Idiocracy

This movie hit me with a force I was quite unprepared for. I have little intelligent to say about it at the moment (ironically enough), but I’d like to do my part to get people to see it.

Once in a great while, a movie has a vision so thorough and detailed that it alters the way the world outside the theater looks. The last time it happened to me was Batman in 1989; after two hours steeped in Tim Burton’s vision of Gotham City, with its corruption and decay and facsist architecture, I couldn’t walk the streets of New York that summer without half-expecting to see the Batwing fly overhead.

It happened again tonight with this movie. The basic concept (people are loud and stupid) couldn’t be more simple, and yet this movie takes it to such a relentlessly high degree that it becomes difficult to shake off. Idiocracy is a vision of America so specific, so obvious and yet so unique and so detailed, it was impossible for me to walk out of the theater without hearing people talking in its language, moving to its rhythms and acting according to its principles.

I’m not even sure what to compare it to. Structurally it reminds me of Sleeper; both movies put a self-described “average guy” into a dystopian future, and neither movie has a well-engineered plot. But after that I start to run out of points of comparison. If Clockwork Orange had been conceived of as a comedy, I suppose it might have turned out something like this, but that’s about it. Suffice to say, it’s not like Beavis and Butt-head and it’s not like King of the Hill and it’s not like Office Space. In fact I would say it’s like nothing you’ve ever seen before, and how many movies can you say that about these days?

Venture Bros: Fallen Arches

Often I will watch an episode of Venture Bros more than once to catch the asides and subtexts; this is the first time I had to watch it twice just to sort out all the plot strands.

In your typical well-written 22-minute TV episode, there will be an “A” story and a “B” story, ie: Homer quits his job while Lisa works on a science project. Often the two stories will link up towards the end of the episode, but not always.

In “Fallen Arches” I found an “A” story, a “B” story (with its own sub-plot), a “C” story, a “D” story, an “E” story and, incredibly, an “F” story.

The “A” story is: Dr. Orpheus has, for some reason, vaulted from the backwaters of “down-on-his-luck necromancer with no job renting Rusty’s garage” to “leader of superhero team with his own private island.” Apparently he, like Rusty, was once quite the thing, but, like many men, found himself burdened and diminished by marriage, fatherhood and responsibility. Wife gone (why is unclear, although at this point of the show literally anything is possible) and daughter of age, he suddenly “qualifies” for an arch-villain, to be supplied by the Guild of Calamitous Intent. (Why the Guild exists, how it operates, and why Dr. Orpheus suddenly qualifies is unclear, but I’m sure time will tell.) He gathers up the members of his old team, The Order of the Triad, and auditions arch-villains.

The “B” story, I would say, is Rusty and his Walking Eye (glimpsed in the season 1 titles, it now has its own plot-line). He’s built a useless machine and is bitterly frustrated when no one recognizes its brilliance. Rusty also takes time out (because the episode is, apparently, not plot-heavy enough) to chat with Dean about the birds and the bees, a chat that leaves neither one any more enlightened than before.

The “C” story involves the Monarch’s Henchmen and their attempts to, on what apparently is a slow day in Monarch-land, branch out into supervillainy themselves. Comedy ensues.

The “D” story involves a homely prostitute and her sad misadventure at the hands of The Monarch, who, after receiving his pleasure (whatever that is), turns into some kind of Thomas Harris villain on her and forces her to undergo a series of life-threatening tests in order to leave his cocoon. An Edgar Allan Poe quote is thrown in for good measure.

The “E” story involves Hank and Dean solving the Mystery of the Bad Smell in the Bathroom (and the disappearance of Triana).

The “F” story involves Torrid, who looks like a cross between Deadman and Ghost Rider, his misadventure in the bathroom and his attempts to impress Dr. Orpheus and Co., bringing the plot full-circle.

The title is “Fallen Arches” but it could have just as accurately been “False Impressions,” as each character in the episode is trying to impress someone, and often failing. Rusty wants to impress his family with the Walking Eye but fails, so instead tries to impress the Guild creeps auditioning for Dr. Orpheus instead. This works to some degree, but not without Rusty debasing himself with his Whitesnake-music-video/Tawny Kitaen “washing the car” vamp. And finally Rusty must face the fact that he has impressed no one in his house, that his inventions, his career and his life is a failure, even while Dr. Orpheus is in re-ascendency. The auditioners are desperately trying to impress Dr. Orpheus and company, and mostly desperately failing. The Henchmen want to impress some ideal, invisible female and get nowhere near even failing. The Monarch wants to impress the prostitute and does, in a way, but probably not in the way he’d like to. Dean wants to impress Triana but fails to even get her attention, although he does succeed in impressing Hank, later in the show, with his ability to actually solve a mystery. Finally, Torrid succeeds in impressing Dr. Orpheus by kidnapping his daughter, although how exactly he accomplished that, and how she ended up on Dr. Orpheus’s private island, is left unclear. I’m unfamiliar with Lady Windermere’s Fan but I’m willing to bet its plot revolves around someone trying to impress someone else too.

Who is not trying to impress anyone in this episode? Well, Brock is perfectly comfortable in his skin and doesn’t care about impressing Dean with his abilities to deliver Wilde. He’s just as happy to kill Guild villains in a tux as he was to kill them while naked a few weeks ago. The prostitute doesn’t seem too concerned about impressing the Monarch although she gives it the college try. Dr. Orpheus’s team seems quite self-effacing and comfortable with themselves, and Dr. Orpheus, with his newfound status as superhero, himself seems more confident and relaxed in this episode than ever before. Triana, of course, is a goth chick and so is genetically incapable of trying to impress anyone. Sadly, Dr. Girlfriend is briefly reduced to trying to impress Dr. Orpheus as the hastily-considered Lady Au Pair. It doesn’t take much for her to regain her self-esteem however, Jefferson Twilight’s mention of her deep voice is all it takes.

Any one of these plot lines would have been enough for most shows. This episode had the breathless pace of the Christmas special but was twice as long. It makes me wonder, aloud, what a Venture Bros feature might be like. Could this kind of pace be sustained over 90 minutes? Would there be 18 different plot lines? Would it be like It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, but funny, and short?

The Guild exists, apparently, because all superheroes require an arch-villain. Otherwise how would we know they’re heroes? It wouldn’t surprise me to learn that the Guild is financed by superheroes themselves. My son Sam understands the concept and he can’t even read; he knows that Dr. Octopus fights Spider-Man, Mirror Master fights The Flash and Sinestro fights Green Lantern. When he sees a character he doesn’t know, before he asks “What does he do?” he’ll ask “Who does he fight?”

Reagan understood that every superhero needs an arch-villain, and so does George W. Bush, although Bush made the poor decision to go for the “better Bad-Guy Plot” instead of going after the real villain. The American people have begun to understand that if you’re Superman, you fight Lex Luthor, not the Mad Hatter.

Lucky 1994-2006

1. Lucky at eight weeks, 1994

2. Lucky at six months, 1995

3. Lucky this morning

4. Drawing by Sam for Lucky “to take with him:” it features a drawing of Lucky both as a kitten and as he was this morning, Sam smiling at him to cheer him up, a tuna fish, and a “surprise for later.”

Pop Quiz

What do Samuel Beckett, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Paul Michael Glaser, Rock Hudson, Angie Dickinson, Al Pacino, OJ Simpson, James Garner, Steven Spielberg, Michael Landon, John Houseman, Robert Redford, Oliver Stone, David Lynch, Will Smith and Bryan Singer all have in common?

THE ANSWER:

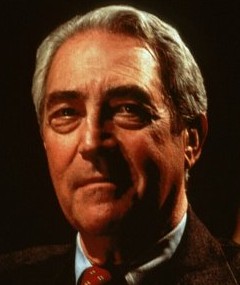

All of them did projects with one of my favorite character actors, James Karen.

With 164 credits to his name, James Karen was a Hey! It’s That Guy! when JT Walsh was still in short pants.

One of his first credits (after episodes of Car 54, Where Are You? and The Defenders) was to appear in Samuel Beckett’s 1965 Film, a baffling whatsit from the soon-to-be Nobel Prize-winning author. Film starred Buster Keaton, and apparently the two of them were good friends, so much so that Karen would go on to impersonate Keaton from time to time. In Film, Karen wears extensive aging makeup that makes him look as old as he is now.

What’s an actor to do after he works with Samuel Beckett and Buster Keaton? Why go on to Frankenstein Meets the Space Monster, of course. Then, after working with a young Arnold Schwarzenegger in Hercules in New York, he got into a groove of television appearances, including Starsky and Hutch, Police Woman, McMillan and Wife and The Rockford Files.

Then came what may have been a breakthrough role in All the President’s Men, where he plays Stephen Collins’ lawyer on a television Redford is watching, and also provides (uncredited) the voice of a slippery politician, the one who protests that he’s got “a wife and a kid and a dog and a cat.” He worked with OJ Simpson in 1978’s Capricorn One, and also in 1979’s The China Syndrome. But the first time I noticed him was in Steven Spielberg’s Poltergeist, where he played Craig T. Nelson’s unscrupulous boss. After appearances on Little House on the Prarie and The Paper Chase, he gave what I consider the greatest of his performances in Return of the Living Dead, where he gets to go completely nuts while battling brain-eating zombies in a mortuary. (One of the amusing things about this performance, for me, was that it was in theaters while Karen was also appearing on television as the Pathmark Drugstores spokesman in New York. I couldn’t watch the commercials, where he is paternal, friendly and blithely reassuring, without thinking of him sweating, turning yellow and trying to eat the brains of some teenagers.) He appears in no fewer than three Oliver Stone movies (Wall Street, Nixon and Any Given Sunday) and also in David Lynch’s Mulholland Dr. Bryan Singer directed him in Superman Returns but then cut his scenes. He remains in the titles but does not appear in the movie, bitterly disappointing at least one filmgoer. Finally, he is featured in Will Smith’s upcoming The Pursuit of Happyness.

I don’t know about you, but that’s what I call a career. And it’s not over yet.

The Squid and the Whale

This is a movie about the dissolution of an American family.

I saw it in the theater when it came out. After it was over, I raced home and started writing a script about the dissolution of my own American family, which dissolved when I was roughly the same age as the older son in this movie.

Watched it again tonight. Now I’m thinking, “Nope, I’m not going to finish that script. Because I can’t write as well as this guy.”

This is simply one of the best written, best directed, best acted American films I think I’ve ever seen. It could not be more straightforward, unfussy, unpretentious. It could not be more naturalistic, better observed, unpredictable.

As a director, Noah Baumbach, like Ozu, has one shot. With Ozu it’s the “camera sitting on the floor” shot, with Baumbach its the “handheld camera” shot. A completely stock effect that you would have thought had run out of steam years ago, but it completely disappears here. In Woody Allen’s Husbands and Wives, you’re constantly thinking “Aha, he’s using a jittery, handheld camera to good effect here,” in The Squid and the Whale you don’t even realize that it’s there.

Why don’t you realize it? Probably because the script is so freaking good. Just really extraordinary. Tiny little scenes of completely normal human behavior, tiny little gestures saying volumes about the characters without ever saying “Hey, did you get what that scene was about?” Beginning toward the end of the scene, so that we have to do a little catchup to figure out what’s going on, having the dialogue be things that people are not saying as well as things they are.

Or maybe it’s because the direction and editing are so good. Unselfconscious jump-cuts remove anything that isn’t important, whip-pans look accidental but then turn out to have a narrative or thematic link to the next scene, the camera stays close to faces but never in a way that says “Hey, this is a movie about faces.” Scenes that would have been milked for their “dramatic import” here are presented as they would have been in real life, meaning, one rarely understands when an “important moment” is happening in one’s life. It happens, and many years later one realizes what the important, life-changing, crossroads moment was. No, scene after scene goes by of crushing importance, but it’s all moving too fast and with too much fidelity to life for something as clumsy as “drama” to enter into the picture. That is, it doesn’t feel like you’re watching a scripted drama at all; it feels like a camera crew followed these four characters around for a few months, shot thousands of hours of film, and then edited it down to this.

Or maybe it’s the acting, which is simply some of the best I’ve ever seen. I’ve always liked Jeff Daniels (who would dislike Jeff Daniels?) but his performance here as a faded, past-his-prime novelist and recently-divorced father is just one of the most astonishing I’ve ever seen. And again, not calling attention to itself. Incredibly detailed, thoughtful, lived-in. I can’t remember a movie where I saw people thinking on screen so much. Laura Linney, who’s always good, is equally mesmerizing as the mother. And then there’s the two teenage boys, Jesse Eisenberg and Owen Kline, who give two of the most detailed adolescent performances I’ve ever seen.

For a movie with no “plot” per se, it crackles with intensity and flies by in a breathless (pun intended, you’ll see what I mean) 81 minutes.

This movie is a miracle.

J.S. Bach: The Early Years of Struggle

“Hey, ‘Mr. Counterpoint’ in there, you want to knock it

off already? You’re giving your mother a headache!”

La Bete Humaine

I pop this DVD in the machine, expecting to see a warm, humanist Renoir comedy/drama like Boudu Saved From Drowning, The Rules of the Game or Grand Illusion. Turns out it’s practically a freakin’ Hitchcock movie.

This is a good thing.

A noir before it had a name (1938), La Bete Humaine is a dark tale of lust and murder set amid the railyards of 1930s Paris. Noir, hell: the plot is practically a chapter from Sin City: there’s a good-looking working-class lug who worries that he might actually be a psychotic killer, a mild-mannered middle-management type who is driven to murder by jealousy and a femme fatale who lures men into murdering each other for her, all the while playing the weak, innocent victim.

Because it’s Renoir, of course, things are more complicated than that. As the guy says in Rules of the Game, “Everyone has their reasons.” You never look at the psycho as anything remotely like a monster, the jealous husband is never belittled or scorned and the femme is both plainly manipulative and sadly victimized.

It’s a real pleasure to watch an artist so effortlessly and confidently in command of his tools. The movie is endlessly suspenseful and surprising while never becoming sensational or italicized. It’s Hitchcock without the devices and the remote coldness.

I’m not overly familiar with Zola, but I’m surprised at how pulpy his sense of plot is. I worked on an adaptation of Therese Raquin a while back, and that book not only has lust and murder and intrigue, but also ghosts and hallucinations and an operatic level of dread. I have no idea what the novel of Bete is like but it sounds like it’s just a notch more highbrow than, say, Jim Thompson.

The notes refer to the plot as a “triangle” (between the lug, the femme and the husband), but I detect a fourth player: Lison, the locomotive that the lug (Jean Gabin) works on. Renoir gives the train a full 7-minute wordless introduction as Gabin guides it thundering down the track, through tunnels and into the station. We see that Gabin has an intimate relationship with the engine, which he underscores later on when someone asks him why he doesn’t have a girlfriend. “Oh, I do have a girlfriend,” he says, “Lison.” (Just the fact that he’s given his locomotive a name, much less a woman’s name, says plenty right there.) Later, when he, without preamble, almost strangles a girlfriend to death on an embankment, the only thing that stops him is a train going by: it’s almost as though he’s in a carnal embrace and interrupted by his “wife” entering the room. He breaks off the strangulation and stomps off, guilty and disgusted with himself. Not that he almost killed a woman but because he feels weak and out of control. (Strangest of all, the woman sympathises with him and they walk off together, finishing their date as though nothing had happened [apparently they’d come to that impasse before].) We get the sense that Lison is a stabilizing force in Gabin’s life, that he lavishes all his affection and labor over this locomotive because if he ever stops working, he’ll have no choice but to murder someone. And indeed, once he does finally murder someone, he turns himself in not to the police but to Lison, as though the locomotive is the only one who can judge him.

Screenwriting 101 — The Bad Guy Plot

I’ve worked on a fair number of superhero/fantasy/espionage/sci-fi/what-have-you projects, and the problem is always The Bad Guy Plot. For some reason it’s always the toughest thing in the script to work out.

To work, to be satisfying, to move with grace and wit and a sufficient amount of danger and threat, The Bad Guy Plot must do ALL the following things:

1. The Bad Guy’s story should be explicitly intertwined with that of the protagonist. Ideally, the inciting incident should influence both. The perfect example would be if, say, the chemical explosion that gives a man superpowers also gives The Bad Guy superpowers but also a severe deformity, making it so that he cannot lead a normal life and thus turns Bad.

2. The Bad Guy’s desire cannot be simply the destruction of the protagonist. The Bad Guy has to have some other goal that has nothing to do with the protagonist (except in the broadest societal sense, ie the hero’s obligation to right wrongs) but which the protagonist must stop. Like, say, most of the James Bond films.

3. The Bad Guy and the protagonist must interact often and throughout the narrative. This is a whole lot harder than it sounds. If the Bad Guy is involved in something Bad and it’s the protagonist’s job to stop him, what usually happens is that the Bad Guy does the Bad Thing in private while the protagonist looks for the Bad Guy, and then there’s a confrontation in Act III.

4. Hardest of all, the Bad Guy’s plan must make sense and follow a logical progression, not only through the narrative but beyond. That is to say, the writer must stop and think "Okay, let’s say Lex Luthor succeeds in growing his new continent and drowning half the world’s population: then what?" This is what I call the "Monday Morning" question. In Mission:Impossible 2, terrorists plan to take over a pharmaceutical company, release a plague, then sell the world the cure. And I’m sitting in the theater thinking "And on Monday Morning, when the pharmaceutical company’s stockholders find out that 51 percent of the corporation is now owned by a terrorist organization, thenwhat?" When Dr. Octopus succeeds in building a working model of his fusion whatsit on the abandoned pier in the East River, after robbing a bank, wrecking a train destroying a number of buildings and endangering the lives of thousands of people, then what?

Keeping all of this in mind, what are your favorite Bad Guy Plots? Which ones have a plot that intertwines with the protagonist’s plot, has a goal that the protagonist, and only the protagonist, can stop, keeps the Bad Guy and the protagonist interacting throughout, and — gasp — makes sense?

I’ll start: Superman II.