The Big Lebowski and our present moment

I’ve been thinking about The Big Lebowski a lot recently, specifically this line from Walter Sobchak, the gun-toting, conspiracy-loving, live-wire, converted-Jew Vietnam vet. “Say what you want about the tenets of National Socialism, at least it’s an ethos.”

Walter, in the moment, is complaining about the German nihilists who have been bedeviling his friend The Dude, but the line gets me thinking about Jeffrey Lebowski, the “Big” Lebowski of the title. Jeffrey Lebowski is a local plutocrat who sets the mystery plot of The Big Lebowski by hiring The Dude to help recover his kidnapped wife Bunny. In the tradition of American noirs, things are not as they appear. Specifically, (spoiler alert) Jeffrey Lebowski is a fraud. He’s not wealthy, he’s a desperate embezzler who is using his wife’s disappearance to steal a ton of money from his family’s foundation.

Does that sound like anyone we know?

Jeffrey Lebowski likes to lord his wealth over people and pretend to be a big shot. “Your revolution is over, the bums lost!” he bellows at The Dude, advising him to “get a job.” Lebowski, of course, has no job of his own, he’s been living on his family’s wealth all his life.

Which brings me back to our President. Donald Trump could have been a Jeffrey Lebowski, whiling away his time in his mansion, living off the interest of his inherited wealth, but he had to be a big shot. He just had to be, he couldn’t live otherwise. He had to put his name on a thousand buildings, in letters as big as structurally possible, and put his face in front of every camera in sight. Unfortunately for all of us, he’s a bona-fide mouth-breathing idiot, a devastatingly stupid businessman who has never had a success in his life.

As a liar, con-man and thief, Donald Trump lives in constant desperation, terrified that, at any moment, he will be unmasked, that people will learn that, like the big Lebowski, he’s a tiny man in a big house, a blustering fool who blames his threadbare soul on everything but his own actions, actions he made while possessing every possible advantage available in his society.

And so he’s destroyed the foundations of an entire country, turned an entire government into a criminal enterprise, replaced a generation of civil servants with toadies and sycophants, not out of any ideology whatever, but simply to cover up his crimes, which escalate exponentially with every passing hour. Our nation is being demolished not from a fiendish plot toward fascism but to distract from the crimes of a single man.

Say what you want about the tenets of national socialism, at least it has an ethos. Or, as Rick and Morty put it, “You’re like Hitler, but even Hitler cared about Germany, or something.”

Some thoughts on The Lion King

UNPOPULAR OPINION: The Lion King is actually really good.

I was not looking forward to seeing this movie, I wasn’t even particularly interested in it. I had seen the 1994 movie, of course, and had analyzed it in depth when writing Antz in 1996. I’ve seen the Broadway show, which is wonderful. So I’m pretty familiar with the material, I didn’t think it would be necessary to see this new version. But I found myself in Hollywood with a few hours to kill while waiting to pick up my daughter, so I thought, what the hell, I’ll go see The Lion King.

The reviews that I’ve read complain about the characters’ lack of expressiveness and the lack of spectacle in the musical numbers. And yes, the decision to make the animals look, and behave, like real animals, obviates the question of Broadway-style show-stoppers and dancing giraffes.

So the challenge before the director, Jon Favreau, is to match, or top, the energy and beauty of the original movie while keeping one cinematic hand tied behind his back, as it were. And I have to say, he succeeds beautifully.

I didn’t find the characters unexpressive at all. Me, I generally find the performances of animated characters WAY over the top, every emotional i dotted to death, with bugging eyes, smirking mouths, bobbing shoulders and gesticulating hands. And yes, real animals don’t do any of those things. But it is not true that real animals aren’t expressive. Just around our own houses, we find animals expressing themselves in both obvious and subtle ways, fear and excitement and trepidation and boredom and anger, and we have no problem reading their expressions. And so it is here. The Lion King, like the Jungle Book adaptation before it, also directed by Favreau, substitutes the “cartoonish” expressions of its characters with real-life animal expressions, and I found it fascinating, because the characters are SO realistic, and so well-observed, that the design logic — real animals acting out a carefully-contrived script — got under my skin super fast, and I found myself seeing animals, hundreds of animals, thousands of animals, as though I’d never observed them before.

The thing is, there’s a tradition of this in Disney animation. Before Timon and Pumbaa did their vaudeville act, Disney animation, from Bambi to 101 Dalmations, was very much about observing the real motions and behavior of real animals. When you watch Bambi, it’s remarkable how much drama and pathos Disney wrings out of the common behaviors of deer. When you watch Lady and the Tramp, it’s as though Disney is sitting beside you saying “Look, a Cocker Spaniel, have you ever seen anything like it? How awesome is that dog?” The magic of Disney’s classic animated features is that, by putting its animals in their contrived plots, it allows us to see those animals as though we never have before.

And so it is here. When the young Simba takes a hesitant step back from a threatening Scar, we see a real lion cub reacting to a real threat. When Pumbaa sticks a hind hoof in his ear while distractedly answering a question, it’s a real warthog we’re seeing behaving in a real way. Favreau has taken the place of Disney, sitting beside us, saying “Look, a meerkat! How awesome is that?”

And so a “production number” like “I Just Can’t Wait to be King,” while it does not have a pyramid of dancing animals, it DOES have Simba romping through the Savannah, with all the actual, true, real spectacle of all the wildlife there, building and building in its multiplicity and complexity, and, while we don’t get Broadway glitz, we DO get a thrilling, exalting, satisfying spectacle of the actual natural world. It’s a real achievement in moviemaking, and I’m rather baffled that more people haven’t seen it that way.

Piece in The Guardian

Well folks, here I am with my graphics pieces in The Guardian. I’ll be the first to admit, this is weird.

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

Thank you to my faithful followers who have been waiting patiently for my analysis of The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. You’ll have to wait a little longer, but, for those who want a short, sharp, incisive overview, this video is an excellent place to start.

Kubrick book

Hey folks, my new book on Kubrick, gathering my analyses of Dr. Strangelove, 2001: A Space Odyssey, A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon and The Shining is now available where finer books are sold (meaning: Amazon). Pick up a copy for your electronic device, or, if you like paper things, it’s available as a paper thing!

Kubrick: Barry Lyndon part 9

Scene 92-96. Barry’s plans for becoming a gentleman have come to nothing. He still lives in a nice house, still has access to money, still has a beautiful wife (who apparently loves him more than he deserves) but he will never be a true gentleman. His violent streak — that is, his tendency to deliver violence on his own terms, rather than through money or an intermediary — has put an end to that dream forever.

Without social advancement, what does he have left? The answer, oddly enough, is “love.” Barry loves his son Bryan with great abandon. We’re treated to the longest “montage” yet in Barry Lyndon — five scenes of Barry interacting with Bryan and being a loving, indulgent father. He fishes with him, reads to him, teaches him how to fence, plays croquet with him, and takes him horseback riding. The narrator deepens the images with background on how Barry feels about the boy, and also spoils their love by announcing that the boy is doomed to die young.

There’s another way to read the montage, of course — Barry wants social advancement, and he threw that chance away when he kidney-punched his stepson in a packed recital hall. So in order to achieve the gentlemanly status he craves, he employs the oldest trick in the book: he chooses to achieve his goal through his progeny. And while that reading is more cynical, it also indicates that Barry, at this stage of his life, has at least begun to think outside himself, to understand life on a more cosmic level, to see himself as part of a continuum.

Kubrick: Barry Lyndon part 8

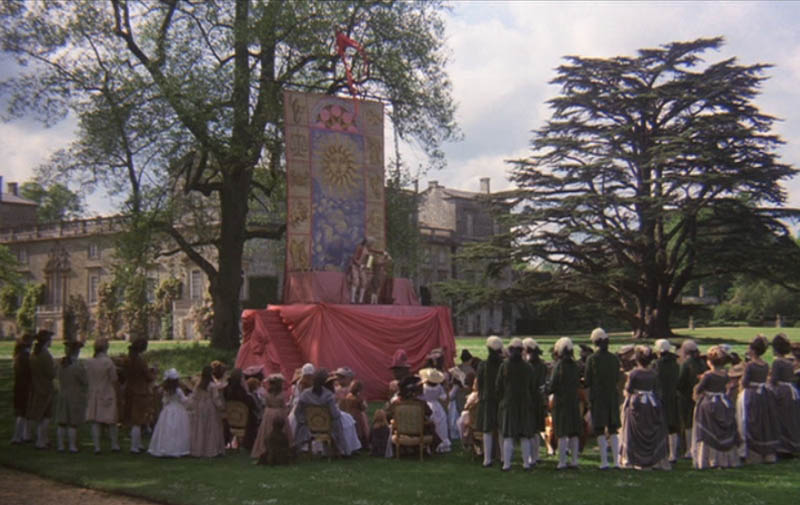

Scene 75. As Act VIII of Barry Lyndon begins, we’re treated to a rare explicit time jump. Barry’s son Bryan is now 8 years old and is, it appears, a very happy little boy. Lord Bullingdon, meanwhile, has grown from an anxious little boy to an anxious young man, still sitting at his mother’s knee, still holding her hand, now wearing the white makeup and powdered wig of his station as a young lord.

The scene is Bryan’s eighth birthday party, and all of Lady Lyndon’s friends are there, as well as Barry’s mother. Barry, we could say, has arrived. He’s got access to wealth, he’s got wonderful social status, he’s got a beautiful wife whom he treats terribly, he’s got loads of friends and he’s having sex with every lady who meets his gaze.

Appropriately, the scene illustrating this is a magic show. A magician performs routine sleight-of-hand and conjuring tricks for Bryan as the crowd smiles and applauds, and we’re reminded that Barry’s life is a kind of magic trick of its own. Deception, trickery, showmanship and style got Barry where he is, and the deeper suggestion of the narrative is that everyone there at the party, indeed, everyone in the movie, has achieved their social status through some combination of thuggishness, trickery and deceit.

Kubrick: Barry Lyndon part 7

SCENE 63. We come back from intermission to find a title card announcing that the remainder of Barry Lyndon will be about Barry’s fall from good fortune. The first part of the movie — the first six acts — were about Barry’s rise to wealth and power, and the second part will concern his undoing.

That would make Scene 63, which shows the wedding of Barry to Lady Lyndon, dramatically, the pinnacle of Barry’s joy. He’s gone from being a love-sick middle-class goon to being married to a genuine capital-L Lady. He’s been re-born a number of times so far in the movie, but the wedding is the moment where he has finally, he feels, entered into his true domain: a gentleman of wealth and taste.

We see Barry’s allies in attendance at his wedding: the Chevalier de Balibari and his mother are both there lending their support. If Barry’s mother sees anything untoward in her son’s marriage, she doesn’t show it: she, too, seems to feel that she has finally entered her proper sphere at the mother to a gentleman of wealth and taste.

Reverend Runt performs the ceremony, and Kubrick gives special emphasis on the nature of marriage among nobles in 1773. Marriage, says Runt, is what saves humans from acting “in carnal lust, like brute beasts,” and that marriage is something to be entered into “soberly, and in the fear of God.” We can almost see Barry’s smirk — he’s seen enough of life in the Seven Years’ War to know that men are brute beasts, and enough injustice to know there is no God.

Where are our themes now? Runt addresses violence in its absence, Barry has reached the pinnacle of his social climb, and love, we are meant to gather, is nowhere in evidence.

The scene also suggests the question, what does Lady Lyndon want out of this? Does she think Barry is actually a gentleman, or has he merely succeeded in flattering her to the point where she doesn’t care? As the narrative progresses, her son Lord Bullingdon (here seen staring daggers at Barry during the wedding ceremony) routinely accuses Barry of being, well, of being who he is: a base-born Irish social climber. Lady Lyndon’s husband Charles bellowed the same thing, so it’s hard to imagine that the thought never crossed the Lady’s mind. On the other hand, Lady Lyndon is still young, and, based on the evidence, did not have a satisfying sex life with her husband. The narrative does not say, but one wonders how Lady Lyndon ended up married to Charles in the first place. They have an 11-year-old son, so she must have been quite young when she was married off to Sir Charles. Maybe she was traded to Sir Charles by her own father, who was a social climber much like Barry. Maybe she knows, to some extent anyway, who Barry is and what a fraud he is, and accepts him on face value. In any case, suffice to say, the movie does not dig very deep below the surface of Lady Lyndon’s motivations: she remains, almost entirely, a porcelain doll in a gilded case.

Kubrick: Barry Lyndon part 6

SCENE 54. Barry Lyndon now enters its sixth act. Barry has been a love-struck goon, a British soldier, a fugitive, a Prussian soldier, a Prussian spy, and is now reborn, again, as a high-society gambler. We now find him at the side of his third surrogate father, the Chevalier de Balibari, as he practices his trade of cheating at cards.

How do we feel about Barry now? We’ve just smiled at him and the Chevalier pulling the wool over the Prussians’ eyes with an Ocean’s 11-level switcheroo. Now we see him, with white-powdered face and ultra-fancy dress, helping the Chevalier con a lord who is portrayed as a simpering, preening idiot. It feels to us like Barry has gotten a leg over this business of social climbing, and if he did so by being a liar, a cheat and a thief, well, we’re okay with that, because those rich snobs deserve what they get.

Where are our themes? Well, the narrator informs us that Barry has decided, now and forever, to live life as a gentleman, and he’s now at a gaming table in a royal court, so that’s our theme of social advancement. “Living as a gentleman,” of course, means lying and cheating, which is one of the more trenchant observations of Barry Lyndon. Love enters the scene in the form of Lord Ludd, who is playing against the Chevalier under the handicap of being distracted by numerous comely young royal personages, literally nibbling their fingertips fielding multiple kisses and whispered comments while trying, not very hard, to concentrate on the game, so distracted that he misses the oldest trick in the book, the Chevalier producing a card from up his sleeve. As for violence, Kubrick puts it in the cut as this scene sets up the violence and the next one pays it off.