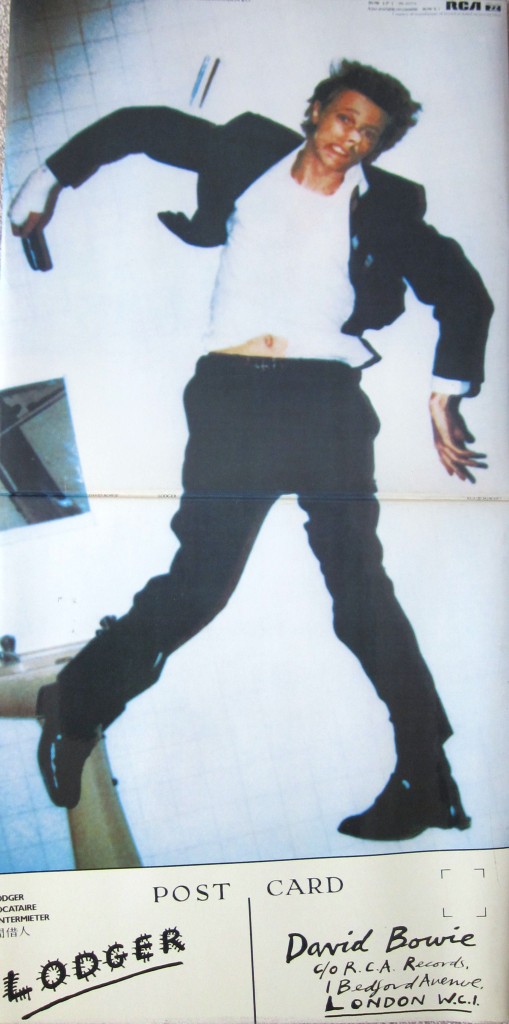

David Bowie: a personal history

It was the spring of 1979. I was 17 years old and, since it was a Tuesday afternoon, in a record store. I was into Elvis Costello and Talking Heads and I was looking for other “New Wave” records to change my life. I saw, up on the shelf, Lodger, the new album by David Bowie, pictured above.

Look at that cover. That was the cover of an album by a major artist on a major label. I saw that cover and thought: “Huh. That’s weird. What the hell isthis?” To put the cover of Lodger into context, here are some other albums I might have seen in that record store that day: this, this, this, this, this, this, this, this and this.

The cover of Lodger was, in fact, so strange and mysterious that it spooked me a little. It was printed sideways and backwards, for one thing, with the image wrapping around the side of the gatefold, and the record top-heavy in the front pocket rather than weighing down the back. Everything about it was wrong, weird, fucked-up. I put David Bowie in my list of “artists to keep an eye on” and moved on to, probably, this.

A year or so later, David Bowie turned up, in Chicago (I was living in nearby Crystal Lake), performing in a run of the hit play The Elephant Man before taking over the title role on Broadway. As an aspiring 18-year-old playwright, I was primarily excited about seeing a genuine “Broadway play,” the fact that pop-star David Bowie was in the show was a secondary concern.

Well, the show was great, and Bowie was great in the part, and his first appearance on stage was as he appears in the second image above: naked but for a loincloth, his body way too thin and way too pale, as if the baby Jesus had been caught in a taffy-pull. I’ve been told that the part in The Elephant Man is “actor-proof,” but that didn’t detract from my enjoyment of Bowie’s performance as he mimed John Merrick’s illness and distorted his voice to approximate the sound of a man with a head full of bulbous bone growth.

So this David Bowie fellow suddenly became very interesting to me. And he had a new record out, Scary Monsters, which had a cover almost as weird and fucked-up as that of Lodger. I snapped it up at my local record boutique, took it home and dropped a needle on it.

Well.

The Buddhists say that when the student is ready, the teacher will appear, and Scary Monsters was exactly the record I needed to hear in the summer of 1980. At this point, I was living in a trailer in southern Illinois, in a neighborhood where, no kidding, an 18-year-old kid could get beaten up for listening to David Bowie. Or for listening to anything to the left of this.

Scary Monsters had everything: huge amounts of weirdness, oddly tuned guitars, plenty of jarring, unsettling effects, great passion juxtaposed with jaded disaffection. It was, yes, scary and super, monstrous and creepy.

The following three years involved me soaking up everything Bowie had done up to that point. He became the center of my musical universe — he went to Africa before David Byrne or Peter Gabriel did, he worked with Robert Fripp and Brian Eno before Talking Heads did and hired Adrian Belew before Talking Heads did too, for that matter. His records swerved all over the place from weird and arty to weird and poppy to weird and soulful to weird and blistering. I rarely believed a word he sang, but sincerity somehow seemed beside the point — underneath and alongside the layers of irony and pose, covered over and thrown into relief by incident and marketing, the “message” in Bowie somehow always was located somewhere outside the lyrics. Now, the day after his death, I’m finding more and more that Bowie’s distance isn’t as distant as I first thought — his lyrics are sometimes oblique and confounding, but just as often they are solid emotion wrapped in technique.

In the midst of my obsession, 1982, I acquired my very first cat. There was no question what he would be named: Bowie was my avatar, my polestar, the banner of my identity.