Some thoughts on the screenplay for Oppenheimer

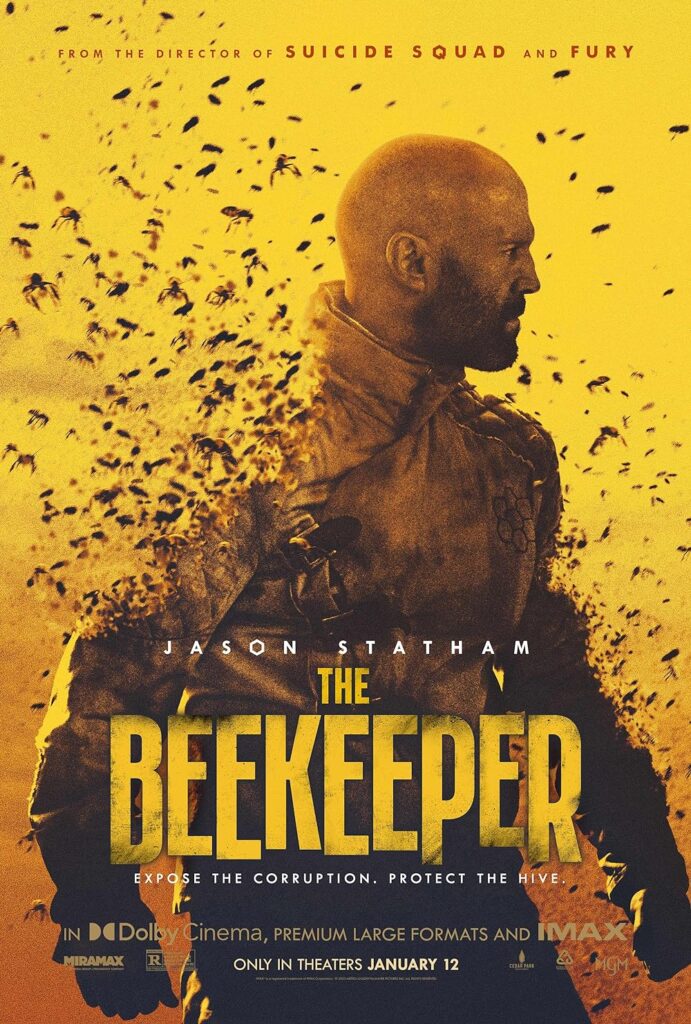

The Beekeeper

When I was in my 20s I managed a movie theater on 59th St in New York, the Manhattan Twin. It was part part of the City Cinemas chain, which was a clutch of theaters that had been built on the ruins of Dan Rugoff’s bankrupt Cinema 5 theater chain. City Cinemas’ flagship theater, Cinema I, was right around the corner from the Manhattan Twin, but the difference in programming could not have been different. Cinema I would show a movie like Kiss of the Spider Woman or And the Ship Sails On, while the Manhattan Twin would show movies like Police Academy or Splash. As I used to put it, “Cinema I is across the street from Bloomingdale’s, the Manhattan Twin is across the street from a deli called Meat Land.”

When I was in my 20s I managed a movie theater on 59th St in New York, the Manhattan Twin. It was part part of the City Cinemas chain, which was a clutch of theaters that had been built on the ruins of Dan Rugoff’s bankrupt Cinema 5 theater chain. City Cinemas’ flagship theater, Cinema I, was right around the corner from the Manhattan Twin, but the difference in programming could not have been different. Cinema I would show a movie like Kiss of the Spider Woman or And the Ship Sails On, while the Manhattan Twin would show movies like Police Academy or Splash. As I used to put it, “Cinema I is across the street from Bloomingdale’s, the Manhattan Twin is across the street from a deli called Meat Land.”

In the fall of 1984, the Manhattan Twin booked a Charles Bronson vehicle titled The Evil That Men Do. As the manager, it was my responsibility to watch every movie we showed, to make sure the reels were in the right order and the print was presentable. I watched The Evil That Men Do and I didn’t like it. I found it unnecessarily crass, vulgar and cheap, and its violence overly harsh and brutal. I expected it to die a quick death and be replaced on our screen by, maybe, the delightful Steve Martin/Lily Tomlin comedy All of Me.

But The Evil That Men Do didn’t bomb. It wasn’t a huge hit, but it didn’t bomb. The theater was never full, the theater was never even half-full, but the audience came, and it kept showing up. Every time we thought the box office for the picture was going to trail off, it would rally again, never enough to be a smash hit, but enough to keep it in the theater for another week. The movie had legs. Stumpy legs, to be sure, but solid, and they kept moving forward every week. The audience never dropped off, it just remained static, week after week. It opened on September 21 and we were still showing it on Thanksgiving, which turned out to be twice the movie-going day anyone in the theater chain expected it to be. We were short-staffed, because it was Thanksgiving, and we were besieged by hundreds of people all day on our two screens.

I remember, on that long Thanksgiving Day, wondering “Who are these people?” The Evil That Men Do was, at that point, in its ninth week, and here we were, packing them in on a day when everyone should have been at home with their families.

So I watched them as they came out of the movie. They were all older men, men in their late 40s, 50s, early 60s. They never had dates, they always came alone. They were paunchy and saggy, their faces lined and their eyes flinty. They were tired, worn, and dyspeptic. They were working class, dressed in windbreakers and overcoats, with sweaters or sweatshirts over button-down shirts. They were the kind of men I had never thought about for a single second of my life, cab drivers and factory workers, middle-managers and plumbers, shoe salesmen and tradesmen. And they all wanted to see Charles Bronson in The Evil That Men Do.

I don’t remember a single second of The Evil That Men Do, but I can tell you, without looking, what it’s about: a middle-aged assassin is brought out of retirement because a close friend of his has been killed, and he will stop at nothing to murder all the people responsible.

And I thought, well, I don’t like that movie, and I don’t buy that kind of macho bullshit fantasy, but look at the faces of these men walking out of the theater. They love the movie, and they have found something of value in it, and it has made them feel, for a couple of hours, less alone in the world.

Like the Grinch on Christmas Eve, my heart grew three sizes that day, and I became much more forgiving of movies I don’t like. I realized that, while they were not to my taste, that that was okay, because not everything has to be made for me. What is required is that a movie find its audience and give it what it wants.

After that, I started to watch everything we showed, in the theater, with an audience. It didn’t matter what it was, a teen comedy, a romance, a horror movie, if an audience responded to it I wanted to know why. I tossed aside whatever personal preferences I had and paid attention to what the audience was looking for, and spent a lot of time wondering why one movie bombed and another one flourished. I now remember movies from that era as much for their audience’s reactions as for the movies themselves.

The decades flew by, but every once in a while I would stop and think about The Evil That Men Do and the mysterious audience of middle-aged working-class men who turned up, week after week, to watch it, and the bond that a movie creates with its audience, regardless of the quality of the product.

I realized the men who came to see The Evil That Men Do probably felt as though they had all followed the rules set down by the Truman administration: get a job, get married, have kids, buy a house, pay your mortgage, die happy. But life hadn’t turned out that way for them. They all felt shortchanged. They all felt like they had been forgotten. Their kids had moved out, their wives perhaps as well, and they didn’t have a house, they were renting now, and their dwellings were getting smaller and smaller as Reagan’s economy handed more and more of their savings over to plutocrats. And every day, more was being taken from them, just through the process of getting old.

That audience needed a hero. They needed to see a man who was both incorruptible and indestructible, highly intelligent and and expert in both strategic and tactical maneuvers. They wanted to see a man of the highest possible moral character, a man who had been around the world and seen a lot of trouble but who now wants only to live his life in peace, who wants only the leisure to putter around his country house and engage in some kind of hobby — stamp collecting, maybe, or refurbishing a vintage sports car, or building elaborate dioramas of Civil War battles. This man would only want a quiet life where they were free to contemplate the endless tapestry of life’s mysteries, but he would also, secretly, be an unstoppable killing machine who is prepared to exact bloody revenge when he is pushed too far. This hero would talk as little as possible, his primary expression would be through motion, and any dialogue he had should be honed and polished into monosyllabic gems.

That audience was prepared to forgive a movie any amount of ludicrous plot, any number of outrageous contrivances, any display of improbable physics, as long as their stoic, had-enough hero hit his beats, dispensed unadulterated justice, and lived to fight another day.

Anyway, here we are, and it turns out I’m now one of those guys, and I thoroughly enjoyed the completely ridiculous The Beekeeper.